Primers • OpenAI o1

- Overview

- Test-time Compute: Shifting Focus to Inference Scaling

- Test Results

- Limitations

- Use-Cases of OpenAI o1

- Pricing and Accessibility

- Safety and Advancements

- Deployment Patterns for o1 using Dynamic Task Routing

- Conclusion

- Related Papers

- Let’s Verify Step by Step

- Scaling LLM Test-Time Compute Optimally can be More Effective than Scaling Model Parameters

- STaR: Self-Taught Reasoner: Bootstrapping Reasoning With Reasoning

- Quiet-STaR: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Think Before Speaking

- Large Language Monkeys: Scaling Inference Compute with Repeated Sampling

- Learn Beyond The Answer: Training Language Models with Reflection for Mathematical Reasoning

- Agent Q: Advanced Reasoning and Learning for Autonomous AI Agents

- V-STaR: Training Verifiers for Self-Taught Reasoners

- Improve Mathematical Reasoning in Language Models by Automated Process Supervision

- Chain-of-Thought Reasoning without Prompting

- Training Language Models to Self-Correct via Reinforcement Learning

- Further Reading

- References

- Citation

Overview

- OpenAI’s o1 models are a leap forward in reasoning and problem-solving capabilities for complex tasks, especially in the domains of STEM, coding, and scientific reasoning. The o1 series introduces a novel training method based on reinforcement learning (RL) combined with chain-of-thought reasoning, allowing the model to “think” through problems before producing an output. This deeper reasoning approach significantly enhances the model’s performance on tasks requiring logic, math, and technical expertise.

- The key models in this series include

o1-preview, a high-performance reasoning model, ando1-mini, a cost-efficient alternative designed for faster performance and lower computational costs, especially for coding and technical reasoning tasks.o1-minimodel offers a faster, more efficient alternative too1-preview, optimizing for cost-effectiveness and speed while sacrificing some breadth of knowledge. This makes it ideal for developers focused on coding and technical tasks. Meanwhile,o1-previewexcels at handling more complex reasoning tasks by taking advantage of extended test-time compute.

Key Ideas

- Chain-of-thought reasoning using large-scale RL for improved problem-solving, enabling the model to break down tasks into manageable steps.

- Longer response times, ranging from seconds to minutes, allowing the model to generate more thoughtful and accurate results by producing more internal reasoning tokens (these tokens are hidden from the user but billed).

- The models do not support tool usage, batch calls, or image inputs. They are designed for reasoning-based tasks without relying on external information.

- API access is limited to high-tier users with a minimum $1,000 spend, emphasizing exclusivity for advanced applications.

- Increased output token limits (32,768 for

o1-previewand 65,536 foro1-mini) ensure enough space for reasoning and responses in complex tasks.

Test-time Compute: Shifting Focus to Inference Scaling

- The release of o1 signals a paradigm shift in how test-time/inference-time compute is utilized, marking the most significant change since the foundational Chinchilla scaling law of 2022. While many had predicted a plateau in LLM capabilities by focusing exclusively on training scaling, o1 introduces a breakthrough by highlighting the critical role of inference scaling in overcoming diminishing returns. This shift recognizes the interplay between training and inference curves, rather than relying solely on training compute for improvements.

- No self-improving LLM algorithm has achieved significant gains beyond three iterations. Unlike AlphaGo’s success in using additional compute to extend its performance beyond human-level abilities, no LLM has been able to replicate this in the context of LLM training. However, with the introduction of test-time compute scaling in o1, this may represent a new frontier for AI models, enabling them to solve increasingly complex problems by refining their reasoning in real-time.

- Instead of focusing exclusively on the trade-offs associated with training-time compute, the o1 model emphasizes test-time/inference-time compute, allowing the model to “think” during inference by generating chains of reasoning. Much like AlphaGo’s Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), o1 models simulate various strategies and scenarios during inference to converge on optimal solutions. This strategy marks a key departure from earlier approaches, such as GPT-4o, which relied heavily on large pre-trained models.

Inference Scaling: A New Paradigm

- The key innovation in o1 lies in the interplay between training and inference scaling, recognizing that the two curves must work together. While many AI researchers expected diminishing returns by focusing exclusively on training scaling laws, o1 has shifted the focus to inference scaling, which allows the model to think through tasks during inference by simulating possible solutions. This approach enables o1 to overcome the diminishing returns seen in training alone, leading to significantly enhanced capabilities during inference.

- Unlike earlier models, o1 leverages inference scaling to handle complex reasoning tasks more efficiently. During inference, the model refines its outputs through real-time search, similar to AlphaGo’s approach to gameplay. This search-based refinement allows the model to reach better solutions by rolling out multiple strategies in real-time.

- Below are some of the key ideas in test-time compute:

-

Decoupling Reasoning from Knowledge: The o1 models demonstrate that massive models aren’t necessary for reasoning tasks. In previous models, a large portion of parameters was dedicated to memorizing facts for benchmarks like Trivia QA. However, o1 introduces a smaller, more efficient “reasoning core”, separating reasoning from knowledge. This core can call on external tools (e.g., browser, code verifier) to handle specialized tasks, reducing the need for large pre-trained models and allowing for a reduction in pre-training compute.

-

Inference Scaling and Longer Response Times: o1 models shift a substantial amount of compute to serving inference instead of pre- or post-training. This shift allows the models to generate longer, more detailed reasoning outputs, especially for complex tasks in coding, mathematics, and scientific problem-solving. The extended response times (ranging from several seconds to minutes) allow for deeper reasoning, as the models generate additional internal reasoning tokens during inference, improving overall accuracy and depth.

-

Dynamic Resource Allocation: Leveraging more test-time compute, o1 models can dynamically enhance performance by adjusting computational resources based on task complexity. This contrasts with earlier models like GPT-4o, which had fixed test-time compute limits. By enabling dynamic resource allocation, o1 ensures that more compute is used where necessary, improving performance on tasks that require deeper thought.

-

Data Flywheel Effect: The o1 models have the potential to create a data flywheel by generating search traces during inference. When a correct answer is produced, the search trace becomes a mini dataset of training examples containing both positive and negative rewards. These examples can improve the reasoning core for future iterations of the model, much like how AlphaGo’s value network refined itself through MCTS-generated training data.

The Role of Reinforcement Learning in o1

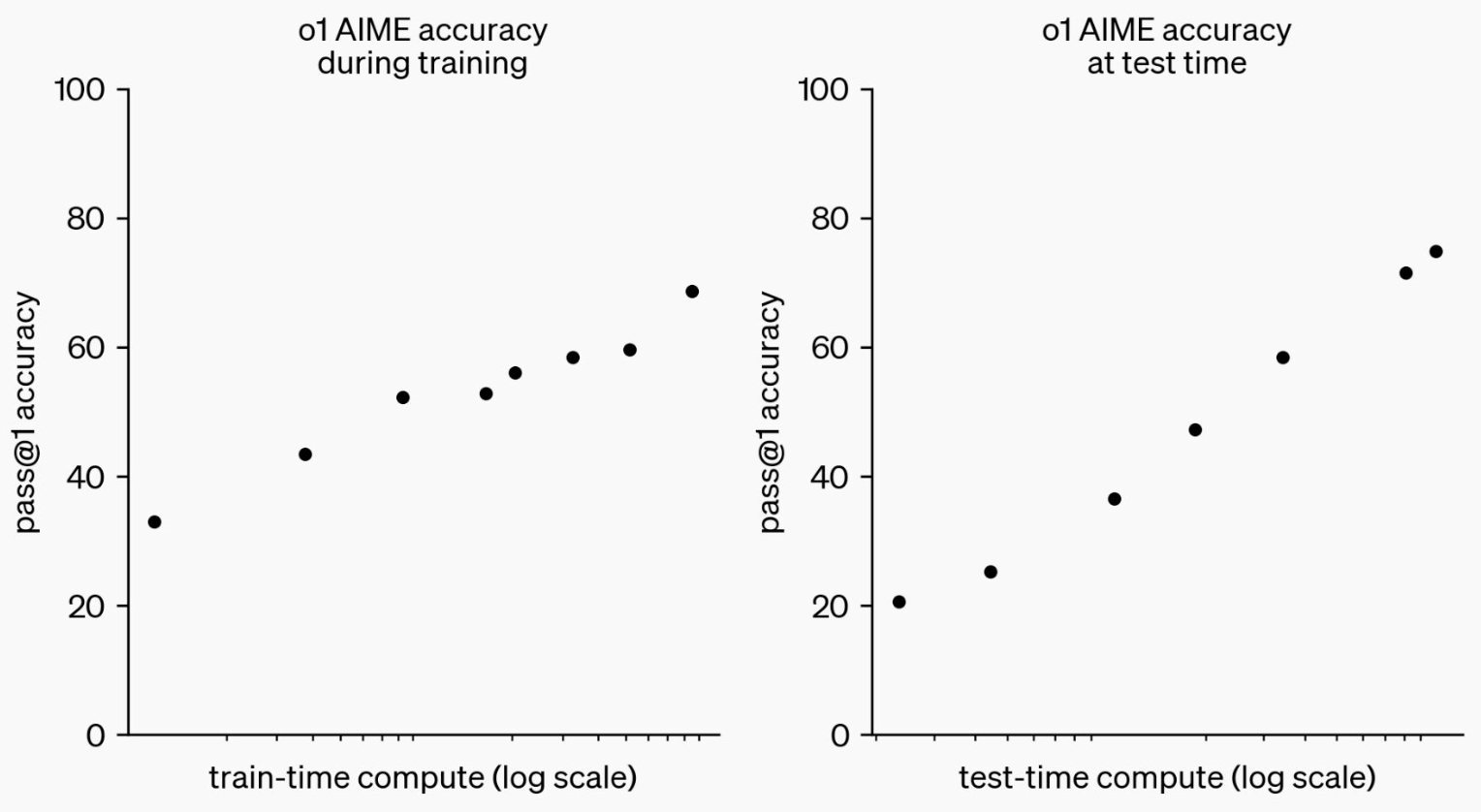

- o1’s large-scale RL algorithm teaches the model how to think productively using its chain of thought. This RL-based training process is highly data-efficient, allowing the model to improve with more RL (train-time compute) and more time spent thinking (test-time compute). As the model spends more time on reasoning during inference, its performance consistently improves, highlighting the importance of test-time compute scaling.

- The constraints on scaling this RL-based approach differ substantially from those of traditional LLM pretraining. Rather than relying on vast datasets and expensive training regimes, o1 models can achieve significant improvements by focusing on how to think during inference, as shown in the plot from Learning to Reason with LLMs:

- This process mirrors how AlphaGo used additional compute to extend its performance envelope beyond human-level abilities by integrating real-time search during gameplay. In a similar vein, o1’s test-time compute scaling may signal the beginning of a new era in LLM capabilities.

Test Results

- OpenAI tested the o1 models against a series of benchmarks, including human exams and machine learning tasks, where they outperformed GPT-4o in most reasoning-heavy areas. Here are a few highlights:

Advanced Math Competitions

- On the AIME (American Invitational Mathematics Examination):

- GPT-4o solved ~12% of the problems.

o1-previewsolved 74% of the problems on the first try, reaching up to 93% when using more advanced techniques like consensus re-ranking.

Coding Competitions

- In Codeforces competitions,

o1-miniachieved a performance level in the 86th percentile, showcasing advanced abilities in solving and debugging code. This far exceeded the previous generation’s GPT-4o performance.

STEM Expertise

- In evaluations like the GPQA benchmark, which tests advanced knowledge in chemistry, physics, and biology, o1 models outperformed human experts, marking a significant milestone in AI-driven scientific problem-solving.

Limitations

- While the o1 models excel in reasoning and technical tasks, there are some limitations:

- Limited non-STEM knowledge:

o1-mini, optimized for STEM reasoning, underperforms in non-STEM factual tasks compared to larger models. It lacks the broad world knowledge required for answering questions on biographies, trivia, or literature, which limits its utility in those domains. - Response speed and cost: The longer reasoning times and additional token generation required for deep problem-solving can make

o1-previewslower and more costly compared to simpler models like GPT-4o. - Hidden reasoning tokens: The model generates internal reasoning tokens during inference, which are billed but not visible to the user. This can lead to higher costs, especially in use cases where extensive internal reasoning is not necessary.

- No tool or image support: The models do not support external tool usage or image inputs, limiting their versatility in multimodal tasks that require these capabilities.

- Limited non-STEM knowledge:

Use-Cases of OpenAI o1

- The o1 models shine in fields requiring high-level reasoning and structured thinking. Below are key use cases:

- Coding:

o1-previewando1-miniexcel in code generation, debugging, and solving algorithmic problems. In Codeforces competitions, o1 models performed better than 90% of human participants. - Scientific Problem-solving: These models have shown superior performance on challenging scientific benchmarks such as GPQA, solving complex problems in physics, chemistry, and biology. They outperform human PhD experts on some evaluations, demonstrating advanced problem-solving abilities.

- Math: o1 models have achieved outstanding results in mathematics competitions like AIME, solving 93% of problems when given multiple attempts and consensus voting, surpassing even top human performers.

- Coding:

Pricing and Accessibility

- Pricing for the o1 models is comparable to GPT-4 levels at launch, with

o1-previewcosting $15 per 1 million tokens (input/output) and $60 for completion tokens, whileo1-miniis offered at $3 and $12 respectively, making it a more cost-efficient option for high-throughput applications. - API Access to

o1-previewando1-miniis restricted to high-tier accounts with at least $1,000 spent, reflecting their advanced capabilities and premium pricing. These models are not yet available for broad public use.

Safety and Advancements

- The o1 models introduce a significant leap in safety and alignment through the use of chain-of-thought reasoning, allowing the models to not only solve complex problems but also to think through safety rules and apply them in real-time. This built-in safety mechanism is designed to improve the robustness of the models, making them less prone to harmful outputs or jailbreaking attempts.

Preparedness Framework

- OpenAI follows a comprehensive Preparedness Framework for ensuring the safety and reliability of the o1 models. This framework includes a series of internal and external safety tests, red-teaming exercises, and real-world evaluations across challenging scenarios to assess how well the models adhere to ethical standards and avoid harmful behavior.

