Primers • Retrieval Augmented Generation

- Overview

- Motivation

- The Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) Pipeline

- Advantages of RAG

- Ensemble of RAG

- Choosing a Vector DB using a Feature Matrix

- Building a RAG pipeline

- Ingestion

- Retrieval

- Lexical Retrieval

- Semantic Retrieval

- Hybrid Retrieval (Lexical + Semantic)

- Metadata filtering

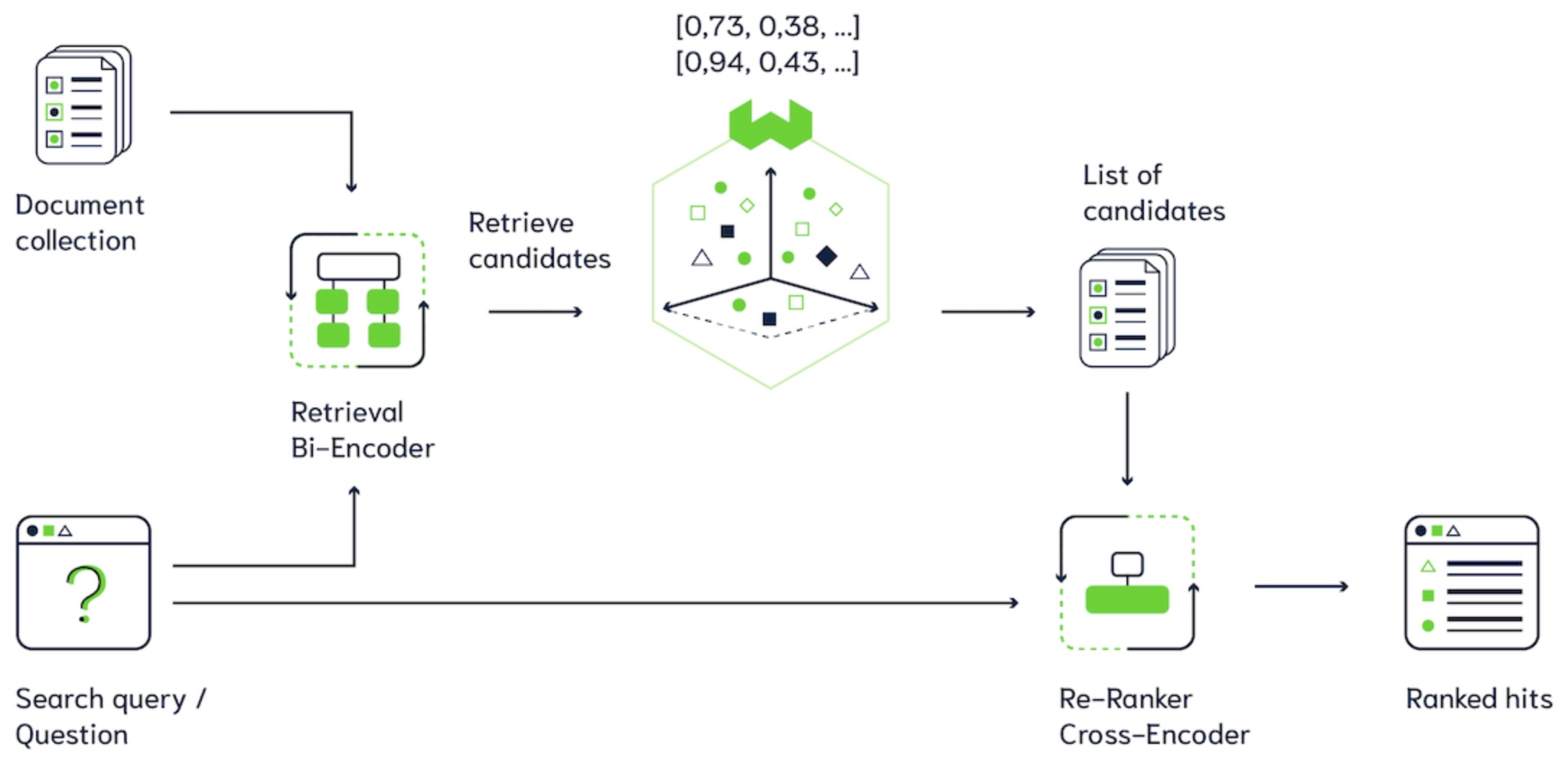

- Re-ranking

- Re-ranking in multistage retrieval pipelines

- Classes of semantic re-ranking models

- Learning-to-Rank paradigms

- Neural re-rankers

- Instruction-Following Re-ranking

- Metadata-Based Re-rankers

- Response Generation / Synthesis

- RAG in Multi-Turn Chatbots: Embedding Queries for Retrieval

- End-to-End Flow

- Component-Wise Evaluation

- Multimodal Input Handling

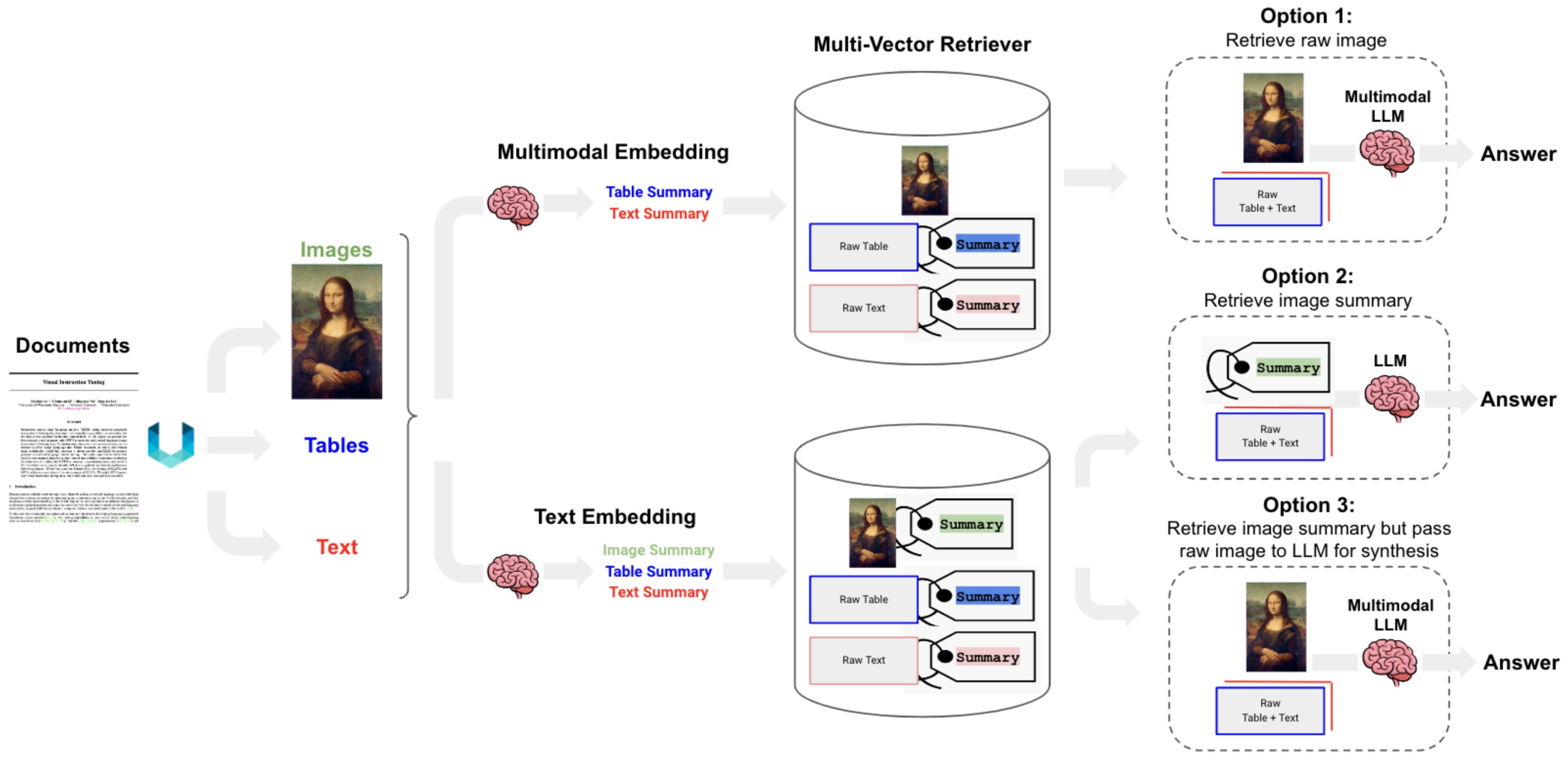

- Multimodal RAG

- Multi-Hop RAG

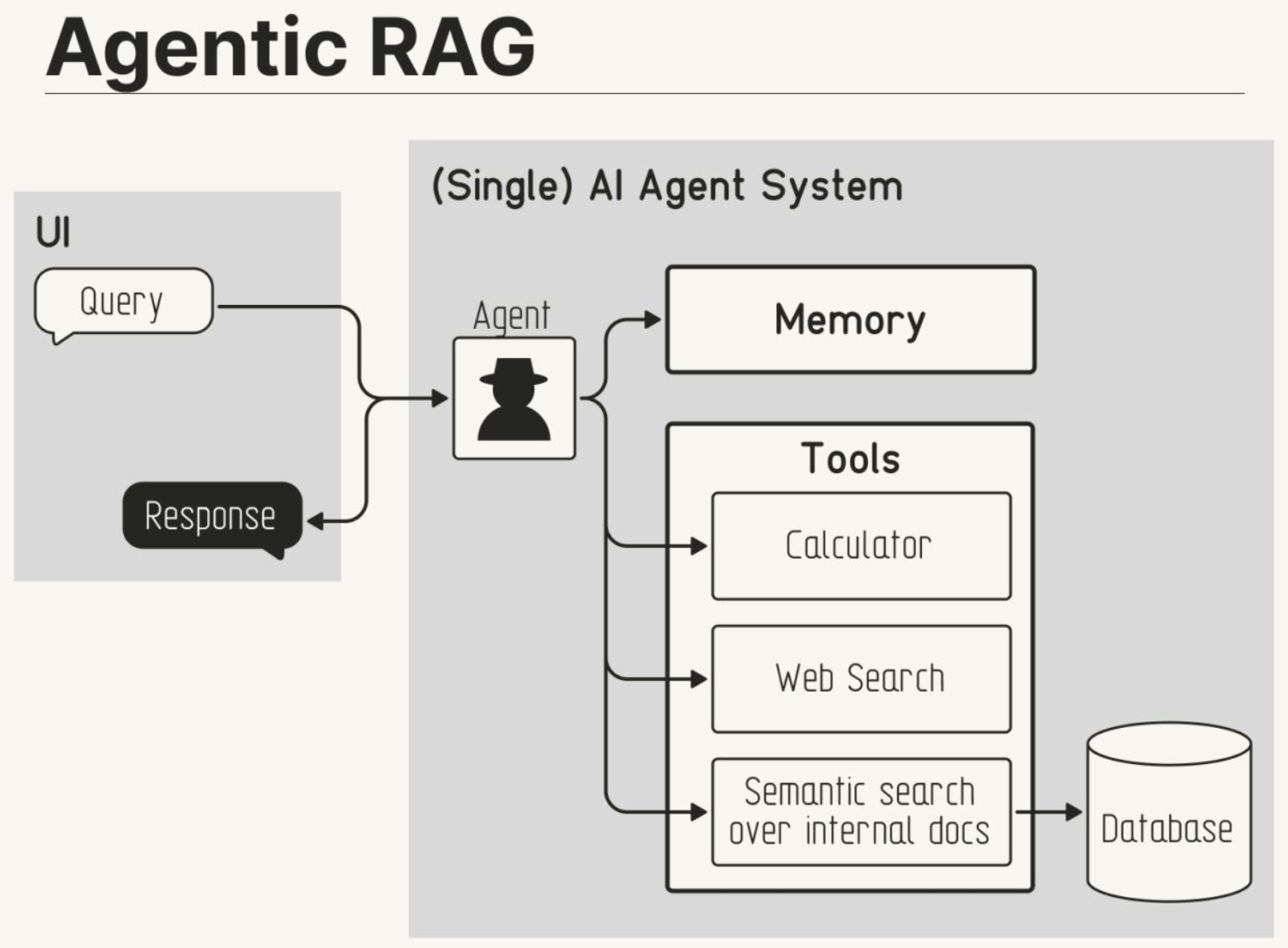

- Agentic RAG

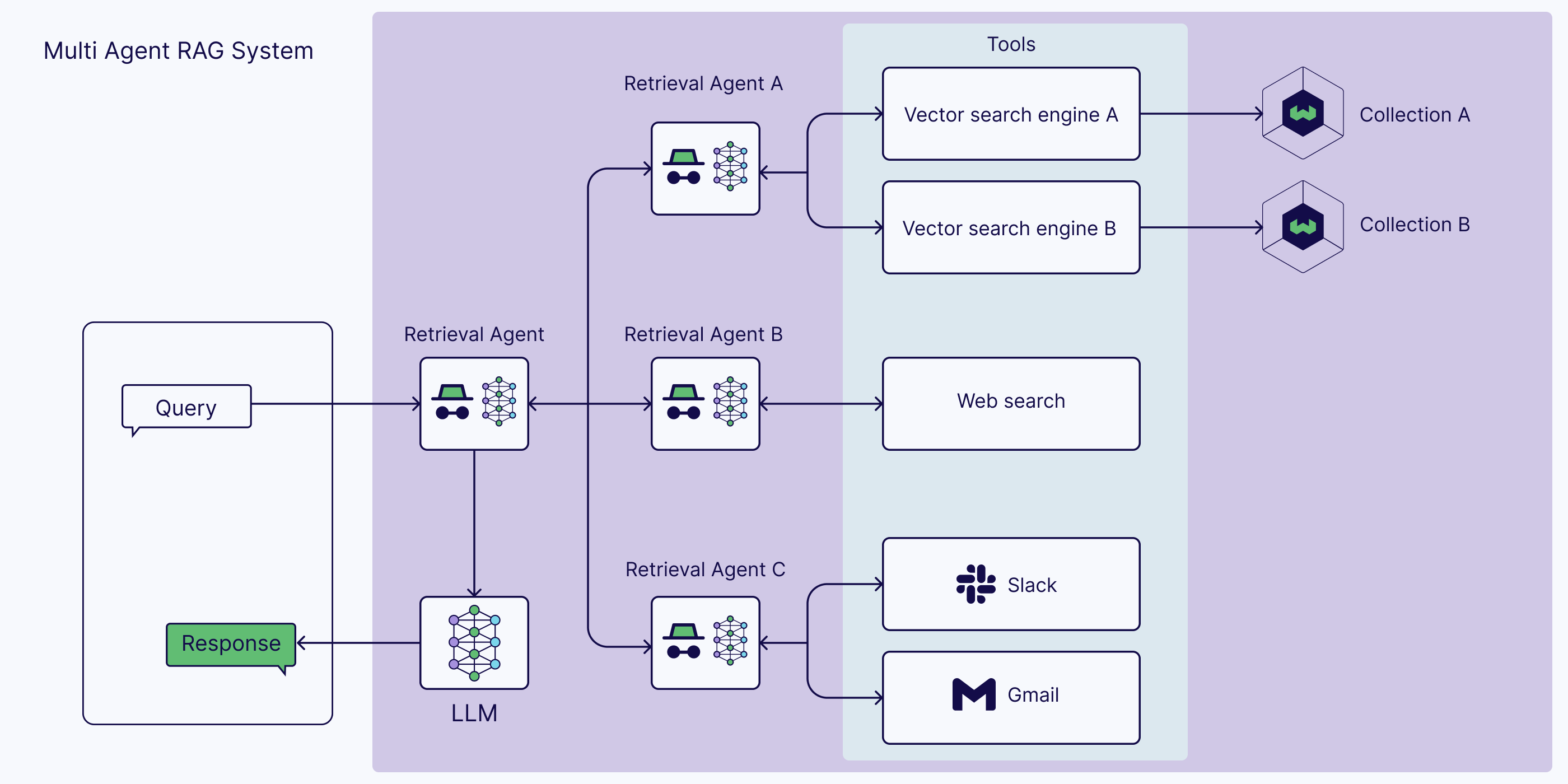

- Overview

- Agentic Decision-Making in Retrieval

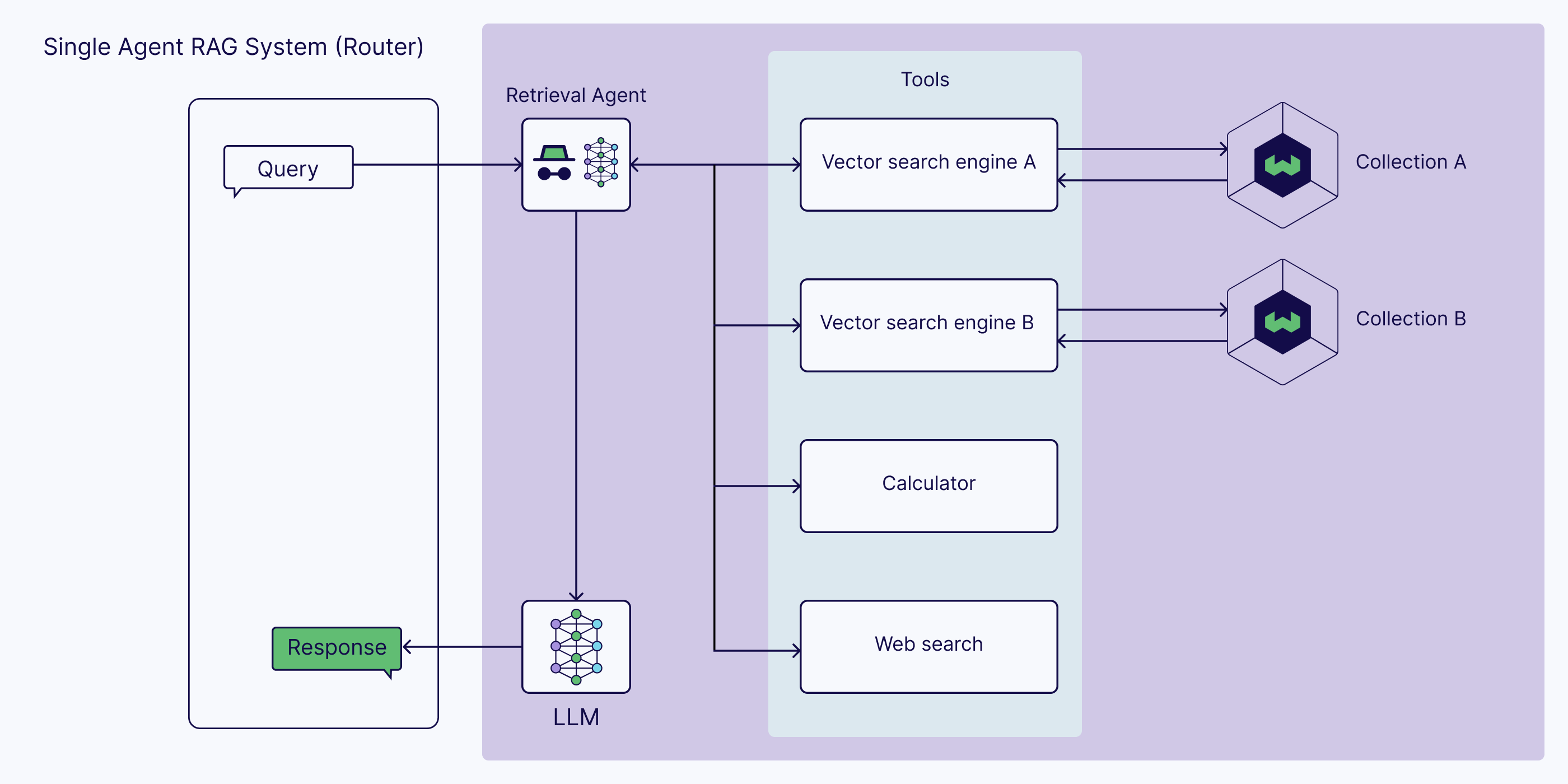

- Agentic RAG Architectures: Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent Systems

