Primers • Dropout

- Introduction

- Problem With Overfitting

- Randomly Drop Nodes

- How to Dropout

- Examples of using Dropout

- Tips for Using Dropout Regularization

- Further Reading

- Dropout vs. Inverted Dropout

- Key takeaways

- Citation

Introduction

-

Deep learning neural networks are likely to quickly overfit a training dataset with few examples.

-

Ensembles of neural networks with different model configurations are known to reduce overfitting, but require the additional computational expense of training and maintaining multiple models.

-

A single model can be used to simulate having a large number of different network architectures by randomly dropping out nodes during training. This is called dropout and offers a very computationally cheap and remarkably effective regularization method to reduce overfitting and improve generalization error in deep neural networks of all kinds.

-

In this post, you will discover the use of dropout regularization for reducing overfitting and improving the generalization of deep neural networks.

Problem With Overfitting

-

Large neural nets trained on relatively small datasets can overfit the training data.

-

This has the effect of the model learning the statistical noise in the training data, which results in poor performance when the model is evaluated on new data, e.g. a test dataset. Generalization error increases due to overfitting.

-

One approach to reduce overfitting is to fit all possible different neural networks on the same dataset and to average the predictions from each model. This is not feasible in practice, and can be approximated using a small collection of different models, called an ensemble.

With unlimited computation, the best way to “regularize” a fixed-sized model is to average the predictions of all possible settings of the parameters, weighting each setting by its posterior probability given the training data. — Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014.

- A problem even with the ensemble approximation is that it requires multiple models to be fit and stored, which can be a challenge if the models are large, requiring days or weeks to train and tune.

Randomly Drop Nodes

-

Dropout, proposed in Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting by Srivastava et al. (2014), is a regularization method that approximates training a large number of neural networks with different architectures in parallel.

-

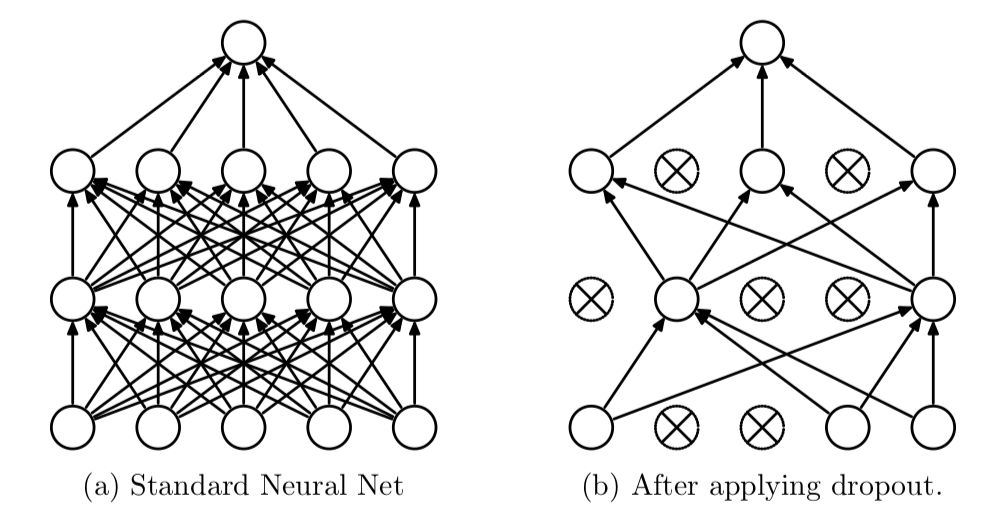

During training, some number of layer outputs are randomly ignored or “dropped out.” This has the effect of making the layer look-like and be treated-like a layer with a different number of nodes and connectivity to the prior layer. In effect, each update to a layer during training is performed with a different “view” of the configured layer (as shown below, diagram taken from Srivastava et al., 2014).

By dropping a unit out, we mean temporarily removing it from the network, along with all its incoming and outgoing connections. — Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014.

-

Dropout has the effect of making the training process noisy, forcing nodes within a layer to probabilistically take on more or less responsibility for the inputs.

-

This conceptualization suggests that perhaps dropout breaks-up situations where network layers co-adapt to correct mistakes from prior layers, in turn making the model more robust.

… units may change in a way that they fix up the mistakes of the other units. This may lead to complex co-adaptations. This in turn leads to overfitting because these co-adaptations do not generalize to unseen data. […] — Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014.

- Dropout simulates a sparse activation from a given layer, which interestingly, in turn, encourages the network to actually learn a sparse representation as a side-effect. As such, it may be used as an alternative to activity regularization for encouraging sparse representations in autoencoder models.

We found that as a side-effect of doing dropout, the activations of the hidden units become sparse, even when no sparsity inducing regularizers are present. — Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014.

- Because the outputs of a layer under dropout are randomly subsampled, it has the effect of reducing the capacity or thinning the network during training. As such, a wider network, e.g. more nodes, may be required when using dropout.

How to Dropout

-

Dropout is implemented per-layer in a neural network.