- Chain-of-thought reasoning plays a critical role in safety by helping the models reason through the implications of their responses, particularly when faced with sensitive or potentially dangerous prompts. By embedding safety rules directly into their reasoning processes, o1 models can make more informed and cautious decisions.

- In evaluations,

o1-previewshowed significant improvements over GPT-4o, with a substantial increase in safe completions, particularly on jailbreaks and edge cases, such as avoiding violent content, illegal activities, and harmful advice.

External Red-teaming

- Both

o1-previewando1-miniunderwent rigorous external red-teaming evaluations to test their responses to adversarial inputs. These tests, conducted by third-party experts in cybersecurity, content policy, and international security, confirmed the models’ robustness in resisting manipulation and providing responsible outputs.

Safety Performance Metrics

- On difficult safety benchmarks like StrongREJECT,

o1-previewscored 84 out of 100, compared to GPT-4o’s 22, reflecting a major improvement in the model’s ability to adhere to ethical guidelines. - In other safety categories, such as avoiding illegal sexual content, violent harassment, and self-harm encouragement,

o1-previewshowed a marked increase in safe completions, surpassing earlier models and ensuring better alignment with human values.

Key Safety Enhancements

- Reduced Jailbreak Vulnerability: The o1 models performed exceptionally well in preventing jailbreak attempts, where malicious users attempt to manipulate the model into producing harmful or unethical content.

- Improved Compliance: The models demonstrated enhanced compliance with safety guidelines, even in challenging or ambiguous situations, outperforming earlier versions like GPT-4o across a wide range of harmful prompts.

-

Edge Case Handling: The models were also tested on benign edge cases, where the goal was to avoid unnecessary refusals while still adhering to safety standards.

o1-previewando1-miniboth showed a high level of compliance, maintaining a balance between safety and responsiveness. - By integrating chain-of-thought reasoning directly into the models’ architecture, OpenAI has made significant strides in ensuring that the o1 models not only solve complex tasks but do so in a way that aligns with ethical standards and safety regulations.

Deployment Patterns for o1 using Dynamic Task Routing

- To maximize the efficiency and performance of OpenAI’s o1 models, two complementary approaches can be integrated: a dual-net architecture and an intelligent routing system. These methods aim to dynamically allocate computational resources based on task complexity, ensuring that both cost and performance are optimized.

- Below are two key strategies to achieve this goal.

Adding a Side Network to OpenAI’s o1 Models: A Dual-Net Approach

- Based on the concept proposed in Add a SideNet to your MainNet, a potential enhancement to OpenAI’s o1 series involves integrating a smaller, faster “side network” alongside the primary “main network” to optimize performance across various tasks. The side net acts as a preliminary filter, handling simpler tasks while routing complex problems to the more powerful o1 model. This dynamic delegation improves efficiency, reduces costs, and speeds up response times by reserving o1’s deep reasoning capabilities for tasks that genuinely require it. This concept mirrors strategies from earlier AI systems, where a smaller network is paired with a larger one, creating an efficient and scalable architecture.

- Below, we detail how this approach could work with o1.

Side Net for Task Routing and Efficiency

The primary challenge in AI performance optimization lies in dynamically determining the computational resources necessary for each task. A side network—a smaller, less resource-intensive model—could serve as a preliminary filter, assessing the complexity of the task before deciding whether to route it to the more powerful main o1 network.

The side net would operate as follows:

-

Confidence Estimation: For any given input, the side net would first estimate the difficulty and provide a confidence score based on its ability to solve the task. If the side net is confident in solving the task (e.g., a simpler coding or reasoning query), it handles the problem, saving both time and cost.

-

Routing Complex Tasks: If the side net exhibits low confidence or identifies the task as too complex (e.g., tasks requiring deep mathematical reasoning or intricate multi-step logic), it passes the task to the o1 model for more in-depth reasoning.

Practical Implementation in o1

- For o1, the addition of a side net would be beneficial in several ways:

- Efficiency Gains:

- Faster Task Resolution: Tasks that are less complex can be quickly handled by the side net, allowing for faster response times and reducing the need to invoke the more resource-heavy o1 model.

- Cost-Effectiveness: By delegating simpler tasks to the side net, users could minimize the computational costs associated with the o1 model’s deep reasoning cycles, as lower-tier models generally cost less to operate.

- Dynamic Resource Allocation:

- In practice, this would mean reserving the high-level reasoning capabilities of o1 for problems that genuinely require it, thereby reducing the need for extended computation times on tasks where simpler models could suffice. This aligns with the philosophy of test-time compute scaling, where resources are allocated dynamically based on the task’s complexity.

- Estimation-Based Computation:

- Estimating the difficulty of tasks is often easier than solving them outright. This allows the side net to perform a lightweight analysis and decide whether it’s worth utilizing the more advanced reasoning processes of o1 or solving it directly. Such a strategy can prevent the o1 network from being overused on simple queries, thereby maximizing overall throughput.

Routing and Use-Case Scenarios

- The side net approach could improve the performance of o1 in several use cases:

-

Routine Coding Tasks: In scenarios like basic debugging or syntax correction, the side net could handle the tasks independently without involving the

o1-previewmodel, significantly reducing response times and token consumption. -

Complex STEM Reasoning: On more complex STEM tasks (e.g., physics problem-solving or advanced algorithmic challenges), the side net might quickly recognize its limitations and forward the problem to the o1 network, ensuring a thorough and accurate solution.

-

Conclusion

- Integrating a side net into OpenAI’s o1 architecture offers a promising pathway for enhancing performance and cost-effectiveness. By dynamically assessing the complexity of tasks and delegating them appropriately, this dual-net approach could optimize resource use, reduce computation times, and offer users a more efficient solution tailored to the difficulty of the task at hand. This fusion of side and main nets, where confidence in simpler tasks dictates the computational path, has the potential to push o1’s capabilities even further while controlling costs and maximizing response efficiency.

Adopting a Router Setup to Divert Queries

- In addition to integrating a smaller side network alongside OpenAI’s o1 models, another compelling paradigm involves leveraging RouteLLM, a routing framework proposed for dynamic model routing between a large model (such as o1) and a smaller, cost-efficient model. This will lead to a system that intelligently decides which model—a large, accurate model (

o1-preview) or a smaller, cost-efficient one (o1-minior side net)—should handle a given task. By using preference data and performance thresholds, this setup balances the cost and quality trade-off, reducing reliance on larger models without sacrificing significant response quality. This approach builds on the foundational idea of routing queries based on task complexity, allowing for cost-effective and high-performance inference.

RouteLLM: Intelligent Query Routing Between Big and Small Models

- RouteLLM introduces an efficient way to determine the appropriate model for a task dynamically, based on the complexity and expected performance requirements. This strategy is useful when deciding between a smaller model (such as

o1-minior even a simpler side net) and a larger model likeo1-preview. The router system evaluates the complexity of a given query and decides which model to invoke, thereby balancing cost and performance. The main idea is to use lightweight “routers” trained on preference data and additional techniques, such as data augmentation, to optimize the decision-making process.

Key aspects of RouteLLM routing:

- Performance vs. Cost Trade-off: The larger model (

o1-preview) is typically more accurate but costly to run, while the smaller model (o1-minior side net) is less accurate but cheaper. The router determines which model to invoke based on the task complexity. - Cost Savings: According to RouteLLM’s results, routing can save up to 2x in cost without sacrificing significant response quality. The router essentially ensures that only complex queries are passed to the more powerful model.

- Human Preference Data: RouteLLM uses human preference data to learn which types of queries require the larger model and which can be handled by the smaller one. This learning allows the router to generalize across a wide variety of tasks, making it effective for real-world applications.

Implementation with o1 Models

- For OpenAI’s o1 architecture, RouteLLM could provide the following advantages:

- Dynamic Query Evaluation:

- For tasks requiring deeper reasoning, the RouteLLM system would send the query to

o1-preview, where more extensive test-time compute can be allocated. - For simpler tasks, it could route queries to a smaller model (e.g.,

o1-mini) or a dedicated side net to reduce computational load and costs.

- For tasks requiring deeper reasoning, the RouteLLM system would send the query to

- Training the Router:

- The router can be trained using preference data similar to the RouteLLM framework, which captures the complexity of queries and the performance differences between

o1-previewando1-mini. - Data Augmentation: To improve the router’s generalization across different domains, synthetic data (e.g., from MMLU benchmarks) or automatically generated preference labels could be used to train the routing system further.

- The router can be trained using preference data similar to the RouteLLM framework, which captures the complexity of queries and the performance differences between

- Cost and Performance Optimization:

- RouteLLM demonstrated the effectiveness of this system by achieving 50% less reliance on larger models while maintaining quality through intelligent routing. This method would allow developers using o1 models to optimize for budget constraints while ensuring top-tier performance for complex tasks.

- Metrics like Cost-Performance Threshold (CPT) can help determine the best balance, with thresholds adjusted based on user preferences or task criticality.

Integration with OpenAI’s o1 Test-Time Compute

-

Extended Decision-Making: By integrating RouteLLM’s router system, the decision of how long to compute or which model to use becomes more dynamic and data-driven. The router helps decide if a task truly requires the deep reasoning capabilities of

o1-previewor if the fastero1-miniwould suffice. -

Use Case Adaptability: In environments where budget and speed are priorities, RouteLLM’s architecture ensures that only necessary computational resources are allocated for complex queries, while simpler queries are handled more efficiently. For instance, in a coding task, basic syntax fixes can be routed to

o1-mini, while complex algorithm debugging is processed byo1-preview.

Conclusion

- Incorporating a dual-model routing system like RouteLLM into OpenAI’s o1 framework enhances the decision-making process around model usage. It allows for intelligent, cost-effective routing, balancing the performance of the smaller

o1-miniwith the deeper reasoning capabilities ofo1-preview. This ensures that resources are used efficiently, optimizing both cost and task performance dynamically based on query complexity【6†source】.

Conclusion

- OpenAI’s

o1-previewando1-minimodels represent a major advancement in reasoning, safety, and coding capabilities. With chain-of-thought reasoning and RL, they can tackle complex problems with greater accuracy than previous models, making them invaluable tools for developers, scientists, and researchers. While there are still some limitations, especially in non-STEM tasks, o1 sets a new standard for AI’s reasoning capabilities.

Related Papers

Let’s Verify Step by Step

- This paper by Lightman et al. from OpenAI presents a detailed investigation into the effectiveness of process supervision compared to outcome supervision in training language models for complex multi-step reasoning.

- The authors explore the concepts of outcome and process supervision. Outcome-supervised reward models (ORMs) focus on the final result of a model’s reasoning chain, while process-supervised reward models (PRMs) receive feedback at each step in the reasoning chain.

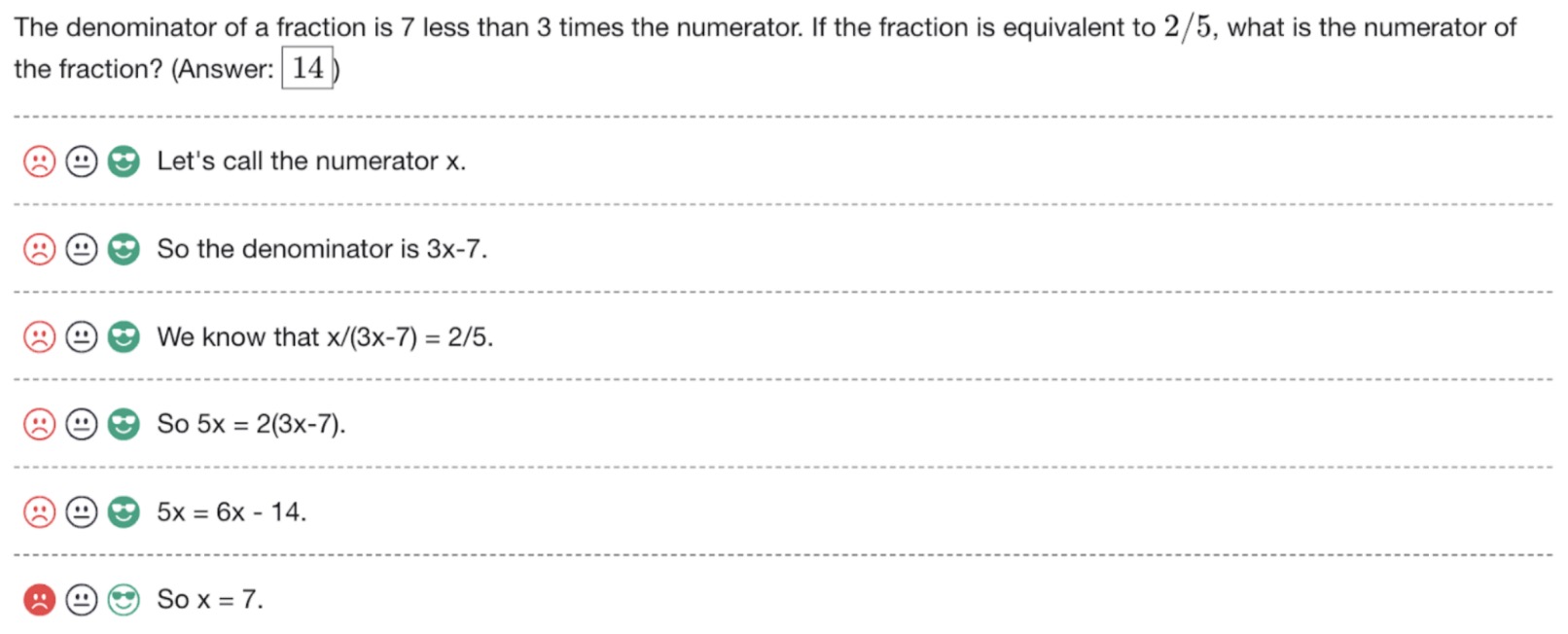

- To collect process supervision data, they present human data-labelers with step-by-step solutions to MATH problems sampled by the large-scale generator. Their task is to assign each step in the solution a label of positive, negative, or neutral, as shown in the below figure. A positive label indicates that the step is correct and reasonable. A negative label indicates that the step is either incorrect or unreasonable. A neutral label indicates ambiguity. In practice, a step may be labelled neutral if it is subtly misleading, or if it is a poor suggestion that is technically still valid. Neutral labels allows them to defer the decision about how to handle ambiguity: at test time, we can treat neutral labels as either positive or negative. The following figure from the paper shows a screenshot of the interface used to collect feedback for each step in a solution.