- Beyond Retrieval: Expanding Agentic RAG’s Capabilities

- Agentic RAG vs. Vanilla RAG

- Implementation

- Use-cases

- Advantages

- Limitations

- Code

- Disadvantages

- Sample Prompt

- Hierarchical RAG

- RAG vs. Long Context Windows

- Improving RAG Systems

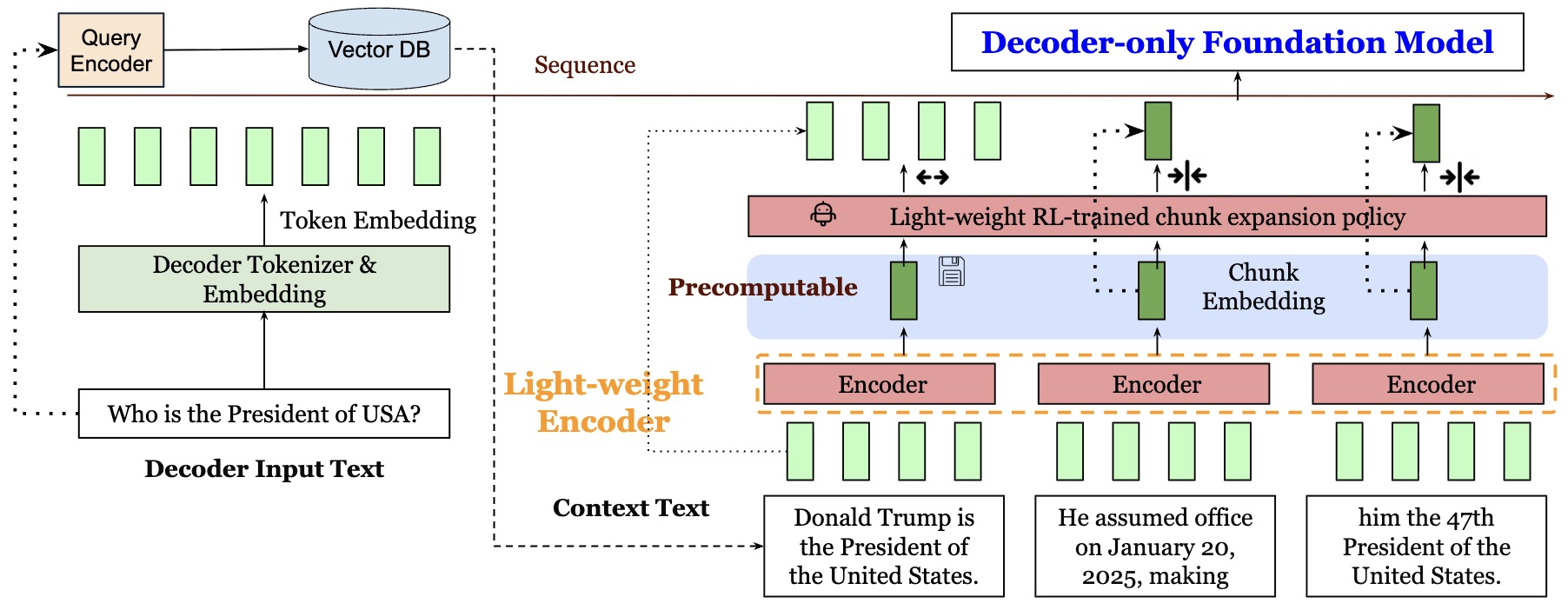

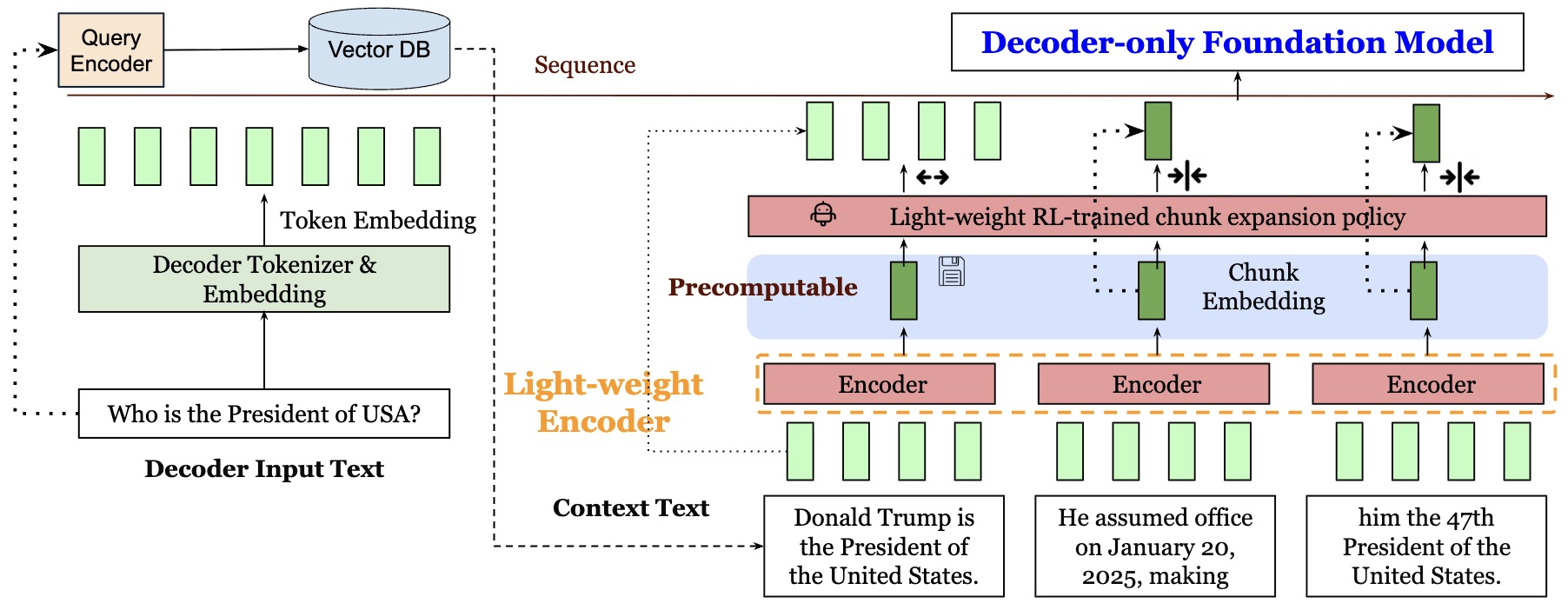

- RAG 2.0

- RAG Benchmarks

- Selected Papers

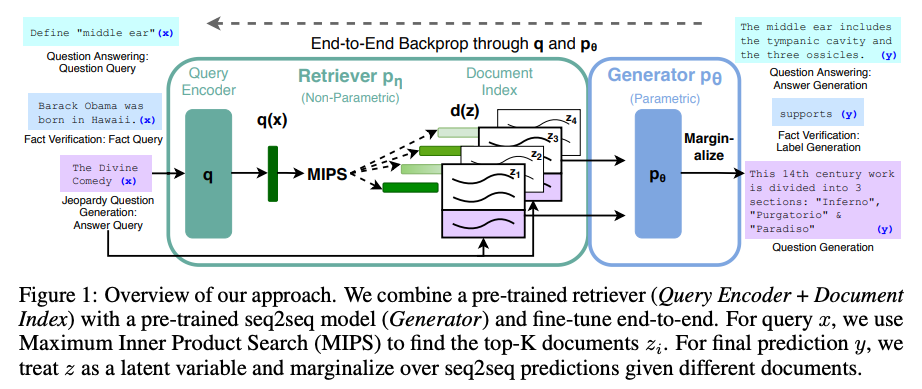

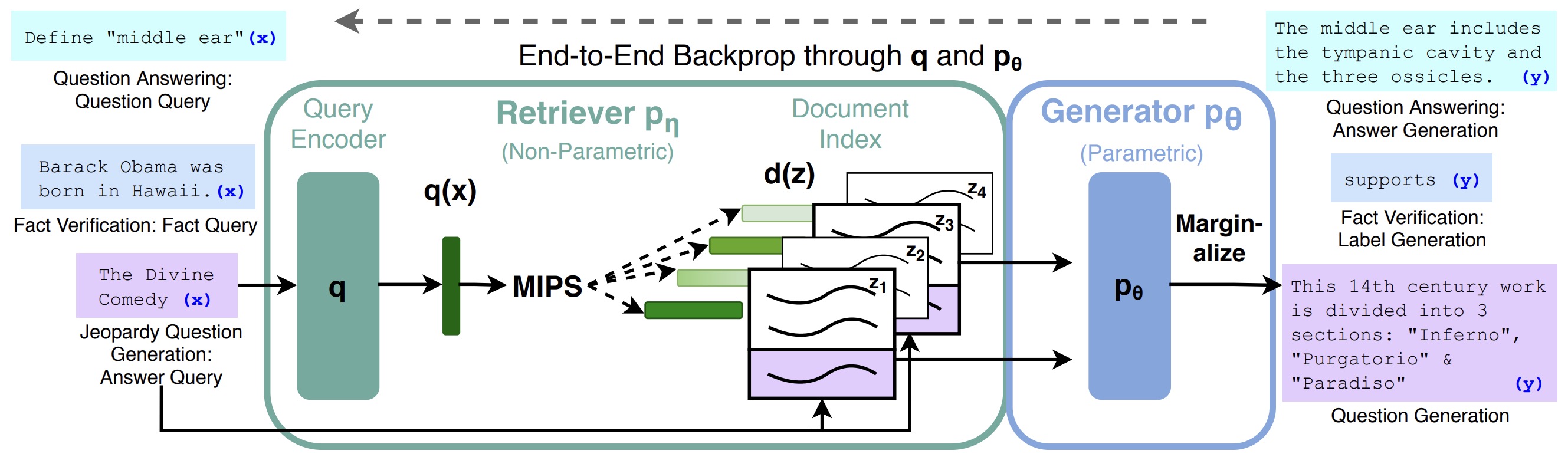

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks

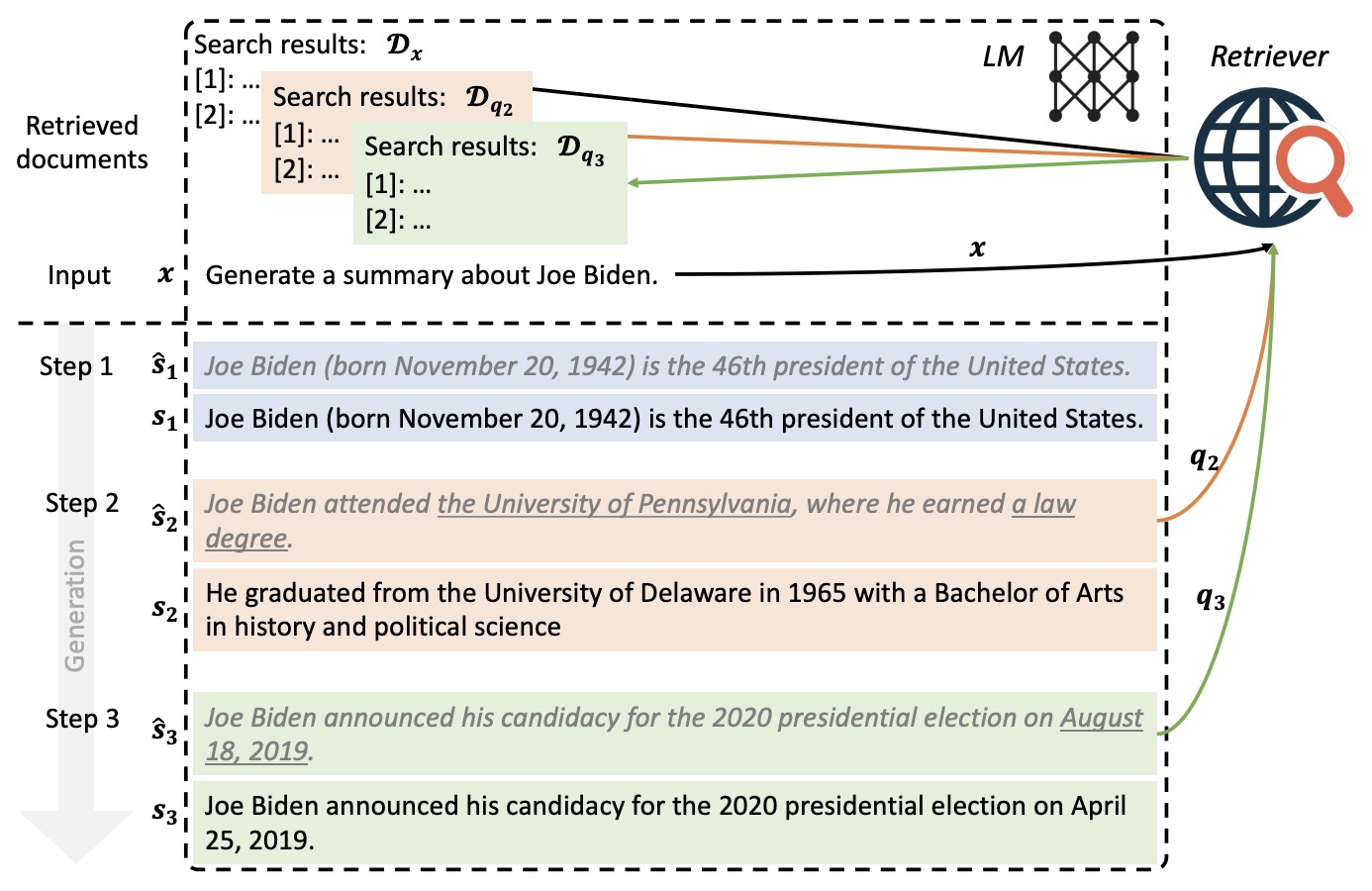

- Active Retrieval Augmented Generation

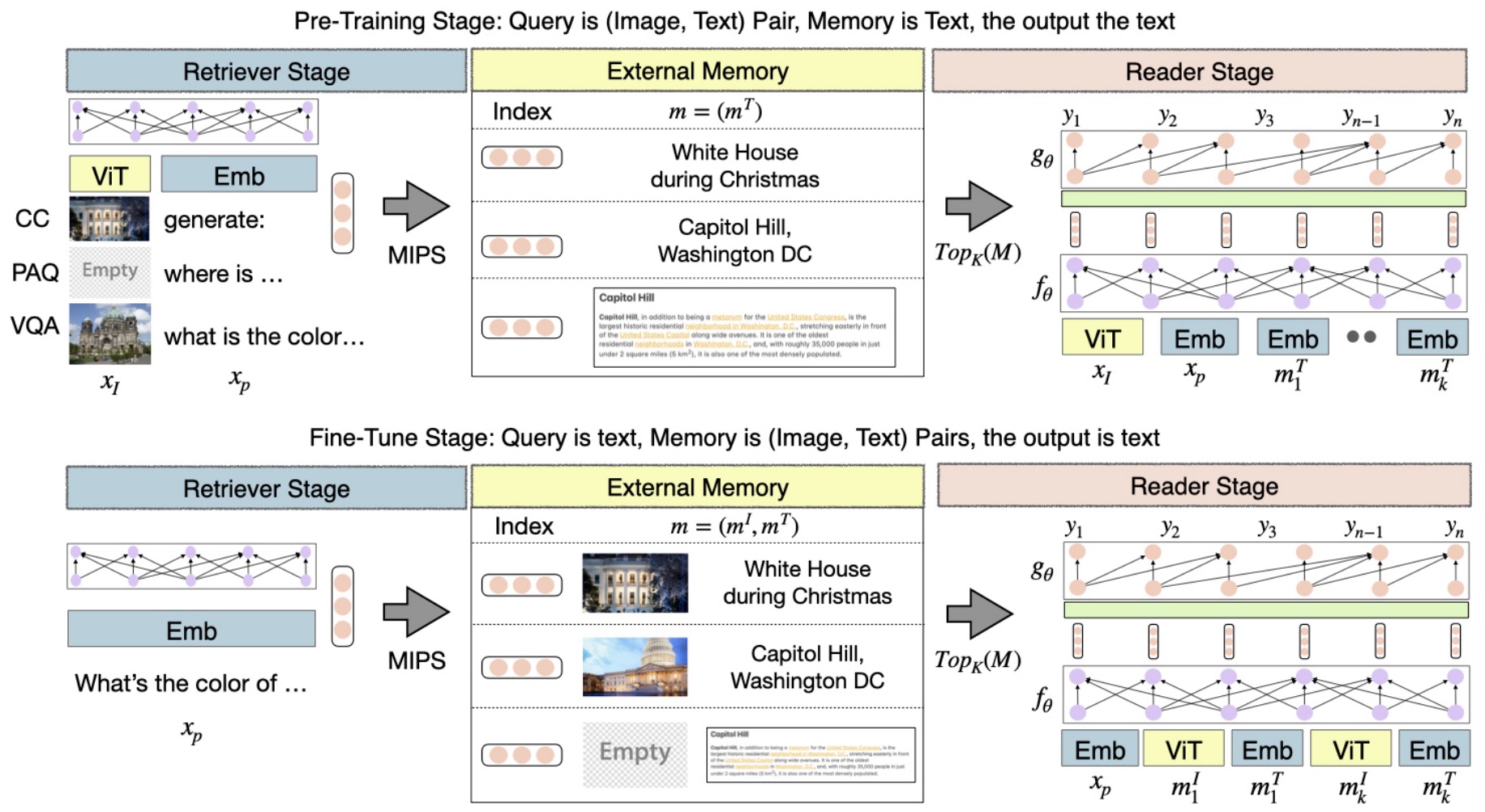

- MuRAG: Multimodal Retrieval-Augmented Generator

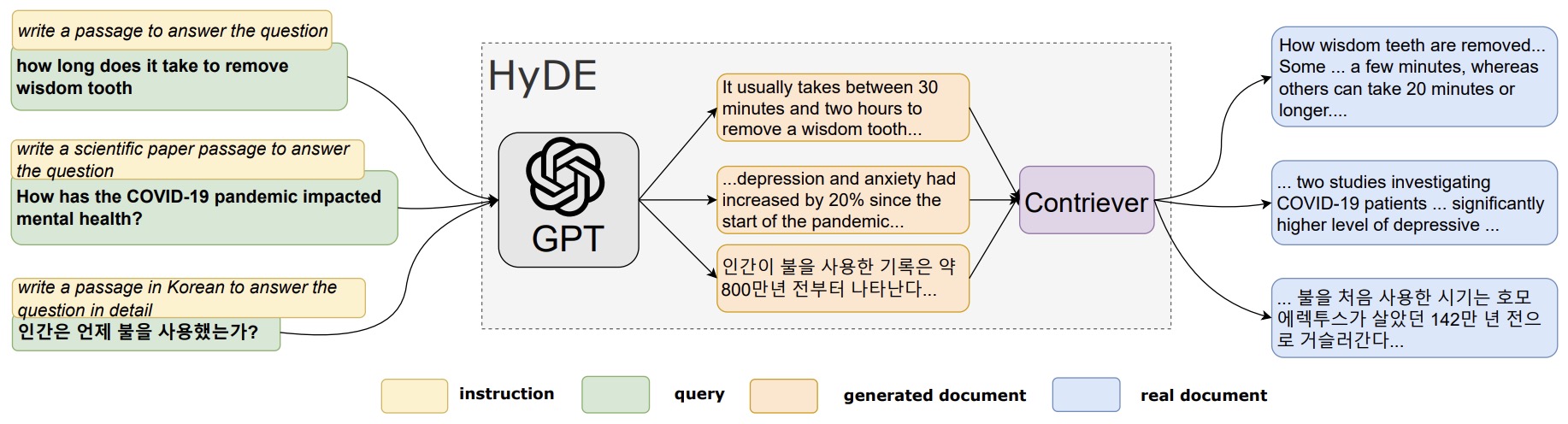

- Hypothetical Document Embeddings (HyDE)

- RAGAS: Automated Evaluation of Retrieval Augmented Generation

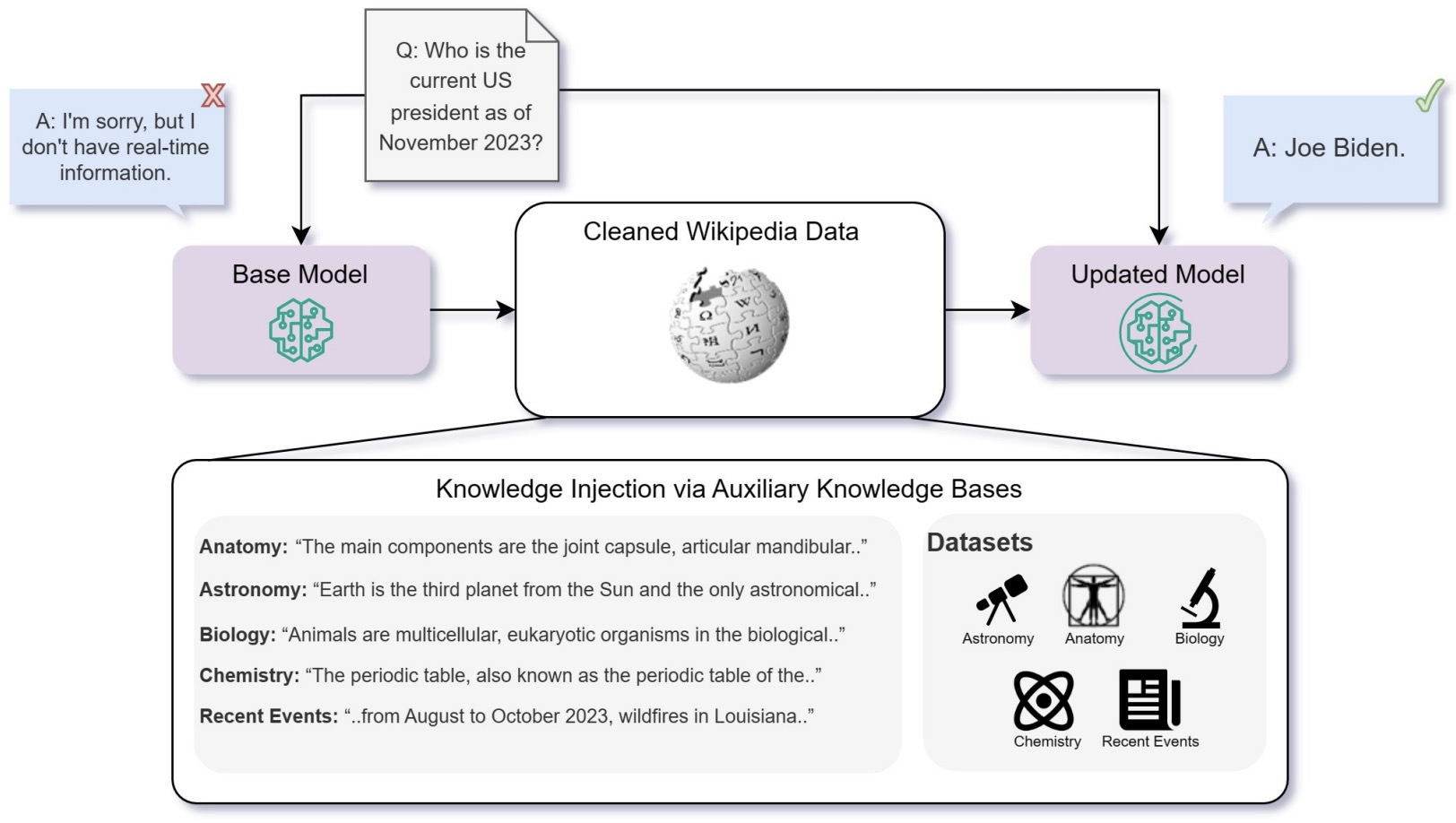

- Fine-Tuning or Retrieval? Comparing Knowledge Injection in LLMs

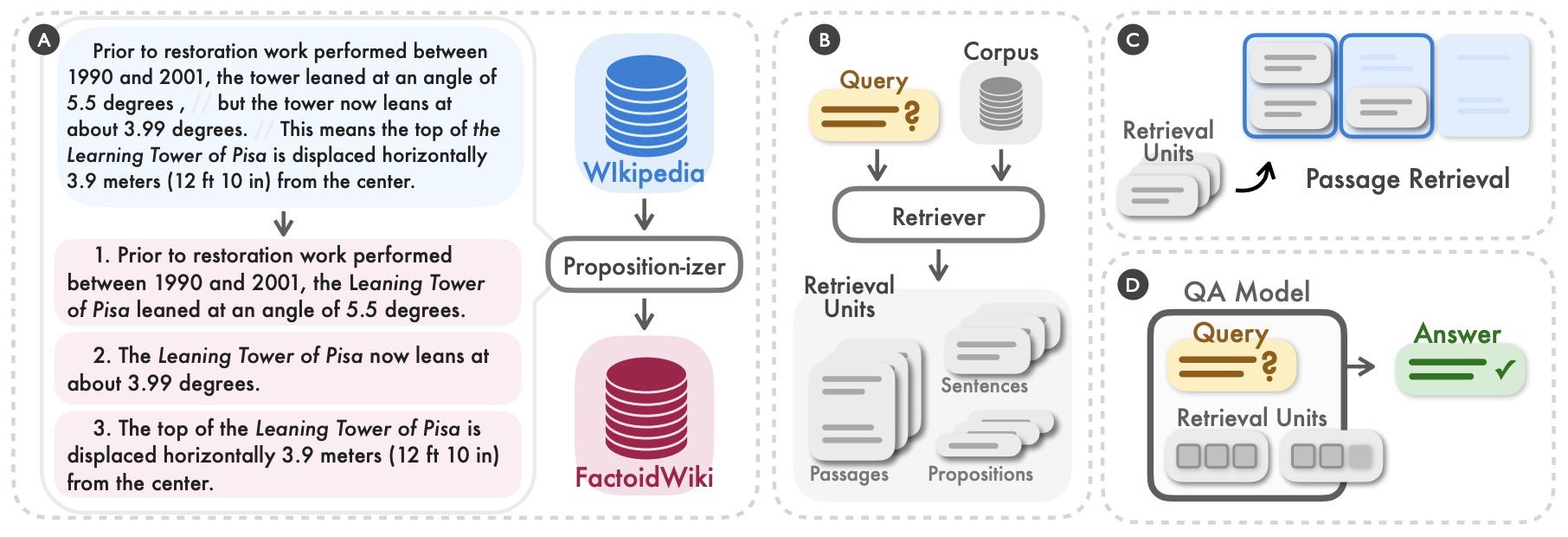

- Dense X Retrieval: What Retrieval Granularity Should We Use?

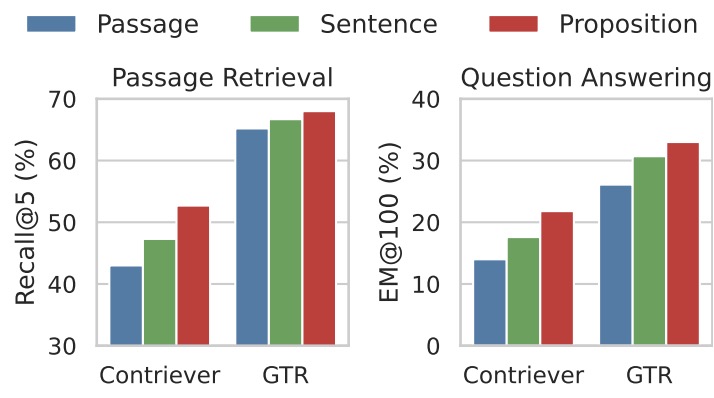

- ARES: An Automated Evaluation Framework for Retrieval-Augmented Generation Systems

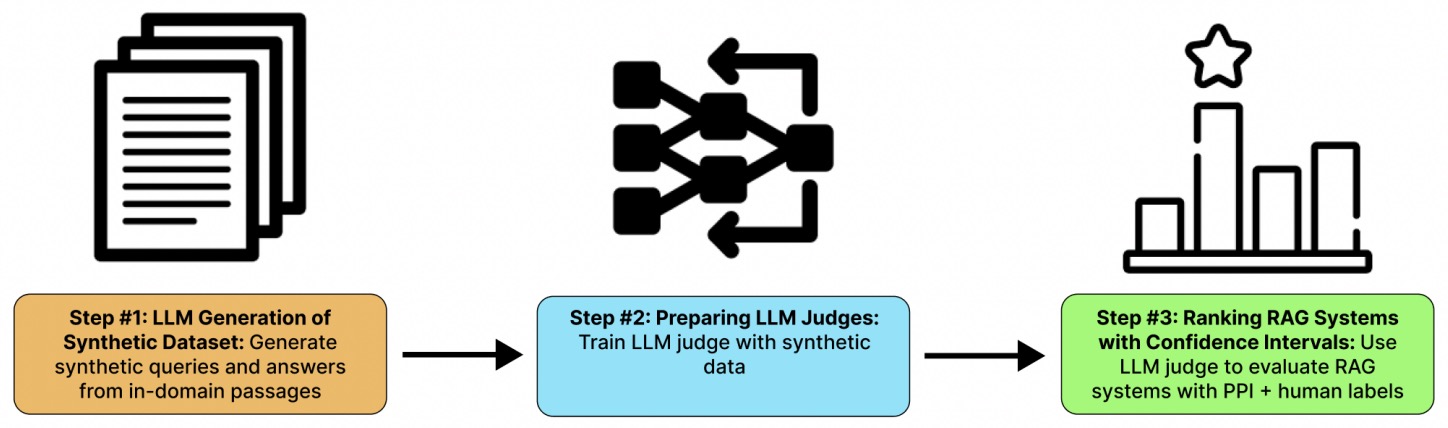

- Seven Failure Points When Engineering a Retrieval Augmented Generation System

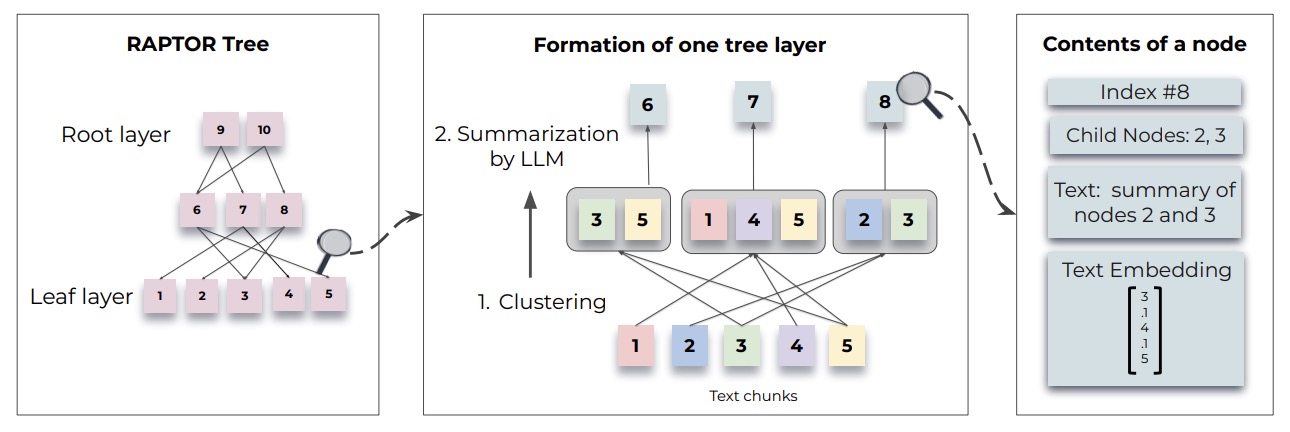

- RAPTOR: Recursive Abstractive Processing for Tree-Organized Retrieval

- The Power of Noise: Redefining Retrieval for RAG Systems

- MultiHop-RAG: Benchmarking Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Multi-Hop Queries