-

It can be used with most types of layers, such as dense fully connected layers, convolutional layers, and recurrent layers such as the long short-term memory network layer.

-

Dropout may be implemented on any or all hidden layers in the network as well as the visible or input layer. It is not used on the output layer.

The term “dropout” refers to dropping out units (hidden and visible) in a neural network. — Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014.

-

A new hyperparameter is introduced that specifies the probability at which outputs of the layer are dropped out, or inversely, the probability at which outputs of the layer are retained. The interpretation is an implementation detail that can differ from paper to code library.

-

A common value is a probability of 0.5 for retaining the output of each node in a hidden layer and a value close to 1.0, such as 0.8, for retaining inputs from the visible layer.

In the simplest case, each unit is retained with a fixed probability p independent of other units, where p can be chosen using a validation set or can simply be set at 0.5, which seems to be close to optimal for a wide range of networks and tasks. For the input units, however, the optimal probability of retention is usually closer to 1 than to 0.5. — Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014. - Dropout is not used after training when making a prediction with the fit network.

- The weights of the network will be larger than normal because of dropout. Therefore, before finalizing the network, the weights are first scaled by the chosen dropout rate. The network can then be used as per normal to make predictions.

If a unit is retained with probability p during training, the outgoing weights of that unit are multiplied by \(p\) at test time. — Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014.

- The rescaling of the weights can be performed at training time instead, after each weight update at the end of the mini-batch. This is sometimes called “inverse dropout” and does not require any modification of weights during training. Both the Keras and PyTorch deep learning libraries implement dropout in this way.

At test time, we scale down the output by the dropout rate. […] Note that this process can be implemented by doing both operations at training time and leaving the output unchanged at test time, which is often the way it’s implemented in practice. — Page 109, Deep Learning With Python, 2017.

- Dropout works well in practice, perhaps replacing the need for weight regularization (e.g. weight decay) and activity regularization (e.g. representation sparsity).

… dropout is more effective than other standard computationally inexpensive regularizers, such as weight decay, filter norm constraints and sparse activity regularization. Dropout may also be combined with other forms of regularization to yield a further improvement. — Page 265, Deep Learning, 2016.

Examples of using Dropout

-

This section summarizes some examples where dropout was used in recent research papers to provide a suggestion for how and where it may be used.

-

Geoffrey Hinton, et al. in their 2012 paper that first introduced dropout titled “Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors” applied used the method with a range of different neural networks on different problem types achieving improved results, including handwritten digit recognition (MNIST), photo classification (CIFAR-10), and speech recognition (TIMIT).

… we use the same dropout rates – 50% dropout for all hidden units and 20% dropout for visible units.

- Nitish Srivastava, et al. in their 2014 journal paper introducing dropout titled “Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting” used dropout on a wide range of computer vision, speech recognition, and text classification tasks and found that it consistently improved performance on each problem.

We trained dropout neural networks for classification problems on data sets in different domains. We found that dropout improved generalization performance on all data sets compared to neural networks that did not use dropout.

- On the computer vision problems, different dropout rates were used down through the layers of the network in conjunction with a max-norm weight constraint.

Dropout was applied to all the layers of the network with the probability of retaining the unit being \(p = (0.9, 0.75, 0.75, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5)\) for the different layers of the network (going from input to convolutional layers to fully connected layers). In addition, the max-norm constraint with \(c = 4\) was used for all the weights. […ereg]

- A simpler configuration was used for the text classification task.

We used probability of retention p = 0.8 in the input layers and 0.5 in the hidden layers. Max-norm constraint with \(c = 4\) was used in all the layers.

- Alex Krizhevsky, et al. in their famous 2012 paper titled “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks” achieved (at the time) state-of-the-art results for photo classification on the ImageNet dataset with deep convolutional neural networks and dropout regularization.

We use dropout in the first two fully-connected layers [of the model]. Without dropout, our network exhibits substantial overfitting. Dropout roughly doubles the number of iterations required to converge.

- George Dahl, et al. in their 2013 paper titled “Improving deep neural networks for LVCSR using rectified linear units and dropout” used a deep neural network with rectified linear activation functions and dropout to achieve (at the time) state-of-the-art results on a standard speech recognition task. They used a bayesian optimization procedure to configure the choice of activation function and the amount of dropout.

… the Bayesian optimization procedure learned that dropout wasn’t helpful for sigmoid nets of the sizes we trained. In general, ReLUs and dropout seem to work quite well together.

Tips for Using Dropout Regularization

- This section provides some tips for using dropout regularization with your neural network.

Use With All Network Types

-

Dropout regularization is a generic approach.

-

It can be used with most, perhaps all, types of neural network models, not least the most common network types of Multilayer Perceptrons, Convolutional Neural Networks, and Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Networks.

-

In the case of LSTMs, it may be desirable to use different dropout rates for the input and recurrent connections.

Dropout Rate

-

The default interpretation of the dropout hyperparameter is the probability of training a given node in a layer, where 1.0 means no dropout, and 0.0 means no outputs from the layer.