- The following figure from the paper shows two solutions to the same problem, graded by the PRM. The solution on the left is correct while the solution on the right is incorrect. A green background indicates a high PRM score, and a red background indicates a low score. The PRM correctly identifies the mistake in the incorrect solution.

- For their experiments, they used large-scale models fine-tuned from GPT-4 and smaller models for detailed comparisons. These models were trained on the MATH dataset, which includes complex mathematical problems.

- The paper introduces a new dataset, PRM800K, comprising 800,000 step-level human feedback labels, which was instrumental in training their PRM models.

- The key findings show that process supervision significantly outperforms outcome supervision in training models to solve complex problems. Specifically, their PRM model solved 78.2% of problems from a representative subset of the MATH test set.

- The researchers also demonstrate that active learning significantly improves the efficiency of process supervision, leading to better data utilization.

- They conducted out-of-distribution generalization tests using recent STEM tests like AP Physics and Calculus exams, where the PRM continued to outperform other methods.

- The paper discusses the implications of their findings for AI alignment, highlighting the advantages of process supervision in producing more interpretable and aligned models.

- They acknowledge potential limitations related to test set contamination but argue that the relative comparisons made in their work are robust against such issues.

- This research contributes to the field by showing the effectiveness of process supervision and active learning in improving the reasoning capabilities of language models, especially in complex domains like mathematics.

Scaling LLM Test-Time Compute Optimally can be More Effective than Scaling Model Parameters

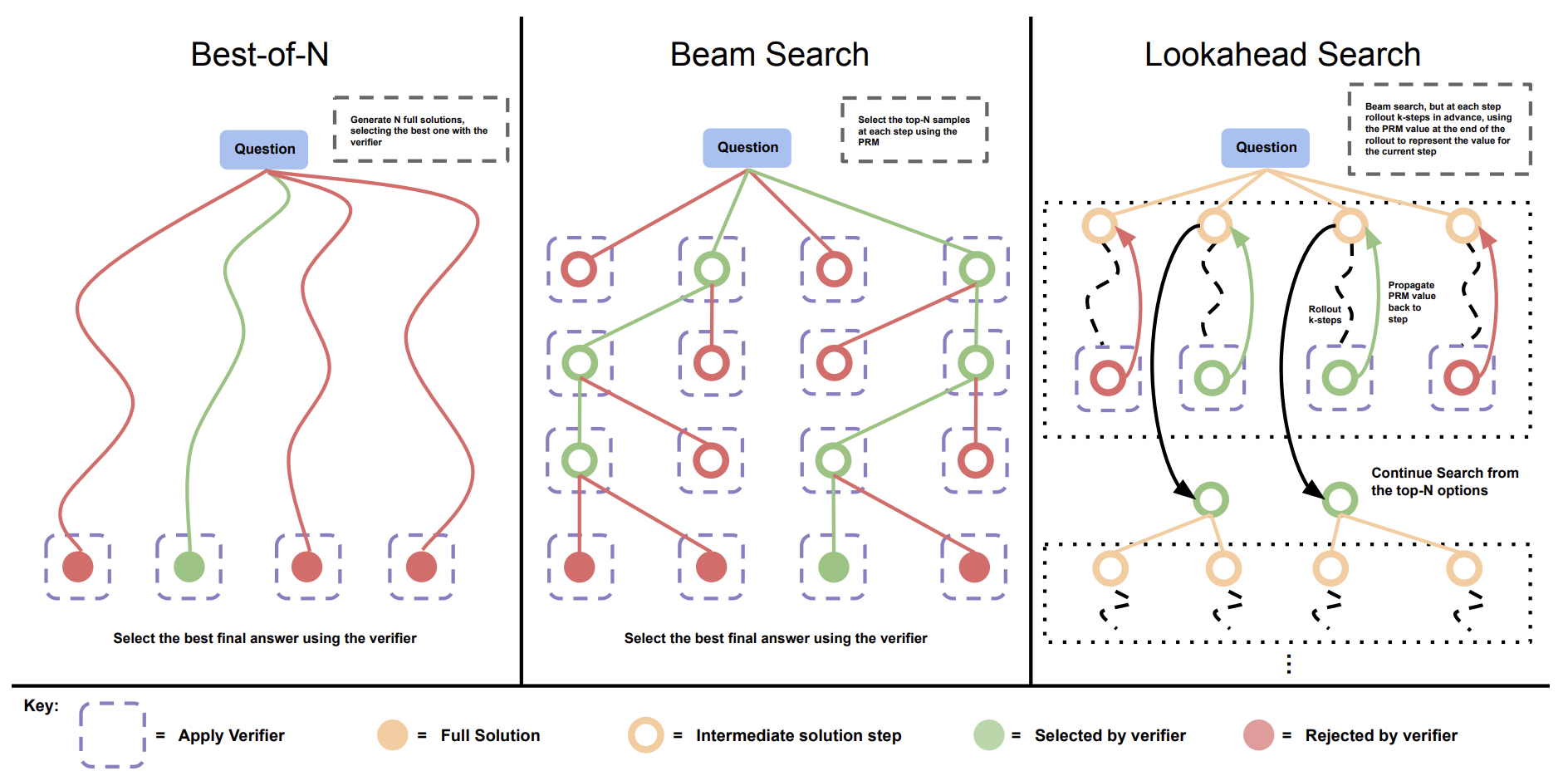

- This paper by Snell et al. from UC Berkeley and Google DeepMind explores the scaling of inference-time computation in large language models (LLMs) and addresses the question of how much a fixed amount of test-time compute can improve model performance, particularly on difficult prompts. The authors focus on two primary mechanisms to scale test-time compute: (1) searching against dense process-based verifier reward models (PRMs) and (2) adaptively updating the model’s response distribution during test time.

- The study reveals that the optimal approach for scaling test-time compute depends heavily on prompt difficulty. Based on this insight, the authors propose a “compute-optimal” scaling strategy, which adaptively allocates test-time compute depending on the problem’s complexity. This strategy improves efficiency by more than 4× compared to standard best-of-N sampling and can, under certain conditions, outperform models 14× larger with matched FLOPs.

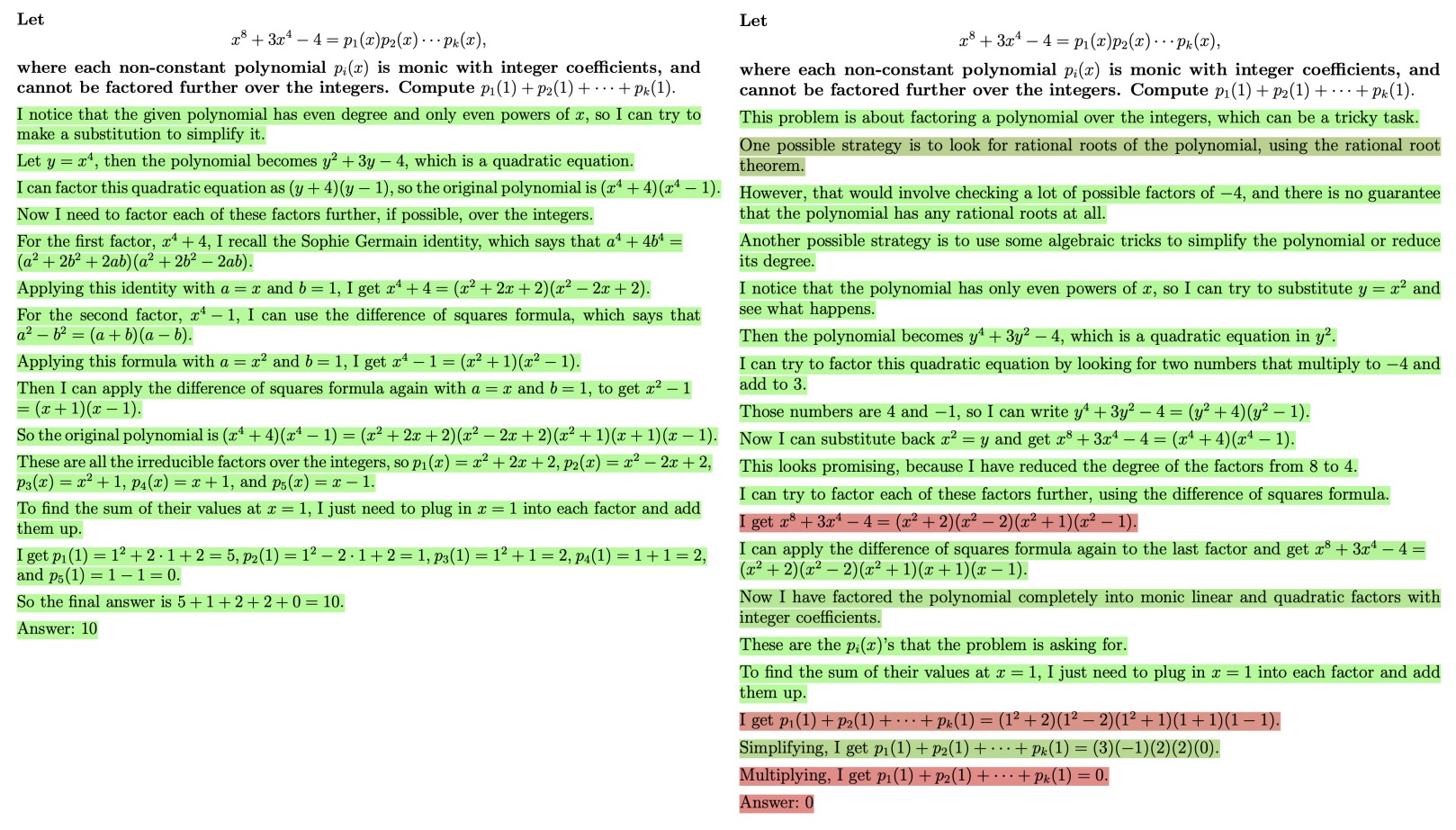

- In their experimental setup, they use PaLM 2-S (Codey) models fine-tuned for revision and verification tasks, evaluated on the challenging MATH benchmark. They evaluate methods to scale test-time compute, including revising answers iteratively and searching for correct solutions using PRMs. Key findings include:

- Revisions: When the LLM iteratively refines its responses, it achieves better performance on easier tasks by revising and optimizing its original answers. For more complex problems, parallel sampling (best-of-N) is generally more effective, especially when multiple high-level solution approaches must be explored.

- PRM-based Search: Process-based verifiers perform step-by-step evaluations of solutions, offering better guidance on complex problems. Beam search and lookahead search methods were explored, with beam search showing higher efficiency on more difficult prompts when the compute budget is limited. The following figure from the paper shows a comparison of different PRM search methods. Left: Best-of-\(N\) samples \(N\) full answers and then selects the best answer according to the PRM final score. Center: Beam search samples \(N\) candidates at each step, and selects the top \(M\) according to the PRM to continue the search from. Right: lookahead-search extends each step in beam-search to utilize a k-step lookahead while assessing which steps to retain and continue the search from. Thus lookahead-search needs more compute.

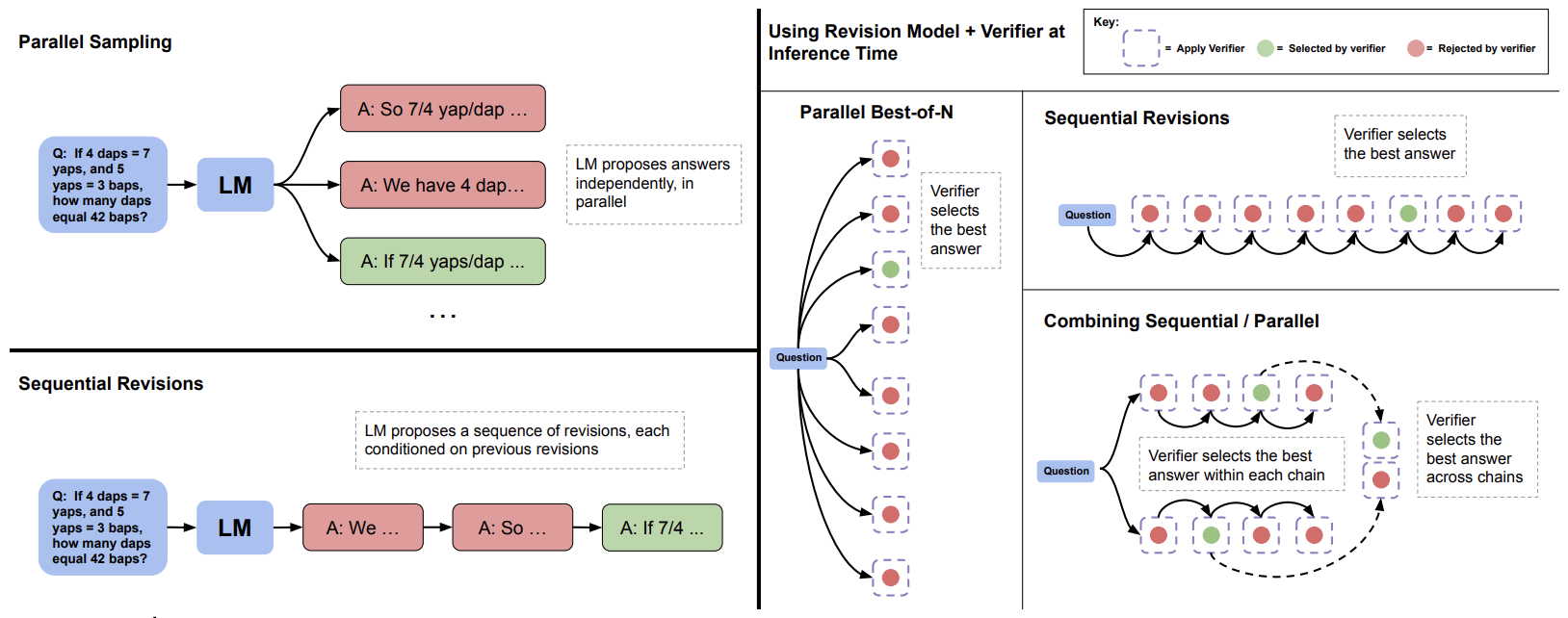

- The following figure from the paper shows parallel sampling (e.g., Best-of-\(N\)) verses sequential revisions. Left: Parallel sampling generates \(N\) answers independently in parallel, whereas sequential revisions generates each one in sequence conditioned on previous attempts. Right: In both the sequential and parallel cases, we can use the verifier to determine the best-of-\(N\) answers (e.g. by applying best-of-\(N\) weighted). We can also allocate some of our budget to parallel and some to sequential, effectively enabling a combination of the two sampling strategies. In this case, we use the verifier to first select the best answer within each sequential chain and then select the best answer accross chains.