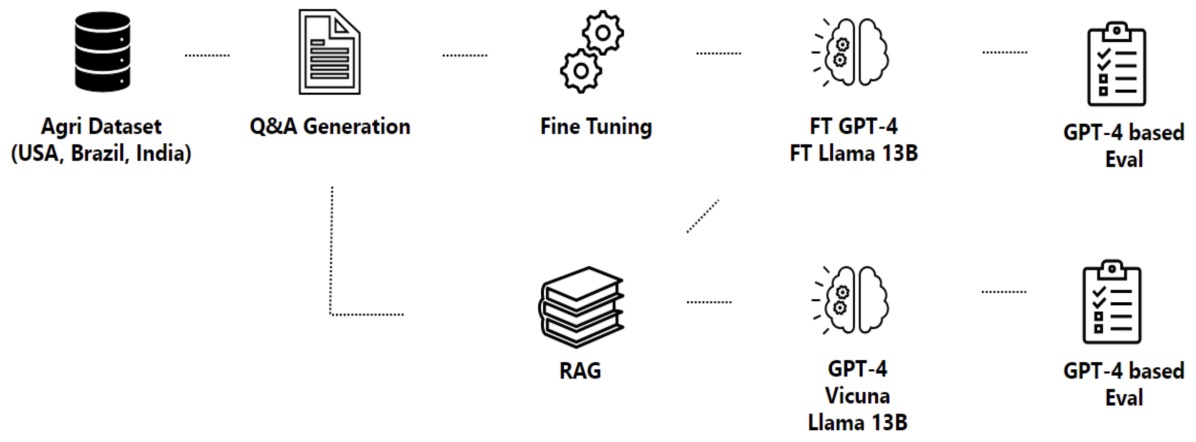

- RAG vs. Fine-tuning: Pipelines, Tradeoffs, and a Case Study on Agriculture

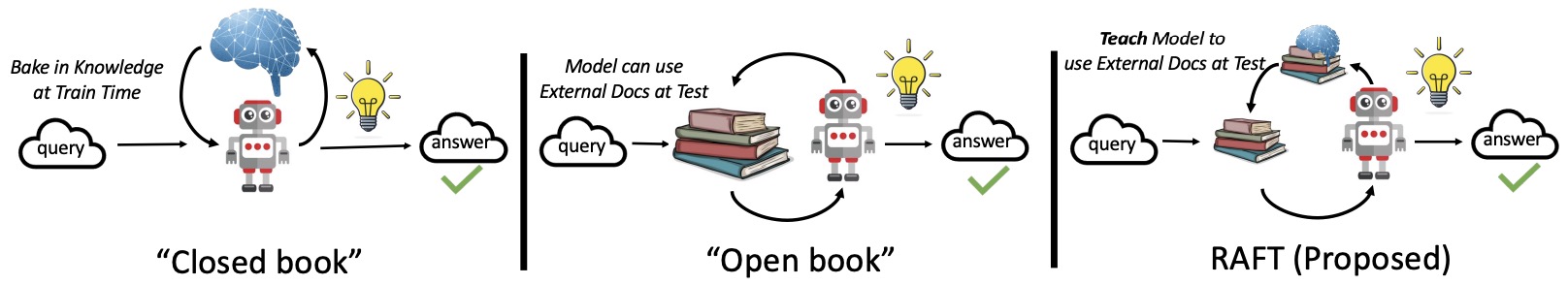

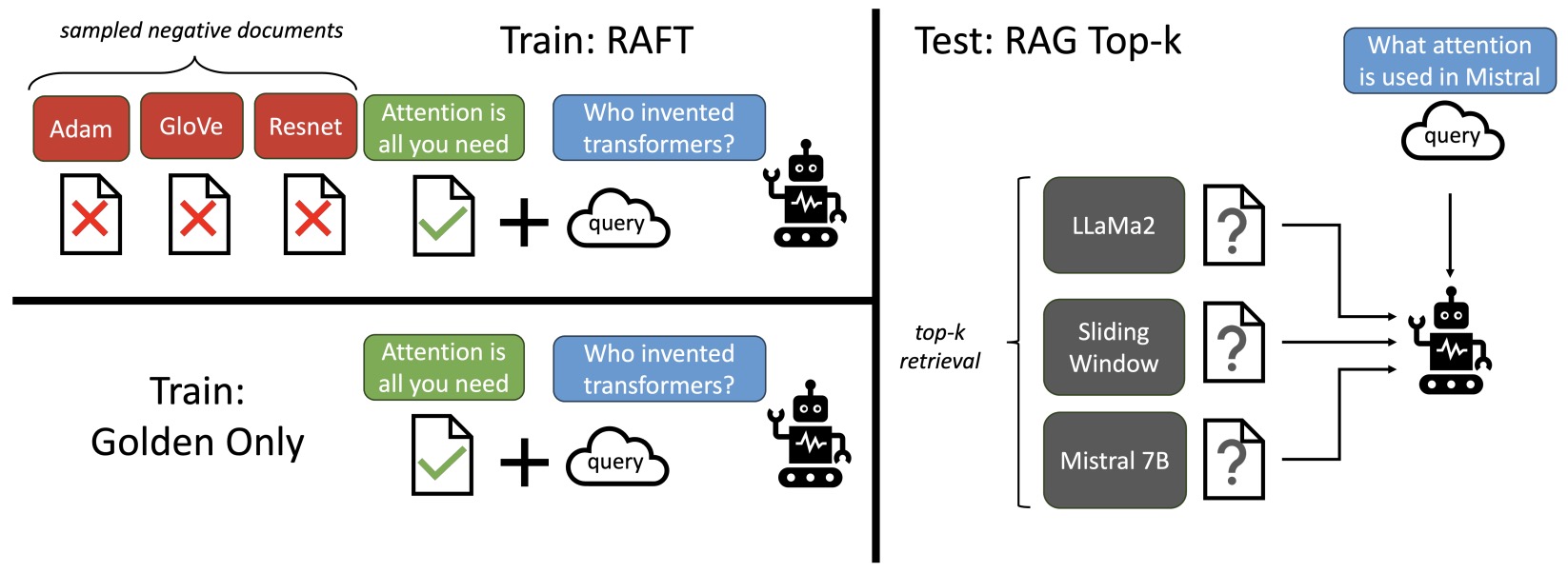

- RAFT: Adapting Language Model to Domain Specific RAG

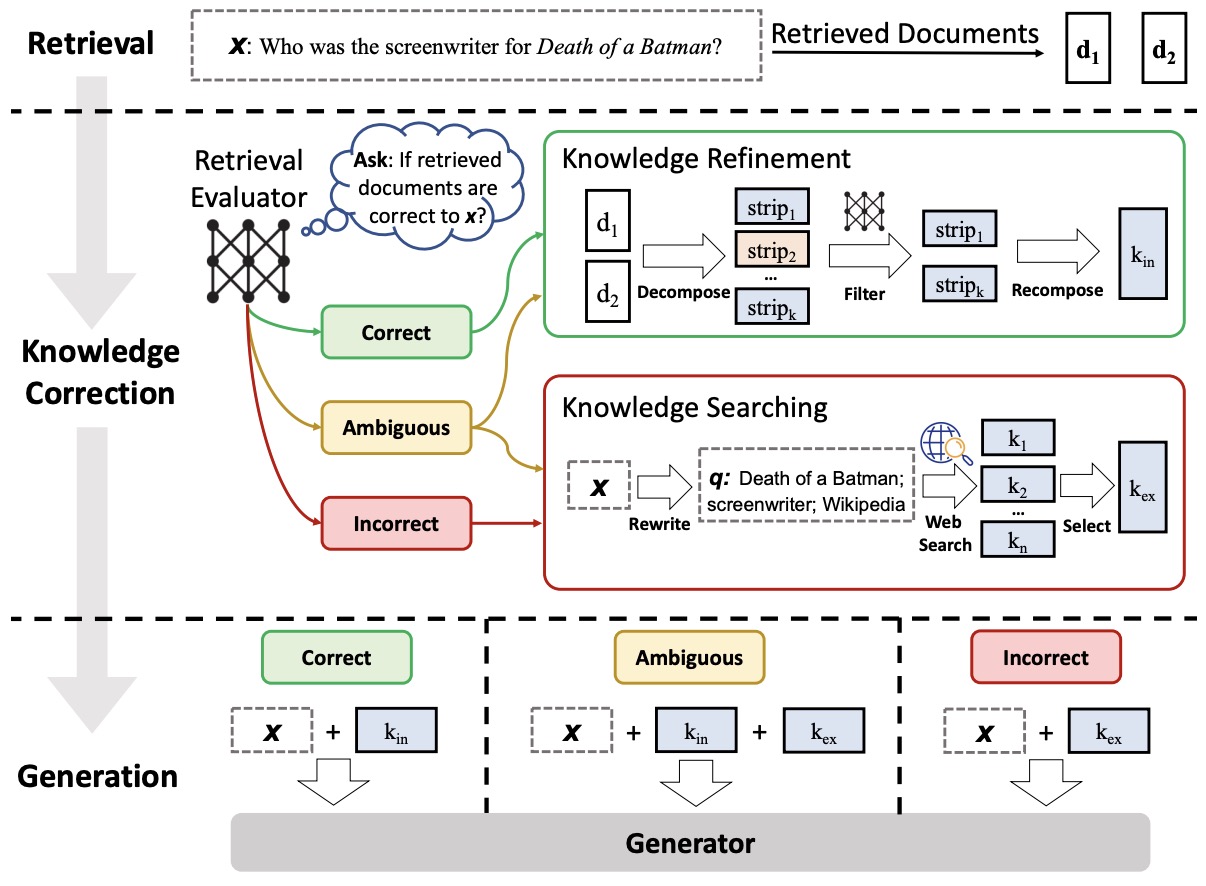

- Corrective Retrieval Augmented Generation

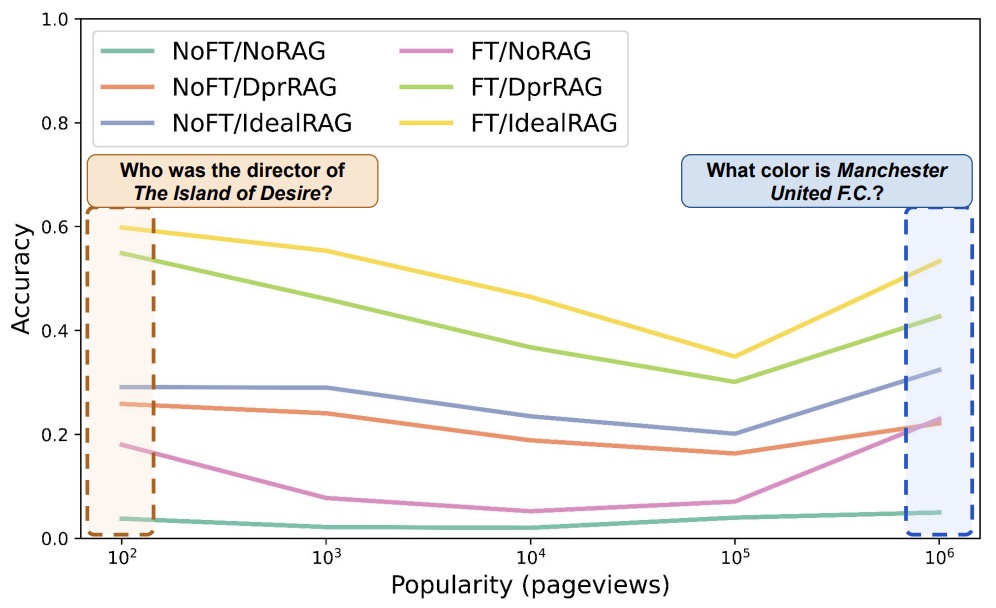

- Fine Tuning vs. Retrieval Augmented Generation for Less Popular Knowledge

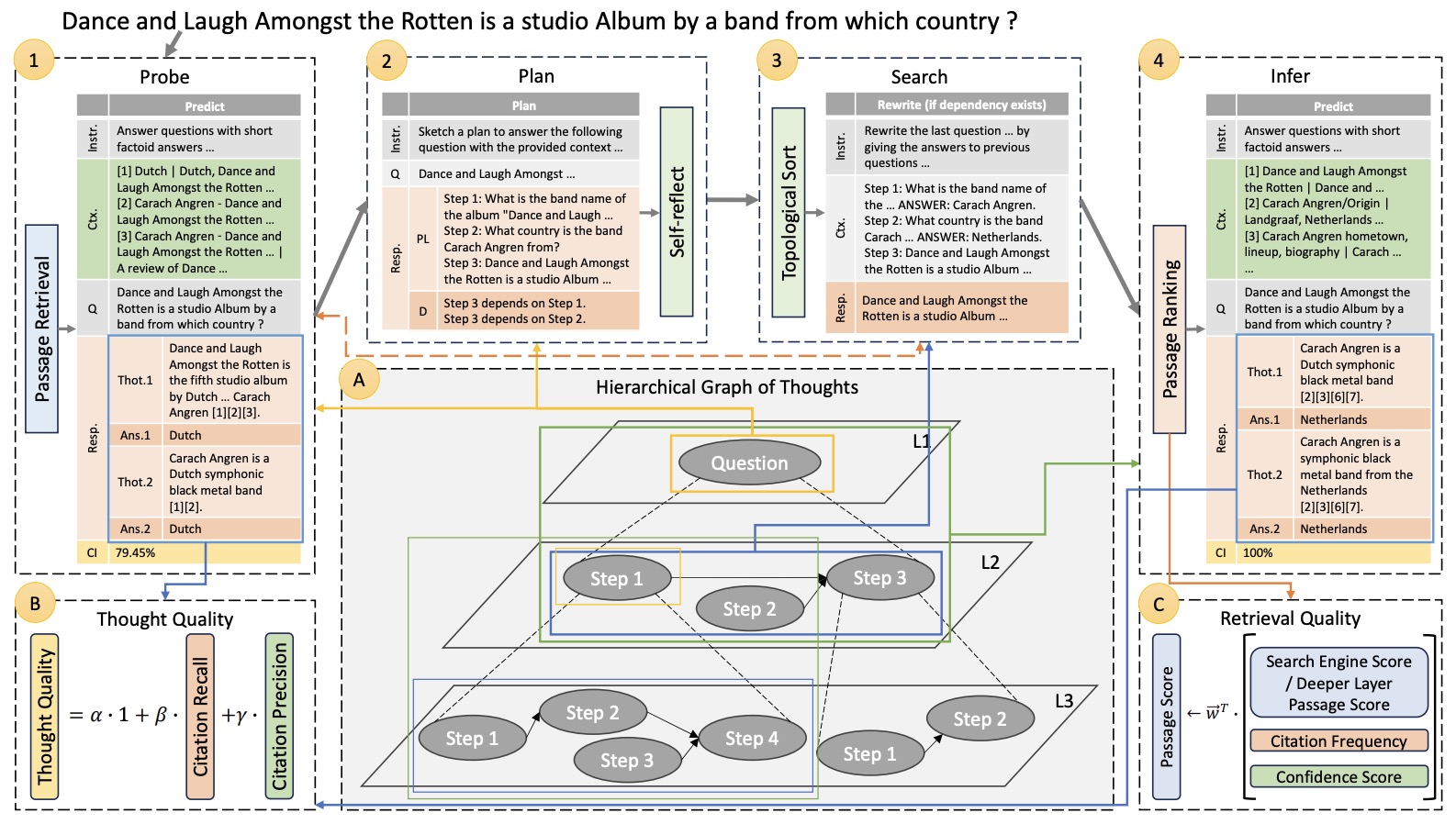

- HGOT: Hierarchical Graph of Thoughts for Retrieval-Augmented In-Context Learning in Factuality Evaluation

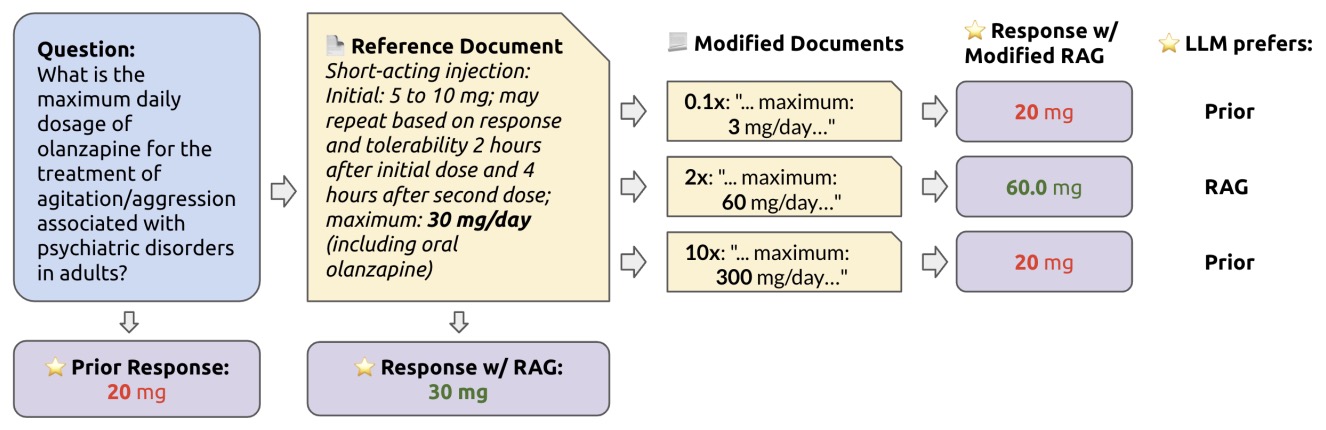

- How faithful are RAG models? Quantifying the tug-of-war between RAG and LLMs’ internal prior

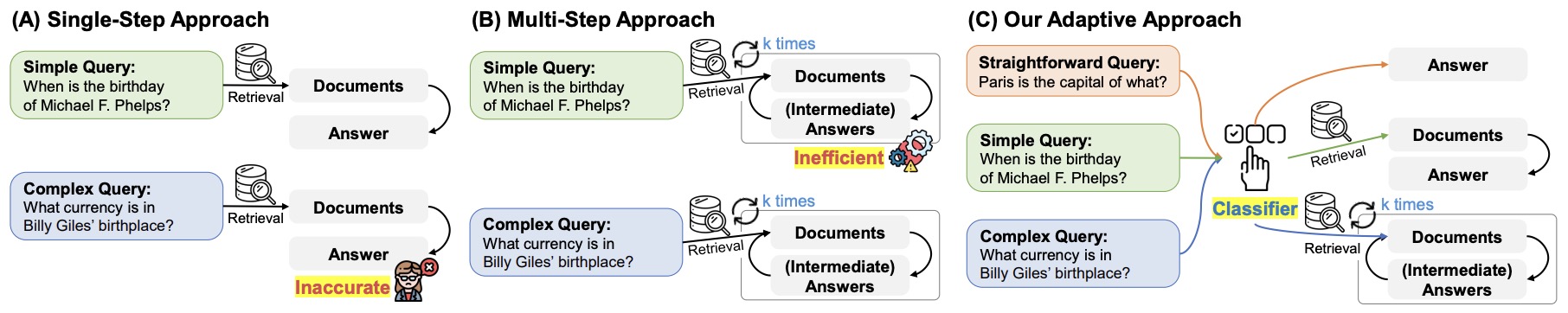

- Adaptive-RAG: Learning to Adapt Retrieval-Augmented Large Language Models through Question Complexity

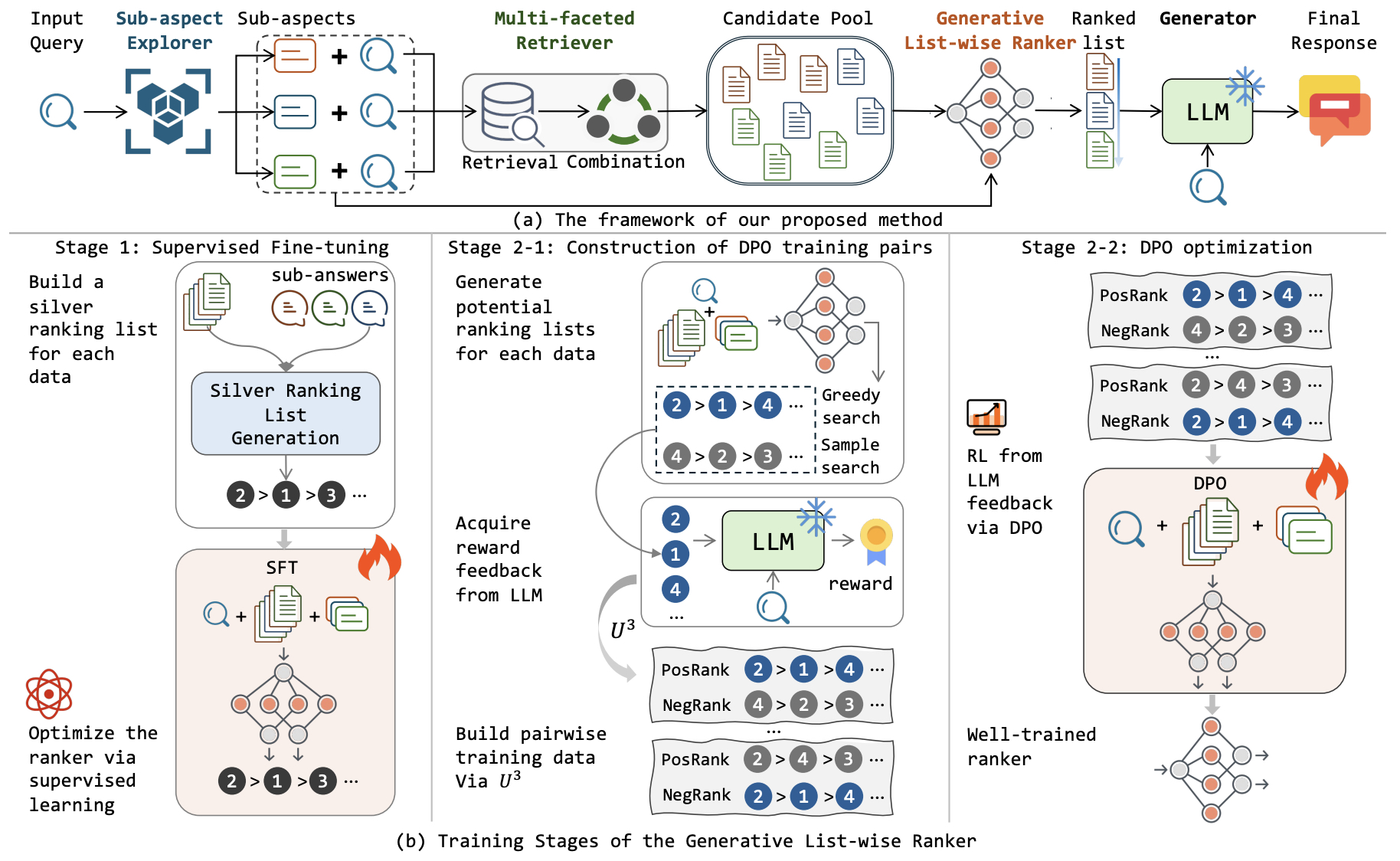

- RichRAG: Crafting Rich Responses for Multi-faceted Queries in Retrieval-Augmented Generation

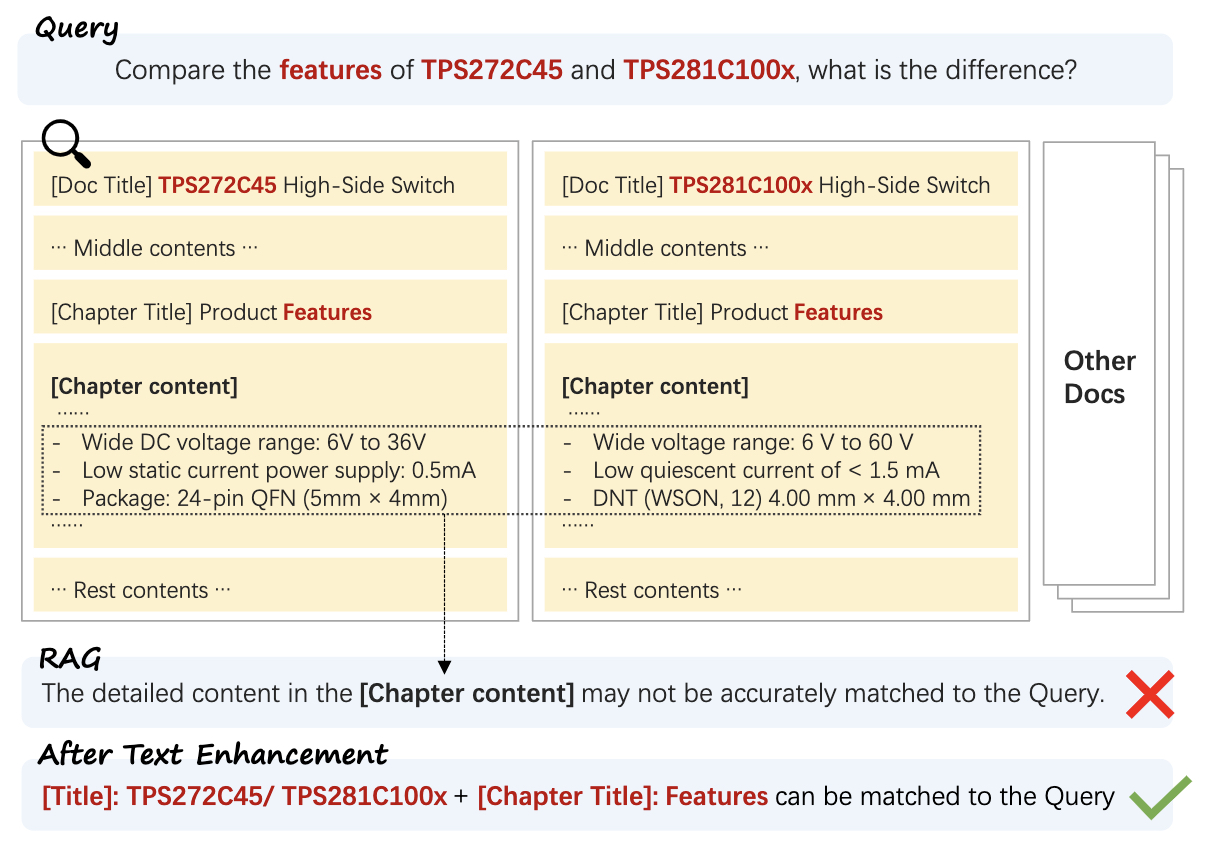

- HiQA: A Hierarchical Contextual Augmentation RAG for Massive Documents QA

- REFRAG: Rethinking RAG based Decoding

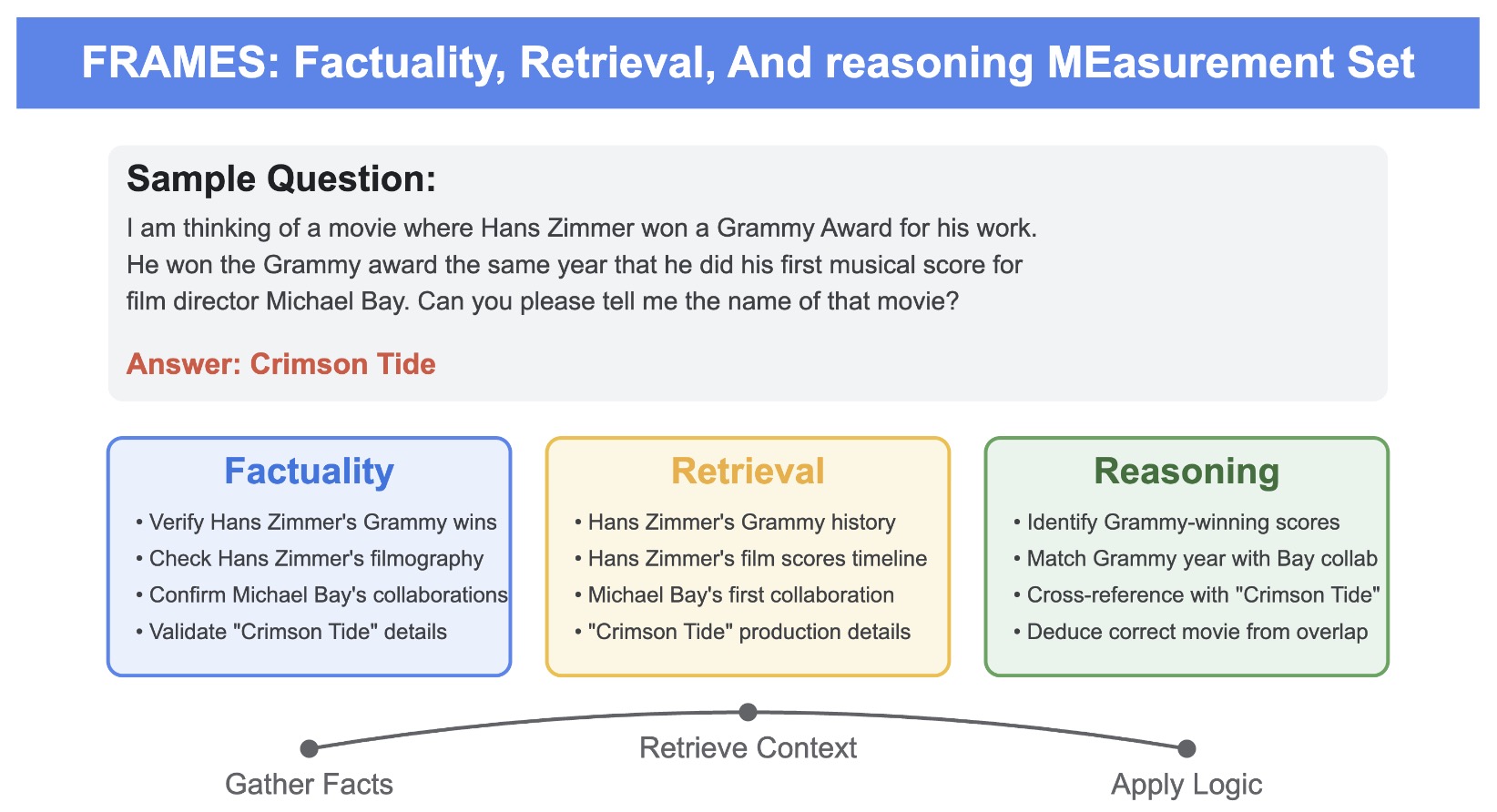

- Fact, Fetch, and Reason: A Unified Evaluation of Retrieval-Augmented Generation

