Primers • Fine-Tuning and Evaluating BERT

- Overview

- Setup

- Retrieve Dataset

- Inspect Dataset

- Smart Batching

- Fine-Tune BERT

collatefunction- Evaluate on Test Set

- Appendix

- Further Reading

- References

- Citation

Overview

- In this article, let’s go over how to fine-tune and evaluate BERT while dramatically increase BERT’s training time by creating batches of samples with different sequence lengths.

Setup

Install transformers

!pip install transformers

Helper Functions

- In many of our (long-running)

for-loops, we should print periodic progress updates. Typically people pick the update interval manually, but yoy may defined a helper function to make that choice as follows:

def good_update_interval(total_iters, num_desired_updates):

'''

This function will try to pick an intelligent progress update interval

based on the magnitude of the total iterations.

Parameters:

`total_iters` - The number of iterations in the for-loop.

`num_desired_updates` - How many times we want to see an update over the

course of the for-loop.

'''

# Divide the total iterations by the desired number of updates. Most likely

# this will be some ugly number.

exact_interval = total_iters / num_desired_updates

# The `round` function has the ability to round down a number to, e.g., the

# nearest thousandth: round(exact_interval, -3)

#

# To determine the magnitude to round to, find the magnitude of the total,

# and then go one magnitude below that.

# Get the order of magnitude of the total.

order_of_mag = len(str(total_iters)) - 1

# Our update interval should be rounded to an order of magnitude smaller.

round_mag = order_of_mag - 1

# Round down and cast to an int.

update_interval = int(round(exact_interval, -round_mag))

# Don't allow the interval to be zero!

if update_interval == 0:

update_interval = 1

return update_interval

- Helper function for formatting elapsed times as

hh:mm:ss:

import time

import datetime

def format_time(elapsed):

'''

Takes a time in seconds and returns a string hh:mm:ss

'''

# Round to the nearest second.

elapsed_rounded = int(round((elapsed)))

# Format as hh:mm:ss

return str(datetime.timedelta(seconds=elapsed_rounded))

Retrieve Dataset

Download Dataset Files

-

I’m sure there are many ways to retrieve this dataset–I’m using the TensorFlow Datasets library here as one easy way to do it.

-

Check out the documentation here

import tensorflow_datasets as tfds

# Download the train and test portions of the dataset.

train_data = tfds.load(name="imdb_reviews/plain_text", split="train")

test_data = tfds.load(name="imdb_reviews/plain_text", split="test")

INFO:absl:Overwrite dataset info from restored data version.

INFO:absl:Reusing dataset imdb_reviews (/root/tensorflow_datasets/imdb_reviews/plain_text/1.0.0)

INFO:absl:Constructing tf.data.Dataset for split train, from /root/tensorflow_datasets/imdb_reviews/plain_text/1.0.0

INFO:absl:Overwrite dataset info from restored data version.

INFO:absl:Reusing dataset imdb_reviews (/root/tensorflow_datasets/imdb_reviews/plain_text/1.0.0)

INFO:absl:Constructing tf.data.Dataset for split test, from /root/tensorflow_datasets/imdb_reviews/plain_text/1.0.0

Let’s examine the contents and datatypes contained in the dataset.

- Each sample has a label and text field.

train_data

- which outputs:

<DatasetV1Adapter shapes: {label: (), text: ()}, types: {label: tf.int64, text: tf.string}>

- Let’s pull the data out of TensorFlow’s icy grip, so we just have plain Python types :)

import numpy as np

train_text = []

train_labels = []

# Loop over the training set...

for ex in train_data.as_numpy_iterator():

# The text is a `bytes` object, decode to string.

train_text.append(ex['text'].decode())

# Cast the label from `np.int64` to `int`

train_labels.append(int(ex['label']))

test_text = []

test_labels = []

# Loop over the test set...

for ex in test_data.as_numpy_iterator():

# The text is a `bytes` object, decode to string.

test_text.append(ex['text'].decode())

# Cast the label from `np.int64` to `int`

test_labels.append(int(ex['label']))

# Print some stats.

print('{:,} Training Samples'.format(len(train_labels)))

print('{:,} Test Samples'.format(len(test_labels)))

print('Labels:', np.unique(train_labels))

- which outputs:

25,000 Training Samples

25,000 Test Samples

Labels: [0 1]

Inspect Dataset

Inspect Training Samples

- Lets print out a handful of samples at random.

import textwrap

import random

# Wrap text to 80 characters.

wrapper = textwrap.TextWrapper(width=80)

# Randomly choose some examples.

for i in range(3):

# Choose a random sample by index.

j = random.choice(range(len(train_text)))

# Print out the label and the text.

print('==== Label: {:} ===='.format(train_labels[j]))

print(wrapper.fill(train_text[j]))

print('')

- which outputs:

==== Label: 0 ====

Somewhere, on this site, someone wrote that to get the best version of the works

of Jane Austen, one should simply read them. I agree with that. However, we love

adaptations of great literature and the current writers' strike brings to mind

that without good writers, it's hard for actors to bring their roles to life.

The current version of Jane Austen's PERSUASION shows us what happens when you

don't have a good foundation in a well-written adaptation. This version does not

compare to the 1995 version with Amanda Root and Ciaran Hinds, which was well

acted and kept the essence of the era and the constraints on the characters

(with the exception of the bizarre parade & kissing in the street scene in

Bath). The 2007 version shows a twitty Anne who seems angst-ridden. The other

characters were not very developed which is a crime, considering how Austen

could paint such wonderful characters with some carefully chosen

understatements. The sequence of events that made sense in the novel were

completely tossed about, and Mrs. Smith, Anne's bedridden and impoverished

schoolmate is walking around in Bath - - twittering away, as many of the

characters seemed to do. The strength of character and the intelligence of

Captain Wentworth, which caused Anne to love him in the first place, didn't seem

to be written into the Rupert Penry-Jones' Wentworth. Ciaran Hinds had more

substance and was able to convey so much more with a look, than P-J was able to

do with his poses. All in all, the 2007 version was a disappointment. It seemed

to reduce the novel into a hand- wringing, costumed melodrama of debatable

worth. If they wanted to bring our modern emotional extravagances into Austen's

work, they should have done what they do with adaptations of Shakespeare: adapt

it to the present. At least "Bride & Prejudice" was taken out of the historical

& locational settings and was fun to watch, as was "Clueless". This wasn't

PERSUASION, but they didn't know what else to call it.