- The paper emphasizes that adaptive test-time compute scaling, based on the difficulty of the question, is essential. The proposed compute-optimal scaling strategy outperforms best-of-\(N\) with significantly less computation, particularly for easy and intermediate tasks. By dynamically choosing between search-based and revision-based methods, the authors demonstrate a practical way to optimize LLM performance within a constrained computational budget.

- In addition, they show that test-time compute can be a viable substitute for additional pretraining, especially when handling easier questions or lower inference workloads. On the other hand, for harder questions, additional pretraining remains more effective. This tradeoff suggests that in specific deployment scenarios (e.g., where smaller models are desirable), emphasizing test-time compute scaling might reduce the need for training significantly larger models.

- Finally, the authors propose future directions, including combining different methods of test-time compute (e.g., revisions and PRM-based search) and refining difficulty assessment during inference to further optimize test-time compute allocation.

STaR: Self-Taught Reasoner: Bootstrapping Reasoning With Reasoning

- This paper by Zelikman et al. from Stanford and Google introduces the Self-Taught Reasoner (STaR), a technique for bootstrapping the ability of large language models (LLMs) to generate reasoning-based answers (rationales) iteratively. The goal of STaR is to improve the LLM’s performance on complex reasoning tasks like arithmetic and commonsense question answering without the need for manually curated large datasets of rationales. Instead, the method iteratively generates and fine-tunes rationales using a small set of initial examples, allowing the model to “teach itself” more complex reasoning over time.

- The core of the STaR approach relies on a simple yet iterative loop:

- Rationale Generation: A pretrained LLM is prompted with a few rationale examples (e.g., 10 for arithmetic) and tasked with generating rationales for a set of questions. Only rationales that yield correct answers are retained.

- Fine-Tuning: The model is fine-tuned on these filtered correct rationales to improve its ability to generate them.

- Rationalization: For problems where the model fails to generate correct answers, it is provided with the correct answer and asked to “rationalize” it by generating a rationale. This technique allows the model to improve by reasoning backward from the correct answer.

- This process is repeated across multiple iterations, with the model learning to solve increasingly complex tasks through rationale generation and rationalization.

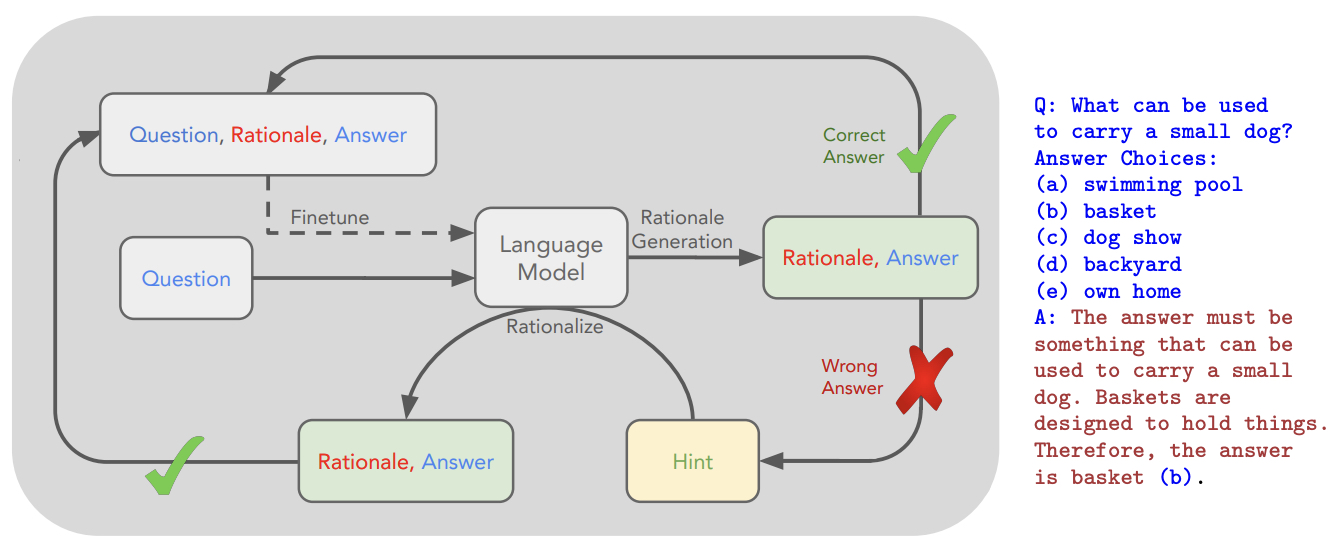

- The following figure from the paper shows an overview of STaR and a STaR-generated rationale on CommonsenseQA. We indicate the fine-tuning outer loop with a dashed line. The questions and ground truth answers are expected to be present in the dataset, while the rationales are generated using STaR.

- Implementation Details:

- Initial Setup: STaR starts with a small prompt set of rationale-annotated examples (e.g., 10 examples in the case of arithmetic). Each example in the dataset is then augmented with these few-shot rationales, encouraging the model to generate a rationale for the given question.

- Filtering: Rationales are filtered by whether they result in the correct final answer, and only correct rationales are used for fine-tuning.

- Training Process: The model is fine-tuned in a loop, with the number of fine-tuning steps increased by 20% per iteration. Fine-tuning starts with 40 training steps and slowly scales up.

- Rationalization: When the model fails to generate a correct rationale, it is prompted with the correct answer and asked to generate a rationale based on this information. These rationales are added to the fine-tuning dataset for further improvement.

- Avoiding Overfitting: The model is always retrained from the original pre-trained model rather than continuing to train the same model across iterations, to prevent overfitting.

- Results:

- Arithmetic: The model’s performance improved significantly after each iteration. Without rationalization, STaR improved performance on n-digit addition problems in a stage-wise fashion (improving on simpler problems first), while rationalization enabled the model to learn across different problem sizes simultaneously.

- CommonsenseQA: STaR outperformed a GPT-J model fine-tuned directly on answers, achieving 72.5% accuracy compared to 73.0% for a 30× larger GPT-3 model. STaR with rationalization outperformed models without rationalization, indicating the added benefit of rationalizing incorrect answers.

- Generalization: The STaR approach also demonstrated the ability to generalize beyond training data, solving unseen, out-of-distribution problems in arithmetic.

- Key Contributions:

- STaR provides a scalable bootstrapping technique that allows models to iteratively improve their reasoning abilities without relying on large rationale-annotated datasets.

- The inclusion of rationalization as a mechanism for solving problems that the model initially fails to answer correctly enhances the training process by exposing the model to more difficult problems.

- STaR’s iterative approach makes it a broadly applicable method for improving model reasoning across domains, including arithmetic and commonsense reasoning tasks.

- In summary, STaR introduces a novel iterative reasoning-based training approach that improves the reasoning capability of LLMs using a small set of rationale examples and a large dataset without rationales. This method significantly enhances model performance on both symbolic and natural language reasoning tasks.

Quiet-STaR: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Think Before Speaking

- This paper by Zelikman from Stanford and Notbad AI, generalizes the Self-Taught Reasoner (STaR) method by teaching language models (LMs) to reason implicitly through continuous text without relying on curated reasoning datasets. The key idea behind Quiet-STaR is to allow LMs to generate “thoughts” or rationales at each token position, helping predict future tokens and improving overall performance. The authors extend the STaR approach, which previously focused on specific tasks like question-answering, to a more general framework where the LM generates and learns from rationales embedded in arbitrary text.

- The core implementation of Quiet-STaR involves three major steps:

- Parallel Rationale Generation: The LM generates rationales after every token to explain the continuation of future tokens. A key challenge resolved here is the computational inefficiency of generating continuations at every token. The authors propose a token-wise parallel sampling algorithm that allows for efficient generation by caching forward passes and employing diagonal attention masking.

- Mixing Head for Prediction Integration: A “mixing head” model is trained to combine predictions made with and without rationales. This helps manage the distribution shift caused by introducing rationales in a pre-trained model. The head outputs a weight that determines how much the rationale-based prediction should influence the overall token prediction.

- Rationale Optimization with REINFORCE: The model’s rationale generation is optimized using a REINFORCE-based objective, rewarding rationales that improve the likelihood of future token predictions. This method allows the LM to learn to generate rationales that help predict the next tokens more effectively, based on feedback from their impact on future token prediction.

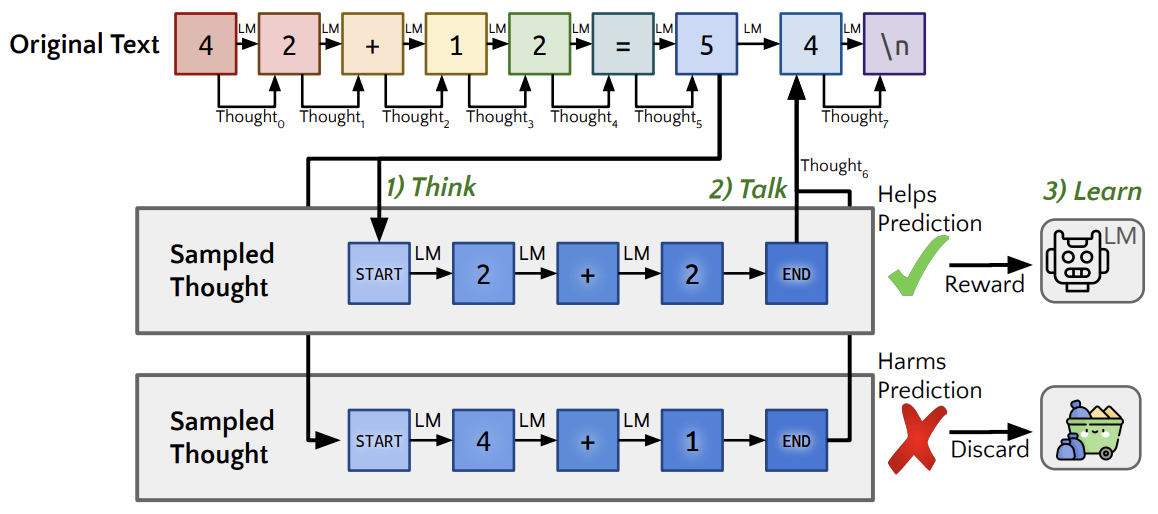

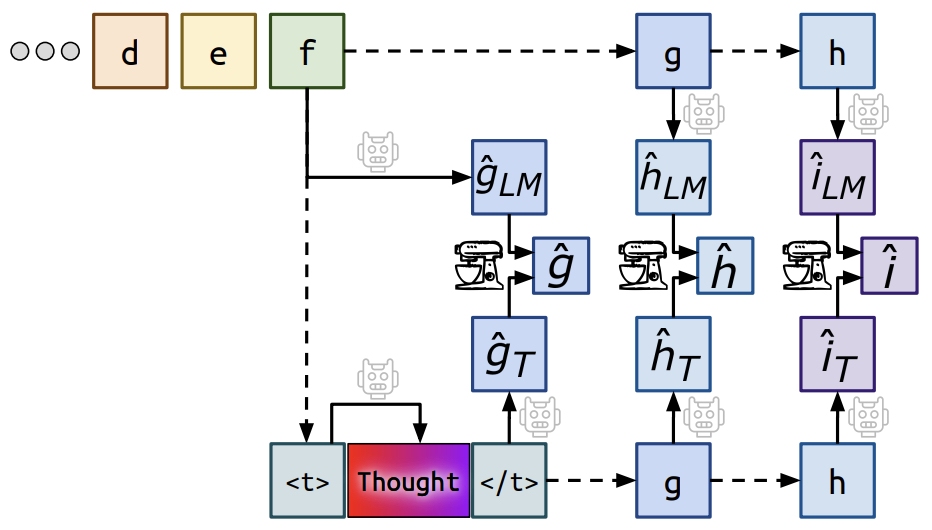

- The following figure from the paper shows Quiet-STaR visualized as applied during training to a single thought. We generate thoughts, in parallel, following all tokens in the text (think). The model produces a mixture of its next-token predictions with and without a thought (talk). They apply REINFORCE, as in STaR, to increase the likelihood of thoughts that help the model predict future text while discarding thoughts that make the future text less likely (learn).

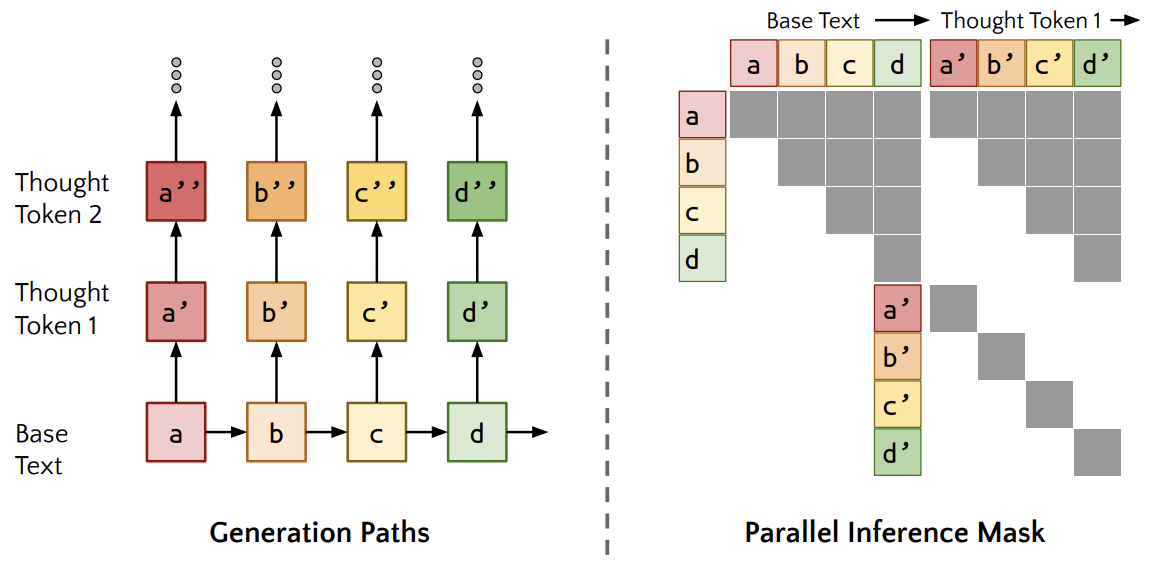

- The following figure from the paper shows parallel generation. By constructing an attention mask that allows all thought tokens to pay attention to themselves, all preceding thought tokens within the same thought, and the preceding text, we can generate continuations of all of the thoughts in parallel. Each inference call is used to generate one additional thought token for all text tokens.