-

A good value for dropout in a hidden layer is between 0.5 and 0.8. Input layers use a larger dropout rate, such as of 0.8.

Use a Larger Network

-

It is common for larger networks (more layers or more nodes) to more easily overfit the training data.

-

When using dropout regularization, it is possible to use larger networks with less risk of overfitting. In fact, a large network (more nodes per layer) may be required as dropout will probabilistically reduce the capacity of the network.

-

A good rule of thumb is to divide the number of nodes in the layer before dropout by the proposed dropout rate and use that as the number of nodes in the new network that uses dropout. For example, a network with 100 nodes and a proposed dropout rate of 0.5 will require 200 nodes (100 / 0.5) when using dropout.

If \(n\) is the number of hidden units in any layer and \(p\) is the probability of retaining a unit […] a good dropout net should have at least \(n/p\) units

— Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014.

Grid Search Dropout Rate

-

Rather than guess at a suitable dropout rate for your network, test different rates systematically.

-

For example, test values between 1.0 and 0.1 in increments of 0.1.

-

This will both help you discover what works best for your specific model and dataset, as well as how sensitive the model is to the dropout rate. A more sensitive model may be unstable and could benefit from an increase in size.

Use a Weight Constraint

-

Network weights will increase in size in response to the probabilistic removal of layer activations.

-

Large weight size can be a sign of an unstable network.

-

To counter this effect a weight constraint can be imposed to force the norm (magnitude) of all weights in a layer to be below a specified value. For example, the maximum norm constraint is recommended with a value between 3-4.

[…] we can use max-norm regularization. This constrains the norm of the vector of incoming weights at each hidden unit to be bound by a constant \(c\). Typical values of \(c\) range from 3 to 4. — Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014.

This does introduce an additional hyperparameter that may require tuning for the model.

Use With Smaller Datasets

-

Like other regularization methods, dropout is more effective on those problems where there is a limited amount of training data and the model is likely to overfit the training data.

-

Problems where there is a large amount of training data may see less benefit from using dropout.

For very large datasets, regularization confers little reduction in generalization error. In these cases, the computational cost of using dropout and larger models may outweigh the benefit of regularization. — Page 265, Deep Learning, 2016.

Further Reading

- This section provides more resources on the topic if you are looking to go deeper.

Books

- Section 7.12 Dropout, Deep Learning, 2016

- Section 4.4.3 Adding dropout, Deep Learning With Python, 2017

Papers

- Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors, 2012

- Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting, 2014

- Improving deep neural networks for LVCSR using rectified linear units and dropout, 2013

- Dropout Training as Adaptive Regularization, 2013

Articles

- Dropout (neural networks), Wikipedia

- Regularization, CS231n Convolutional Neural Networks for Visual Recognition

- How was ‘Dropout’ conceived? Was there an ‘aha’ moment?

Dropout vs. Inverted Dropout

- Dropout and inverted dropout are techniques used in neural networks to prevent overfitting, but the main difference between them lies in how dropout is implemented. Here’s a breakdown:

- Dropout:

- During training, randomly set a fraction p of the input units to 0 at each update. For example, if we use a dropout rate of 0.5, it means that half of the input units will be set to zero during the forward pass.

- During testing, the network uses all units but multiplies their outputs by \((1-p)\) to account for the expected output given that only a fraction \((1-p)\) of the units were active on average during training.

- Inverted Dropout:

- It’s essentially a variant of dropout that simplifies the process especially at test time.

- During training, we again randomly set a fraction \(p\) of the input units to 0, but then scale the remaining units by \(1/(1-p)\). This is to ensure that the expected sum remains the same. Using our previous example with a dropout rate of 0.5, the active units would be scaled by a factor of 2 (because \(\frac{1}{1-0.5} = 2\)).

- During testing, no adjustments are needed, as the scaling has already been accounted for during training. This means we can use the trained network directly without needing to multiply by \((1-p)\) as in the regular dropout.

- Advantages of Inverted Dropout:

- The primary advantage of using inverted dropout is that there’s no need for any modification or scaling during the testing phase. Once the model is trained, you can directly use it for inference, making the process more streamlined and efficient.

- Regardless of the variant you use, the central idea remains the same: dropout helps in introducing randomness in the training process, ensuring that the model doesn’t rely too much on any single neuron and thereby reducing the chances of overfitting.

Key takeaways

-

In this post, you discovered the use of dropout regularization for reducing overfitting and improving the generalization of deep neural networks.

-

Specifically, you learned:

- Large weights in a neural network are a sign of a more complex network that has overfit the training data.

- Probabilistically dropping out nodes in the network is a simple and effective regularization method.

- A large network with more training and the use of a weight constraint are suggested when using dropout.

Citation

If you found our work useful, please cite it as:

@article{Chadha2020DistilledDropout,

title = {Dropout},

author = {Chadha, Aman},

journal = {Distilled AI},

year = {2020},

note = {\url{https://aman.ai}}

}