==== Label: 0 ====

It's difficult to put into words the almost seething hatred I have of this film.

But I'll try:<br /><br />Every other word was an expletive, the sex scenes were

uncomfortable, drugs were rampant and stereotyping was beyond the norm, if not

offensive to Italian-Americans.<br /><br />I'm not saying the acting was

terrible, because Leguizamo, Sorvino, Brody, Espisito et. al, performed well.

But...almost every character in the film I despised. Not since The Bonfire of

the Vanities have I disliked every character on screen.

==== Label: 0 ====

Take one look at the cover of this movie, and you know right away that you are

not about to watch a landmark film. This is cheese filmmaking in every respect,

but it does have its moments. Despite the look of utter trash that the movie

gives, the story is actually interesting at some points, although it is

undeniably pulled along mainly by the cheerleading squads' shower scenes and sex

scenes with numerous personality-free boyfriends. The acting is awful and the

director did little more than point and shoot, which is why the extensive amount

of nudity was needed to keep the audience's attention.<br /><br />In The Nutty

Professor, a hopelessly geeky professor discovers a potion that can turn him

into a cool and stylish womanizer, whereas in The Invisible Maniac, a mentally

damaged professor discovers a potion that can make him invisible, allowing him

to spy on (and kill, for some reason) his students. Boring fodder. Don't expect

any kind of mental stimulation from this, and prepare yourself for shrill and

enormously overdone maniacal laughter which gets real annoying real quick...

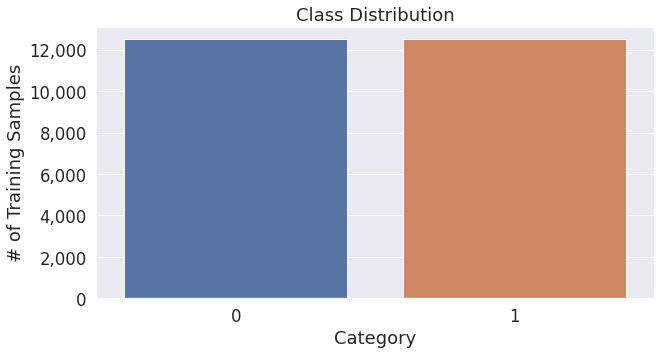

- Let’s also check out the classes and their balance.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import numpy as np

sns.set(style='darkgrid')

# Increase the plot size and font size.

sns.set(font_scale=1.5)

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (10,5)

# Plot the number of tokens of each length.

ax = sns.countplot(train_labels)

# Add labels

plt.title('Class Distribution')

plt.xlabel('Category')

plt.ylabel('# of Training Samples')

# Add thousands separators to the y-axis labels.

import matplotlib as mpl

ax.yaxis.set_major_formatter(mpl.ticker.StrMethodFormatter('{x:,.0f}'))

plt.show()

- The plot below shows the class balance in IMDB’s movie reviews:

Smart Batching

-

In this section, we will prepare our training set into these smart batches.

-

Note that we’ve also defined a

make_smart_batchesfunction towards the end which performs all of these steps. We’ll use that function to prepare the test set, and you could use that function in your own applications for both the training and test sets.

Load Tokenizer

- We’ll use the uncased version of BERT-base.

from transformers import BertTokenizer

# Load the BERT tokenizer.

print('Loading BERT tokenizer...')

tokenizer = BertTokenizer.from_pretrained('bert-base-uncased', do_lower_case=True)

- which outputs:

Loading BERT tokenizer...

Tokenize Without Padding

Peak GPU Memory Use

-

Even when applying smart batching, we may still want to truncate our inputs to a certain maximum length. BERT requires a lot of GPU memory, and it’s quite possible for the GPU to not be able to process a batch with too many samples in it and / or too long of sequences.

-

Smart batching means most of our batches will naturally have shorter sequence lengths and not require too much memory. However, all it takes is one batch that’s too long to fit on the GPU, and our training will fail!

-

In other words, we still have to be concerned with our “peak” memory usage, and it still likely makes sense to truncate to something lower than 512, even with smart batching.

max_len = 400

Tokenize, but don’t pad

-

We’re going to start by tokenizing all of the samples and mapping the tokens to their IDs.

-

We’re also going to truncate the sequences to our chosen

max_len, and we’re going to add the special tokens. -

But we are not padding yet! We don’t know what lengths to pad the sequences too until after we’ve grouped them into batches.

full_input_ids = []

labels = []

# Tokenize all training examples

print('Tokenizing {:,} training samples...'.format(len(train_text)))

# Choose an interval on which to print progress updates.

update_interval = good_update_interval(total_iters=len(train_text), num_desired_updates=10)

# For each training example...

for text in train_text:

# Report progress.

if ((len(full_input_ids) % update_interval) == 0):

print(' Tokenized {:,} samples.'.format(len(full_input_ids)))

# Tokenize the sentence.

input_ids = tokenizer.encode(text=text, # Movie review text

add_special_tokens=True, # Do add specials.

max_length=max_len, # Do truncate to `max_len`

truncation=True, # Do truncate!

padding=False) # Don't pad!

# Add the tokenized result to our list.

full_input_ids.append(input_ids)

print('DONE.')

print('{:>10,} samples'.format(len(full_input_ids)))

- which outputs:

Tokenizing 25,000 training samples...

Tokenized 0 samples.

Tokenized 2,000 samples.

Tokenized 4,000 samples.

Tokenized 6,000 samples.

Tokenized 8,000 samples.

Tokenized 10,000 samples.

Tokenized 12,000 samples.