- The following figure from the paper shows the forward pass and teacher forcing. We visualize a single forward pass of our algorithm. Solid lines denote language model computation, while dashed lines indicate tokens are inserted via teacher forcing, and the mixer represents the mixing head. In particular, we visualize predicting three tokens ahead. Thought generation is shown in more detail in the above two figures.

- The authors also introduce custom tokens, specifically

<|startofthought|>and<|endofthought|>, which mark the beginning and end of the rationale generation. These tokens are initialized based on the LM’s existing knowledge (e.g., em dash “−−−”) and fine-tuned for optimal performance. - One of the significant findings from the experiments was that training with Quiet-STaR on diverse text datasets (like C4 and OpenWebMath) improved zero-shot reasoning abilities on commonsense reasoning tasks like GSM8K and CommonsenseQA. The LM showed improved performance in reasoning tasks without any task-specific fine-tuning, demonstrating the effectiveness of Quiet-STaR in enhancing reasoning in LMs in a generalizable and scalable way.

- For example, zero-shot performance on GSM8K improved from 5.9% to 10.9%, and on CommonsenseQA from 36.3% to 47.2%. These improvements are primarily driven by difficult-to-predict tokens, where Quiet-STaR’s rationales prove most beneficial. Furthermore, longer thought sequences resulted in better predictions, suggesting that more detailed reasoning steps enhance token prediction accuracy.

- The computational overhead of Quiet-STaR is notable, as generating rationales adds complexity. However, the authors argue that this overhead can be leveraged to improve the model’s performance in tasks that require deeper reasoning. The results suggest that Quiet-STaR can enhance not only language modeling but also chain-of-thought reasoning, where reasoning steps are crucial for solving more complex tasks.

- In conclusion, Quiet-STaR represents a significant step towards generalizable reasoning in language models by embedding continuous rationales in text generation, ultimately leading to better zero-shot reasoning performance across a range of tasks. The method also opens up potential future directions, such as dynamically predicting when rationale generation is needed and ensembling rationales for further improvements in reasoning capabilities.

Large Language Monkeys: Scaling Inference Compute with Repeated Sampling

- This paper by Brown et al. from Stanford, University of Oxford, and Google DeepMind, explores a novel methodology for scaling inference compute in large language models (LLMs) by utilizing repeated sampling. Instead of relying on a single inference attempt per problem, the authors propose increasing the number of generated samples to improve task coverage, particularly in tasks where answers can be automatically verified.

- The paper investigates two key aspects of the repeated sampling strategy:

- Coverage: The fraction of problems that can be solved by any generated sample.

- Precision: The ability to identify the correct solution from the generated samples.

- Technical Details: The authors demonstrate that by scaling the number of inference samples, task coverage can increase exponentially across various domains such as coding and formal proofs, where answers are verifiable. For instance, using the SWE-bench Lite benchmark, the fraction of issues solved with DeepSeek-V2-Coder-Instruct increased from 15.9% with one sample to 56% with 250 samples, surpassing the state-of-the-art performance of 43% by more capable models like GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet.

- Key Observations:

- Log-linear scaling of coverage: Across multiple models (e.g., Llama-3 and Gemma), the coverage exhibits a nearly log-linear relationship with the number of generated samples. This scaling behavior is modeled with an exponentiated power law, indicating the existence of potential inference-time scaling laws.

- Cost-efficiency: Repeated sampling of cheaper models like DeepSeek can outperform single-sample inferences from premium models (e.g., GPT-4o) in terms of both performance and cost-effectiveness, providing up to 3x cost savings.

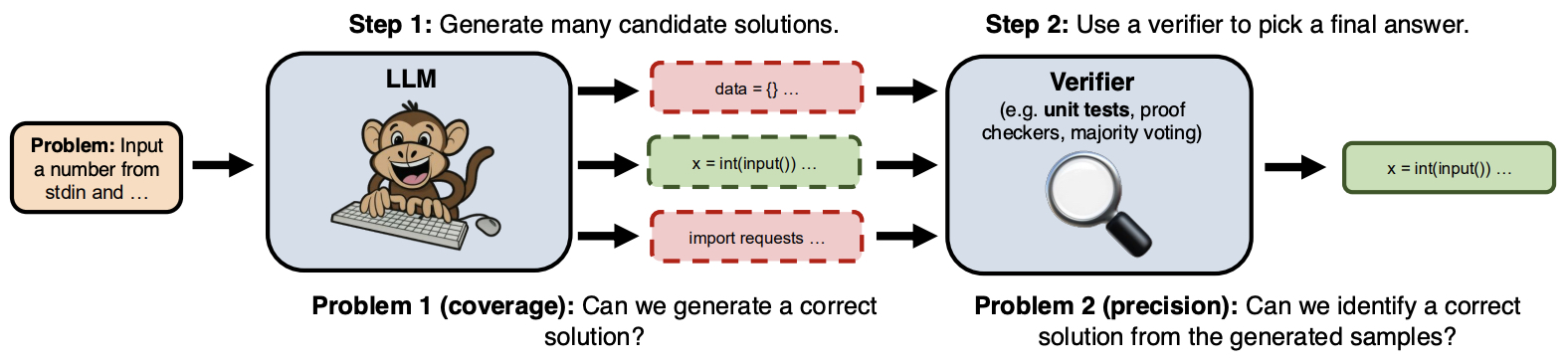

- The following figure from the paper shows the proposed repeated sampling procedure: (i) Generate many candidate solutions for a given problem by sampling from an LLM with a positive temperature. (ii) Use a domain-specific verifier (ex. unit tests for code) to select a final answer from the generated samples.

- Implementation:

The repeated sampling methodology is implemented through the following steps:

- Sample generation: For each problem, multiple candidate solutions are generated by the LLM with a positive sampling temperature.

- Verification: Solutions are verified using domain-specific verifiers (e.g., unit tests for code or proof checkers for formal proofs). In domains like coding, verification is fully automatic, translating the increased coverage into better performance.

- Evaluation of Coverage: Coverage is evaluated using metrics such as pass@k, where k is the number of generated samples. For example, pass@10,000 was used to evaluate the CodeContests and MATH datasets.

- Empirical Results:

- Programming tasks: On the CodeContests dataset, the coverage of weaker models like Gemma-2B increased from 0.02% with one sample to 7.1% with 10,000 samples.

- Mathematical problems: For math word problems from the GSM8K and MATH datasets, coverage increased to over 95% with 10,000 samples. However, methods to select the correct solution, such as majority voting or reward models, plateau after several hundred samples, highlighting the need for better solution selection mechanisms.

- Future Directions: The paper points out that identifying correct solutions from multiple samples remains a challenge in domains without automatic verifiers (e.g., math word problems). Additionally, the work opens up further research avenues, including optimizing sample diversity and leveraging multi-turn interactions for iterative problem-solving.

- This work underscores the potential of scaling inference compute through repeated sampling, demonstrating significant improvements in model performance while offering a cost-effective alternative to using larger, more expensive models.

Learn Beyond The Answer: Training Language Models with Reflection for Mathematical Reasoning

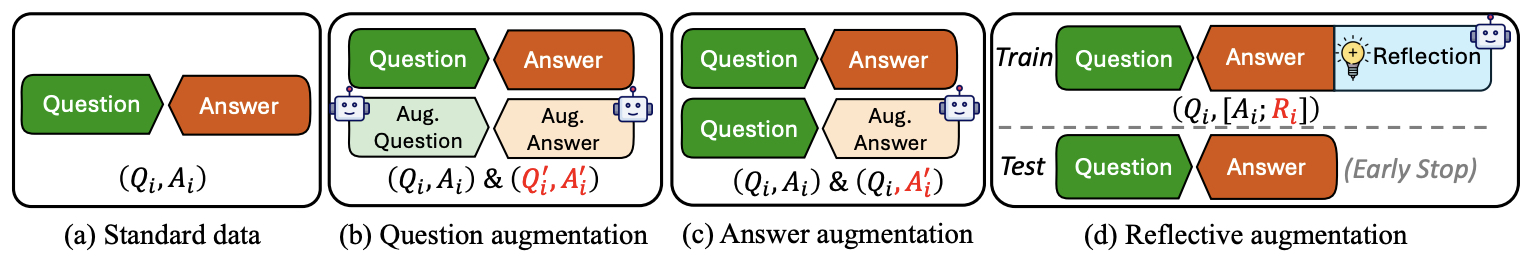

- This paper by Zhang et al. from the University of Notre Dame and Tencent AI Lab introduces Reflective Augmentation (RefAug), a novel method designed to improve the performance of language models (LMs) in mathematical reasoning tasks, particularly those requiring deeper comprehension through reflection. Traditional data augmentation approaches have focused on increasing the quantity of training instances, which improves problem-solving skills in simple, single-round question-answering (QA) tasks. However, these methods are less effective for complex reasoning scenarios where a more reflective approach is needed. RefAug addresses this limitation by adding reflective components to the training sequences, encouraging LMs to engage in alternative reasoning and follow-up reasoning.

- Key Contributions:

- Reflective Augmentation:

- RefAug enhances each training instance by appending a reflective section after the standard solution. This section helps the LM reflect on the problem, promoting deeper understanding and enabling it to consider alternative methods and apply abstractions or analogies.

- Two types of reflection are included:

- Alternative reasoning: Encourages the model to consider different methods for solving the problem.

- Follow-up reasoning: Either focuses on abstraction (generalizing the problem) or analogy (applying the same technique to more complex problems).

- Implementation:

- The paper uses GPT-4-turbo as an expert model to annotate reflective sections for training, minimizing human involvement and ensuring high-quality reasoning.

- The training objective is extended to optimize for the concatenation of the original answer and the reflective section. During training, the model learns the full reasoning sequence but during inference, the reflective part is excluded to maintain efficiency.

- Experiments were conducted with LMs such as Mistral-7B and Gemma-7B, testing them on mathematical reasoning tasks with and without reflective augmentation.

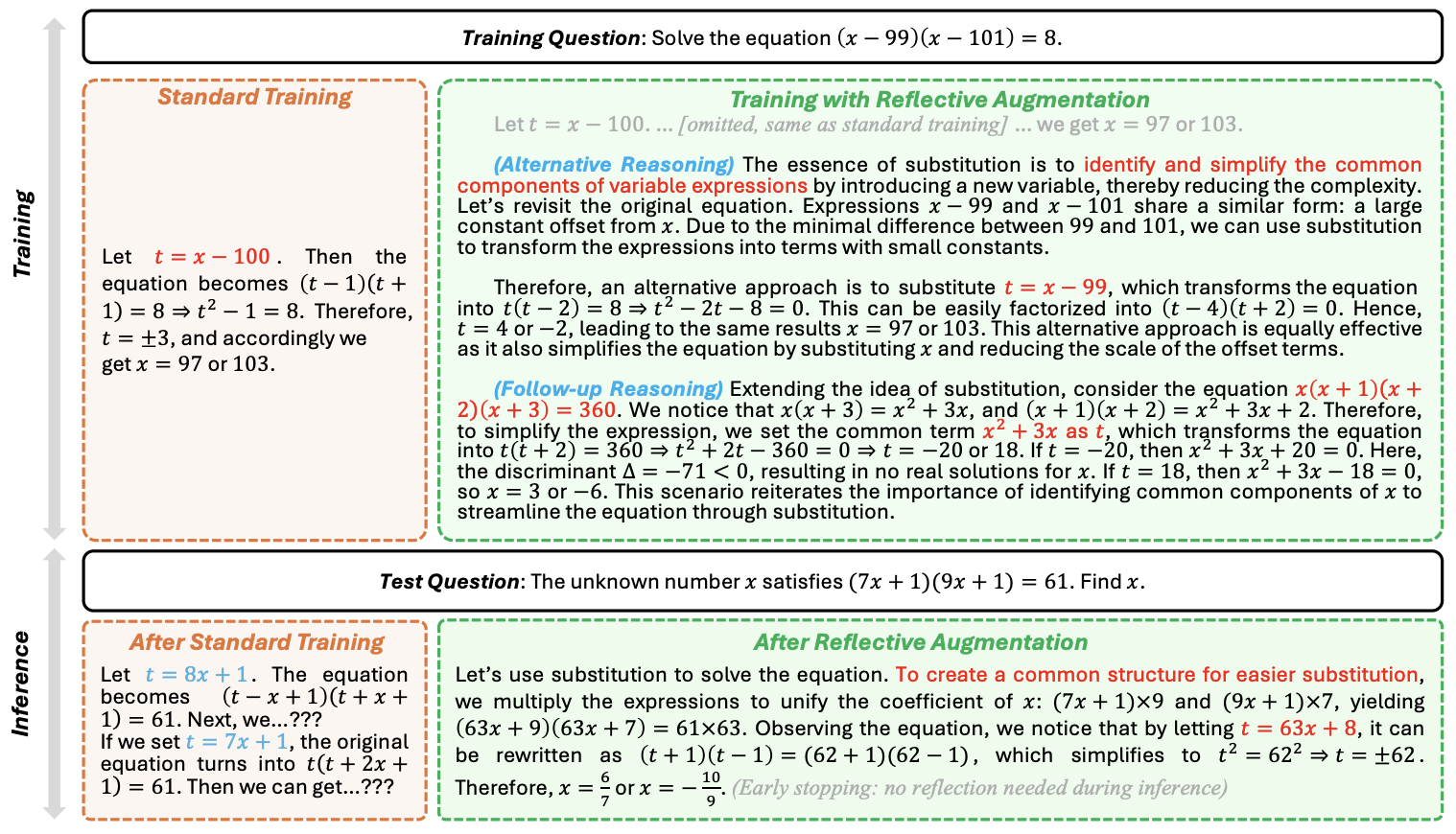

- The following figure from the paper shows that question augmentation creates new questions based on existing ones. Answer augmentation re-samples answers for each problem to increase diversity. Both methods expand the size of the training set. Reflective augmentation appends the original answer with a reflective section, which is complementary to traditional approaches. Corresponding training sequences are shown in an (input, output) format, where augmented parts are in red.