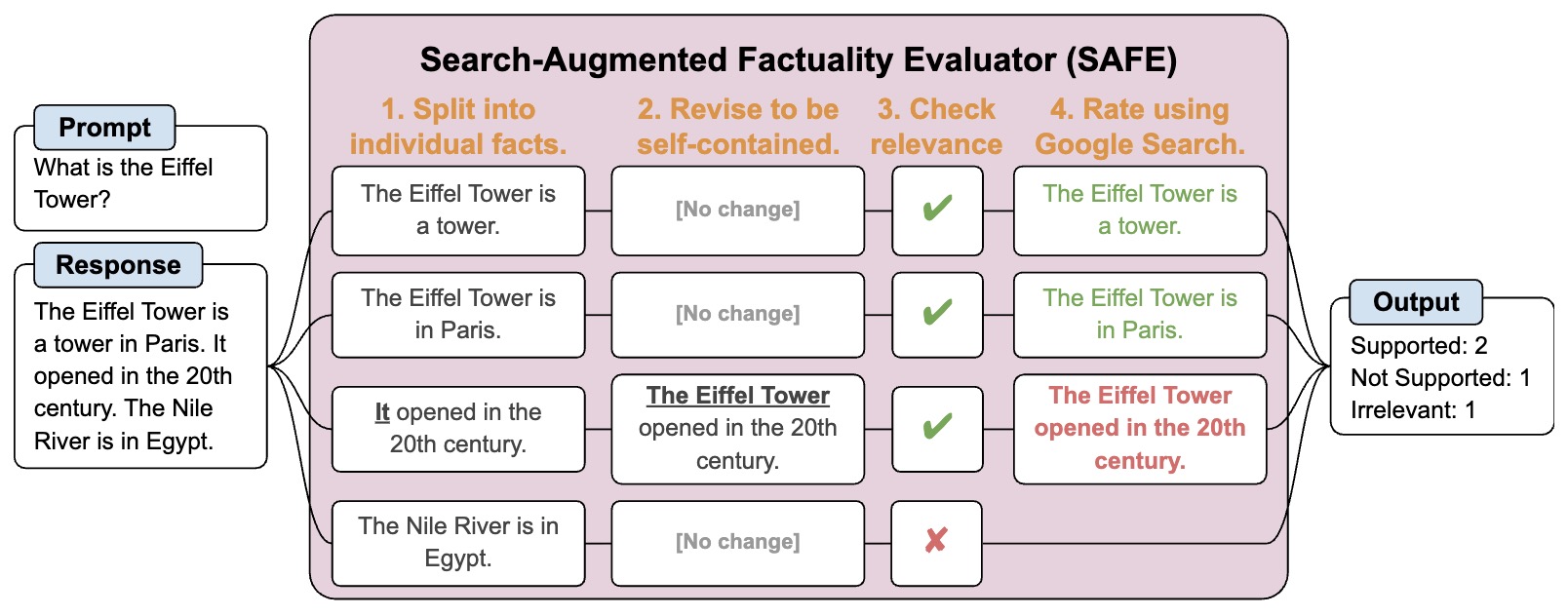

- Long-form factuality in large language models

- References

- Citation

Overview

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), as introduced in Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks by Lewis et al. (2020), is an advanced technique designed to enhance the output of Large Language Models (LLMs) by incorporating external knowledge sources.

- RAG is achieved by retrieving relevant information from a large corpus of documents and utilizing that information to guide and inform the generative process of the model. RAG improves factual grounding by conditioning LLMs on retrieved external evidence rather than relying solely on parametric memory.

- The subsequent sections provide a detailed examination of this methodology.

Motivation

- In many real-world scenarios, organizations maintain extensive collections of proprietary documents, such as technical manuals, from which precise information must be extracted. This challenge is often analogous to locating a needle in a haystack, given the sheer volume and complexity of the content.

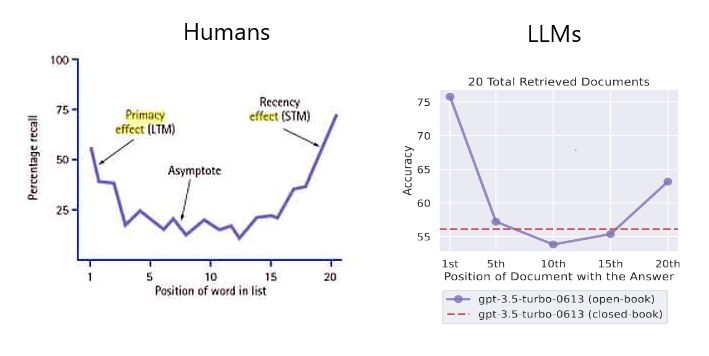

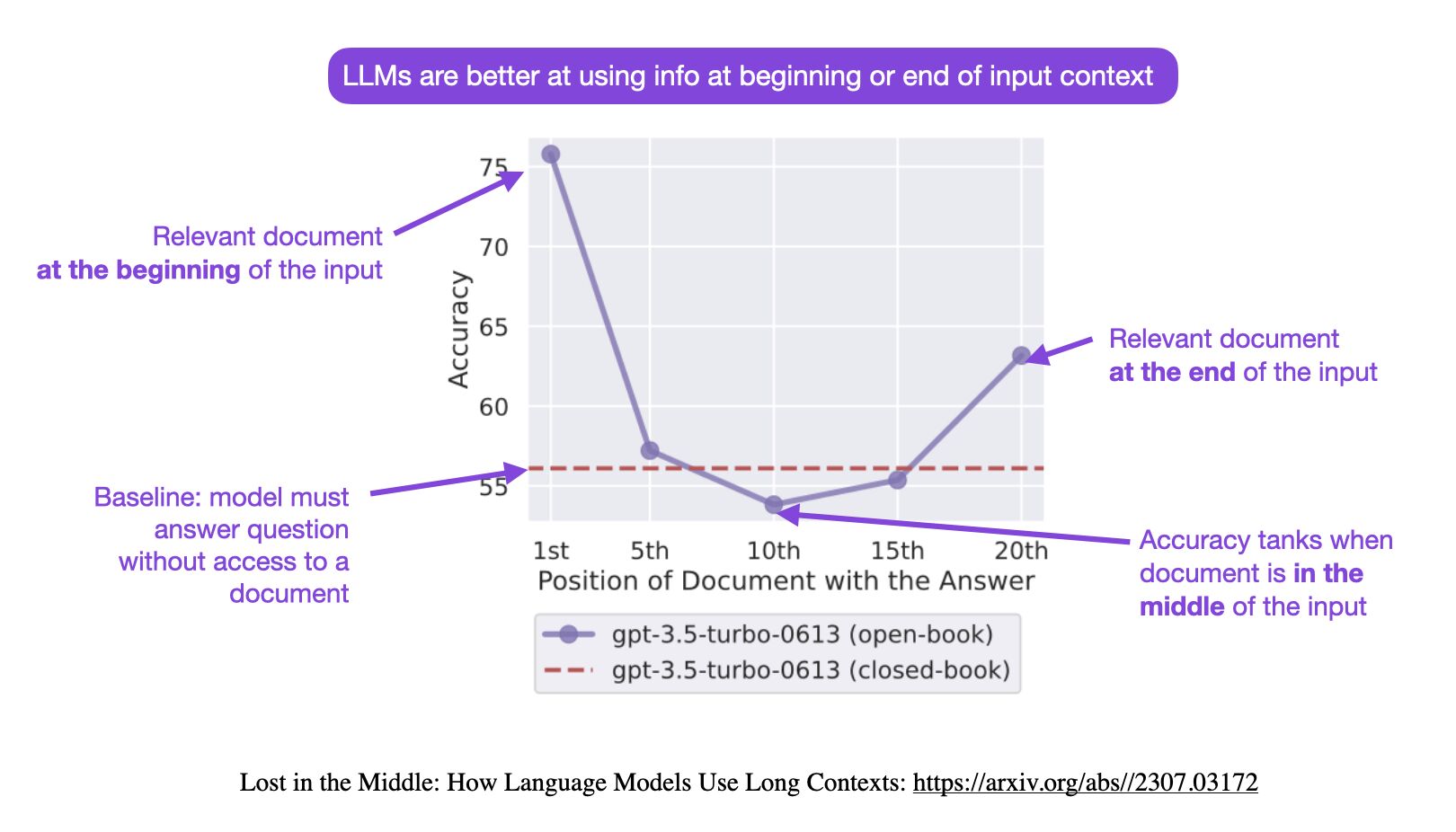

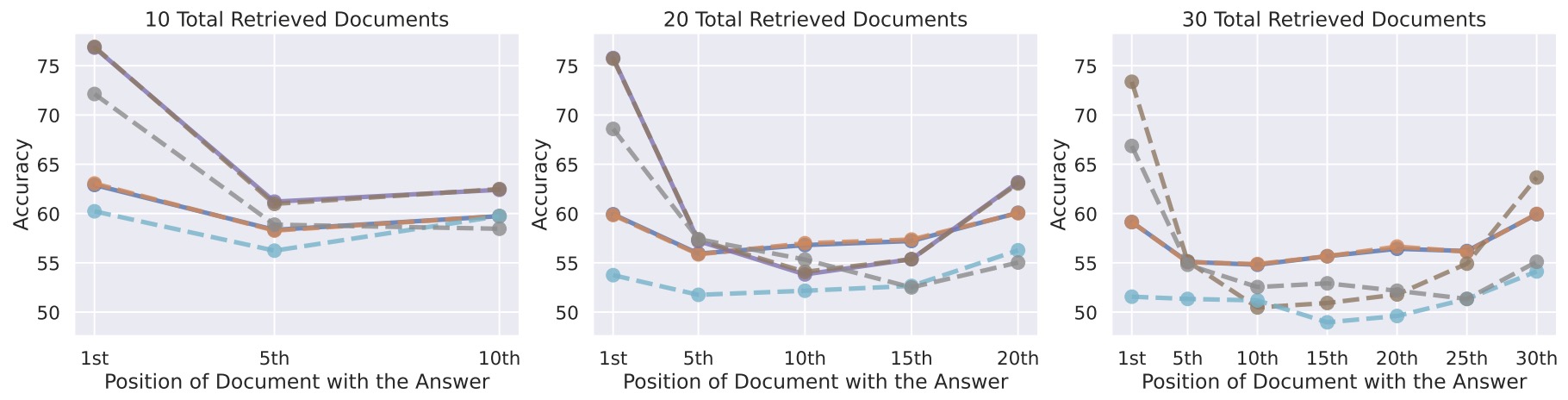

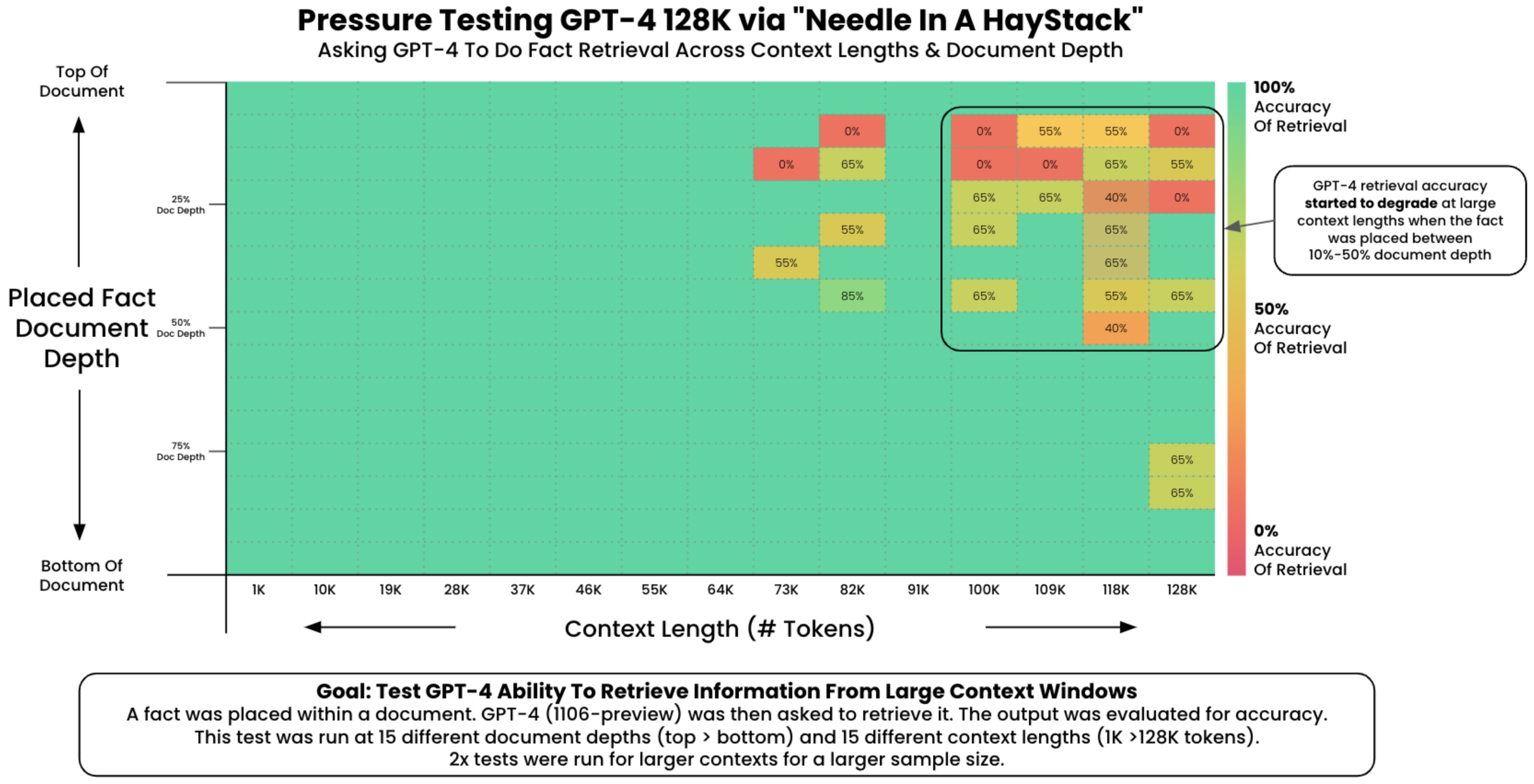

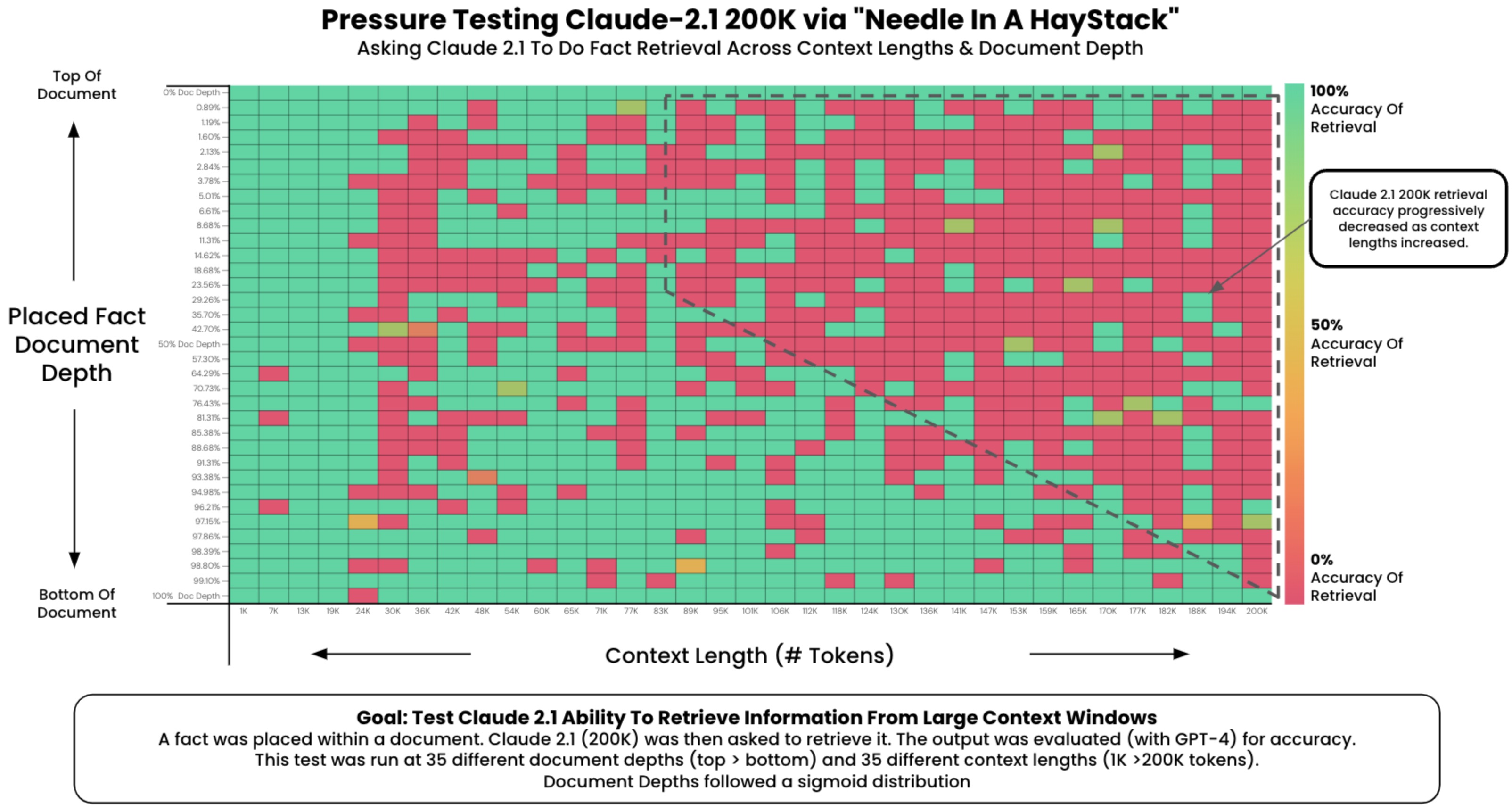

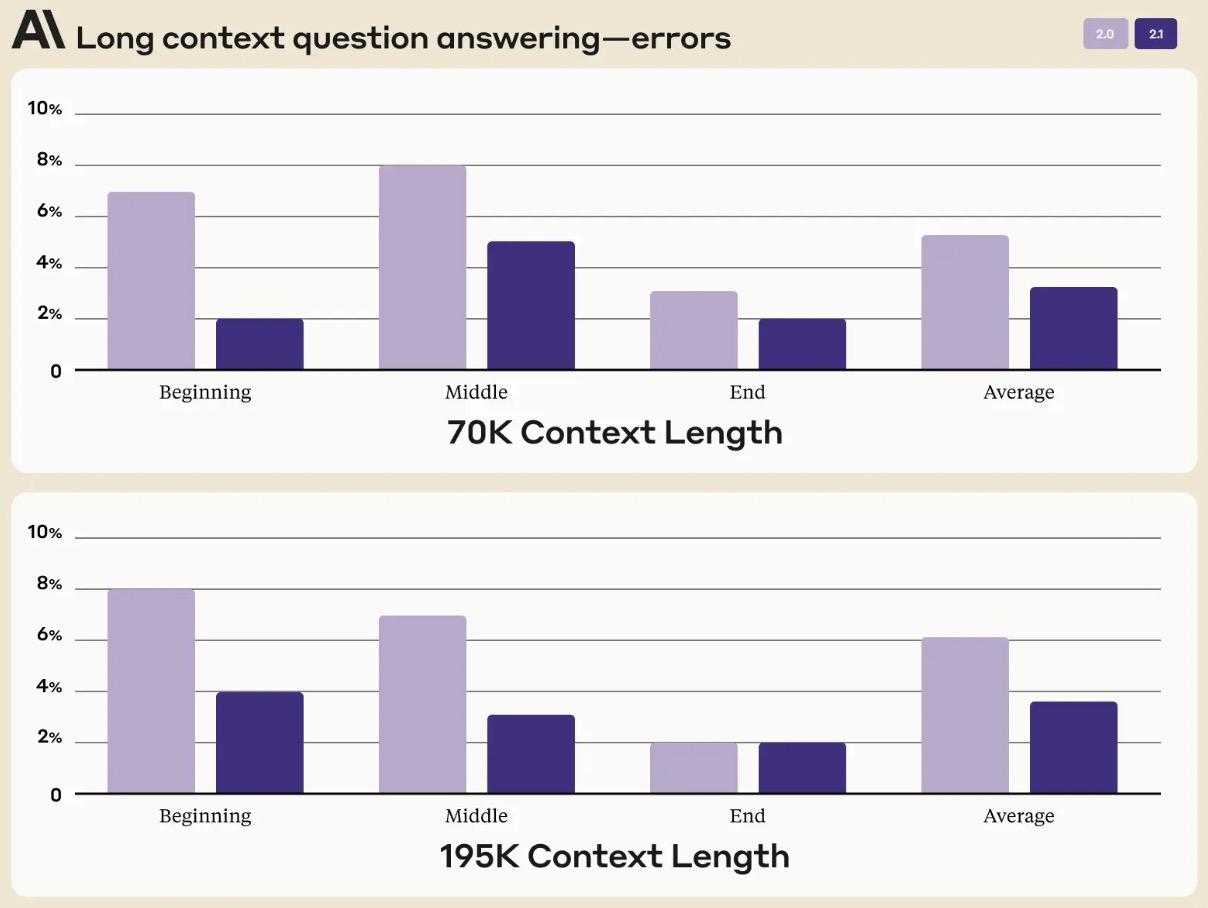

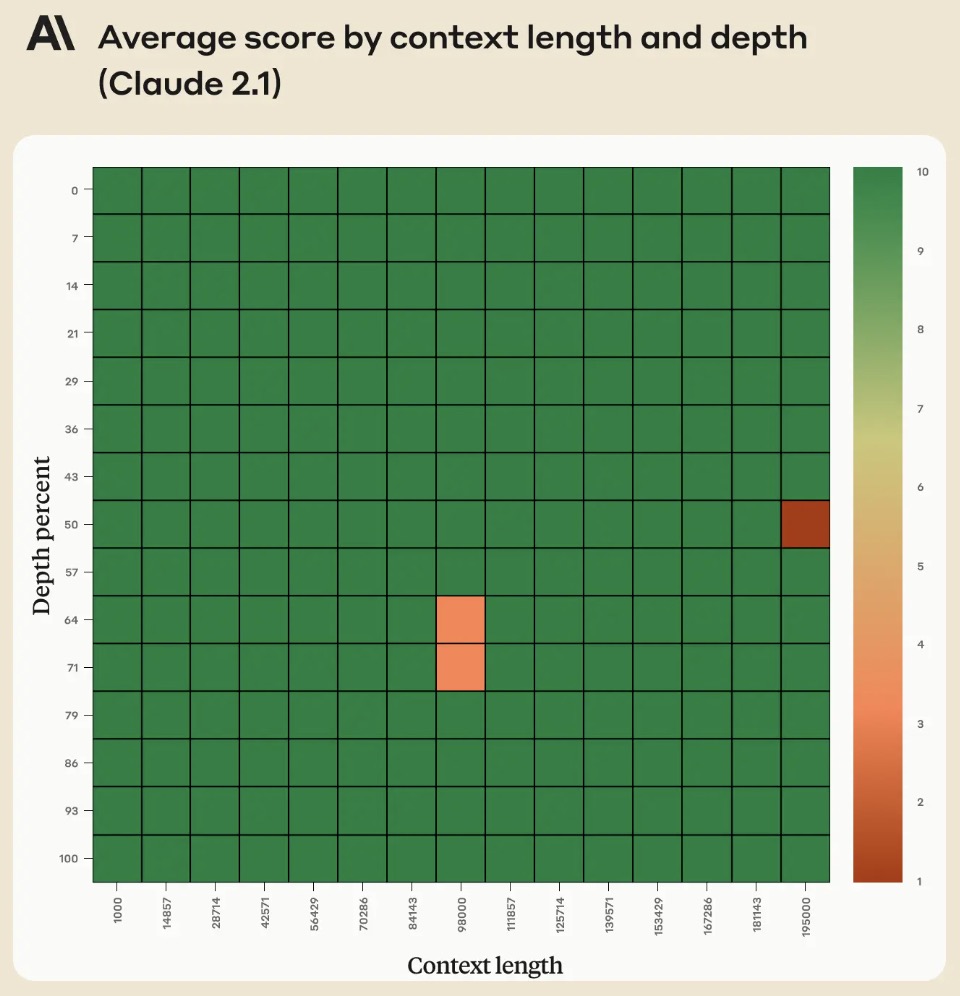

- While recent advancements, such as OpenAI’s introduction of GPT-4 Turbo, offer improved capabilities for processing lengthy documents, they are not without limitations. Notably, these models exhibit a tendency known as the “Lost in the Middle” phenomenon, wherein information positioned near the center of the context window is more likely to be overlooked or forgotten. This issue is akin to reading a comprehensive text such as the Bible, yet struggling to recall specific content from its middle chapters.