Tokenized 14,000 samples.

Tokenized 16,000 samples.

Tokenized 18,000 samples.

Tokenized 20,000 samples.

Tokenized 22,000 samples.

Tokenized 24,000 samples.

DONE.

25,000 samples

Sort by length

-

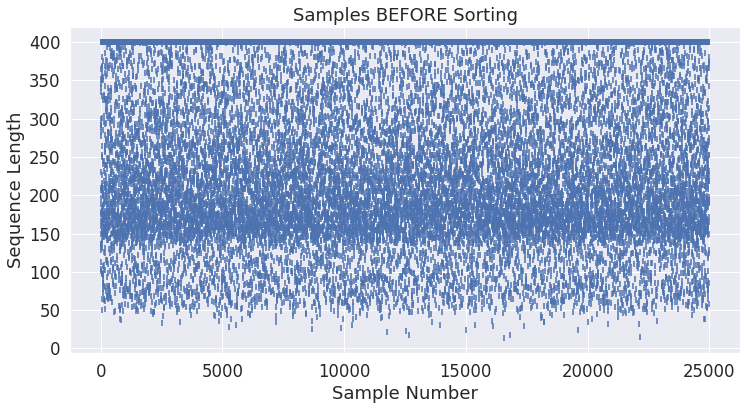

Before we sort the samples by length, let’s look at the lengths of the samples in their original, unsorted order.

-

The below plot simply confirms that the sample lengths do vary significantly, and that they are unsorted.

# Get all of the lengths.

unsorted_lengths = [len(x) for x in full_input_ids]

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Use plot styling from seaborn.

sns.set(style='darkgrid')

# Increase the plot size and font size.

sns.set(font_scale=1.5)

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12,6)

plt.scatter(range(0, len(unsorted_lengths)), unsorted_lengths, marker="|")

plt.xlabel('Sample Number')

plt.ylabel('Sequence Length')

plt.title('Samples BEFORE Sorting')

plt.show()

- The following plot shows samples before sorting:

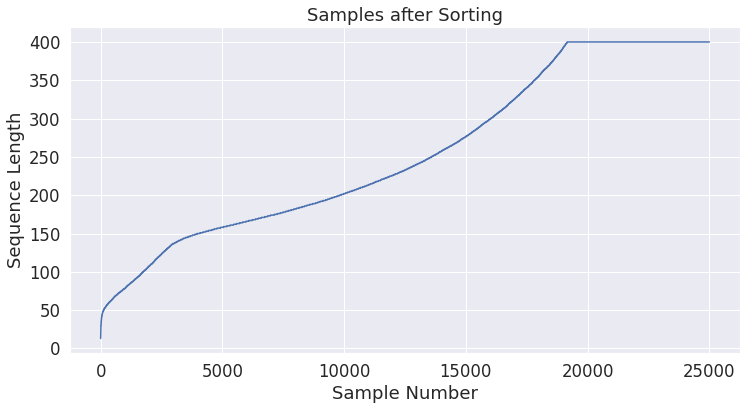

- Now we’ll sort the examples by length so that we can create batches with equal (or at least similar) lengths.

# Sort the two lists together by the length of the input sequence.

train_samples = sorted(zip(full_input_ids, train_labels), key=lambda x: len(x[0]))

train_samplesis now a list of tuples of (input_ids, label):

train_samples[0]

- which outputs:

([101, 2023, 3185, 2003, 6659, 2021, 2009, 2038, 2070, 2204, 3896, 1012, 102],

0)

- Now let’s check out the shortest/longest sample:

print('Shortest sample:', len(train_samples[0][0]))

print('Longest sample:', len(train_samples[-1][0]))

- which outputs:

Shortest sample: 13

Longest sample: 400

- Let’s generate the same plot again, now that the samples are sorted by length.

# Get the new list of lengths after sorting.

sorted_lengths = [len(s[0]) for s in train_samples]

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Use plot styling from seaborn.

sns.set(style='darkgrid')

# Increase the plot size and font size.

sns.set(font_scale=1.5)

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12,6)

plt.plot(range(0, len(sorted_lengths)), sorted_lengths)

plt.xlabel('Sample Number')

plt.ylabel('Sequence Length')

plt.title('Samples after Sorting')

plt.show()

- The following plot shows samples after sorting:

Random Batch Selection

- Choose our batch size.

batch_size = 16

-

Now we’re ready to select our batches.

-

The strategy used here comes from Michaël Benesty’s code (also, blog post is here), in his

build_batchesfunction. -

Rather than dividing the batches up in order, we will still add a degree of randomness to our selection.

-

Here’s the process:

- Pick a random starting point in the (sorted!) list of samples.

- Grab a contiguous batch of samples starting from that point.

- Delete those samples from the list, and repeat until all of the samples have been grabbed.

-

This will result in some fragmentation of the list, which means it won’t be quite as efficient as if we just sliced up the batches in sorted order.

-

The benefit is that our path through the training set can still have a degree of randomness. Also, given the distribution of lengths that we saw in the previous section (lots of samples with similar lengths), the fragmentation problem should be pretty minor!

import random

# List of batches that we'll construct.

batch_ordered_sentences = []

batch_ordered_labels = []

print('Creating training batches of size {:}'.format(batch_size))

# Loop over all of the input samples...

while len(train_samples) > 0:

# Report progress.

if ((len(batch_ordered_sentences) % 500) == 0):

print(' Selected {:,} batches.'.format(len(batch_ordered_sentences)))

# `to_take` is our actual batch size. It will be `batch_size` until

# we get to the last batch, which may be smaller.

to_take = min(batch_size, len(train_samples))

# Pick a random index in the list of remaining samples to start

# our batch at.

select = random.randint(0, len(train_samples) - to_take)

# Select a contiguous batch of samples starting at `select`.

batch = train_samples[select:(select + to_take)]

# Each sample is a tuple--split them apart to create a separate list of

# sequences and a list of labels for this batch.

batch_ordered_sentences.append([s[0] for s in batch])

batch_ordered_labels.append([s[1] for s in batch])

# Remove these samples from the list.

del train_samples[select:select + to_take]

print('\n DONE - {:,} batches.'.format(len(batch_ordered_sentences)))

- which outputs:

Creating training batches of size 16

Selected 0 batches.