- The following figure from the paper shows that the model that learned the standard solution does not fully understand when and how to apply substitution when facing a different scenario. In contrast, the model trained with reflection on the substitution technique gains a deeper understanding of its principles, patterns, and its flexible application in new contexts.

- Performance:

- Substantial improvement in standard QA: RefAug enhances performance in single-round QA by +7.2 accuracy points, demonstrating its ability to help models learn problem-solving skills more effectively.

- Superior results in reflective reasoning tasks: RefAug significantly boosts the model’s capabilities in handling follow-up questions and error correction, areas where traditional augmentation techniques falter.

- Complementary to traditional augmentation: Combining RefAug with other augmentation methods (such as question and answer augmentation) leads to further gains, showing its effectiveness as a complementary approach.

- Scalability:

- RefAug proved effective even when applied to large datasets, like MetaMath, with results improving by 2 percentage points over baseline models trained on the same data without reflective sections.

- Reflective Augmentation:

- Experimental Results:

- Models trained with RefAug outperformed their standard counterparts in both in-distribution and out-of-distribution mathematical tasks (such as GSM8k, MATH, MAWPS, etc.).

- On reflective reasoning tasks (e.g., MathChat and MINT), RefAug-augmented models demonstrated a marked improvement, particularly in multi-step and follow-up questions.

- Significance:

- RefAug goes beyond conventional data expansion techniques by embedding reflective thinking into training data, which strengthens a model’s ability to generalize and reason in diverse mathematical contexts. This method shows great promise for enhancing LMs in tasks requiring flexible problem-solving and deeper conceptual understanding.

- The approach is designed to be easily integrated with other augmentation methods, improving the overall efficiency and effectiveness of language models in mathematical reasoning tasks.

Agent Q: Advanced Reasoning and Learning for Autonomous AI Agents

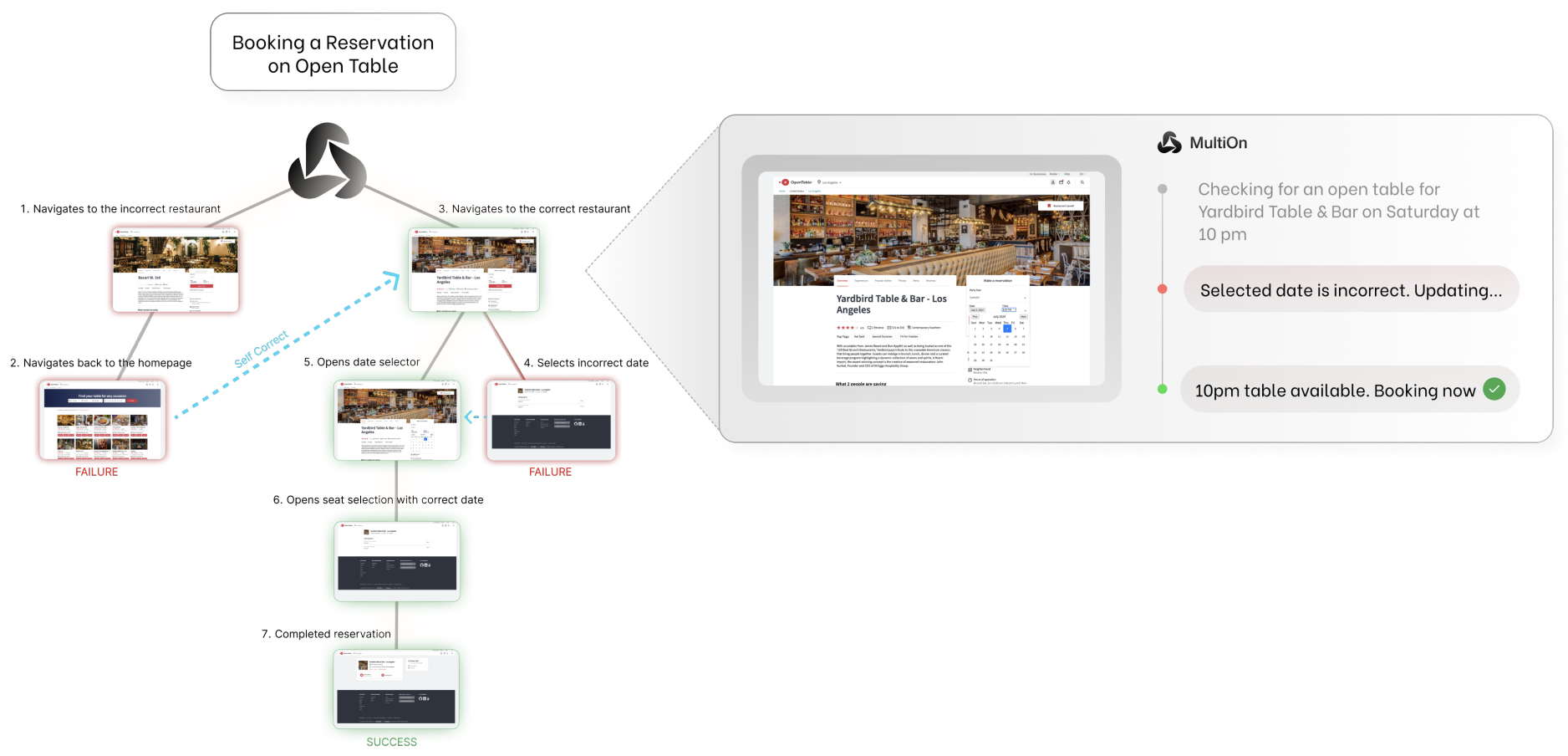

- This paper by Putta et al. from MultiOn and Stanford, presents “Agent Q,” a novel framework that enhances the reasoning and decision-making capabilities of large language models (LLMs) in agentic, multi-step tasks in dynamic environments such as web navigation. The framework tackles challenges related to compounding errors and limited exploration data that hinder LLMs from excelling in autonomous, real-time decision-making scenarios.

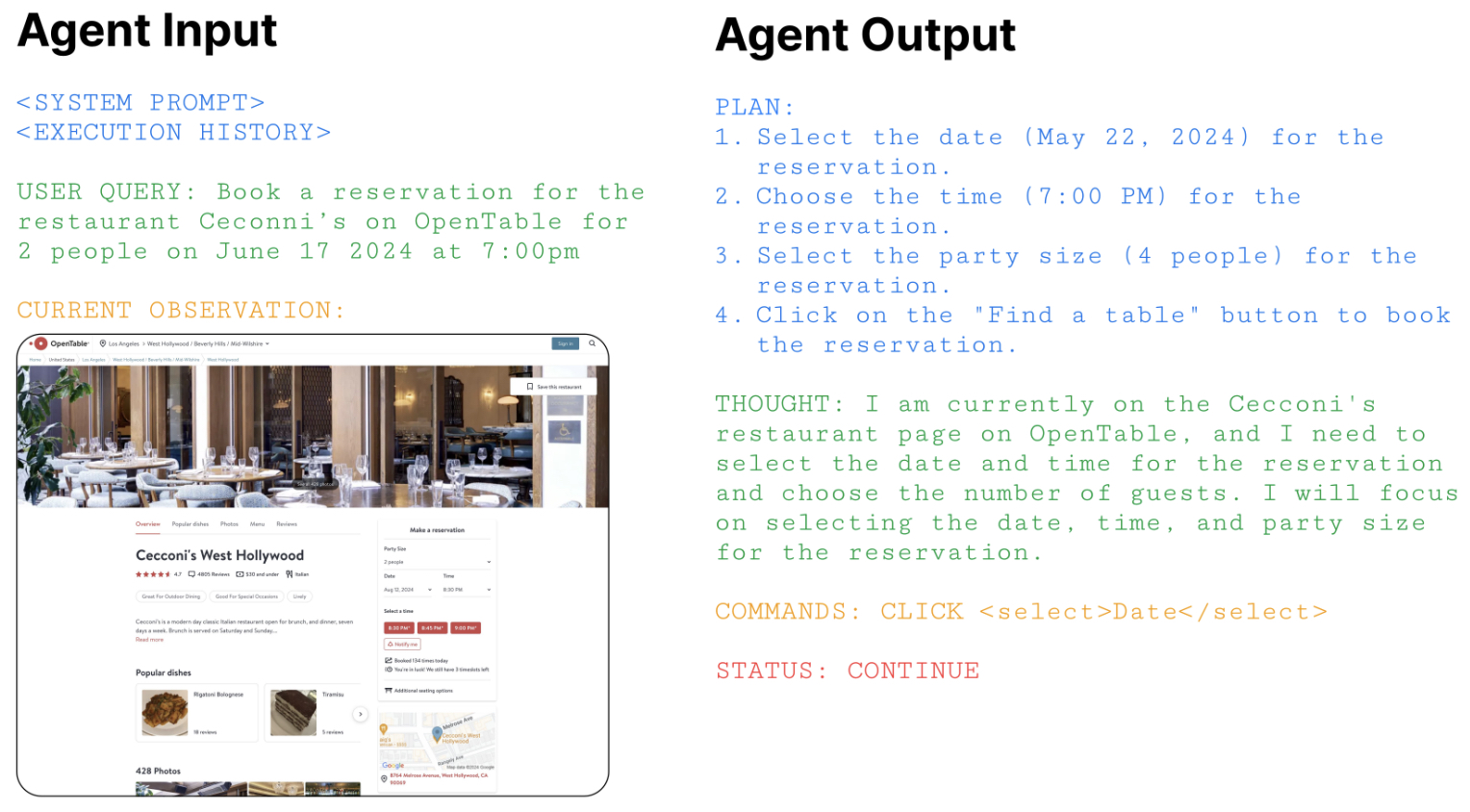

- The authors propose a method that integrates guided Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) with a self-critique mechanism. This enables the agent to iteratively improve by learning from both successful and unsuccessful trajectories, using an off-policy variant of Direct Preference Optimization (DPO). The agent operates in a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) framework, where the LLM is responsible for planning, reasoning, and interacting with the environment, such as executing commands on web pages.

-Key Components of Agent Q:

-

Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS): MCTS is used for exploring multiple action trajectories. It evaluates possible actions at each node (web page) by calculating rewards and assigning values to each action. The Upper Confidence Bound (UCB1) strategy guides the exploration versus exploitation trade-off. To handle the sparse reward environment, an AI-based feedback mechanism is employed to rank actions and provide step-level guidance.

-

Direct Preference Optimization (DPO): DPO helps optimize the agent by using preference pairs (successful vs. unsuccessful actions) collected during interaction. This approach mitigates the need for a large number of online samples, making it computationally efficient for offline training. The DPO algorithm allows the agent to refine its decision-making policy by comparing trajectory outcomes and constructing preference pairs for learning.

-

Self-Critique Mechanism: To overcome credit assignment problems (where small errors can lead to overall task failure), the model incorporates a self-critique mechanism. At each step, the LLM provides intermediate feedback, which serves as an implicit reward, helping the agent refine its future actions. -Implementation Details:

- Initial Setup: The LLaMA-3 70B model serves as the base agent. The agent is evaluated in the WebShop environment (a simulated e-commerce platform) and a real-world reservation system (OpenTable). Initial observations and user queries are represented as HTML DOM trees, and the agent’s actions are composite, consisting of planning, reasoning, environment interaction, and explanation steps.

- Training Process: The agent is trained using a combination of offline and online learning methods. Offline learning leverages the DPO algorithm to learn from past trajectories, while online learning uses MCTS to guide real-time action selection. The model continuously improves through iterative fine-tuning based on the outcomes of the agent’s decisions.

-

- The following figure from the paper shows the use of Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to guide trajectory collection and iteratively improve model performance using direct preference optimization (DPO). We begin on the left by sampling a user query from the list of tasks in the dataset. We iteratively expand the search tree using UCB1 as a heuristic to balance exploration and exploitation of different actions. We store the accumulated reward obtained for each node in the tree, where in this image darker green indicates higher reward and darker red indicates lower reward. To construct the preference dataset, we compute a weighted score of the MCTS average Q-value and score generated by a feedback language model to construct contrastive pairs for DPO. The policy is optimized and can be iteratively improved.

- The following figure from the paper shows that they provide the following input format to the Agent, consisting of the system prompt, execution history, the current observation as a DOM representation, and the user query containing the goal. We divide our Agent output format into an overall step-by-step plan, thought, a command, and a status code.

-Results: - In WebShop, Agent Q outperforms baseline models such as behavior cloning and reinforced fine-tuning, achieving a success rate of 50.5%, surpassing the average human performance of 50%. - In real-world experiments on OpenTable, the Agent Q framework improves the LLaMA-3 model’s zero-shot performance from 18.6% to 81.7%, with a further increase to 95.4% when MCTS is utilized during inference.

- This framework demonstrates significant progress in building autonomous web agents that can generalize and learn from their experiences in complex, multi-step reasoning tasks.