- To address this shortcoming, the RAG approach has been introduced. This method involves segmenting documents into discrete units—typically paragraphs—and creating an index for each. Upon receiving a query, the system efficiently identifies and retrieves the most relevant segments, which are then supplied to the language model. By narrowing the input to only the most pertinent information, this strategy mitigates cognitive overload within the model and substantially improves the relevance and accuracy of its responses.

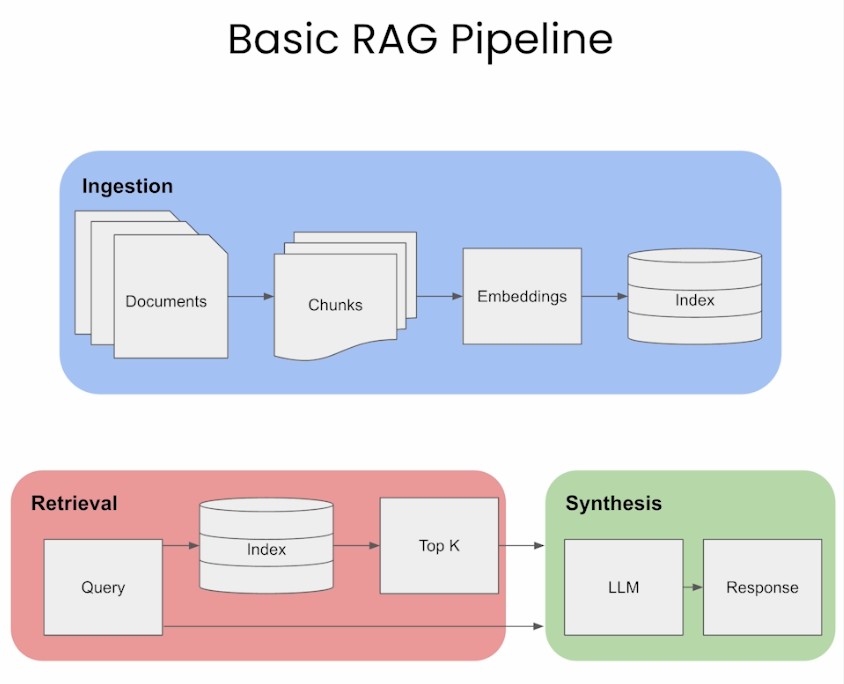

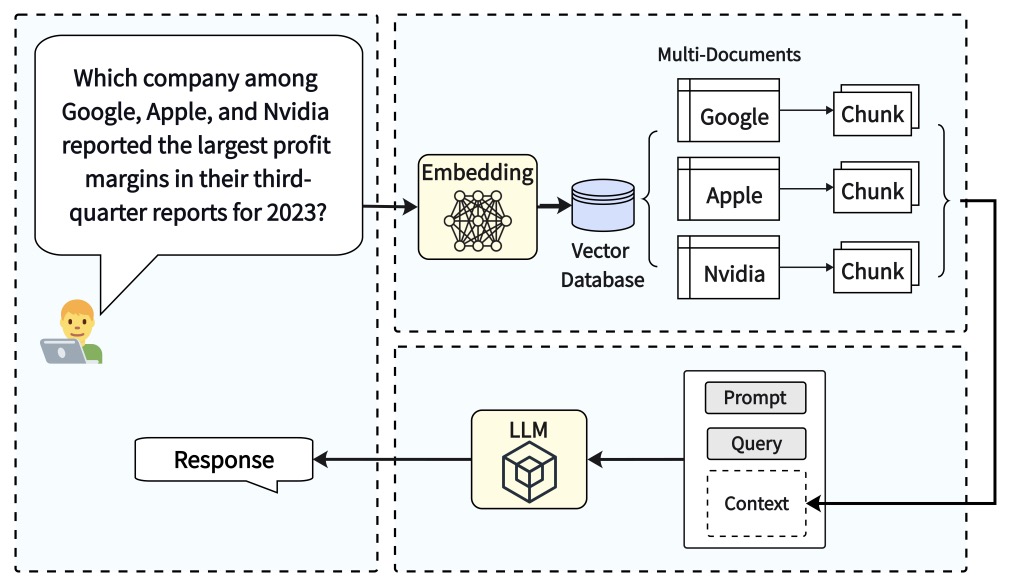

The Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) Pipeline

- With RAG, the LLM is able to leverage knowledge and information that is not necessarily in its weights by providing it access to external knowledge sources such as databases.

- It leverages a retriever to find relevant contexts to condition the LLM, in this way, RAG is able to augment the knowledge-base of an LLM with relevant documents.

- The retriever here could be any of the following depending on the need for semantic retrieval or not:

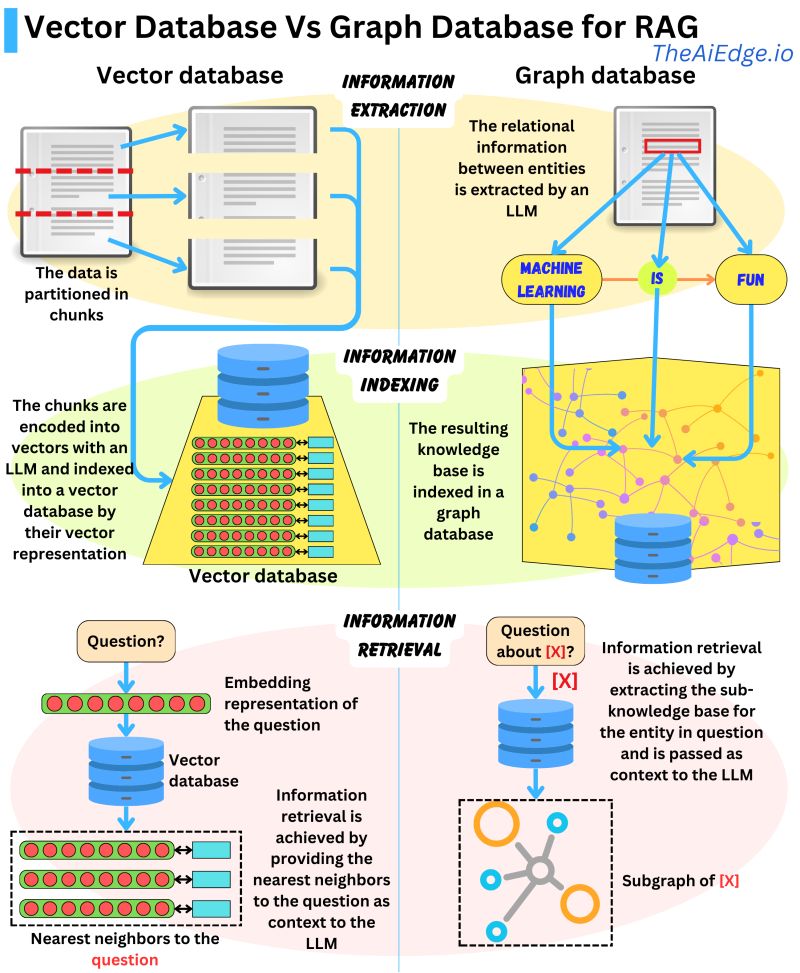

- Vector database: Typically, queries are embedded using models like BERT for generating dense vector embeddings. Alternatively, traditional methods like TF-IDF can be used for sparse embeddings. The search is then conducted based on term frequency or semantic similarity.

- Graph database: Constructs a knowledge base from extracted entity relationships within the text. This approach is precise but may require exact query matching, which could be restrictive in some applications.

- Regular SQL database: Offers structured data storage and retrieval but might lack the semantic flexibility of vector databases.

- The image below from Damien Benveniste, PhD talks a bit about the difference between using Graph vs. Vector database for RAG.

- In his post linked above, Damien states that Graph Databases are favored for Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) when compared to Vector Databases. While Vector Databases partition and index data using LLM-encoded vectors, allowing for semantically similar vector retrieval, they may fetch irrelevant data.

- Graph Databases, on the other hand, build a knowledge base from extracted entity relationships in the text, making retrievals concise. However, it requires exact query matching which can be limiting.

-

A potential solution could be to combine the strengths of both databases: indexing parsed entity relationships with vector representations in a graph database for more flexible information retrieval. It remains to be seen if such a hybrid model exists.

- After retrieving, you may want to look into filtering the candidates further by adding ranking and/or fine ranking layers that allow you to filter down candidates that do not match your business rules, are not personalized for the user, current context, or response limit.

- Let’s succinctly summarize the process of RAG and then delve into its pros and cons:

- Vector Database Creation: RAG starts by converting an internal dataset into vectors and storing them in a vector database (or a database of your choosing).

- User Input: A user provides a query in natural language, seeking an answer or completion.

- Information Retrieval: The retrieval mechanism scans the vector database to identify segments that are semantically similar to the user’s query (which is also embedded). These segments are then given to the LLM to enrich its context for generating responses.

- Combining Data: The chosen data segments from the database are combined with the user’s initial query, creating an expanded prompt.

- Generating Text: The enlarged prompt, filled with added context, is then given to the LLM, which crafts the final, context-aware response.

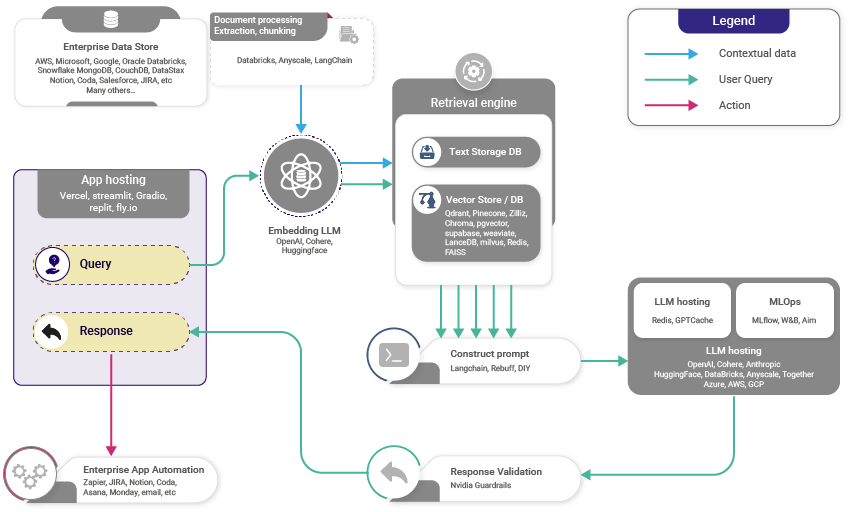

- The image below (source) displays the high-level working of RAG.

Advantages of RAG

-

RAG enhances language model outputs by grounding generation in external knowledge sources that are not contained within the model’s parameters. By retrieving relevant documents or passages at inference time, RAG enables models to produce more accurate, current, and domain-specific responses without modifying their internal weights. The following list highlights some of the distinct advantages of RAG:

-

External knowledge access: RAG allows language models to leverage information from external knowledge bases, enabling access to up-to-date, proprietary, or domain-specific data that would otherwise be unavailable or stale if stored solely in model parameters.

-

Support for dynamic and changing corpora: RAG naturally supports dynamic or frequently changing corpora, since new, updated, or removed documents can be reflected immediately through the retriever without requiring model retraining, making it well suited for evolving knowledge bases.

-

No retraining required: RAG avoids the need for expensive and time-consuming model retraining or fine-tuning, reducing computational cost and accelerating iteration while still allowing the system to incorporate new information.

-

Effective with limited labeled data: Because RAG relies on retrieval rather than supervised learning for knowledge injection, it performs well in environments where labeled training data is scarce but large volumes of unlabeled or weakly structured data are available.

-

Well-suited for real-time and knowledge-intensive applications: RAG is particularly effective for use cases such as virtual assistants, enterprise search, and question answering over technical documentation or product manuals, where accurate, real-time access to specific information is required.

-

Improved factual grounding and traceability: By explicitly retrieving and conditioning on source documents, RAG improves factual grounding and enables greater transparency and traceability in generated responses.

-

Dependence on retrieval quality: A key limitation of RAG is that its performance is bounded by the quality, coverage, and freshness of the retrieval system and underlying knowledge base; missing or incorrect retrievals can directly degrade generation quality.

-

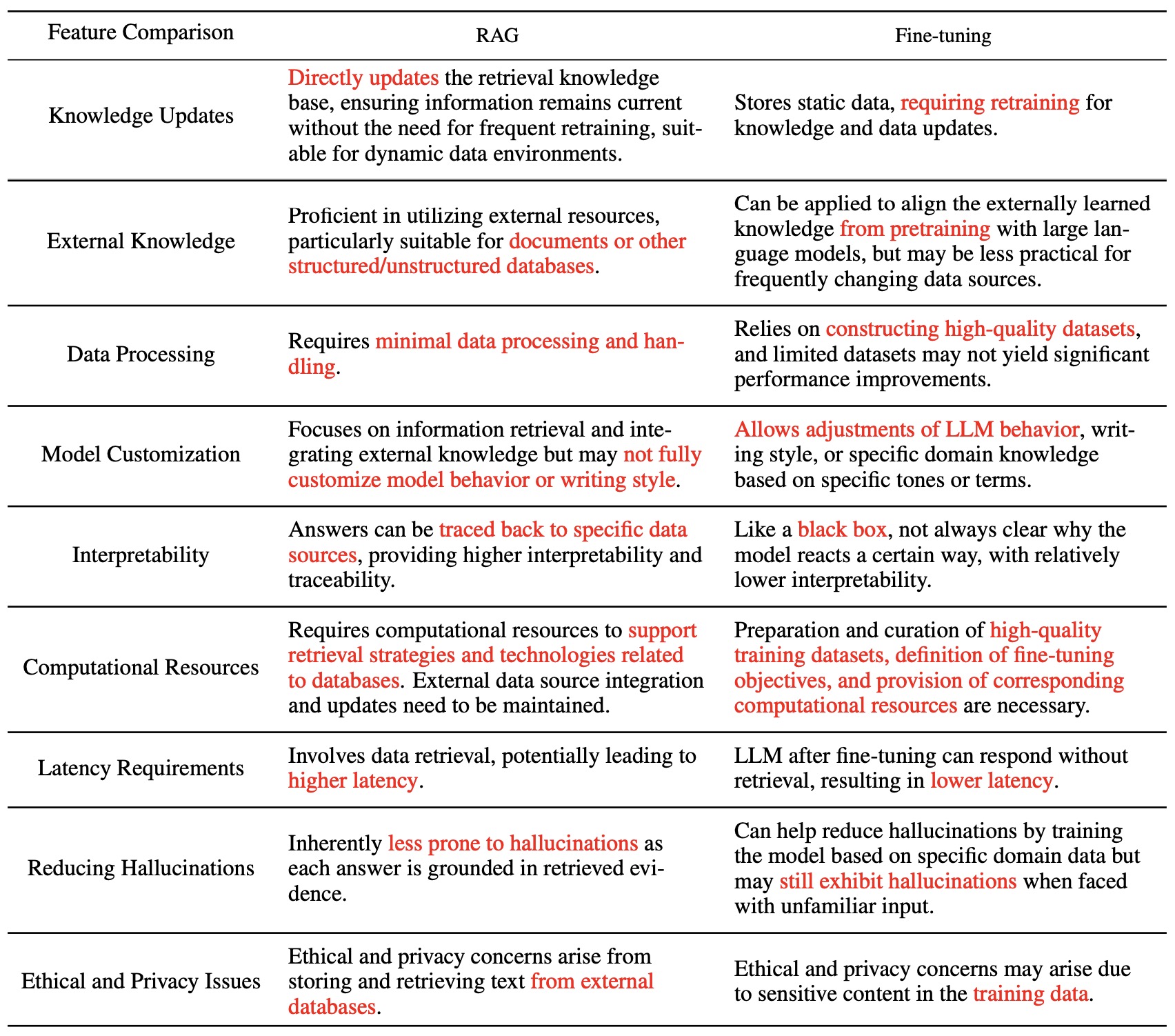

RAG vs. Fine-tuning

- The table below (source) compares RAG vs. fine-tuning.

- To summarize the above table:

- RAG offers Large Language Models (LLMs) access to factual, access-controlled, timely information. This integration enables LLMs to fetch precise and verified facts directly from relevant databases and knowledge repositories in real-time. While fine-tuning can address some of these aspects by adapting the model to specific data, RAG excels at providing up-to-date and specific information without the substantial costs associated with fine-tuning. Moreover, RAG enhances the model’s ability to remain current and relevant by dynamically accessing and retrieving the latest data, thus ensuring the responses are accurate and contextually appropriate. Additionally, RAG’s approach to leveraging external sources can be more flexible and scalable, allowing for easy updates and adjustments without the need for extensive retraining.

- Fine-tuning adapts the style, tone, and vocabulary of LLMs so that your linguistic “paint brush” matches the desired domain and style. RAG does not provide this level of customization in terms of linguistic style and vocabulary.

- Focus on RAG first. A successful LLM application typically involves connecting specialized data to the LLM workflow. Once you have a functional application, you can add fine-tuning to enhance the style and vocabulary of the system.

Ensemble of RAG

- Leveraging an ensemble of RAG systems offers a substantial upgrade to the model’s ability to produce rich and contextually accurate text. Here’s an enhanced breakdown of how this procedure could work:

- Knowledge sources: RAG models retrieve information from external knowledge stores to augment their knowledge in a particular domain. These can include passages, tables, images, etc. from domains like Wikipedia, books, news, databases.

- Combining sources: At inference time, multiple retrievers can pull relevant content from different corpora. For example, one retriever searches Wikipedia, another searches news sources. Their results are concatenated into a pooled set of candidates.

- Ranking: The model ranks the pooled candidates by their relevance to the context.

- Selection: Highly ranked candidates are selected to condition the language model for generation.

- Ensembling: Separate RAG models specialized on different corpora can be ensembled. Their outputs are merged, ranked, and voted on.

- Multiple knowledge sources can augment RAG models through pooling and ensembles. Careful ranking and selection helps integrate these diverse sources for improved generation.

- One thing to keep in mind when using multiple retrievers is to rank the different outputs from each retriever before merging them to form a response. This can be done in a variety of ways, using LTR algorithms, multi-armed bandit framework, multi-objective optimization, or according to specific business use cases.

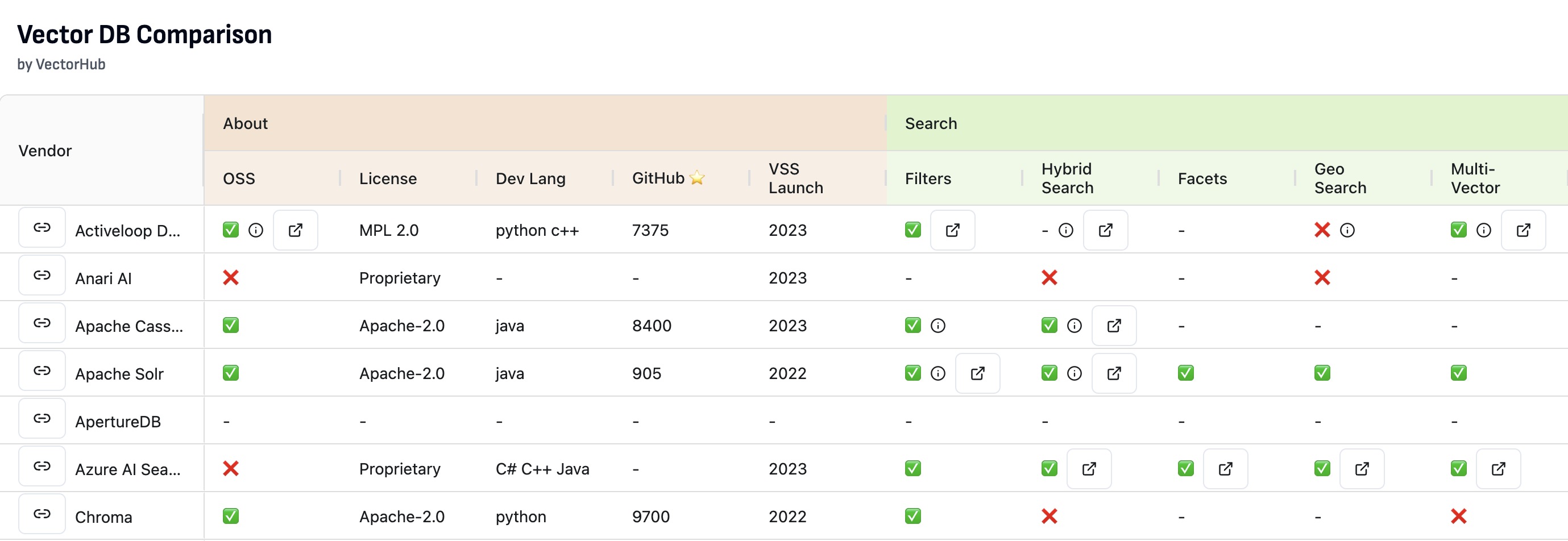

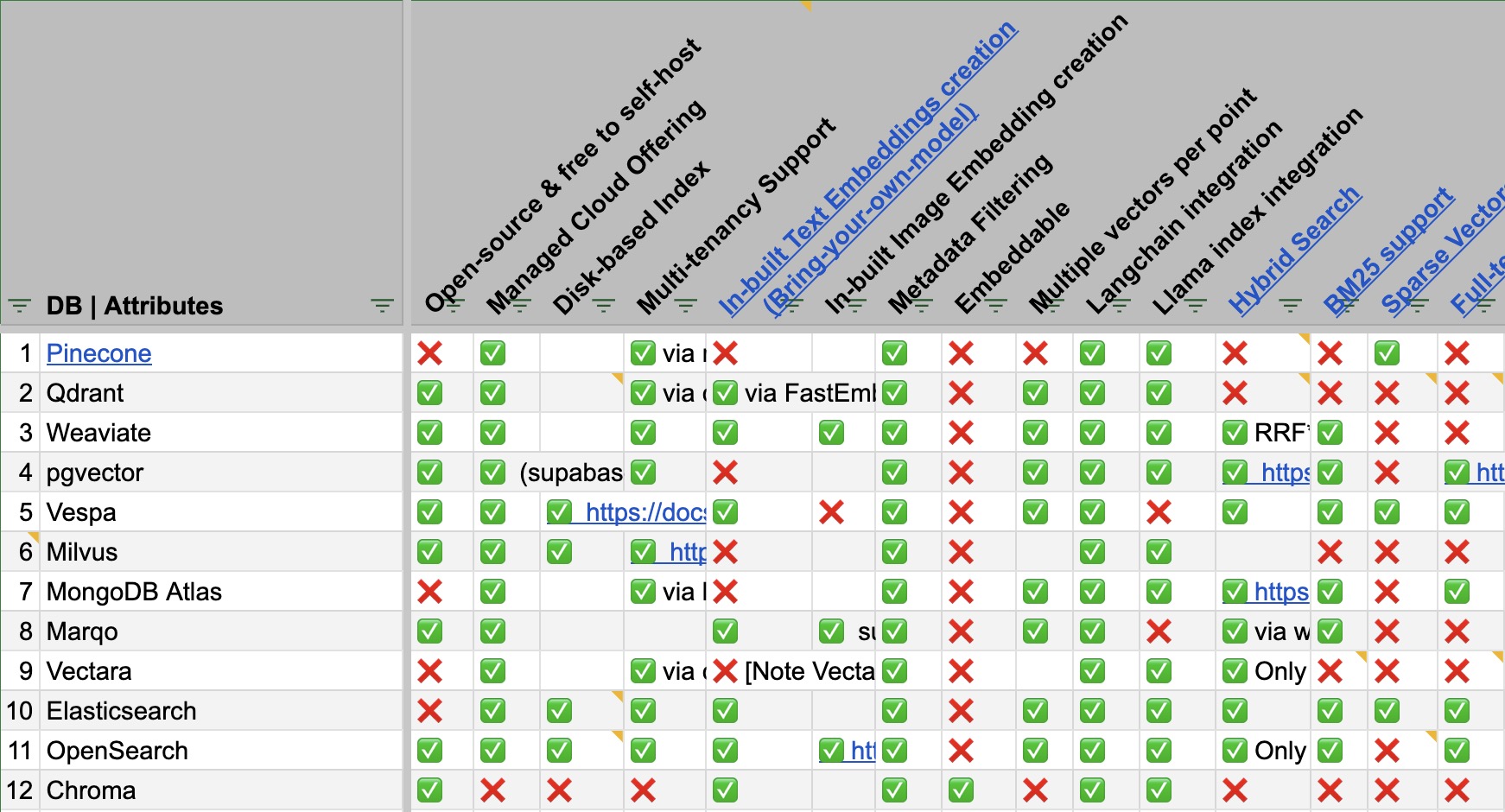

Choosing a Vector DB using a Feature Matrix

- To compare the plethora of Vector DB offerings, a feature matrix that highlights the differences between Vector DBs and which to use in which scenario is essential.