Selected 500 batches.

Selected 1,000 batches.

Selected 1,500 batches.

DONE - 1,563 batches.

Add Padding

-

We’ve created our batches, but many of them will contain sequences of different lengths. In order to leverage the GPUs parallel processing of batches, all of the sequences within a batch need to be the same length.

-

This means we need to do some padding!

-

We’ll also create our attention masks here, and cast everything to PyTorch tensors in preparation for our fine-tuning step.

import torch

py_inputs = []

py_attn_masks = []

py_labels = []

# For each batch...

for (batch_inputs, batch_labels) in zip(batch_ordered_sentences, batch_ordered_labels):

# New version of the batch, this time with padded sequences and now with

# attention masks defined.

batch_padded_inputs = []

batch_attn_masks = []

# First, find the longest sample in the batch.

# Note that the sequences do currently include the special tokens!

max_size = max([len(sen) for sen in batch_inputs])

#print('Max size:', max_size)

# For each input in this batch...

for sen in batch_inputs:

# How many pad tokens do we need to add?

num_pads = max_size - len(sen)

# Add `num_pads` padding tokens to the end of the sequence.

padded_input = sen + [tokenizer.pad_token_id]*num_pads

# Define the attention mask--it's just a `1` for every real token

# and a `0` for every padding token.

attn_mask = [1] * len(sen) + [0] * num_pads

# Add the padded results to the batch.

batch_padded_inputs.append(padded_input)

batch_attn_masks.append(attn_mask)

# Our batch has been padded, so we need to save this updated batch.

# We also need the inputs to be PyTorch tensors, so we'll do that here.

py_inputs.append(torch.tensor(batch_padded_inputs))

py_attn_masks.append(torch.tensor(batch_attn_masks))

py_labels.append(torch.tensor(batch_labels))

- Now that our data is ready, we can calculate the total number of tokens in the training data after using smart batching.

# Get the new list of lengths after sorting.

padded_lengths = []

# For each batch...

for batch in py_inputs:

# For each sample...

for s in batch:

# Record its length.

padded_lengths.append(len(s))

# Sum up the lengths to the get the total number of tokens after smart batching.

smart_token_count = np.sum(padded_lengths)

# To get the total number of tokens in the dataset using fixed padding, it's

# as simple as the number of samples times our `max_len` parameter (that we

# would pad everything to).

fixed_token_count = len(train_text) * max_len

# Calculate the percentage reduction.

prcnt_reduced = (fixed_token_count - smart_token_count) / float(fixed_token_count)

print('Total tokens:')

print(' Fixed Padding: {:,}'.format(fixed_token_count))

print(' Smart Batching: {:,} ({:.1%} less)'.format(smart_token_count, prcnt_reduced))

- which outputs:

Total tokens:

Fixed Padding: 10,000,000

Smart Batching: 6,381,424 (36.2% less)

- We’ll see at the end that this reduction in token count corresponds well to the reduction in training time!

Old Approach - Fixed Padding

- To see how BERT does on the benchmark without smart batching, you can run the following code instead of the above sections: Tokenize Without Padding, Sort by length, Random Batch Selection and Add Padding.

use_fixed_padding = False

if use_fixed_padding:

# Specify batch_size and truncation length.

batch_size = 16

max_len = 400

# Tokenize all training examples

print('Tokenizing {:,} training samples...'.format(len(train_text)))

# Tokenize all of the sentences and map the tokens to thier word IDs.

batches_input_ids = []

batches_attention_masks = []

batches_labels = []

update_interval = batch_size * 150

# For every sentence...

for i in range(0, len(train_text), batch_size):

# Report progress.

if ((i % update_interval) == 0):

print(' Tokenized {:,} samples.'.format(i))

# `encode_plus` will:

# (1) Tokenize the sentence.

# (2) Prepend the `[CLS]` token to the start.

# (3) Append the `[SEP]` token to the end.

# (4) Map tokens to their IDs.

# (5) Pad or truncate the sentence to `max_length`

# (6) Create attention masks for `[PAD]` tokens.

encoded_dict = tokenizer.batch_encode_plus(

train_text[i:i+batch_size], # Batch of sentences to encode.

add_special_tokens = True, # Add '[CLS]' and '[SEP]'

max_length = 400, # Pad & truncate all sentences.

padding = 'max_length', # Pad all to the `max_length` parameter.

truncation = True,

return_attention_mask = True, # Construct attn. masks.

return_tensors = 'pt', # Return pytorch tensors.

)

# Add the encoded sentence to the list.

batches_input_ids.append(encoded_dict['input_ids'])

# And its attention mask (simply differentiates padding from non-padding).

batches_attention_masks.append(encoded_dict['attention_mask'])

# Add the labels for the batch

batches_labels.append(torch.tensor(train_labels[i:i+batch_size]))

# Rename the final variable to match the rest of the code in this Notebook.

py_inputs = batches_input_ids

py_attn_masks = batches_attention_masks

py_labels = batches_labels

Fine-Tune BERT

Load Pre-Trained Model

-

We’ll use BERT-base-uncased for this example.