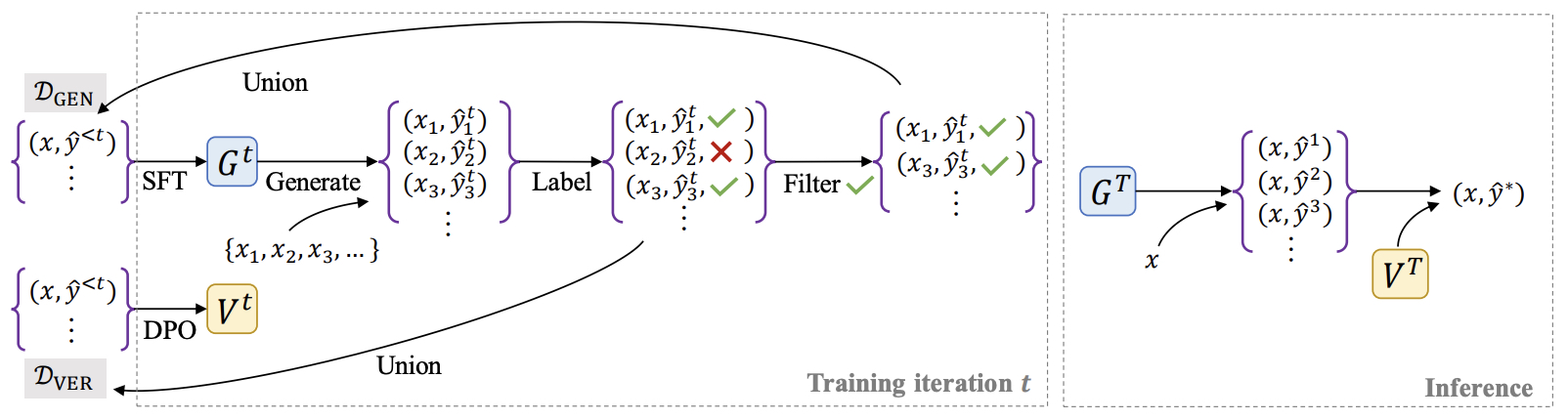

V-STaR: Training Verifiers for Self-Taught Reasoners

- This paper by Hosseini et al. from Mila, MSR, University of Edinburgh, and Google Deepmind, published in COLM 2024, introduces V-STaR, a novel approach designed to improve the reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs) by training both a verifier and a generator using correct and incorrect solutions. The authors aim to address a key limitation in previous self-improvement approaches, such as STaR and Rejection Fine-Tuning (RFT), which discard incorrect solutions, potentially missing valuable learning opportunities. V-STaR instead leverages both correct and incorrect model-generated solutions in an iterative self-improvement process, leading to better performance in tasks like math problem-solving and code generation.

- The core idea of V-STaR is to iteratively train a generator to produce solutions and a verifier to judge their correctness using Direct Preference Optimization (DPO). By utilizing both correct and incorrect solutions, V-STaR ensures that the verifier learns from the generator’s errors, making it more robust.

- Methodology and Implementation Details:

- Training the Generator (GSFT): The generator is initially fine-tuned using supervised fine-tuning (SFT) on the original dataset, producing solutions for various problem instances. After each iteration, correct solutions are added to the training data for future iterations.

- Training the Verifier (VT): Both correct and incorrect generated solutions are added to the verifier’s training data. The verifier is trained using DPO, which optimizes for preference learning by contrasting correct and incorrect solutions, improving its ability to rank solutions based on correctness.

- Iterative Process: This process is repeated for multiple iterations. In each iteration, the generator produces solutions, and the verifier learns from both the correct and incorrect solutions, progressively improving the overall performance of both models.

- Test-time Verification: At test time, the generator produces multiple candidate solutions for a problem, and the verifier selects the best one by ranking them.

- The following figure from the paper shows generator and verifier training in V-STaR. Left: In each training iteration, the generator $G^t$ is fine-tuned (from a pretrained LLM) on the current buffer of problem instances and correct solutions $\mathcal{D}{\text {GEN }}$. Generated solutions that yielded a correct answer are added to $\mathcal{D}{\mathrm{GEN}}$ to be used in future iterations, and all the generated solutions (correct and incorrect) are added to $\mathcal{D}{\text {VER }}$. The verifier $V^t$ is trained using DPO with a preference dataset constructed from pairs of correct and incorrect solutions from $\mathcal{D}{\text {VER }}$. Right: At test time, the verifier is used to rank solutions produced by the generator. Such iterative training and inference-time ranking yields large improvements over generator-only self-improvement.

- Key Results:

- V-STaR demonstrates a 4% to 17% improvement in test accuracy over baseline self-improvement and verification methods in tasks like code generation and math reasoning. In some cases, it even surpasses much larger models.

- When evaluated on math reasoning benchmarks such as GSM8K and MATH, and code-generation datasets like MBPP and HumanEval, V-STaR outperforms prior approaches by combining both correct and incorrect examples for training the verifier.

- Empirical Findings:

- The paper compares V-STaR against several baselines, including non-iterative versions of STaR and RFT combined with a verifier, and demonstrates significant improvements in Pass@1 and Best-of-64 metrics.

- V-STaR is highly data-efficient, with the iterative collection of correct and incorrect solutions leading to more challenging examples for the verifier, which enhances both the generator and verifier over time.

- Conclusions: The V-STaR approach significantly enhances reasoning tasks by training LLMs to learn from both correct and incorrect solutions. The iterative training process allows both the generator and verifier to continuously improve, and the use of DPO for training verifiers has been shown to outperform more traditional ORM-style verification methods. This framework is simple to implement and applicable to a wide range of reasoning problems, provided there is access to correctness feedback during training.

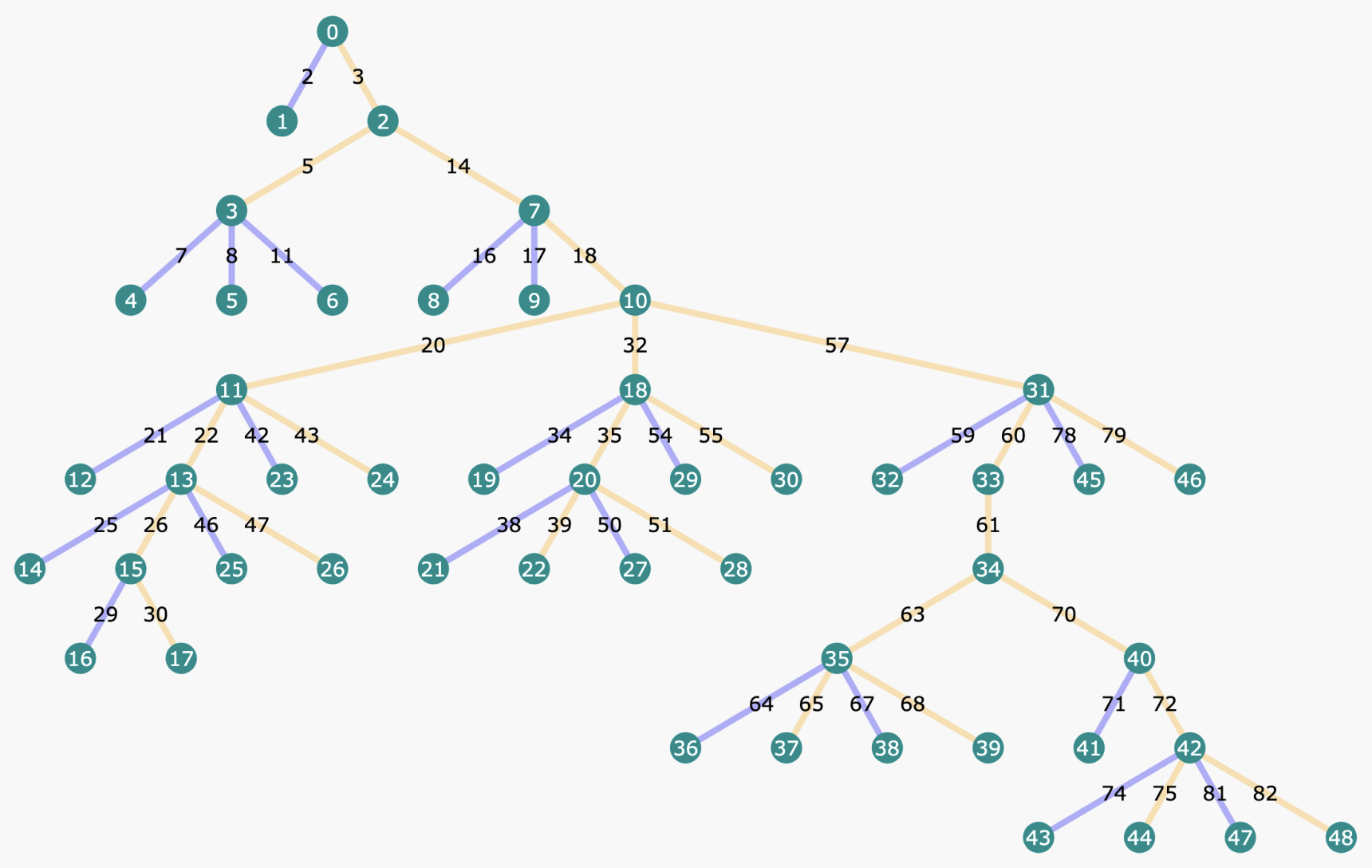

Improve Mathematical Reasoning in Language Models by Automated Process Supervision

- This paper from Luo et al. from Google DeepMind introduces a novel approach to enhance the mathematical reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs) through automated process supervision, focusing on intermediate reasoning steps rather than just final outcomes. Traditional techniques like Outcome Reward Models (ORM) verify the final answer’s correctness, but these models do not reward or penalize the intermediate steps, leading to challenges in solving complex multi-step reasoning tasks such as mathematical problem solving.

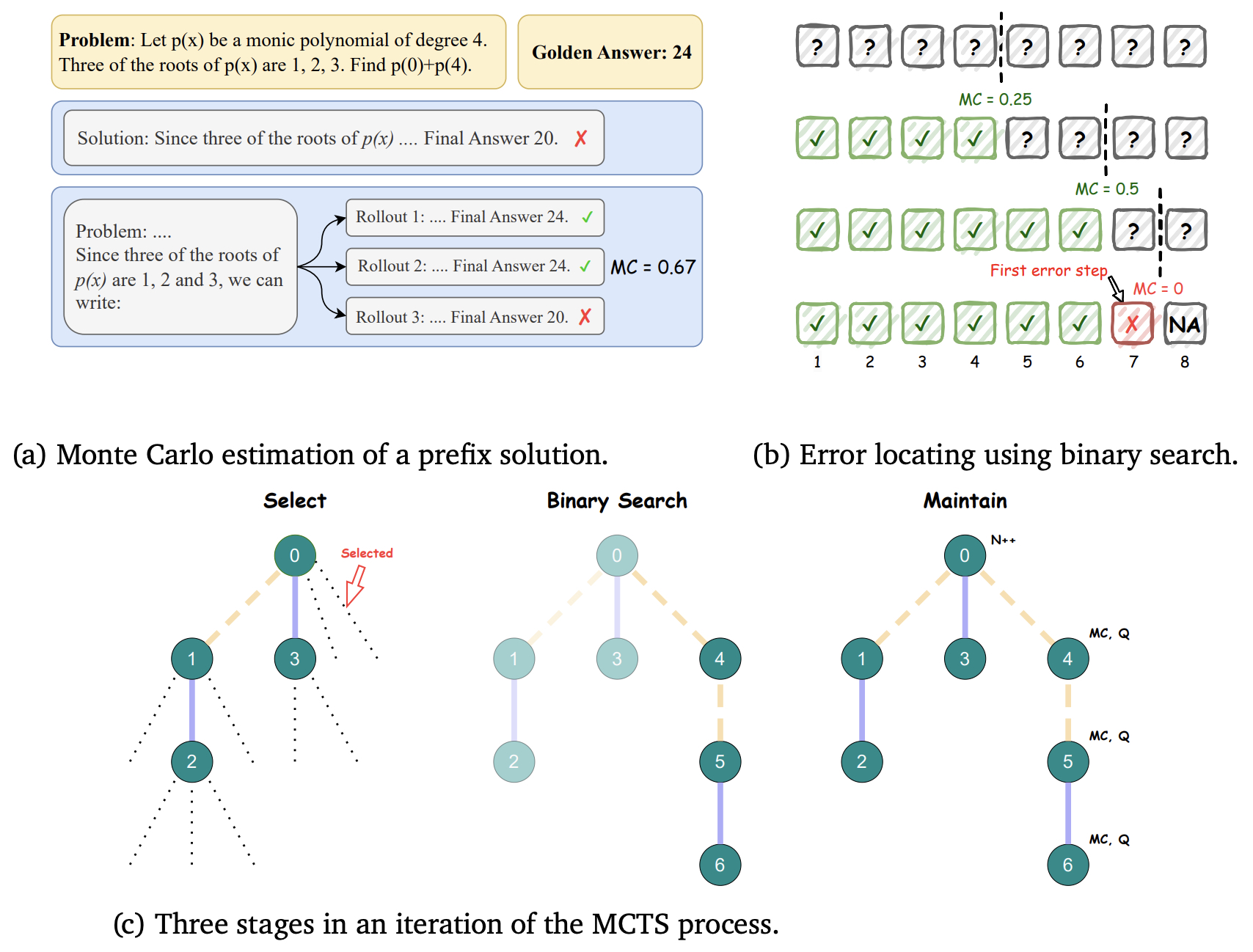

- The authors propose a new divide-and-conquer Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm, named OmegaPRM, for the efficient collection of process supervision data. OmegaPRM improves upon previous methods by utilizing a binary search technique to locate errors in the chain of thought, identifying the first error in a reasoning path. This method ensures a balanced collection of positive and negative examples, leading to high-quality data collection.

- The implementation of OmegaPRM allows the automatic generation of over 1.5 million process supervision annotations, which are used to train a Process Reward Model (PRM). These annotations are generated without human intervention, making the process both cost-effective and scalable. The PRM, when integrated with a weighted self-consistency algorithm, achieves a 69.4% success rate on the MATH benchmark, which is a significant 36% relative improvement over the base model performance of 51%.

- The following figure from the paper shows an example tree structure built with our proposed OmegaPRM algorithm. Each node in the tree indicates a state of partial chain-of-thought solution, with information including accuracy of rollouts and other statistics. Each edge indicates an action, i.e., a reasoning step, from the last state. Yellow edges are correct steps and blue edges are wrong.

- Key implementation details include:

- Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS): A tree is built for each mathematical question, with nodes representing intermediate reasoning steps. The binary search efficiently narrows down to the first incorrect step by performing rollouts at each stage.

