Primers • Diffusion Models

- Background

- Overview

- Introduction

- Transformers vs. Diffusion Models

- Advantages

- Definitions

- Diffusion Models: The Theory

- Diffusion Models as Latent-Variable Generative Models

- Markovian Structure and Tractability

- Fixed Forward Process and Learned Reverse Process

- Likelihood-Based Training via Variational Inference

- Noise Prediction Parameterization

- Connection to Continuous-Time/Score-Based Models

- Discrete Data and Final Decoding

- Takeaways

- Diffusion Models: A Deep Dive

- Taxonomy of Diffusion Models

- Discrete-Time Diffusion Models

- Continuous-Time Diffusion Models (Representation-Agnostic)

- Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE)-Based Diffusion Models

- Score-Based Generative Modeling (SGMs)

- Reverse-Time SDE and Sampling

- Sampling via Langevin Dynamics (Discrete Approximation)

- Probability Flow ODE (Deterministic Sampling)

- Flow Matching Models (Deterministic Continuous-Time Generative Models)

- Comparative Analysis

- Training

- Model Choices

- Network Architecture: U-Net and Diffusion Transformer (DiT)

- Conditional Diffusion Models

- Conditioning Mechanisms

- Text Conditioning in Diffusion Models

- Visual Conditioning in Diffusion Models

- Multi-Modal Conditioning (Text + Image(s) + Other Modalities)

- Unified Multi-Modal Conditioning Representation

- Cross-Attention with Multiple Modalities

- Modality-Specific Injection (ControlNet-Style Conditioning)

- Spatially Aligned vs. Token-Based Modalities

- Training Objective with Multi-Modal Conditioning

- Classifier-Free Guidance with Multi-Modal Inputs

- Practical Capabilities Enabled

- Classifier-Free Guidance

- Video Diffusion Models

- Evaluation Metrics

- Prompting Guidance

- Integrating Diffusion Models with an Large Language Model (LLM) Backbone

- Overall Architecture

- Representations Exchanged Between the LLM and Diffusion

- Conditioning Injection into the Diffusion Model

- Training Strategies

- Base Objective (Shared Across Strategies)

- Strategy A: Freeze Diffusion, Train Projection Layers Only

- Strategy B: Train Projection Layers + Top LLM Layers

- Strategy C: Partial Joint Fine-Tuning with Diffusion

- Classifier-Free Guidance Training

- Auxiliary Losses (Optional)

- Curriculum and Scheduling

- Stability Techniques

- Encouraging the LLM to “Think in Images”

- Latent-Space Supervision

- Inference and Iterative Refinement

- Diffusion Models in PyTorch

- HuggingFace Diffusers

- Implementations

- Gallery

- FAQs

- At a high level, how do diffusion models work? What are some other models that are useful for image generation, and how do they compare to diffusion models?

- What is the difference between DDPM and DDIMs models?

- In diffusion models, there is a forward diffusion process and a reverse diffusion/denoising process. When do you use which during training and inference?

- What are the loss functions used in Diffusion Models?

- If diffusion models are trained by maximizing a variational lower bound (ELBO) on the data log-likelihood, how does this probabilistic objective reconcile with the simple regression-style MSE loss used for noise prediction in practice?

- What is the Denoising Score Matching Loss in Diffusion models? Explain with an equation and intuition.