-

transformersdefines theseAutoclasses which will automatically select the correct class for the pre-trained model that you specified.

from transformers import AutoConfig

# Load the Config object, with an output configured for classification.

config = AutoConfig.from_pretrained(pretrained_model_name_or_path='bert-base-uncased',

num_labels=2)

print('Config type:', str(type(config)), '\n')

- which outputs:

HBox(children=(FloatProgress(value=0.0, description='Downloading', max=433.0, style=ProgressStyle(description_…

Config type: <class 'transformers.configuration_bert.BertConfig'>

- Now let’s load the pre-trained model using the config:

from transformers import AutoModelForSequenceClassification

# Load the pre-trained model for classification, passing in the `config` from

# above.

model = AutoModelForSequenceClassification.from_pretrained(

pretrained_model_name_or_path='bert-base-uncased',

config=config)

print('\nModel type:', str(type(model)))

- which outputs:

HBox(children=(FloatProgress(value=0.0, description='Downloading', max=440473133.0, style=ProgressStyle(descri…

WARNING:transformers.modeling_utils:Some weights of the model checkpoint at bert-base-uncased were not used when initializing BertForSequenceClassification: ['cls.predictions.bias', 'cls.predictions.transform.dense.weight', 'cls.predictions.transform.dense.bias', 'cls.predictions.decoder.weight', 'cls.seq_relationship.weight', 'cls.seq_relationship.bias', 'cls.predictions.transform.LayerNorm.weight', 'cls.predictions.transform.LayerNorm.bias']

- This IS expected if you are initializing BertForSequenceClassification from the checkpoint of a model trained on another task or with another architecture (e.g. initializing a BertForSequenceClassification model from a BertForPretraining model).

- This IS NOT expected if you are initializing BertForSequenceClassification from the checkpoint of a model that you expect to be exactly identical (initializing a BertForSequenceClassification model from a BertForSequenceClassification model).

WARNING:transformers.modeling_utils:Some weights of BertForSequenceClassification were not initialized from the model checkpoint at bert-base-uncased and are newly initialized: ['classifier.weight', 'classifier.bias']

You should probably TRAIN this model on a down-stream task to be able to use it for predictions and inference.

Model type: <class 'transformers.modeling_bert.BertForSequenceClassification'>

-

Connect to the GPU and load our model onto it.

-

It’s worth taking note of which GPU you’re given. The Tesla P100 is much faster, for example, than the Tesla K80.

import torch

print('\nLoading model to GPU...')

device = torch.device('cuda')

print(' GPU:', torch.cuda.get_device_name(0))

desc = model.to(device)

print(' DONE.')

- which outputs:

Loading model to GPU...

GPU: Tesla K80

DONE.

Optimizer & Learning Rate Scheduler

- Set up our optimizer and learning rate scheduler for training.

from transformers import AdamW

# Note: AdamW is a class from the huggingface library (as opposed to pytorch)

# The 'W' likely stands for 'Weight Decay fix"

optimizer = AdamW(model.parameters(),

lr = 5e-5, # This is the value Michael used.

eps = 1e-8 # args.adam_epsilon - default is 1e-8.

)

from transformers import get_linear_schedule_with_warmup

# Number of training epochs. We choose to train for one epoch simply because the training

# time is long. More epochs may improve the model's accuracy.

epochs = 1

# Total number of training steps is [number of batches] x [number of epochs].

# Note that it's the number of *batches*, not *samples*!

total_steps = len(py_inputs) * epochs

# Create the learning rate scheduler.

scheduler = get_linear_schedule_with_warmup(optimizer,

num_warmup_steps = 0, # Default value in run_glue.py

num_training_steps = total_steps)

Training Loop

-

In previous examples, we’ve made use of the PyTorch

DatasetandDataLoaderclasses, but because of the smart batching we’re not using them in this Notebook. However, check out the section below on how to use thecollatefunction with a standardDataLoaderpipeline. However, check out the section below on how to use thecollatefunction with a standardDataLoaderpipeline. -

Note: If you have modified the code here to run for more than one epoch, you’ll need the

make_smart_batchesfunction defined in the make_smart_batches section. -

We’re ready to kick off the training!

import random

import numpy as np

# This training code is based on the `run_glue.py` script here:

# https://github.com/huggingface/transformers/blob/5bfcd0485ece086ebcbed2d008813037968a9e58/examples/run_glue.py#L128

# Set the seed value all over the place to make this reproducible.

seed_val = 321

random.seed(seed_val)

np.random.seed(seed_val)

torch.manual_seed(seed_val)

torch.cuda.manual_seed_all(seed_val)

# We'll store a number of quantities such as training and validation loss,

# validation accuracy, and timings.

training_stats = []

# Update every `update_interval` batches.

update_interval = good_update_interval(total_iters=len(py_inputs), num_desired_updates=10)

# Measure the total training time for the whole run.

total_t0 = time.time()

# For each epoch...

for epoch_i in range(0, epochs):

# ========================================

# Training

# ========================================

# Perform one full pass over the training set.

print("")

print('======== Epoch {:} / {:} ========'.format(epoch_i + 1, epochs))

# At the start of each epoch (except for the first) we need to re-randomize

# our training data.

if epoch_i > 0:

# Use our `make_smart_batches` function (from 6.1.) to re-shuffle the

# dataset into new batches.

(py_inputs, py_attn_masks, py_labels) = make_smart_batches(train_text, train_labels, batch_size)

print('Training on {:,} batches...'.format(len(py_inputs)))

# Measure how long the training epoch takes.

t0 = time.time()

# Reset the total loss for this epoch.

total_train_loss = 0

# Put the model into training mode. Don't be misled--the call to

# `train` just changes the *mode*, it doesn't *perform* the training.

# `dropout` and `batchnorm` layers behave differently during training

# vs. test (source: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/51433378/what-does-model-train-do-in-pytorch)

model.train()

# For each batch of training data...

for step in range(0, len(py_inputs)):

# Progress update every, e.g., 100 batches.

if step % update_interval == 0 and not step == 0:

# Calculate elapsed time in minutes.

elapsed = format_time(time.time() - t0)

# Calculate the time remaining based on our progress.

steps_per_sec = (time.time() - t0) / step

remaining_sec = steps_per_sec * (len(py_inputs) - step)

remaining = format_time(remaining_sec)

# Report progress.

print(' Batch {:>7,} of {:>7,}. Elapsed: {:}. Remaining: {:}'.format(step, len(py_inputs), elapsed, remaining))

# Copy the current training batch to the GPU using the `to` method.

b_input_ids = py_inputs[step].to(device)

b_input_mask = py_attn_masks[step].to(device)

b_labels = py_labels[step].to(device)