- Vector DB Comparison by VectorHub offers a great comparison spanning 37 vendors and 29 features (as of this writing).

- As a secondary resource, the following table (source) shows a comparison of some of the prevalent Vector DB offers along various feature dimensions:

- Access the full spreadsheet here.

Building a RAG pipeline

- The image below (source), gives a visual overview of the three different steps of RAG: Ingestion, Retrieval, and Synthesis/Response Generation.

- In the sections below, we will go over these key areas.

Ingestion

Chunking

- Chunking is the process of dividing the prompts and/or the documents to be retrieved, into smaller, manageable segments or chunks. These chunks can be defined either by a fixed size, such as a specific number of characters, sentences, or paragraphs. The choice of chunking strategy plays a critical role in determining both the performance and efficiency of your RAG system.

- Each chunk is encoded into an embedding vector for retrieval. Smaller, more precise chunks lead to a finer match between the user’s query and the content, enhancing the accuracy and relevance of the information retrieved.

- Larger chunks might include irrelevant information, introducing noise and potentially reducing the retrieval accuracy. By controlling the chunk size, RAG can maintain a balance between comprehensiveness and precision.

- So the next natural question that comes up is, how do you choose the right chunk size for your use case? The choice of chunk size in RAG is crucial. It needs to be small enough to ensure relevance and reduce noise but large enough to maintain the context’s integrity. Let’s look at a few methods below referred from Pinecone:

- Fixed-size Chunking: Simply decide the number of tokens in our chunk along with whether there should be overlap between them or not. Overlap between chunks guarantees there to be minimal semantic context loss between chunks. This option is computationally cheap and simple to implement.

text = "..." # your text from langchain.text_splitter import CharacterTextSplitter text_splitter = CharacterTextSplitter( separator = "\n\n", chunk_size = 256, chunk_overlap = 20 ) docs = text_splitter.create_documents([text]) - Context-aware Chunking: Content-aware chunking leverages the intrinsic structure of the text to create chunks that are more meaningful and contextually relevant. Here are several approaches to achieving this:

- Sentence Splitting: This method aligns with models optimized for embedding sentence-level content. Different tools and techniques can be used for sentence splitting:

- Naive Splitting: A basic method where sentences are split using periods and new lines. Example:

text = "..." # Your text docs = text.split(".")- This method is quick but may overlook complex sentence structures.

- NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit): A comprehensive Python library for language processing. NLTK includes a sentence tokenizer that effectively splits text into sentences. Example:

text = "..." # Your text from langchain.text_splitter import NLTKTextSplitter text_splitter = NLTKTextSplitter() docs = text_splitter.split_text(text) - spaCy: An advanced Python library for NLP tasks, spaCy offers efficient sentence segmentation. Example:

text = "..." # Your text from langchain.text_splitter import SpacyTextSplitter text_splitter = SpacyTextSplitter() docs = text_splitter.split_text(text)

- Naive Splitting: A basic method where sentences are split using periods and new lines. Example:

- Recursive Chunking: Recursive chunking is an iterative method that splits text hierarchically using various separators. It adapts to create chunks of similar size or structure by recursively applying different criteria. Example using LangChain:

text = "..." # Your text from langchain.text_splitter import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter text_splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter( chunk_size = 256, chunk_overlap = 20 ) docs = text_splitter.create_documents([text]) - Structure-based Chunking: For formatted content like Markdown, HTML, or LaTeX, specialized chunking can be applied to maintain the original structure:

- Markdown Chunking: Recognizes markdown syntax and divides content based on structure. Example:

from langchain.text_splitter import MarkdownTextSplitter markdown_text = "..." markdown_splitter = MarkdownTextSplitter(chunk_size=100, chunk_overlap=0) docs = markdown_splitter.create_documents([markdown_text]) - HTML Chunking: Leverages HTML tags (such as headings, sections, and semantic elements) to segment content while preserving document hierarchy and structural meaning.

- LaTeX Chunking: Parses LaTeX commands and environments to chunk content while preserving its logical organization.

- Markdown Chunking: Recognizes markdown syntax and divides content based on structure. Example:

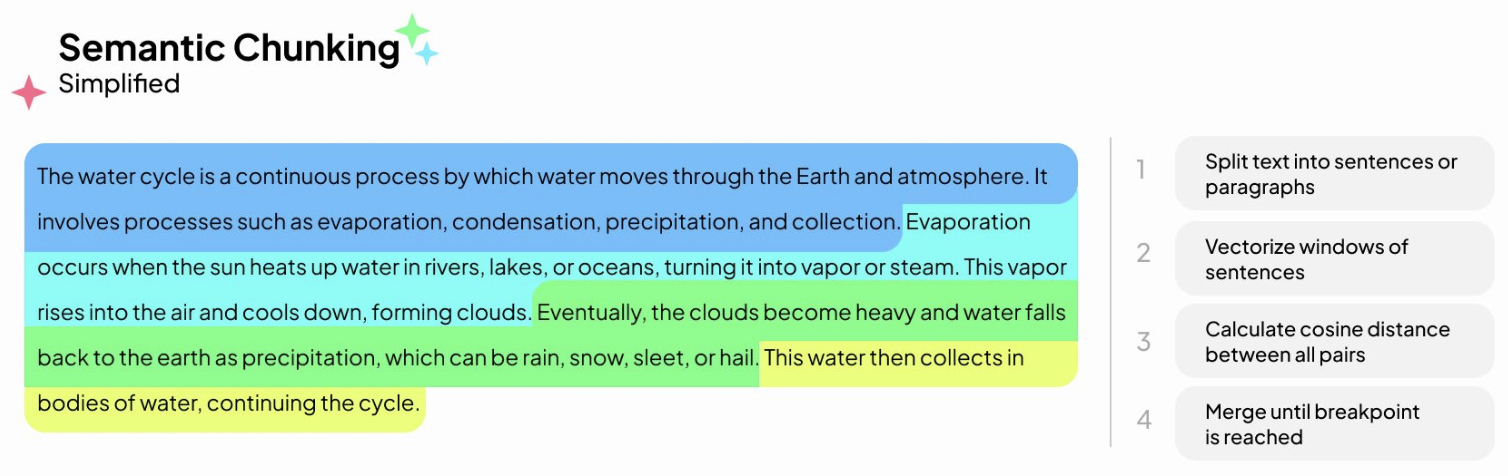

- Semantic Chunking: Segment text based on semantic similarity. This means that sentences with the strongest semantic connections are grouped together, while sentences that move to another topic or theme are separated into distinct chunks. For an implementation of semantic chunking, please refer to this notebook.

- Semantic chunking can be summarized in four steps:

- Split the text into sentences, paragraphs, or other rule-based units.

- Vectorize a window of sentences or other units.

- Calculate the cosine distance between the embedded windows.

- Merge sentences or units until the cosine similarity value reaches a specific threshold.

- The following figure (source) visually summarizes the overall process:

- Semantic chunking can be summarized in four steps:

- Sentence Splitting: This method aligns with models optimized for embedding sentence-level content. Different tools and techniques can be used for sentence splitting:

- Fixed-size Chunking: Simply decide the number of tokens in our chunk along with whether there should be overlap between them or not. Overlap between chunks guarantees there to be minimal semantic context loss between chunks. This option is computationally cheap and simple to implement.

- As a rule of thumb, if the chunk of text makes sense without the surrounding context to a human, it will make sense to the language model as well. Therefore, finding the optimal chunk size for the documents in the corpus is crucial to ensuring that the search results are accurate and relevant.

Figuring out the ideal chunk size

- Choosing the right chunk size is foundational to building an effective RAG system. It directly influences retrieval quality, model efficiency, and how well the system captures relevant context for downstream tasks. Poor chunking can lead to fragmented information or excessive context loss, undermining overall performance.

-

Building a RAG system involves determining the ideal chunk sizes for the documents that the retriever component will process. The ideal chunk size depends on several factors:

-

Data Characteristics: The nature of your data is crucial. For text documents, consider the average length of paragraphs or sections. If the documents are well-structured with distinct sections, these natural divisions might serve as a good basis for chunking.

-

Retriever Constraints: The retriever model you choose (like BM25, TF-IDF, or a neural retriever like DPR) might have limitations on the input length. It’s essential to ensure that the chunks are compatible with these constraints.

-

Memory and Computational Resources: Larger chunk sizes can lead to higher memory usage and computational overhead. Balance the chunk size with the available resources to ensure efficient processing.

-

Task Requirements: The nature of the task (e.g., question answering, document summarization) can influence the ideal chunk size. For detailed tasks, smaller chunks might be more effective to capture specific details, while broader tasks might benefit from larger chunks to capture more context.

-

Experimentation: Often, the best way to determine the ideal chunk size is through empirical testing. Run experiments with different chunk sizes and evaluate the performance on a validation set to find the optimal balance between granularity and context.

-

Overlap Consideration: Sometimes, it’s beneficial to have overlap between chunks to ensure that no important information is missed at the boundaries. Decide on an appropriate overlap size based on the task and data characteristics.

-

- To summarize, determining the ideal chunk size for a RAG system is a balancing act that involves considering the characteristics of your data, the limitations of your retriever model, the resources at your disposal, the specific requirements of your task, and empirical experimentation. It’s a process that may require iteration and fine-tuning to achieve the best results.

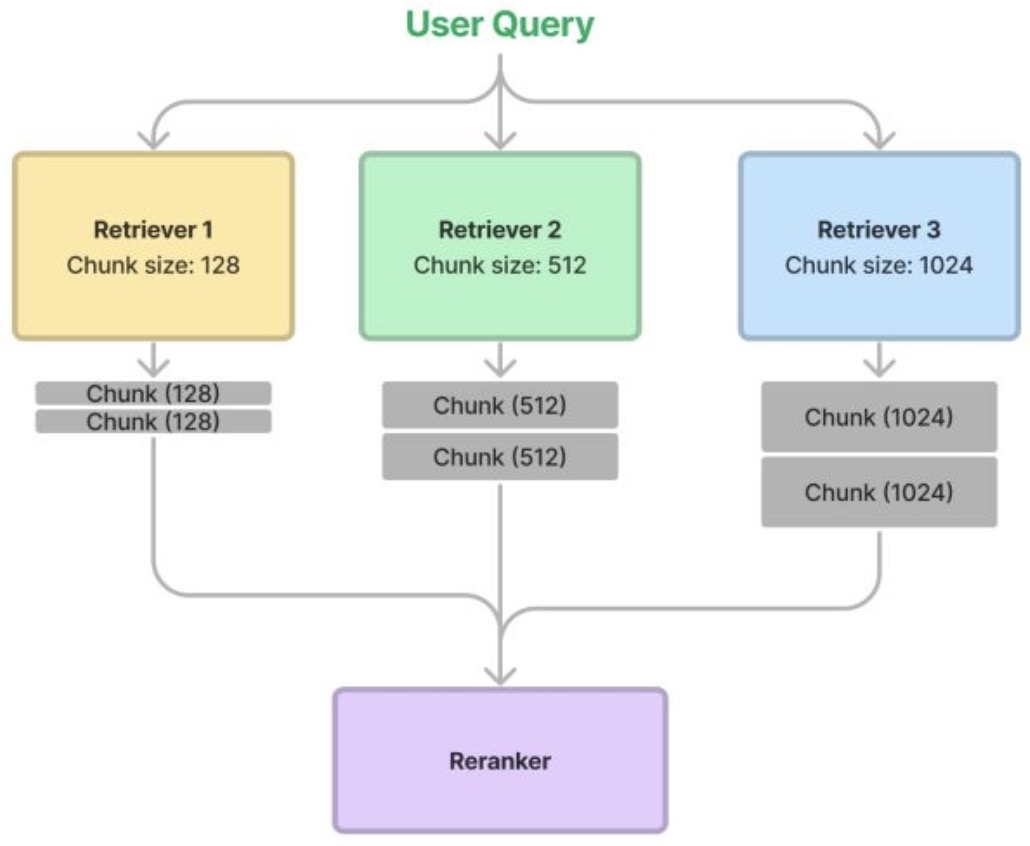

Retriever Ensembling and Re-ranking

- In some scenarios, it may be beneficial to simultaneously utilize multiple chunk sizes and apply a re-ranking mechanism to refine the retrieved results. A detailed discourse on re-ranking is available in the Re-ranking section.

- This approach serves two primary purposes:

- It potentially improves the quality of retrieved content—albeit at increased computational cost—by aggregating outputs from multiple chunking strategies, provided the re-ranker performs with a reasonable degree of accuracy.

- It enables systematic comparison of different retrieval methods relative to the re-ranker’s effectiveness.

-

The methodology proceeds as follows:

- Segment the same source document using various chunk sizes, for example: 128, 256, 512, and 1024 tokens.

- During the retrieval phase, extract relevant segments from each retrieval method, thereby forming an ensemble of retrievers.

- Apply a re-ranking model to prioritize and filter the aggregated results.

- The following diagram (source) illustrates the process.

- According to evaluation data provided by LlamaIndex, the ensemble retrieval strategy leads to a modest improvement in faithfulness metrics, suggesting slightly enhanced relevance of retrieved content. However, pairwise comparisons show equal preference between the ensembled and baseline approaches, thereby leaving the superiority of ensembling open to debate.

- It is important to note that this ensembling methodology is not limited to variations in chunk size. It can also be extended to other dimensions of a RAG pipeline, including vector-based, keyword-based, and hybrid search strategies.

Embeddings

- Once you have your prompt chunked appropriately, the next step is to embed it. Embedding prompts and documents in RAG involves transforming both the user’s query (prompt) and the documents in the knowledge base into a format that can be effectively compared for relevance. This process is critical for RAG’s ability to retrieve the most relevant information from its knowledge base in response to a user query. Here’s how it typically works:

- One option to help pick which embedding model would be best suited for your task is to look at HuggingFace’s Massive Text Embedding Benchmark (MTEB) leaderboard. There is a question of whether a dense or sparse embedding can be used so let’s look into benefits of each below:

- Sparse embedding: Sparse embeddings such as TF-IDF are great for lexical matching the prompt with the documents. Best for applications where keyword relevance is crucial. It’s computationally less intensive but may not capture the deeper semantic meanings in the text.

- Semantic embedding: Semantic embeddings, such as BERT or SentenceBERT lend themselves naturally to the RAG use-case.

- BERT: Suitable for capturing contextual nuances in both the documents and queries. Requires more computational resources compared to sparse embeddings but offers more semantically rich embeddings.

- SentenceBERT: Ideal for scenarios where the context and meaning at the sentence level are important. It strikes a balance between the deep contextual understanding of BERT and the need for concise, meaningful sentence representations. This is usually the preferred route for RAG.

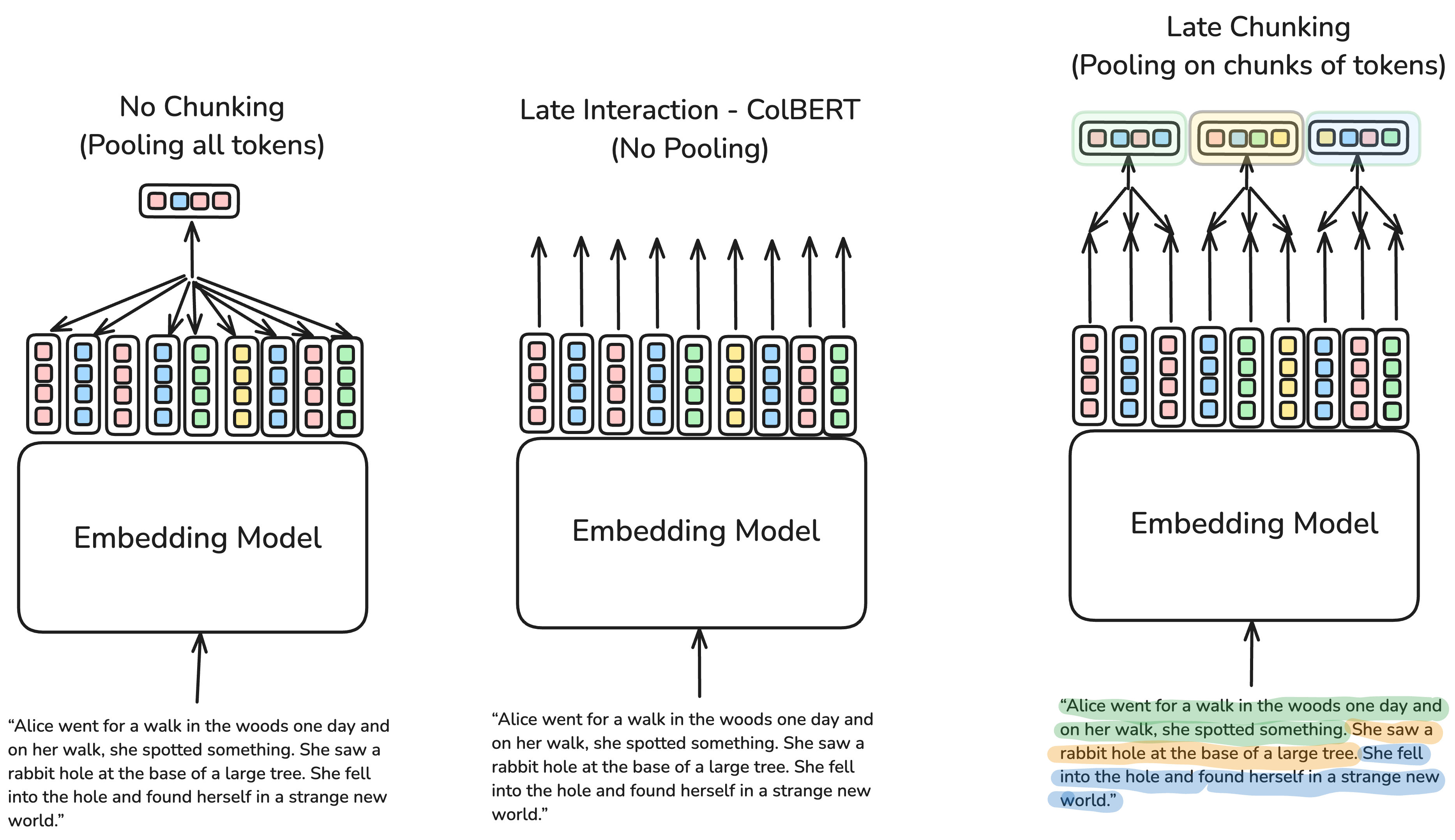

Naive Chunking vs. Late Chunking vs. Late Interaction (ColBERT and ColPali)

-

The choice between naive chunking, late chunking, and late interaction (ColBERT and ColPali) depends on the specific requirements of the retrieval task:

- Naive Chunking is suitable for scenarios with strict resource constraints but where retrieval precision is less critical.

- Late Chunking, introduced by JinaAI, offers an attractive middle ground, maintaining context and providing improved retrieval accuracy without incurring significant additional costs. Put simply, late chunking balances the trade-offs between cost and precision, making it an excellent option for building scalable and effective RAG systems, particularly in long-context retrieval scenarios.

- Late Interaction (ColBERT and ColPali) is best suited for applications where retrieval precision is paramount and resource costs are less of a concern.

-

Let’s explore the differences between three primary strategies: Naive Chunking, Late Chunking, and Late Interaction (ColBERT and ColPali), focusing on their methodologies, advantages, and trade-offs.

Overview

- Long-context retrieval presents a challenge when balancing precision, context retention, and cost efficiency. Solutions range from simple and low-cost, like Naive Chunking, to more sophisticated and resource-intensive approaches, such as Late Interaction (ColBERT and ColPali). Late Chunking, a novel approach by JinaAI, offers a middle ground, preserving context with efficiency comparable to Naive Chunking.

Naive/Vanilla Chunking

What is Naive/Vanilla Chunking?

- As discussed in the Chunking section, naive/vanilla chunking divides a document into fixed-size chunks based on metrics like sentence boundaries or token count (e.g., 512 tokens per chunk).

- Each chunk is independently embedded into a vector without considering the context of neighboring chunks.

Example

-

Consider the following paragraph: Alice went for a walk in the woods one day and on her walk, she spotted something. She saw a rabbit hole at the base of a large tree. She fell into the hole and found herself in a strange new world.

-

If chunked by sentences:

- Chunk 1: “Alice went for a walk in the woods one day and on her walk, she spotted something.”

- Chunk 2: “She saw a rabbit hole at the base of a large tree.”

- Chunk 3: “She fell into the hole and found herself in a strange new world.”

Advantages and Limitations

- Advantages:

- Efficient in terms of storage and computation.

- Simple to implement and integrate with most retrieval pipelines.

- Limitations:

- Context Loss: Each chunk is processed independently, leading to a loss of contextual relationships. For example, the connection between “she” and “Alice” would be lost, reducing retrieval accuracy for context-heavy queries like “Where did Alice fall?”.

- Fragmented Meaning: Splitting paragraphs or semantically related sections can dilute the meaning of each chunk, reducing retrieval precision.

Late Chunking

What is Late Chunking?

- Late Chunking flips the order of vectorizing (i.e., embedding generation) and chunking compared to naive/vanilla chunking. In other words, it delays the chunking process until after the entire document has been embedded into token-level representations. This allows chunks to retain context from the full document, leading to richer, more contextually aware embeddings.

How Late Chunking Works

- Embedding First: The entire document is embedded into token-level representations using a long context model.

- Chunking After: After embedding, the token-level representations are pooled into chunks based on a predefined chunking strategy (e.g., 512-token chunks).

- Context Retention: Each chunk retains contextual information from the full document, allowing for improved retrieval precision without increasing storage costs.

Example

- Using the same paragraph:

- The entire paragraph is first embedded as a whole, preserving the relationships between all sentences.

- The document is then split into chunks after embedding, ensuring that chunks like “She fell into the hole…” are contextually aware of the mention of “Alice” from earlier sentences.

Advantages and Trade-offs

- Advantages:

- Context Preservation: Late chunking ensures that the relationship between tokens across different chunks is maintained.

- Efficiency: Late chunking requires the same amount of storage as naive chunking while significantly improving retrieval accuracy.

- Trade-offs:

- Requires Long Context Models: To embed the entire document at once, a model with long-context capabilities (e.g., supporting up to 8192 tokens) is necessary.

- Slightly Higher Compute Costs: Late chunking introduces an extra pooling step after embedding, although it’s more efficient than late interaction approaches like ColBERT.

Late Interaction

What is Late Interaction?

- Late Interaction refers to a retrieval approach where token embeddings for both the document and the query are computed separately and compared at the token level, without any pooling operation. The key advantage is fine-grained, token-level matching, which improves retrieval accuracy.

ColBERT: Late Interaction in Practice

- ColBERT (Contextualized Late Interaction over BERT) by Khattab et al. (2020) uses late interaction to compare individual token embeddings from the query and document using a MaxSim operator. This allows for granular, token-to-token comparisons, which results in highly precise matches but at a significantly higher storage cost.

MaxSim: A Key Component of ColBERT

- MaxSim (Maximum Similarity) is a core component of the ColBERT retrieval framework. It refers to a specific way of calculating the similarity between token embeddings of a query and document during retrieval.

- Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of how MaxSim works:

- Token-level Embedding Comparisons:

- When a query is processed, it is tokenized and each token is embedded separately (e.g., “apple” and “sweet”).

- The document is already indexed at the token level, meaning that each token in the document also has its own embedding.

- Similarity Computation:

- At query time, the system compares each query token embedding to every token embedding in the document. The similarity between two token embeddings is often measured using a dot product or cosine similarity.

- For example, given a query token

"apple"and a document containing tokens like"apple","banana", and"fruit", the system computes the similarity of"apple"to each of these tokens.

- Selecting Maximum Similarity (MaxSim):

- The system selects the highest similarity score between the query token and the document tokens. This is known as the MaxSim operation.

- In the above example, the system compares the similarity of

"apple"(query token) with all document tokens and selects the highest similarity score, say between"apple"and the corresponding token"apple"in the document.

- MaxSim Aggregation:

The MaxSim scores for each token in the query are aggregated (i.e., summed up) to calculate a final relevance score for the document with respect to the query.

- This approach allows for token-level precision, capturing subtle nuances in the document-query matching that would be lost with traditional pooling methods.

- Token-level Embedding Comparisons:

Example

-

Consider the query

"sweet apple"and two documents:- Document 1: “The apple is sweet and crisp.”

- Document 2: “The banana is ripe and yellow.”

-

Each query token,

"sweet"and"apple", is compared with every token in both documents:- For Document 1,

"sweet"has a high similarity with"sweet"in the document, and"apple"has a high similarity with"apple". - For Document 2,

"sweet"does not have a strong match with any token, and"apple"does not appear.

- For Document 1,

-

Using MaxSim, Document 1 would have a higher relevance score for the query than Document 2 because the most similar tokens in Document 1 (i.e.,

"sweet"and"apple") align more closely with the query tokens.

Advantages and Trade-offs

- Advantages:

- High Precision: ColBERT’s token-level comparisons, facilitated by MaxSim, lead to highly accurate retrieval, particularly for specific or complex queries.

- Flexible Query Matching: By calculating similarity at the token level, ColBERT can capture fine-grained relationships that simpler models might overlook.

- Trade-offs:

- Storage Intensive: Storing all token embeddings for each document can be extremely costly. For example, storing token embeddings for a corpus of 100,000 documents could require upwards of 2.46 TB.

- Computational Complexity: While precise, MaxSim increases computational demands at query time, as each token in the query must be compared to all tokens in the document.