- Tree Structure: Each node stores statistics, such as visit counts and Monte Carlo estimations, to guide future rollouts. This structure enables reuse of rollouts, reducing computational redundancy and enhancing the training data collection efficiency.

- PRM Training: The PRM is trained using pointwise soft labels derived from the Monte Carlo rollouts. The soft label approach provides better performance compared to hard labels and pairwise loss functions, achieving 70.1% accuracy in classifying per-step correctness.

- Data Generation: The PRM was trained on the MATH dataset, generating process annotations using OmegaPRM’s binary search method. This process reduced the number of policy calls while maintaining high-quality annotations.

- The following figure from the paper shows an illustration of the process supervision rollouts, Monte Carlo estimation using binary search and the MCTS process. (a) An example of Monte Carlo estimation of a prefix solution. Two out of the three rollouts are correct, producing the Monte Carlo estimation \(\operatorname{MC}\left(q, x_{1: t}\right)=2 / 3 \approx 0.67\). (b) An example of error locating using binary search. The first error step is located at the \(7^{\text {th }}\) step after three divide-and-rollouts, where the rollout positions are indicated by the vertical dashed lines. (c) The MCTS process. The dotted lines in Select stage represent the available rollouts for binary search. The bold colored edges represent steps with correctness estimations. The yellow color indicates a correct step, i.e., with a preceding state \(s\) that \(\mathrm{MC}(s)>0\) and the blue color indicates an incorrect step, i.e., with $$\mathrm{MC}(s)=0$. The number of dashes in each colored edge indicates the number of steps.

- The paper also highlights the cost-effectiveness of the OmegaPRM approach, as it automates the collection of process supervision data without human annotators, overcoming the limitations of previous methods that required expensive and labor-intensive human annotations. The resulting PRM significantly improves the reasoning accuracy of LLMs in multi-step mathematical tasks.

Chain-of-Thought Reasoning without Prompting

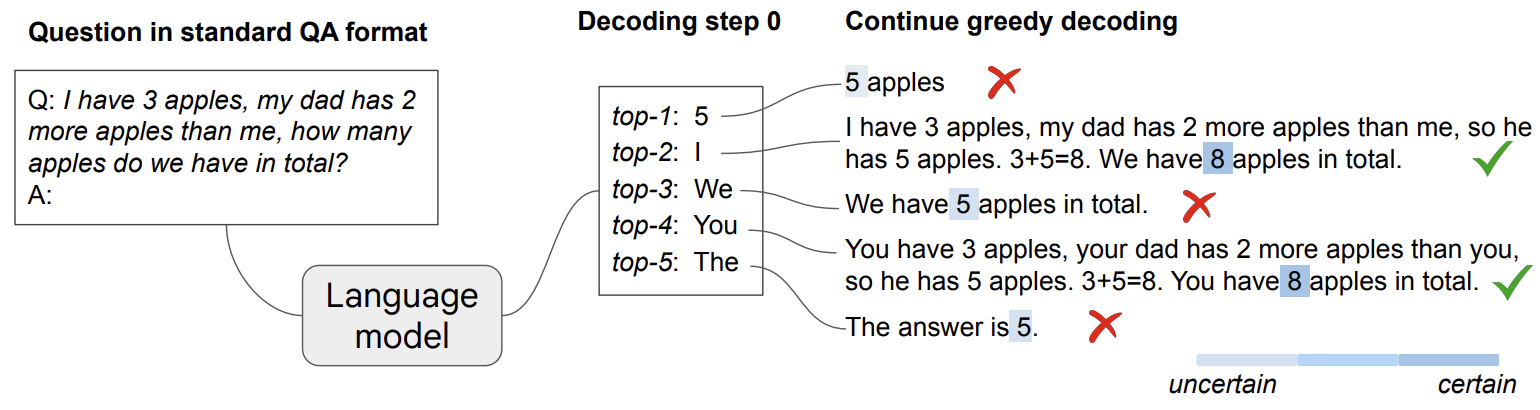

- This paper by Wang and Zhou from Google DeepMind investigates an alternative approach to elicit reasoning capabilities from large language models (LLMs) without the need for prompting techniques such as few-shot or zero-shot chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting. The key focus is on altering the decoding process to reveal inherent CoT reasoning paths within the models, avoiding the conventional reliance on manual prompt engineering.

- The authors demonstrate that by adjusting the decoding procedure, particularly moving away from greedy decoding to exploring top-\(k\) alternative tokens, it is possible to uncover CoT paths that the model naturally possesses. This method, termed CoT-decoding, effectively bypasses the limitations of standard prompting strategies and instead emphasizes a more task-agnostic way of assessing LLMs’ intrinsic reasoning capabilities.

- The following figure from the paper shows an illustration of CoT-decoding. Pre-trained LLMs are capable of inherent reasoning without prompting by considering alternative top-\(k\) tokens, rather than solely relying on the top-1 greedy decoding path. Moreover, these models tend to display higher confidence in decoding the final answer (indicated by a darker shaded color) when a CoT reasoning path is present.

- Technical Contributions:

- The authors show that when alternative decoding paths (top-\(k\) tokens) are considered, CoT reasoning paths often emerge naturally. This reveals reasoning capabilities that are typically hidden when models rely on the standard greedy decoding path.

- The presence of CoT in a decoding path correlates with a higher confidence in the final decoded answer. This confidence measure can be leveraged to differentiate between CoT and non-CoT paths.

- The method enables LLMs to solve reasoning tasks such as mathematical problems and commonsense reasoning more effectively compared to using prompting methods or greedy decoding alone.

- Implementation Details:

- CoT-decoding: This involves generating multiple alternative decoding paths by selecting the top-\(k\) tokens at each decoding step. After generating the paths, the model’s confidence in each path is evaluated based on the difference between the top two token probabilities in the final answer. This probability difference helps identify the most reliable CoT paths.

- The method is tested on various reasoning benchmarks such as GSM8K (math reasoning) and commonsense tasks (e.g., year parity questions). For example, in a mathematical task, a correct CoT path was found by selecting alternative decoding paths that consider intermediate steps, such as calculating the price of items and applying discounts sequentially, rather than providing a direct answer.

- The authors implemented CoT-decoding across several language models, including PaLM-2 and Mistral-7B. Across these models, CoT-decoding consistently yielded significant accuracy improvements over greedy decoding in tasks that require multi-step reasoning.

- The paper also explores the effect of different values for top-\(k\), showing that higher values generally improve model performance by increasing the likelihood of finding the correct reasoning paths.

- Experimental Results:

- CoT-decoding yielded a significant accuracy boost compared to greedy decoding, particularly on complex reasoning tasks. For example, on GSM8K, CoT-decoding improved accuracy from 9.9% to 25.1% on the Mistral-7B model, showcasing the effectiveness of this approach.

- The method partially closes the performance gap between pre-trained and instruction-tuned models. For instance, CoT-decoding improved the pre-trained PaLM-2 large model’s accuracy to levels close to that of instruction-tuned models without requiring any additional supervised data.

- This work presents a significant step forward in understanding LLMs’ intrinsic reasoning abilities without relying on human intervention through prompt engineering, making it easier to evaluate and harness these capabilities across a broader range of tasks.

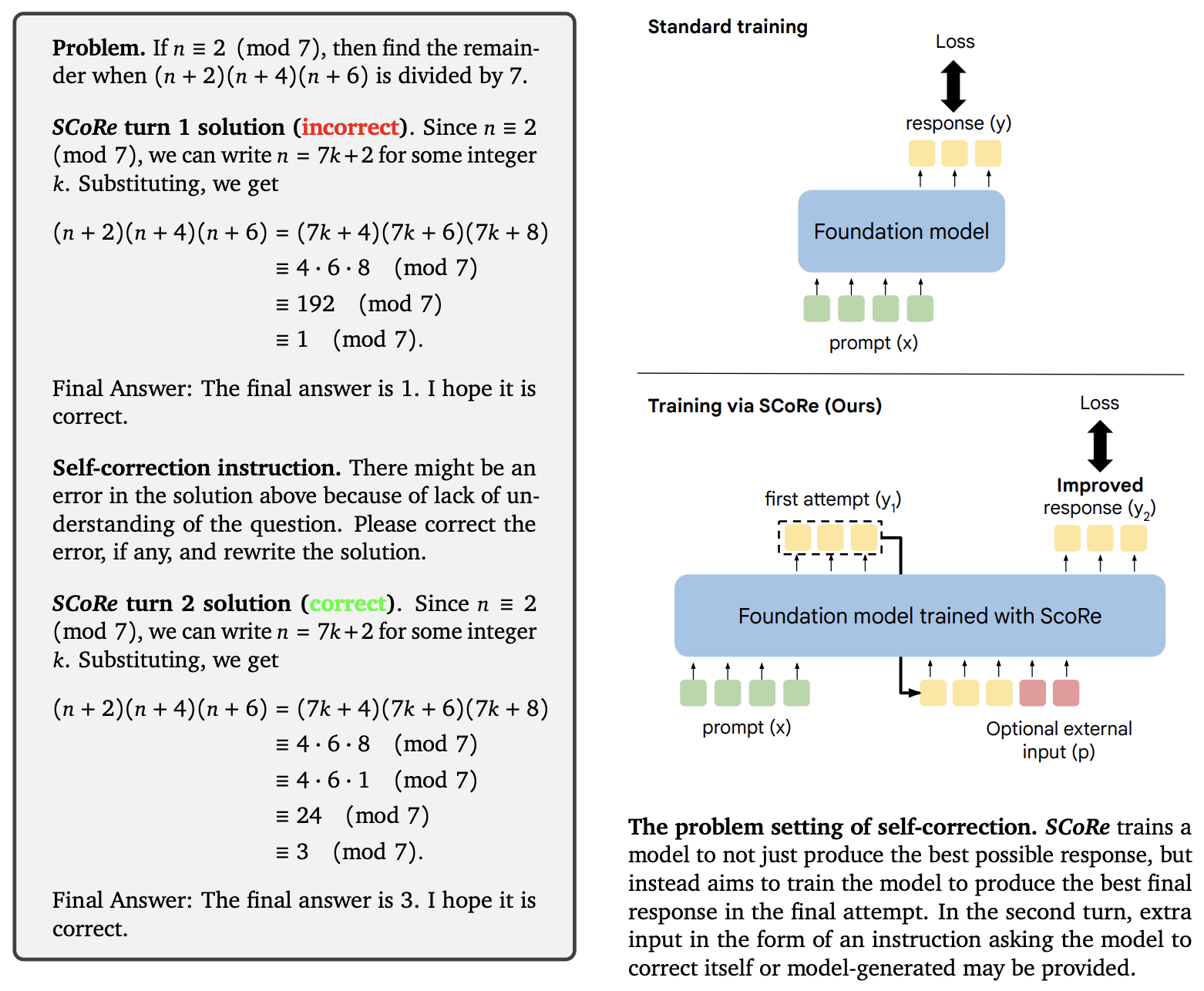

Training Language Models to Self-Correct via Reinforcement Learning

- This paper by Kumar et al. from Google DeepMind introduces SCoRe, a novel multi-turn online reinforcement learning (RL) approach that enhances LLMs’ intrinsic self-correction capabilities by training on self-generated data. Unlike previous self-correction methods that require multiple models or external supervision, SCoRe is designed to operate without any oracle feedback, relying entirely on data generated by the model itself.

- The authors first highlight the limitations of traditional supervised fine-tuning (SFT) approaches, which suffer from a distribution mismatch between training data and model outputs. These approaches often bias the model towards minimal edits that fail to generalize well to unseen problems, leading to ineffective self-correction. In response, SCoRe addresses these issues through multi-turn RL, allowing the model to iteratively refine its outputs across multiple attempts.

- The SCoRe method is implemented in two distinct stages:

- Stage I: Initialization – The model is fine-tuned to produce high-reward second-attempt responses while constraining its first attempt to remain close to the base model’s outputs. This initialization is critical in preventing collapse into trivial strategies like minimal edits.

- Stage II: Multi-turn RL with Reward Shaping – The RL training optimizes both the first and second attempts, with an emphasis on improving from the first to the second attempt. A reward shaping mechanism is introduced to amplify self-correction behaviors by providing bonus rewards for meaningful improvements between attempts.

- The following figure from the paper shows an example trace and the problem setting of self-correction.

- Key components of the implementation include:

- On-policy RL: SCoRe uses on-policy policy gradient methods to optimize for self-correction, ensuring that the model learns from its own mistakes and adapts to its own response distribution.

- Reward Shaping: The model receives additional rewards for making corrections that change an incorrect response to correct, encouraging it to explore self-correction strategies.

- KL-Divergence Regularization: The model’s first attempt is constrained via KL-divergence to stay close to the base model’s outputs, avoiding drastic changes that could degrade initial performance.

- The approach was tested on two key tasks: mathematical reasoning (using the MATH dataset) and coding (using the HumanEval and MBPP datasets). SCoRe demonstrated significant improvements over baseline models, achieving a 15.6% gain in self-correction accuracy on MATH and a 9.1% improvement on coding benchmarks. Importantly, the model improved not only in its ability to correct mistakes but also in maintaining correct responses across attempts.

- In terms of evaluation, SCoRe’s success was measured using metrics such as accuracy at each attempt (t1 and t2), the net improvement between attempts (Δ(t1, t2)), and the frequency of problems corrected in subsequent attempts. SCoRe outperformed other approaches by substantially reducing the number of correct answers that became incorrect in the second attempt and improving the rate of incorrect-to-correct transformations.

- The paper also provides ablation studies demonstrating the importance of each component in the SCoRe pipeline, highlighting the necessity of multi-turn training and reward shaping in achieving effective self-correction behavior.

- In summary, SCoRe presents a robust solution to the problem of self-correction in LLMs by leveraging reinforcement learning techniques that focus on improving performance iteratively over multiple attempts.

Further Reading

References

Citation

If you found our work useful, please cite it as:

@article{Chadha2020DistilledOpenAIo1,

title = {OpenAI o1},

author = {Chadha, Aman and Jain, Vinija},

journal = {Distilled AI},

year = {2020},

note = {\url{https://vinija.ai}}

}