# Always clear any previously calculated gradients before performing a

# backward pass.

model.zero_grad()

# Perform a forward pass (evaluate the model on this training batch).

# The call returns the loss (because we provided labels) and the

# "logits"--the model outputs prior to activation.

loss, logits = model(b_input_ids,

token_type_ids=None,

attention_mask=b_input_mask,

labels=b_labels)

# Accumulate the training loss over all of the batches so that we can

# calculate the average loss at the end. `loss` is a Tensor containing a

# single value; the `.item()` function just returns the Python value

# from the tensor.

total_train_loss += loss.item()

# Perform a backward pass to calculate the gradients.

loss.backward()

# Clip the norm of the gradients to 1.0.

# This is to help prevent the "exploding gradients" problem.

torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(model.parameters(), 1.0)

# Update parameters and take a step using the computed gradient.

# The optimizer dictates the "update rule"--how the parameters are

# modified based on their gradients, the learning rate, etc.

optimizer.step()

# Update the learning rate.

scheduler.step()

# Calculate the average loss over all of the batches.

avg_train_loss = total_train_loss / len(py_inputs)

# Measure how long this epoch took.

training_time = format_time(time.time() - t0)

print("")

print(" Average training loss: {0:.2f}".format(avg_train_loss))

print(" Training epcoh took: {:}".format(training_time))

# Record all statistics from this epoch.

training_stats.append(

{

'epoch': epoch_i + 1,

'Training Loss': avg_train_loss,

'Training Time': training_time,

}

)

print("")

print("Training complete!")

print("Total training took {:} (h:mm:ss)".format(format_time(time.time()-total_t0)))

- which outputs:

======== Epoch 1 / 1 ========

Training on 1,563 batches...

Batch 200 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:04:33. Remaining: 0:30:58

Batch 400 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:08:52. Remaining: 0:25:47

Batch 600 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:13:15. Remaining: 0:21:16

Batch 800 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:17:47. Remaining: 0:16:58

Batch 1,000 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:22:22. Remaining: 0:12:36

Batch 1,200 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:27:04. Remaining: 0:08:11

Batch 1,400 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:31:19. Remaining: 0:03:39

Average training loss: 0.25

Training epcoh took: 0:35:06

Training complete!

Total training took 0:35:06 (h:mm:ss)

collate function

- The

collate_fnargument to theDataLoaderclass receives a list of tuples if your__getitem__function from a Dataset subclass returns a tuple, or just a normal list if your Dataset subclass returns only one element. Its main objective is to create your batch without spending much time implementing it manually. Try to see it as a glue that you specify the way examples stick together in a batch. If you don’t use it, PyTorch only putbatch_sizeexamples together as you would using torch.stack (not exactly it, but it is simple like that). - Suppose for example, you want to create batches of a list of varying dimension tensors. The below code pads sequences with 0 until the maximum sequence size of the batch, that is why we need the

collate_fn, because a standard batching algorithm (simply usingtorch.stack) won’t work in this case, and we need to manually pad different sequences with variable length to the same size before creating the batch.

def collate_fn(data):

"""

data: is a list of tuples with (example, label, length)

where 'example' is a tensor of arbitrary shape

and label/length are scalars

"""

_, labels, lengths = zip(*data)

max_len = max(lengths)

n_ftrs = data[0][0].size(1)

features = torch.zeros((len(data), max_len, n_ftrs))

labels = torch.tensor(labels)

lengths = torch.tensor(lengths)

for i in range(len(data)):

j, k = data[i][0].size(0), data[i][0].size(1)

features[i] = torch.cat([data[i][0], torch.zeros((max_len - j, k))])

return features.float(), labels.long(), lengths.long()

- The function above is fed to the collate_fn param in the DataLoader, as this example:

DataLoader(toy_dataset, collate_fn=collate_fn, batch_size=5)

-

With this

collate_fnfunction, you always gonna have a tensor where all your examples have the same size. So, when you feed yourforward()function with this data, you need to use the length to get the original data back, to not use those meaningless zeros in your computation. -

For more, check out the PyTorch documentation.

Evaluate on Test Set

make_smart_batches()

- This function combines all of the steps from the “Smart Batching” section into a single (re-usable) function. You can use this in your own Notebook for applying smart batching to both your training and test sets.

def make_smart_batches(text_samples, labels, batch_size):

'''

This function combines all of the required steps to prepare batches.

'''

print('Creating Smart Batches from {:,} examples with batch size {:,}...\n'.format(len(text_samples), batch_size))

# =========================

# Tokenize & Truncate

# =========================

full_input_ids = []

# Tokenize all training examples

print('Tokenizing {:,} samples...'.format(len(labels)))

# Choose an interval on which to print progress updates.

update_interval = good_update_interval(total_iters=len(labels), num_desired_updates=10)

# For each training example...

for text in text_samples:

# Report progress.

if ((len(full_input_ids) % update_interval) == 0):

print(' Tokenized {:,} samples.'.format(len(full_input_ids)))

# Tokenize the sample.

input_ids = tokenizer.encode(text=text, # Text to encode.

add_special_tokens=True, # Do add specials.

max_length=max_len, # Do Truncate!

truncation=True, # Do Truncate!

padding=False) # DO NOT pad.