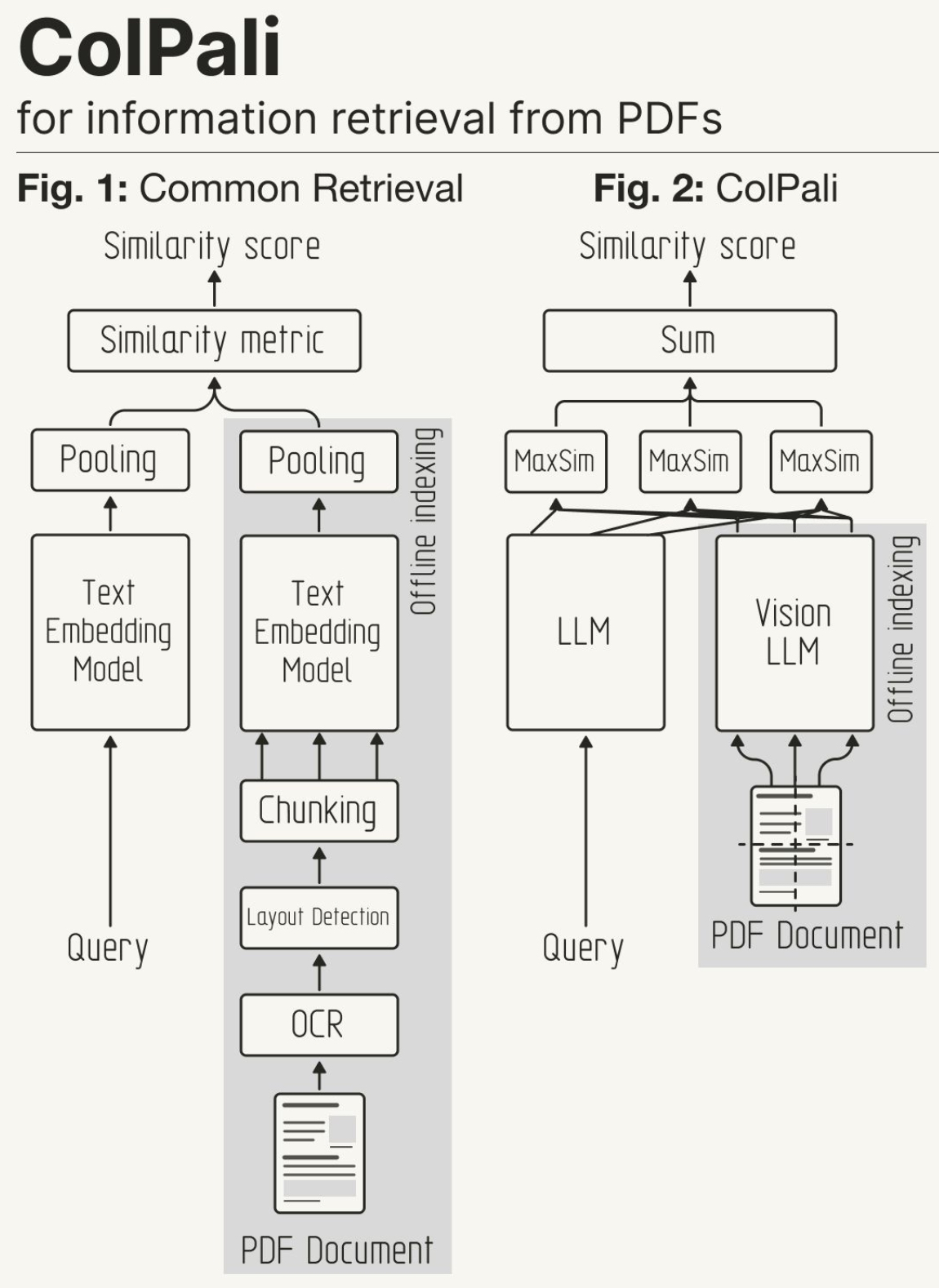

ColPali: Expanding to Multimodal Late-Interaction Retrieval

- ColPali by Faysse et al. (2024) integrates the late interaction mechanism from ColBERT with a Vision Language Model (VLM) called PaliGemma to handle multimodal documents, such as PDFs with text, images, and tables. Instead of relying on OCR and layout parsing, ColPali uses screenshots of PDF pages to directly embed both visual and textual content. This enables powerful multimodal retrieval in complex documents.

Example

- Consider a complex PDF with both text and images. ColPali treats each page as an image and embeds it using a VLM. When a user queries the system, the query is matched with embedded screenshots via late interaction, improving the ability to retrieve relevant pages based on both visual and textual content.

Comparative Analysis

| Metric | Naive Chunking | Late Chunking | Late Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Storage Requirements | Minimal storage, ~4.9 GB for 100,000 documents | Same as naive chunking, ~4.9 GB for 100,000 documents | Extremely high storage, ~2.46 TB for 100,000 documents |

| Retrieval Precision | Lower precision due to context fragmentation | Improved precision by retaining context across chunks | Highest precision with token-level matching |

| Complexity and Cost | Simple implementation, minimal resources | Moderately more complex, efficient in compute and storage | Highly complex, resource-intensive in both storage and computation |

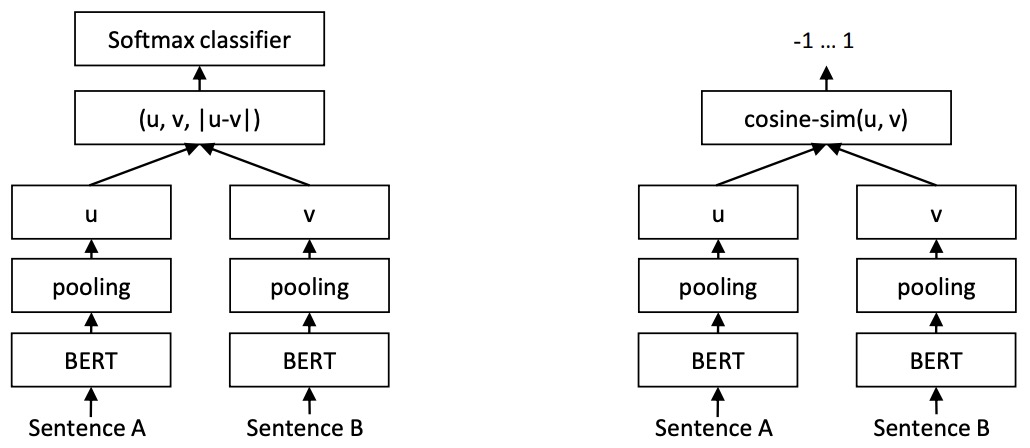

Sentence Embeddings: The What and Why

- Motivation:

- Before the introduction of Sentence-BERT (SBERT), applying BERT to semantic similarity or retrieval tasks was computationally infeasible at scale. BERT operated as a cross-encoder, where each sentence pair required a joint forward pass with full cross-attention, resulting in \(O(n^2)\) complexity. Using raw BERT embeddings—such as averaging token vectors or taking the

[CLS]output—performed worse than earlier static embedding models like GloVe, meaning embeddings couldn’t be precomputed or efficiently compared. Consequently, BERT was limited to re-ranking a small number of candidate sentences rather than performing large-scale semantic retrieval. - SBERT addressed this limitation by fine-tuning BERT in a Siamese or triplet configuration, enabling independent computation of sentence embeddings. This allowed \(O(n)\) embedding computations followed by lightweight cosine similarity comparisons, reducing semantic search computation from roughly 65 hours to 5 seconds while preserving accuracy. This breakthrough laid the foundation for modern dense retrieval, dual-encoder architectures, and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) systems, all of which depend on scalable, precomputable embeddings.

- Before the introduction of Sentence-BERT (SBERT), applying BERT to semantic similarity or retrieval tasks was computationally infeasible at scale. BERT operated as a cross-encoder, where each sentence pair required a joint forward pass with full cross-attention, resulting in \(O(n^2)\) complexity. Using raw BERT embeddings—such as averaging token vectors or taking the

Background: Differences compared to Token-Level Models like BERT

-

As an overview, let’s look into how sentence transformers differ compared to token-level embedding models such as BERT.

-

Sentence Transformers are a modification of the traditional BERT model, tailored specifically for generating embeddings of entire sentences (i.e., sentence embeddings). The key differences in their training approaches are:

- Objective: BERT is trained to predict masked words and next sentence prediction. Sentence Transformers, as introduced in Sentence-BERT by Reimers and Gurevych (2019), are fine-tuned specifically to understand relationships between sentences. They produce embeddings where semantically similar sentences are close in vector space, typically using cosine similarity as the comparison metric.

- Level of Embedding: BERT provides contextualized token embeddings, while Sentence Transformers produce a single, semantically meaningful embedding for the entire sentence by applying a pooling operation to the transformer’s output.

- Training Data and Tasks: SBERT is fine-tuned using datasets like SNLI and MultiNLI, which contain labeled sentence pairs (entailment, contradiction, neutral). This contrastive supervision enables it to learn sentence-level semantics that generalize well to similarity tasks.

- Siamese and Triplet Network Structures: SBERT introduces a siamese or triplet architecture where two or three BERT models (sharing weights) encode input sentences into embeddings. During training, these embeddings are optimized so that semantically close sentences have higher cosine similarity and dissimilar ones have lower similarity.

- Pooling Strategies: To obtain a fixed-size vector, SBERT applies pooling over the last hidden layer of BERT. The paper experiments with three strategies—mean pooling, max pooling, and using the

[CLS]token output—with mean pooling performing best. - Fine-Tuning Objectives: Depending on available supervision, SBERT can use classification (softmax over concatenated embeddings and element-wise differences), regression (cosine similarity with mean-squared error), or triplet loss objectives to align embeddings of related sentences.

- For the classification objective, the embeddings \(u\) and \(v\) are concatenated with their element-wise absolute difference \(\mid u - v \mid\), forming a vector of size \(3n\). This is passed through a fully connected linear layer with weight matrix \(W_t \in \mathbb{R}^{3n \times k}\) before applying softmax \(o = \text{softmax}(W_t [u; v; \mid u - v \mid])\), where \(k\) is the number of output classes (since the SBERT paper focused on NLI, they were entailment, contradiction, and neutral). This projection layer provides the learned transformation before softmax classification. By removing the softmax head at inference time, SBERT reduces similarity computation from \(O(n^2)\) pairwise comparisons to \(O(n)\) independent embedding computations followed by lightweight cosine similarity scoring—enabling massive speedups in retrieval. During training, the softmax classifier makes the model close-ended, restricted to a fixed set of \(k\) output classes (e.g., entailment, contradiction, neutral). In contrast, inference is open-ended: without the softmax constraint, SBERT functions as a general-purpose feature extractor whose embeddings can be compared across unseen categories using cosine similarity, optionally followed by thresholding on the score \(\text{sim}(u, v) = \frac{u \cdot v}{\mid u \mid \mid v \mid}\) for binary decisions (e.g., “similar” vs. “not similar”).

- Although the original SBERT paper did not employ it, this triplet framework can be extended to Multiple Negatives Ranking Loss (MNRL), where each batch provides multiple implicit negatives for every anchor–positive pair. MNRL improves efficiency by leveraging all non-matching pairs within a batch as negatives, making training more stable and scalable for large datasets.

- Efficiency in Generating Sentence Embeddings or Similarity Tasks: In the standard BERT model, sentence embeddings are generated using the

[CLS]vector from the last layer, which performs poorly for semantic similarity (correlations as low as 0.29 on STS tasks). In contrast, SBERT dramatically improves both accuracy and computational efficiency: semantic similarity searches that would take ~65 hours with BERT can be done in about 5 seconds with SBERT. - Applicability: While BERT excels at tasks requiring token-level understanding (e.g., named entity recognition, question answering), Sentence Transformers are optimized for semantic similarity, clustering, and retrieval tasks.

- The left half of the following figure (source) shows the SBERT architecture with the classification objective function, e.g., for fine-tuning on SNLI dataset. The two BERT networks have tied weights (siamese network structure).

- This figure illustrates the training phase, where two tied-weight BERT encoders process sentences A and B to produce embeddings \(u\) and \(v\). These embeddings are concatenated with their element-wise absolute difference \(\mid u - v \mid\) and passed through a linear projection layer \(W_t\) before a softmax classifier predicts relational labels such as entailment or contradiction. The softmax layer is critical during training because it provides a supervised learning signal (with discrete classification labels) that guides the model to map semantically related sentences close together in embedding space.

- The right half of the following figure (source) shows the SBERT architecture during inference, for example, to compute similarity scores. This architecture is also used with the regression objective function.

- This figure depicts the inference phase, where the trained encoders are used without the softmax classification head. Instead, embeddings are generated independently for each sentence and compared using cosine similarity, optionally followed by thresholding to make binary similarity decisions.

- The removal of the softmax layer is essential because, if retained, it would require concatenating pairs of embeddings and performing a new forward pass for each pair—reintroducing the \(O(n^2)\) cost of cross-encoding. Without the softmax layer, embeddings can be computed once per sentence (offline or on-demand), allowing fast vector-based retrieval and comparison. In other words, omitting the softmax during inference enables the key property that makes SBERT efficient: sentence embeddings become independent representations that can be precomputed and compared directly using cosine similarity, without needing joint inference over pairs.

- In summary, while BERT is a general-purpose contextual language model, Sentence Transformers like SBERT are optimized for semantic comparison at the sentence level, producing dense, meaningful embeddings well-suited for similarity-based tasks.

Training Process for Sentence Transformers vs. Token-Level Embedding Models

-

Sentence Transformers are trained differently from token-level models such as BERT. Their process focuses on aligning sentence meanings rather than predicting masked words.

- Model Architecture: SBERT builds on pretrained BERT or RoBERTa models by adding a pooling layer that converts token-level outputs into a single sentence embedding.

- Training Data: SBERT is fine-tuned on Natural Language Inference (NLI) datasets like SNLI and MultiNLI, containing hundreds of thousands of labeled sentence pairs that capture semantic relations.

- Training Objectives:

- Classification Objective: Concatenates embeddings of two sentences \((u, v)\) with their element-wise absolute difference \(\mid u - v \mid\), projects the resulting \(3n\)-dimensional vector through a linear layer \(W_t \in \mathbb{R}^{3n \times k}\), and applies softmax to obtain class probabilities. This setup makes training close-ended, restricted to the predefined NLI labels, whereas inference is open-ended, since embeddings can later be compared beyond those classes using cosine similarity and thresholding.

- Regression Objective: Minimizes mean-squared error between cosine similarity of embeddings and human-annotated similarity scores.

- Triplet Objective: Minimizes the margin between anchor–positive and anchor–negative pairs, ensuring semantically close sentences are closer in embedding space. Although the original paper did not use it, this triplet loss can naturally extend to Multiple Negatives Ranking Loss (MNRL), which treats every non-matching sentence in the same batch as a negative sample—improving data efficiency and convergence for large-scale contrastive learning.

- Pooling and Representation: The final sentence embedding is typically the mean of all token embeddings from the last hidden layer, which captures overall sentence meaning better than using only the

[CLS]token. - Efficiency Gains: SBERT reduces the number of required pairwise comparisons from \(O(n^2)\) to \(O(n)\), since sentence embeddings can be precomputed and compared using cosine similarity. This makes it suitable for large-scale applications like semantic search or clustering.

- Evaluation and Performance: SBERT achieves state-of-the-art performance on multiple STS benchmarks, outperforming models like InferSent and Universal Sentence Encoder by significant margins (average correlation improvements of 5–12 points).

-

Practical Impact on Retrieval Systems: SBERT’s dual-encoder setup—where sentences are encoded independently and compared via cosine similarity—became the cornerstone of dense retrieval. Removing the softmax layer in inference is precisely what enables offline precomputation and real-time similarity search across massive corpora. This innovation allowed embedding-based retrieval systems, approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search, and RAG pipelines to become scalable and efficient at industrial scale.

-

In summary, Sentence-BERT extends BERT with architecture and training modifications that produce semantically rich, scalable, and efficient sentence representations suitable for similarity and clustering tasks.

Applying Sentence Transformers for RAG

- Now, let’s look into why sentence transformers are the numero uno choice of models to generate embeddings for RAG.

- RAG leverages Sentence Transformers for their ability to understand and compare the semantic content of sentences. This integration is particularly useful in scenarios where the model needs to retrieve relevant information before generating a response. Here’s how Sentence Transformers are useful in a RAG setting:

- Improved Document Retrieval: Sentence Transformers are trained to generate embeddings that capture the semantic meaning of sentences. In a RAG setting, these embeddings can be used to match a query (like a user’s question) with the most relevant documents or passages in a database. This is critical because the quality of the generated response often depends on the relevance of the retrieved information.

- Efficient Semantic Search: Traditional keyword-based search methods might struggle with understanding the context or the semantic nuances of a query. Sentence Transformers, by providing semantically meaningful embeddings, enable more nuanced searches that go beyond keyword matching. This means that the retrieval component of RAG can find documents that are semantically related to the query, even if they don’t contain the exact keywords.

- Contextual Understanding for Better Responses: By using Sentence Transformers, the RAG model can better understand the context and nuances of both the input query and the content of potential source documents. This leads to more accurate and contextually appropriate responses, as the generation component of the model has more relevant and well-understood information to work with.

- Scalability in Information Retrieval: Sentence Transformers can efficiently handle large databases of documents by pre-computing embeddings for all documents. This makes the retrieval process faster and more scalable, as the model only needs to compute the embedding for the query at runtime and then quickly find the closest document embeddings.

- Enhancing the Generation Process: In a RAG setup, the generation component benefits from the retrieval component’s ability to provide relevant, semantically-rich information. This allows the language model to generate responses that are not only contextually accurate but also informed by a broader range of information than what the model itself was trained on.

- In summary, Sentence Transformers enhance the retrieval capabilities of RAG models with LLMs by enabling more effective semantic search and retrieval of information. This leads to improved performance in tasks that require understanding and generating responses based on large volumes of text data, such as question answering, chatbots, and information extraction.

Retrieval

- Retrieval is the core mechanism that enables RAG systems to ground language model outputs in external knowledge by selecting a small, relevant subset of documents or passages from a large corpus to condition generation.

- Lexical, semantic, and hybrid retrieval methods define how queries are mapped to candidate context, directly influencing what information the language model can and cannot use when generating an answer.

- A solid understanding of retrieval techniques is critical for RAG because retrieval failures (missing key facts, retrieving irrelevant context, or violating constraints) propagate downstream and manifest as hallucinations, inaccuracies, or unsafe outputs during generation.

- A detailed discourse of retrieval (also known as the information retrieval problem) is available in our Search primer.

Lexical Retrieval

- Lexical retrieval, also referred to as sparse retrieval, term-based retrieval, or keyword-based retrieval, is the classical foundation of information retrieval systems. It operates purely on observable text signals, relying on exact token matches between a query and documents. Relevance is estimated using statistical properties of terms within documents and across the corpus, without attempting to model meaning or intent.

- At its core, lexical retrieval assumes that relevance correlates with how frequently and distinctively query terms appear in a document.

Core assumptions

-

Lexical retrieval is deterministic, interpretable, and highly efficient at scale because of the following assumptions:

- Words are treated as discrete symbols (tokens).

- Matching is based on an exact match overlap.

- Importance is inferred from distributional statistics, not semantics.

- Query intent is approximated by the literal terms provided.

TF-IDF (Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency)

-

TF-IDF is one of the earliest and most influential scoring schemes in information retrieval. It decomposes relevance into two components:

-

Term Frequency (TF): Measures how often a term appears in a document. The intuition is that repeated mentions indicate topical relevance.

-

Inverse Document Frequency (IDF): Downweights terms that appear frequently across the corpus, under the assumption that common words carry less discriminative power.

-

-

A standard formulation is:

\[\text{TF-IDF}(t, d) = \text{TF}(t, d) \cdot \log\left(\frac{N}{\text{DF}(t)}\right)\]-

where:

- \(t\) is a term,

- \(d\) is a document,

- \(N\) is the total number of documents,

- \(\text{DF}(t)\) is the number of documents containing \(t\).

-

Strengths of TF-IDF

- Simple and fast to compute.

- Strong baseline for keyword-heavy queries.

- Fully interpretable scoring.

- Requires no training data.

Limitations of TF-IDF

-

These limitations motivated more refined probabilistic ranking functions.

- Linear growth of TF causes term repetition to dominate scores.

- No document length normalization.

- Treats all term positions equally.

- Performs poorly on long documents and verbose queries.

- Fails completely on synonymy and paraphrasing.

BM25 (Best Matching 25)

-

BM25 is a probabilistic retrieval model that improves upon TF-IDF by addressing its key weaknesses. It introduces two critical refinements:

-

Term frequency saturation: Additional occurrences of a term provide diminishing returns rather than linear gains.

-

Document length normalization: Longer documents are normalized to prevent unfair advantage due to sheer volume of text.

-

-

A common BM25 formulation is:

\[\text{BM25}(q, d) = \sum_{t \in q} \text{IDF}(t) \cdot \frac{f(t,d) \cdot (k_1 + 1)} {f(t,d) + k_1 \cdot \left(1 - b + b \cdot \frac{|d|}{\text{avgdl}}\right)}\]-

where:

- \(f(t,d)\) is the frequency of term \(t\) in document \(d\),

- \(\mid d \mid\) is the document length,

- \(\text{avgdl}\) is the average document length,

- \(k_1\) controls TF saturation (typically \(1.2 \le k_1 \le 2.0\)),

- \(b\) controls length normalization (typically \(b \approx 0.75\)).

-

Why BM25 outperforms TF-IDF

-

BM25 remains the default lexical ranking function in most production search engines. It outperforms TF-IDF along the following dimensions:

- Prevents term stuffing from dominating rankings.

- Fairly compares short and long documents.

- More stable across heterogeneous corpora.

- Empirically strong across many domains without tuning.

Operational characteristics of lexical retrieval

-

Performance and scalability:

- Sub-millisecond scoring per document.

- Efficient inverted index structures.

- Scales to billions of documents.

-

Determinism:

- Identical inputs always produce identical rankings.

- No stochastic components or model drift.

-

Explainability:

- Rankings can be justified via term overlap and weights.

- Essential for regulated or high-stakes systems.

Advantages

- Extremely fast and resource-efficient.

- Robust to rare, technical, or newly introduced terms.

- Guarantees recall for exact matches.

- Transparent scoring behavior.

- Works exceptionally well for:

- Identifiers (product IDs, SKUs, error codes, etc.)

- Entity names (proper nouns, etc.)

- Dates (timestamps, ranges, etc.)

- Abbreviations (e.g., API, HTTP, JWT, etc.)

- Domain-specific jargon (e.g., medicine names, chemical compounds, etc.)

- Legal clauses (e.g., “Section 3.2.1”, etc.) and citations (e.g., “17 U.S.C. § 512”, etc.)

- Short or underspecified queries

Limitations

- Lexical retrieval limitations are structural, not implementation flaws, and they are the primary reason semantic and hybrid retrieval methods emerged:

- No understanding of meaning or intent.

- Cannot match synonyms or paraphrases.

- Sensitive to vocabulary mismatch.

- Brittle for natural language questions.

- Poor recall for descriptive or conversational queries.

Semantic Retrieval

-

Semantic retrieval, also commonly referred to as dense retrieval, neural retrieval, or embedding-based retrieval, is a modern approach to information retrieval that attempts to model the meaning and intent behind queries and documents rather than relying on exact lexical overlap.

-

Instead of treating text as discrete symbols, semantic retrieval represents text as continuous vectors in a high-dimensional space. Relevance is determined by geometric proximity in this space, under the assumption that semantically similar texts lie close to each other.

Core idea

-

Semantic retrieval reframes search as a similarity problem in vector space:

- Queries and documents are encoded into dense vectors.

- Similarity between vectors approximates semantic relatedness.

- Retrieval becomes a nearest-neighbor search problem.

-

A common similarity measure is cosine similarity:

\[\text{cosine_sim}(q, d) = \frac{\vec{q} \cdot \vec{d}} {\mid\vec{q}\mid \mid\vec{d}\mid}\]-

where:

- \(\vec{q}\) is the query embedding,

- \(\vec{d}\) is the document embedding.

-

Vector encoding

- Encoder models:

-

Queries and documents are passed through neural encoders, typically based on transformer architectures. Common encoder types include:

- Dual encoders (bi-encoders)

- Sentence transformers

- Domain-specific fine-tuned encoders

-

In most production systems, queries and documents are encoded independently to allow precomputation of document embeddings.

-

- Training signal:

-

Encoders are trained using contrastive objectives that:

- Pull relevant query–document pairs closer

- Push irrelevant pairs farther apart

-

A simplified contrastive loss can be expressed as:

\[\mathcal{L} = -\log\frac{\exp(\text{sim}(q, d^+))}{\exp(\text{sim}(q, d^+)) + \sum_{d^-} \exp(\text{sim}(q, d^-))}\]- where \(d^+\) is a relevant document and \(d^-\) are negatives.

-

- Representation properties:

-

Good semantic embeddings capture:

- Synonymy and paraphrasing

- Conceptual similarity

- Contextual meaning

- Cross-lingual alignment (in multilingual models)

-

Semantic matching and retrieval

-

Once embeddings are computed:

- Documents are indexed in a vector index.

- At query time, the query embedding is generated.

- Approximate nearest neighbor search retrieves the top \(K\) closest document vectors.

-

This enables matches even when there is zero keyword overlap between query and document.

Approaches

- Let’s look at three different types of retrieval: standard, sentence window, and auto-merging. Each of these approaches has specific strengths and weaknesses, and their suitability depends on the requirements of the RAG task, including the nature of the dataset, the complexity of the queries, and the desired balance between specificity and contextual understanding in the responses.