# Add the tokenized result to our list.

full_input_ids.append(input_ids)

print('DONE.')

print('{:>10,} samples\n'.format(len(full_input_ids)))

# =========================

# Select Batches

# =========================

# Sort the two lists together by the length of the input sequence.

samples = sorted(zip(full_input_ids, labels), key=lambda x: len(x[0]))

print('{:>10,} samples after sorting\n'.format(len(samples)))

import random

# List of batches that we'll construct.

batch_ordered_sentences = []

batch_ordered_labels = []

print('Creating batches of size {:}...'.format(batch_size))

# Choose an interval on which to print progress updates.

update_interval = good_update_interval(total_iters=len(samples), num_desired_updates=10)

# Loop over all of the input samples...

while len(samples) > 0:

# Report progress.

if ((len(batch_ordered_sentences) % update_interval) == 0 \

and not len(batch_ordered_sentences) == 0):

print(' Selected {:,} batches.'.format(len(batch_ordered_sentences)))

# `to_take` is our actual batch size. It will be `batch_size` until

# we get to the last batch, which may be smaller.

to_take = min(batch_size, len(samples))

# Pick a random index in the list of remaining samples to start

# our batch at.

select = random.randint(0, len(samples) - to_take)

# Select a contiguous batch of samples starting at `select`.

#print("Selecting batch from {:} to {:}".format(select, select+to_take))

batch = samples[select:(select + to_take)]

#print("Batch length:", len(batch))

# Each sample is a tuple--split them apart to create a separate list of

# sequences and a list of labels for this batch.

batch_ordered_sentences.append([s[0] for s in batch])

batch_ordered_labels.append([s[1] for s in batch])

# Remove these samples from the list.

del samples[select:select + to_take]

print('\n DONE - Selected {:,} batches.\n'.format(len(batch_ordered_sentences)))

# =========================

# Add Padding

# =========================

print('Padding out sequences within each batch...')

py_inputs = []

py_attn_masks = []

py_labels = []

# For each batch...

for (batch_inputs, batch_labels) in zip(batch_ordered_sentences, batch_ordered_labels):

# New version of the batch, this time with padded sequences and now with

# attention masks defined.

batch_padded_inputs = []

batch_attn_masks = []

# First, find the longest sample in the batch.

# Note that the sequences do currently include the special tokens!

max_size = max([len(sen) for sen in batch_inputs])

# For each input in this batch...

for sen in batch_inputs:

# How many pad tokens do we need to add?

num_pads = max_size - len(sen)

# Add `num_pads` padding tokens to the end of the sequence.

padded_input = sen + [tokenizer.pad_token_id]*num_pads

# Define the attention mask--it's just a `1` for every real token

# and a `0` for every padding token.

attn_mask = [1] * len(sen) + [0] * num_pads

# Add the padded results to the batch.

batch_padded_inputs.append(padded_input)

batch_attn_masks.append(attn_mask)

# Our batch has been padded, so we need to save this updated batch.

# We also need the inputs to be PyTorch tensors, so we'll do that here.

# Todo - Michael's code specified "dtype=torch.long"

py_inputs.append(torch.tensor(batch_padded_inputs))

py_attn_masks.append(torch.tensor(batch_attn_masks))

py_labels.append(torch.tensor(batch_labels))

print(' DONE.')

# Return the smart-batched dataset!

return (py_inputs, py_attn_masks, py_labels)

Load Test Dataset & Smart Batch

- Load the test dataset. This file has more columns, and contains rows for different languages (we’ll only select the French test samples).

# Use our new function to completely prepare our dataset.

(py_inputs, py_attn_masks, py_labels) = make_smart_batches(test_text, test_labels, batch_size)

- which outputs:

Creating Smart Batches from 25,000 examples with batch size 16...

Tokenizing 25,000 samples...

Tokenized 0 samples.

Tokenized 2,000 samples.

Tokenized 4,000 samples.

Tokenized 6,000 samples.

Tokenized 8,000 samples.

Tokenized 10,000 samples.

Tokenized 12,000 samples.

Tokenized 14,000 samples.

Tokenized 16,000 samples.

Tokenized 18,000 samples.

Tokenized 20,000 samples.

Tokenized 22,000 samples.

Tokenized 24,000 samples.

DONE.

25,000 samples

25,000 samples after sorting

Creating batches of size 16...

DONE - Selected 1,563 batches.

Padding out sequences within each batch...

DONE.

Evaluate

- With the test set prepared, we can apply our fine-tuned model to generate predictions on the test set.

# Prediction on test set

print('Predicting labels for {:,} test sentences...'.format(len(test_labels)))

# Tracking variables

predictions , true_labels = [], []

# Choose an interval on which to print progress updates.

update_interval = good_update_interval(total_iters=len(py_inputs), num_desired_updates=10)

# Measure elapsed time.

t0 = time.time()

# Put model in evaluation mode

model.eval()

# For each batch of training data...

for step in range(0, len(py_inputs)):

# Progress update every 100 batches.

if step % update_interval == 0 and not step == 0:

# Calculate elapsed time in minutes.

elapsed = format_time(time.time() - t0)

# Calculate the time remaining based on our progress.

steps_per_sec = (time.time() - t0) / step

remaining_sec = steps_per_sec * (len(py_inputs) - step)

remaining = format_time(remaining_sec)

# Report progress.

print(' Batch {:>7,} of {:>7,}. Elapsed: {:}. Remaining: {:}'.format(step, len(py_inputs), elapsed, remaining))

# Copy the batch to the GPU.

b_input_ids = py_inputs[step].to(device)

b_input_mask = py_attn_masks[step].to(device)

b_labels = py_labels[step].to(device)

# Telling the model not to compute or store gradients, saving memory and

# speeding up prediction

with torch.no_grad():

# Forward pass, calculate logit predictions

outputs = model(b_input_ids, token_type_ids=None,

attention_mask=b_input_mask)

logits = outputs[0]

# Move logits and labels to CPU

logits = logits.detach().cpu().numpy()

label_ids = b_labels.to('cpu').numpy()

# Store predictions and true labels

predictions.append(logits)

true_labels.append(label_ids)

print(' DONE.')

- which outputs:

Predicting labels for 25,000 test sentences...

Batch 200 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:01:32. Remaining: 0:10:27

Batch 400 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:03:03. Remaining: 0:08:53

Batch 600 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:04:35. Remaining: 0:07:21

Batch 800 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:06:05. Remaining: 0:05:48

Batch 1,000 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:07:37. Remaining: 0:04:17

Batch 1,200 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:09:08. Remaining: 0:02:46

Batch 1,400 of 1,563. Elapsed: 0:10:44. Remaining: 0:01:15

DONE.

- Now we can calculate the test set accuracy!