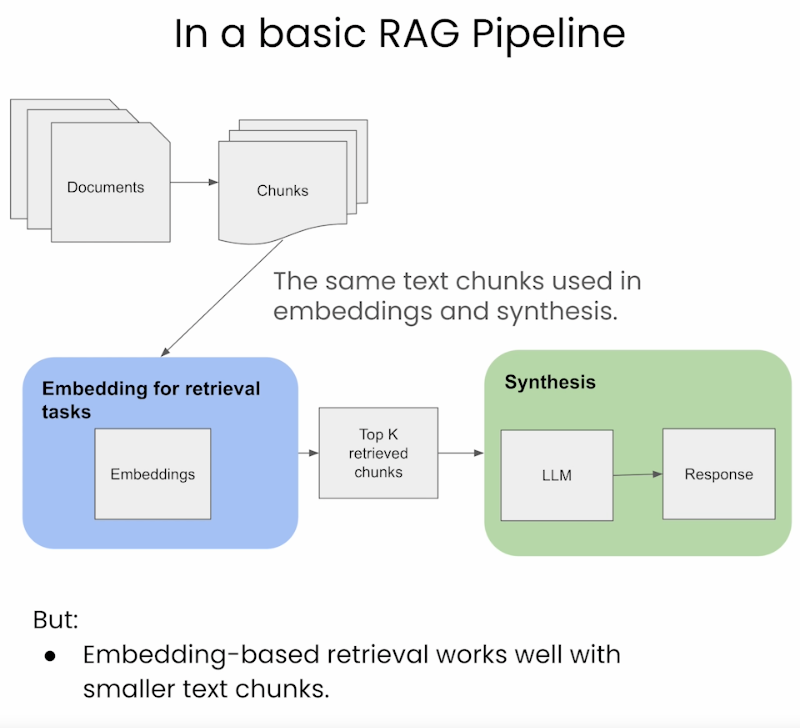

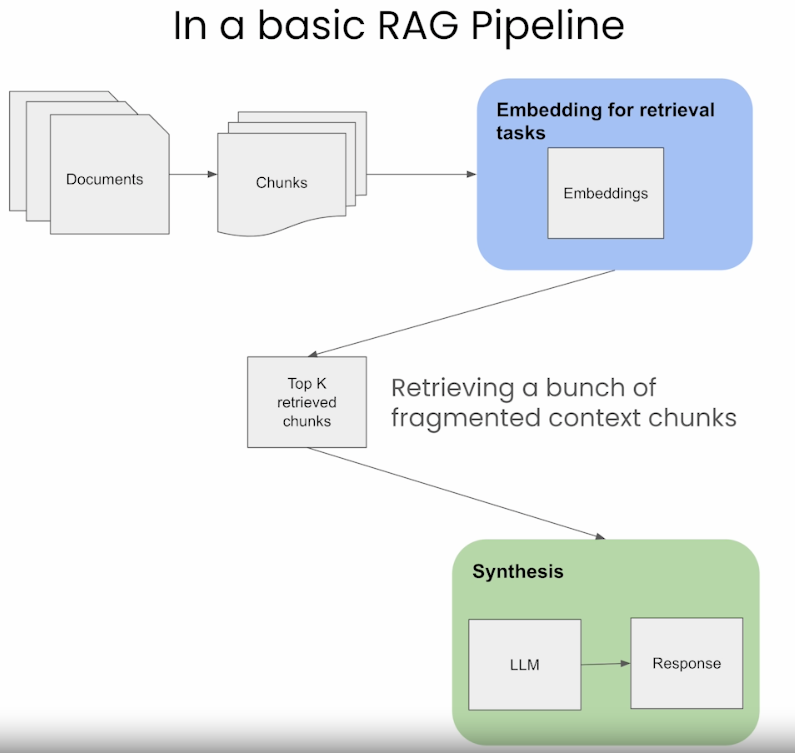

Standard/Naive approach

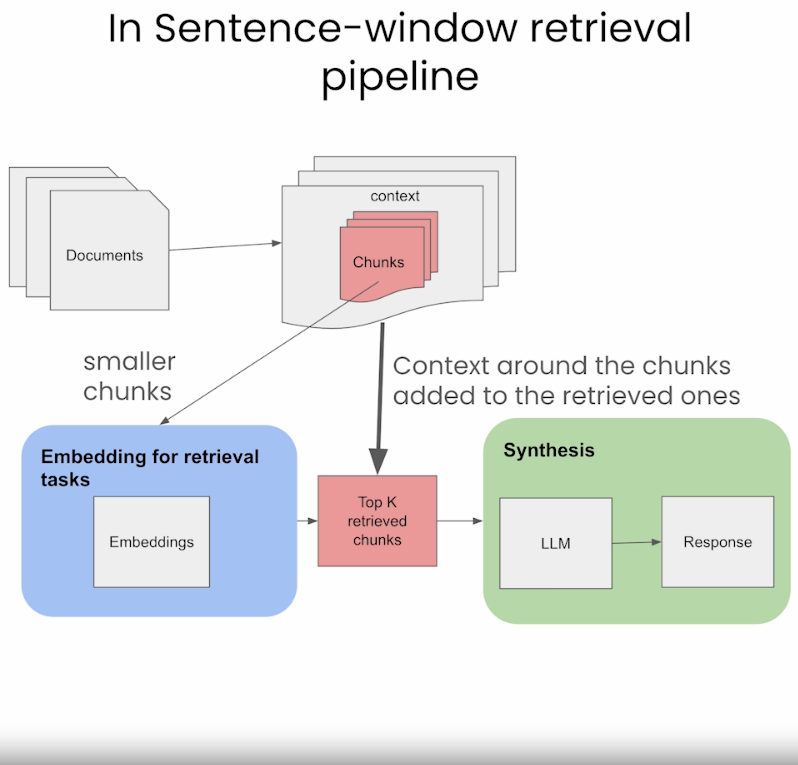

- As we see in the image below (source), the standard pipeline uses the same text chunk for indexing/embedding as well as the output synthesis.

-

In the context of RAG, the advantages and disadvantages of the three approaches are as follows:

-

Advantages:

- Simplicity and Efficiency: This method is straightforward and efficient, using the same text chunk for both embedding and synthesis, simplifying the retrieval process.

- Uniformity in Data Handling: It maintains consistency in the data used across both retrieval and synthesis phases.

-

Disadvantages:

- Limited Contextual Understanding: LLMs may require a larger window for synthesis to generate better responses, which this approach may not adequately provide.

- Potential for Suboptimal Responses: Due to the limited context, the LLM might not have enough information to generate the most relevant and accurate responses.

Sentence-Window Retrieval / Small-to-Large Retrieval

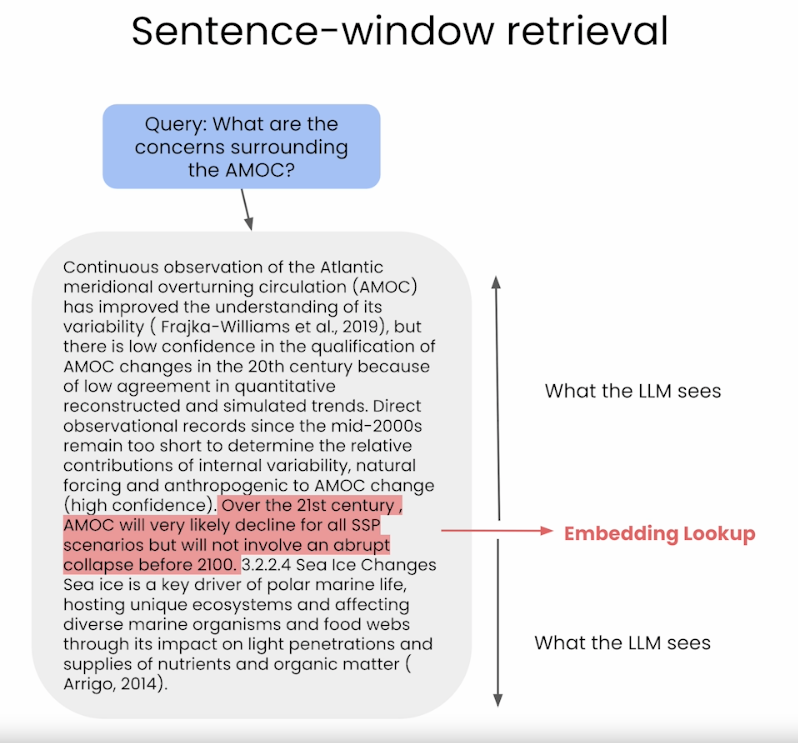

- The sentence-window approach breaks down documents into smaller units, such as sentences or small groups of sentences.

- It decouples the embeddings for retrieval tasks (which are smaller chunks stored in a Vector DB), but for synthesis it adds back in the context around the retrieved chunks, as seen in the image below (source).

- During retrieval, we retrieve the sentences that are most relevant to the query via similarity search and replace the sentence with the full surrounding context (using a static sentence-window around the context, implemented by retrieving sentences surrounding the one being originally retrieved) as shown in the figure below (source).

-

Advantages:

- Enhanced Specificity in Retrieval: By breaking documents into smaller units, it enables more precise retrieval of segments directly relevant to a query.

- Context-Rich Synthesis: It reintroduces context around the retrieved chunks for synthesis, providing the LLM with a broader understanding to formulate responses.

- Balanced Approach: This method strikes a balance between focused retrieval and contextual richness, potentially improving response quality.

-

Disadvantages:

- Increased Complexity: Managing separate processes for retrieval and synthesis adds complexity to the pipeline.

- Potential Contextual Gaps: There’s a risk of missing broader context if the surrounding information added back is not sufficiently comprehensive.

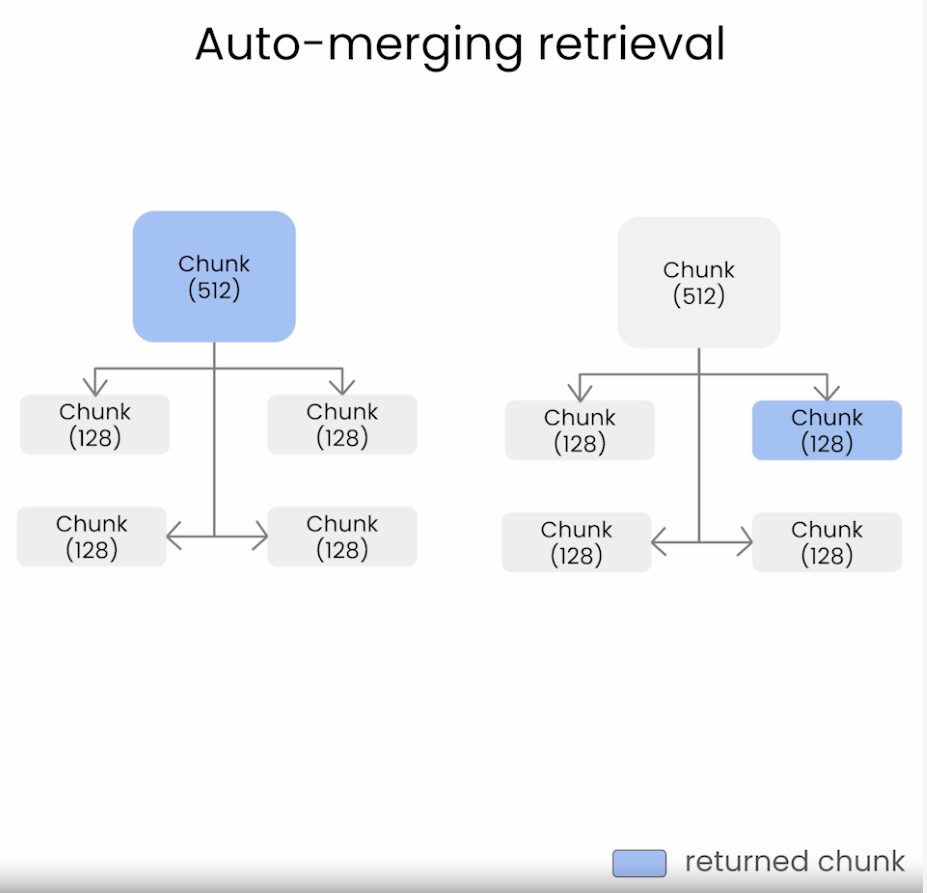

Auto-merging Retriever / Hierarchical Retriever

- The image below (source), illustrates how auto-merging retrieval can work where it doesn’t retrieve a bunch of fragmented chunks as would happen with the naive approach.

- The fragmentation in the naive approach would be worse with smaller chunk sizes as shown below (source).

- Auto-merging retrieval aims to combine (or merge) information from multiple sources or segments of text to create a more comprehensive and contextually relevant response to a query. This approach is particularly useful when no single document or segment fully answers the query but rather the answer lies in combining information from multiple sources.

- It allows smaller chunks to be merged into bigger parent chunks. It does this via the following steps:

- Define a hierarchy of smaller chunks linked to parent chunks.

- If the set of smaller chunks linking to a parent chunk exceeds some threshold (say, cosine similarity), then “merge” smaller chunks into the bigger parent chunk.

-

The method will finally retrieve the parent chunk for better context.

-

Advantages:

- Comprehensive Contextual Responses: By merging information from multiple sources, it creates responses that are more comprehensive and contextually relevant.

- Reduced Fragmentation: This approach addresses the issue of fragmented information retrieval, common in the naive approach, especially with smaller chunk sizes.

- Dynamic Content Integration: It dynamically combines smaller chunks into larger, more informative ones, enhancing the richness of the information provided to the LLM.

-

Disadvantages:

- Complexity in Hierarchy and Threshold Management: The process of defining hierarchies and setting appropriate thresholds for merging is complex and critical for effective functioning.

- Risk of Over-generalization: There’s a possibility of merging too much or irrelevant information, leading to responses that are too broad or off-topic.

- Computational Intensity: This method might be more computationally intensive due to the additional steps in merging and managing the hierarchical structure of text chunks.

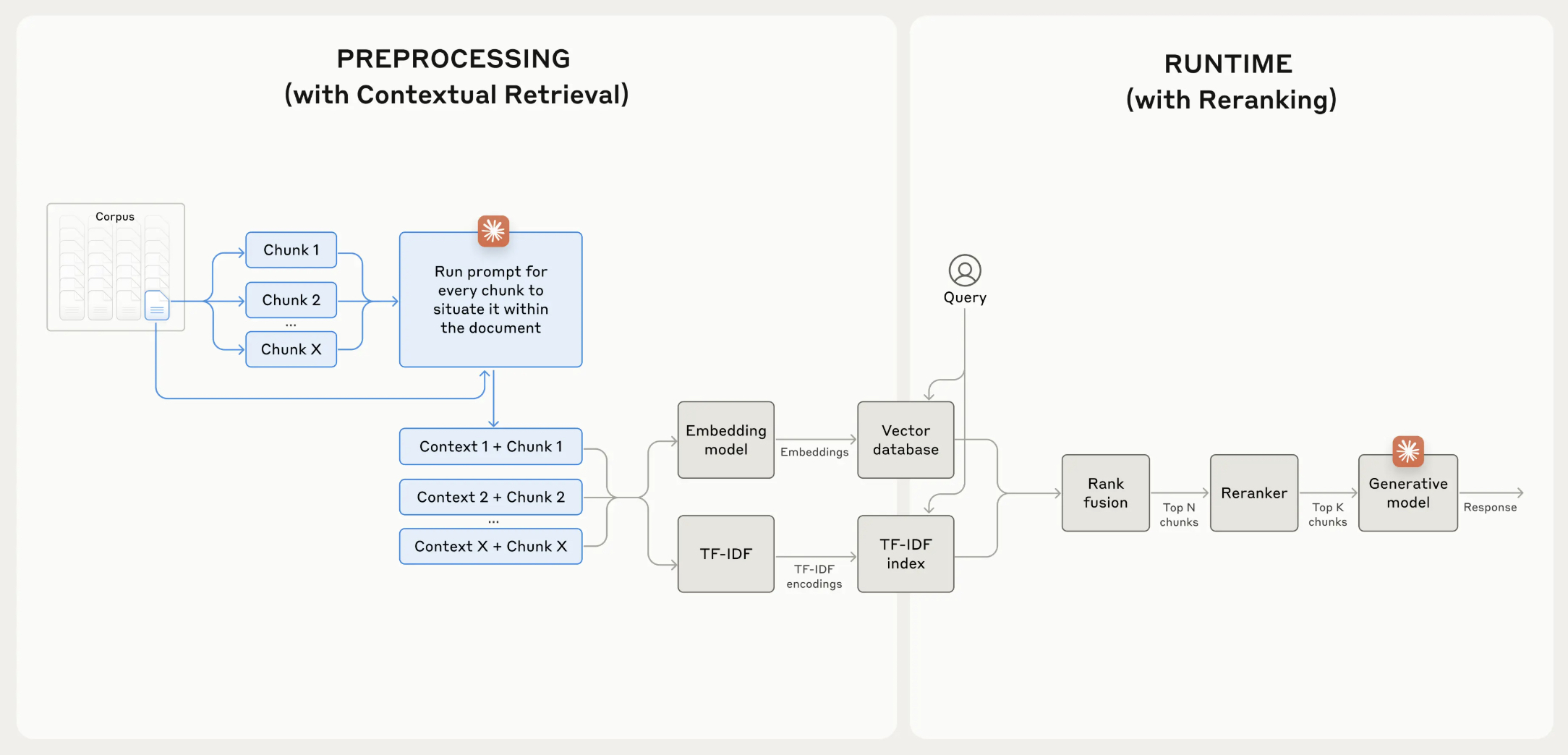

Contextual Retrieval

- For LLMs to deliver relevant and accurate responses, they must retrieve the right information from a knowledge base. Traditional RAG improves model accuracy by fetching relevant text chunks and appending them to the prompt. However, such methods often remove crucial context when encoding information, leading to failed retrievals and suboptimal outputs.

- Contextual Retrieval, introduced by Anthropic, is an advanced technique designed to improve this process by ensuring that retrieved chunks maintain their original context. It employs contextual embeddings – embeddings that incorporate chunk-specific background information and contextual BM25 – an enhanced BM25 ranking that considers the broader document context.

-

By prepending contextual metadata to each document chunk before embedding, Contextual Retrieval significantly enhances search accuracy. This approach reduces failed retrievals by 49% and, when combined with re-ranking, by 67%.

- Why Context Matters in Retrieval:

- Traditional RAG solutions divide documents into small chunks for efficient retrieval. However, these fragments often lose critical context. For example, the statement “The company’s revenue grew by 3% over the previous quarter” lacks information about which company or quarter it refers to. Contextual Retrieval solves this by embedding relevant metadata into each chunk.

- Implementation of Contextual Retrieval:

- To implement Contextual Retrieval, a model like Claude 3 Haiku can generate concise context for each chunk. This context is then prepended before embedding and indexing, ensuring more precise retrieval. Developers can automate this process at scale using specialized retrieval pipelines.

- Prompt Used for Contextual Retrieval:

- Anthropic’s method involves using Claude to generate a short, document-specific context for each chunk using the following prompt:

<document> </document> Here is the chunk we want to situate within the whole document: <chunk> </chunk> Please give a short, succinct context to situate this chunk within the overall document for the purposes of improving search retrieval of the chunk. Answer only with the succinct context and nothing else. - This process automatically generates a concise contextualized description that is prepended to the chunk before embedding and indexing.

- Anthropic’s method involves using Claude to generate a short, document-specific context for each chunk using the following prompt:

- Combining Contextual Retrieval with Re-ranking:

- For maximum performance, Contextual Retrieval can be paired with re-ranking models, which filter and reorder retrieved chunks based on their relevance. This additional step enhances retrieval precision, ensuring only the most relevant chunks are passed to the LLM.

- The following flowchart from Anthropic’s blog shows the combined contextual retrieval and re-ranking stages which seek to maximize retrieval accuracy.

- Key Takeaways:

- Contextual Embeddings improve retrieval accuracy by preserving document meaning.

- BM25 + Contextualization enhances exact-match retrieval.

- Combining Contextual Retrieval with re-ranking further boosts retrieval effectiveness.

- Developers can implement Contextual Retrieval using prompt-based preprocessing and automated pipelines.

- With Contextual Retrieval, LLM-powered knowledge systems can achieve greater accuracy, scalability, and relevance, unlocking new levels of performance in real-world applications.

Using Approximate Nearest Neighbors (ANN) for Retrieval

-

The next step is to consider which Approximate Nearest Neighbors (ANN) algorithm and library to choose for large-scale vector similarity search in retrieval systems. ANN is preferred over exact nearest neighbor search because:

- Exact search scales linearly with corpus size and becomes prohibitively slow and expensive for large embedding collections.

- ANN trades a small, controllable loss in recall for orders-of-magnitude improvements in latency and throughput.

- Modern ANN methods are designed to meet strict production constraints (low latency, bounded memory, high QPS), which are critical for real-time RAG pipelines.

- A useful way to compare and select an appropriate ANN approach is to reference ANN-Benchmarks, which provides standardized evaluations of different algorithms across accuracy, latency, and resource trade-offs.

- A detailed discourse on the concept of ANN can be found in our ANN primer.

Advantages of Semantic Retrieval

- Strong handling of paraphrases and synonyms.

- Robust to vocabulary mismatch.

- Supports natural language and conversational queries.

- Effective for long, descriptive queries.

- Often works across languages without explicit translation.

- Recovers relevant content missed by lexical methods.

Challenges

-

Computational cost:

- Embedding generation is expensive relative to lexical scoring.

- Nearest neighbor search is more complex than inverted index lookup.

-

Approximation trade-offs:

- Vector search typically uses approximate algorithms.

- Recall may be sacrificed for latency at scale.

-

Model dependence:

- Retrieval quality depends heavily on training data.

- Domain mismatch can degrade performance.

- Biases in training data propagate into retrieval results.

-

Maintenance complexity:

- Document embeddings must be recomputed when:

- The corpus changes significantly

- The model is updated

- Versioning embeddings and models adds operational overhead.

- Document embeddings must be recomputed when:

-

Precision issues:

- Semantic similarity can over-generalize.

- Exact constraints, identifiers, or negations may be missed.

- Rare or newly introduced terms may not be well represented.

Use-cases where semantic retrieval excels

- Exploratory or research-oriented search.

- Natural language question answering.

- Knowledge discovery and recall-heavy tasks.

- User-facing search with ambiguous or verbose queries.

Use-cases where semantic retrieval struggles

-

These strengths and weaknesses are complementary to lexical retrieval, which is why semantic retrieval is rarely deployed alone in high-reliability systems. Specifically the areas where semantic search struggles are as follows:

- Queries dominated by symbols, codes, or IDs.

- Legal, medical, or compliance-sensitive text requiring exact wording.

- Short, underspecified queries with little context.

- Scenarios demanding deterministic, explainable rankings.

Hybrid Retrieval (Lexical + Semantic)

-

Hybrid retrieval combines lexical (sparse) and semantic (dense) retrieval to leverage the complementary strengths of both approaches. The core motivation is simple: real-world queries simultaneously contain exact terms that must be respected and implicit intent that must be inferred.

-

A hybrid retrieval system combines the strengths of lexical and semantic methods to deliver more accurate and robust results by reducing the likelihood that either system’s blind spots dominate the final ranking.

-

Hybrid systems are designed to minimize worst-case failure modes by ensuring that neither exact matching nor semantic understanding is relied on exclusively.

Why hybrid retrieval is necessary

-

Lexical and semantic retrieval fail in opposite ways:

- Lexical retrieval fails when vocabulary mismatch occurs.

- Semantic retrieval fails when exact wording, identifiers, or constraints matter.

-

Hybrid retrieval exists to ensure:

- Exact matches are never lost.

- Semantic relevance is still captured.

- Recall and precision remain stable across query types.

-

In practice, hybrid retrieval is not a single algorithm but a family of architectures.

Common hybrid retrieval architectures

-

Two-stage hybrid retrieval: Lexical retrieval is used first to generate a high-recall candidate set, which is then reranked by a semantic model. This design prioritizes efficiency and recall safety while allowing deep semantic reasoning to operate only where it matters.

-

Parallel hybrid retrieval with fusion: Lexical and semantic retrievers run independently over the corpus, and their results are merged using score-based or rank-based fusion methods. This approach treats lexical and semantic signals as peers rather than stages in a pipeline.

-

Native hybrid scoring: Some systems integrate sparse and dense signals directly into a single retrieval model or query interface, blending term-based and embedding-based evidence during initial retrieval rather than combining results afterward.

The dominant production architecture: Lexical retrieval + Semantic re-ranking

-

The most common hybrid architecture is a two-stage pipeline:

- Candidate generation (lexical):

-

A lexical retriever (typically BM25) retrieves the top \(K\) candidates based on exact term overlap.

-

Typical values:

- \[K \in [100, 1000]\]

- Chosen to maximize recall while keeping downstream cost manageable

-

- Semantic re-ranking (dense or cross-encoder):

- Semantic re-ranking models aim to improve the ordering of retrieved documents by more accurately modeling relevance between a query and a small candidate set.

- In practice, these models are used after an initial retrieval step and can be grouped both by how they encode query–document interactions and by the type of signals they incorporate (semantic, instructional, or metadata-driven).

- Candidate generation (lexical):

-

Conceptually:

\[\text{Results} = \text{Rerank}_{\text{semantic}} \big( \text{BM25}(\text{Docs}) \big)\] -

This approach dominates because of its efficiency, recall-safety, easy of explainability, and compatibility with existing search infrastructure.

Parallel hybrid retrieval and score fusion

- An alternative approach runs lexical and semantic retrieval independently, then fuses their rankings. This approach is common when re-ranking is too expensive or when vector databases expose native hybrid querying.

Linear score fusion

\[\text{score}(d) = \alpha \cdot \text{BM25}(d) + (1 - \alpha) \cdot \text{sim}_{\text{semantic}}(d)\]-

Challenges:

- Scores must be normalized

- Sensitive to scaling differences

- Requires tuning \(\alpha\)

Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF)

-

One of the most popular and robust fusion techniques used in hybrid retrieval is Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF). RRF merges the rankings from different retrieval models (for example, BM25 and a neural retriever) by assigning higher scores to documents that consistently rank well across systems, rather than relying on raw scores.

-

RRF operates purely on rank positions, making it insensitive to score scale (i.e., it lacks the need for normalization unlike linear score fusion), distribution, or calibration differences between retrieval methods.

-

How RRF works:

- Each retrieval system independently produces a ranked list of documents.

- Each document receives a contribution based on its rank position in each list.

-

Contributions are summed to produce a final fusion score.

-

The RRF scoring function is:

\[\text{RRF Score}(d) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{1}{k + \text{rank}_i(d)}\]-

where:

- \(d\) is the document,

- \(\text{rank}_i(d)\) is the rank position of document \(d\) in the \(i^{\text{th}}\) ranked list,

- \(k\) is a smoothing constant (typically set to 60),

- \(n\) is the number of retrieval systems.

-

-

The constant \(k\) ensures that:

- Top-ranked documents dominate the contribution

- Differences among lower-ranked documents are compressed

- Noise from deep rankings does not overwhelm the fusion

-

Intuition behind RRF:

- The intuition behind RRF being especially well suited for hybrid lexical–semantic retrieval is as follows:

- Documents that appear near the top in multiple rankings are strongly favored.

- A document that ranks moderately well in several systems often beats one that ranks extremely well in only one.

- Systems with very different scoring behavior can still be combined reliably.

- The intuition behind RRF being especially well suited for hybrid lexical–semantic retrieval is as follows:

-

Example:

-

Suppose two retrieval systems return the following output results for a query:

- BM25:

[DocA, DocB, DocC, DocD, DocE] - Neural Retriever:

[DocF, DocC, DocA, DocG, DocB]

- BM25:

- We use \(k = 60\).

-

Note that if a document does not appear at a output of a retriever, it contributes \(0\) from that list.

-

RRF scores are computed as follows:

-

DocA (Rank 1 in BM25, rank 3 in Neural Retriever):

\[\text{RRF}(\text{DocA}) = \frac{1}{60 + 1} + \frac{1}{60 + 3} = \frac{1}{61} + \frac{1}{63} \approx 0.01639 + 0.01587 = 0.03226\] -