# Combine the results across the batches.

predictions = np.concatenate(predictions, axis=0)

true_labels = np.concatenate(true_labels, axis=0)

# Choose the label with the highest score as our prediction.

preds = np.argmax(predictions, axis=1).flatten()

# Calculate simple flat accuracy -- number correct over total number.

accuracy = (preds == true_labels).mean()

print('Accuracy: {:.3f}'.format(accuracy))

- which outputs:

Accuracy: 0.935

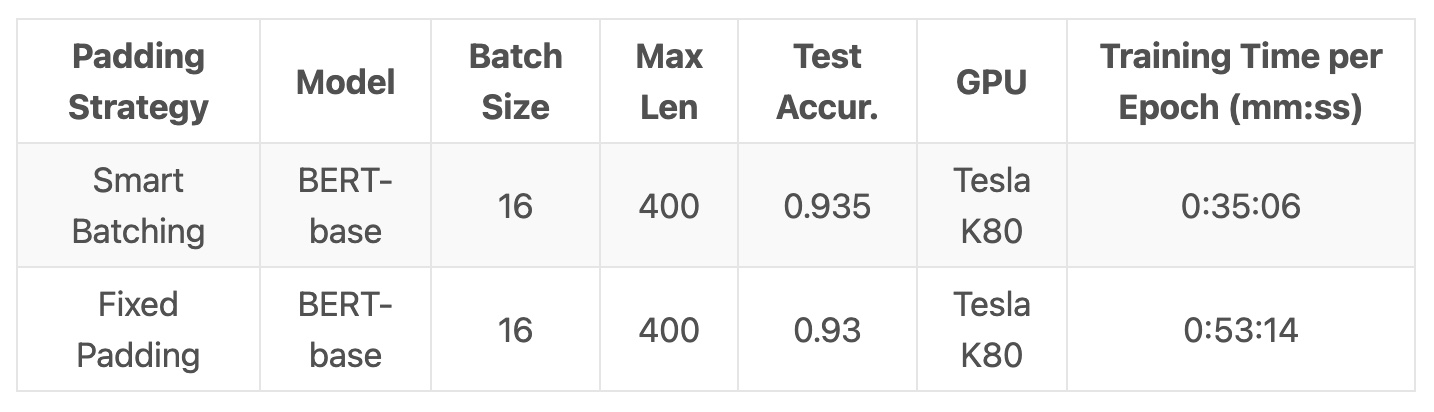

- Here are our results from running a single training epoch on a Tesla K80, comparing fixed-padding to smart batching.

- The fixed padding approach took 51.7% longer to train the model than Smart Batching!

Appendix

Smart Batching with batch_encode_plus and DataLoader

-

This section discusses how “smart batching” might be implemented in a more formal way with the PyTorch

DataLoaderclass and using the features currently available in huggingfacetransformers. -

In

transformers, thebatch_encode_plusfunction does have support for “Dynamic Padding”–it can automatically pad all of the samples in a batch out to match the longest sequence length in the batch. -

Check out the explanation given in this Warning in the source code, in tokenization_utils_base.py:

“The pad_to_max_length argument is deprecated and will be removed in a future version, use padding=True or padding=’longest’ to pad to the longest sequence in the batch, or use padding=’max_length’ to pad to a max length. In this case, you can give a specific length with max_length (e.g. max_length=45) or leave max_length to None to pad to the maximal input size of the model (e.g. 512 for Bert).”

- So the call would look like this:

# Encode a batch of sentences with dynamic padding.

encoded_dict = tokenizer.batch_encode_plus(

train_text[i:i+batch_size], # Batch of sentences to encode.

add_special_tokens = True, # Add '[CLS]' and '[SEP]'

padding = 'longest', # Pad to longest in batch.

truncation = True, # Truncate sentences to `max_length`.

max_length = 400,

return_attention_mask = True, # Construct attn. masks.

return_tensors = 'pt', # Return pytorch tensors.

)

-

However, if you do this, you need wait to actually encode your text until the random training samples for the batch have been selected! i.e., you can’t pre-tokenize all of your sentences the way we have been.

-

The “correct” approach would be to implement a custom DataLoader class which:

- Stores the original training sample strings, sorted by string length.

- Selects a contiguous batch of samples starting at a random point in the list.

- Calls

batch_encode_plusto encode the samples with dynamic padding, then returns the training batch.

Impact of [PAD] tokens on accuracy

-

The difference in accuracy (0.93 for fixed-padding and 0.935 for smart batching) is interesting. It makes me curious to look at the attention mask implementation more–perhaps the

[PAD]tokens are still having some small influence on the results. -

Maybe the Attention scores are calculated for all tokens, including the

[PAD]tokens, and then the scores are multiplied against the mask, to zero out the scores for the[PAD]tokens? Because the SoftMax makes all of the attention scores sum to 1.0, that would mean the presence of[PAD]tokens would cause the scores for the real words to be lower…

Out of memory (OOM) errors

- OOM errors can happen due to bugs in your code or using the wrong version of PyTorch/CUDA. Some OOMs come from sub-optimal code in do_sample, such as storing extra tensors (e.g., storing the entire set of logits rather than just the sampled token index) or failing to wrap your sampling code with

torch.inference_mode(). -

Another way to save memory in

do_sample()is to avoid saving the full outputs object from the model. That is, instead of:output = model(input_ids) logits = output.logits[:, -1, :]- maybe just do

logits = model(input_ids).logits[:, -1, :]- so you aren’t saving the full model outputs variable (including the full logits output tensor, which can add up to a few hundred MB of memory).

Further Reading

References

- Weights and Biases: Train HuggingFace Models Twice As Fast

- Smart Batching Tutorial - Speed Up BERT Training

Citation

If you found our work useful, please cite it as:

@article{Chadha2020DistilledFineTuneAndEvalBERT,

title = {Fine-Tuning and Evaluating BERT},

author = {Chadha, Aman},

journal = {Distilled AI},

year = {2020},

note = {\url{https://aman.ai}}

}