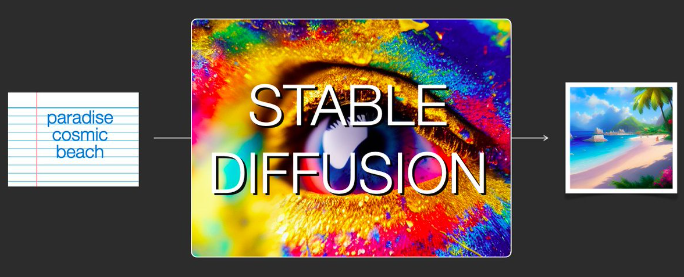

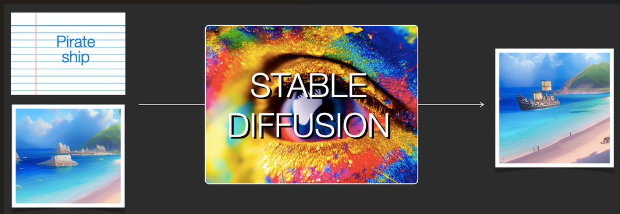

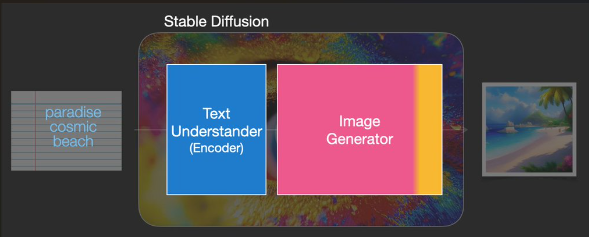

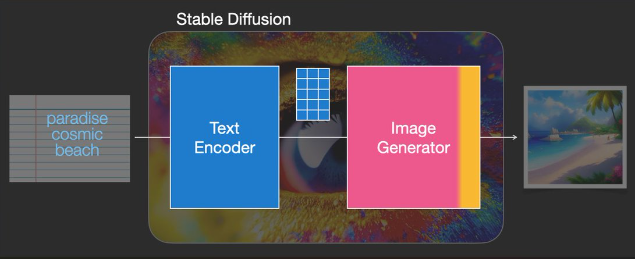

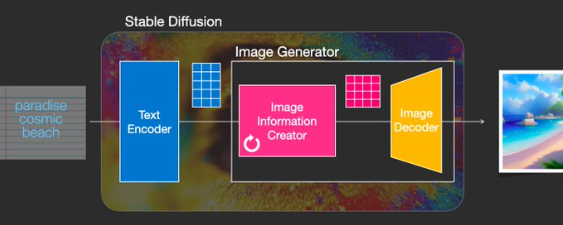

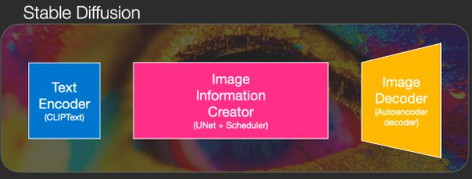

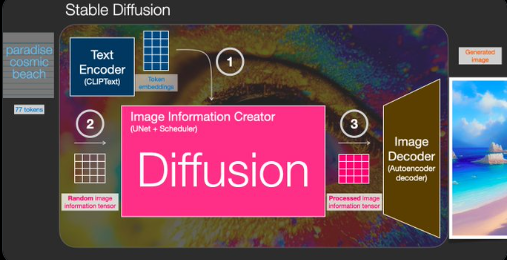

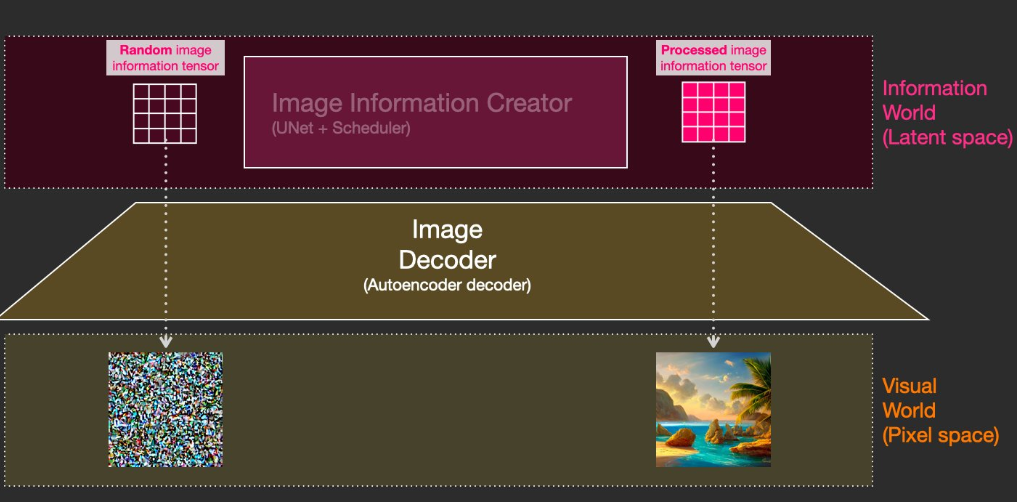

- What does the “stable” in stable diffusion refer to?

- How do you condition a diffusion model to the textual input prompt?

- In the context of diffusion models, what role does cross attention play? How are the \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\) abstractions modeled for diffusion models?

- How is randomness in the outputs induced in a diffusion model?

- How does the noise schedule work in diffusion models? What are some standard noise schedules?

- Choosing a Noise Schedule

- Relevant Papers

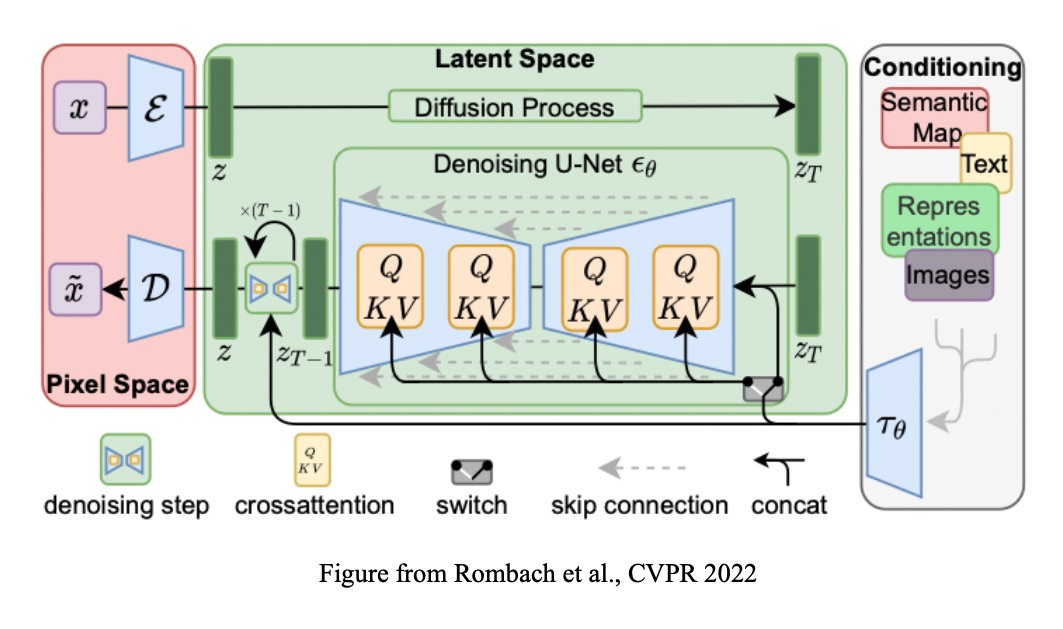

- High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models

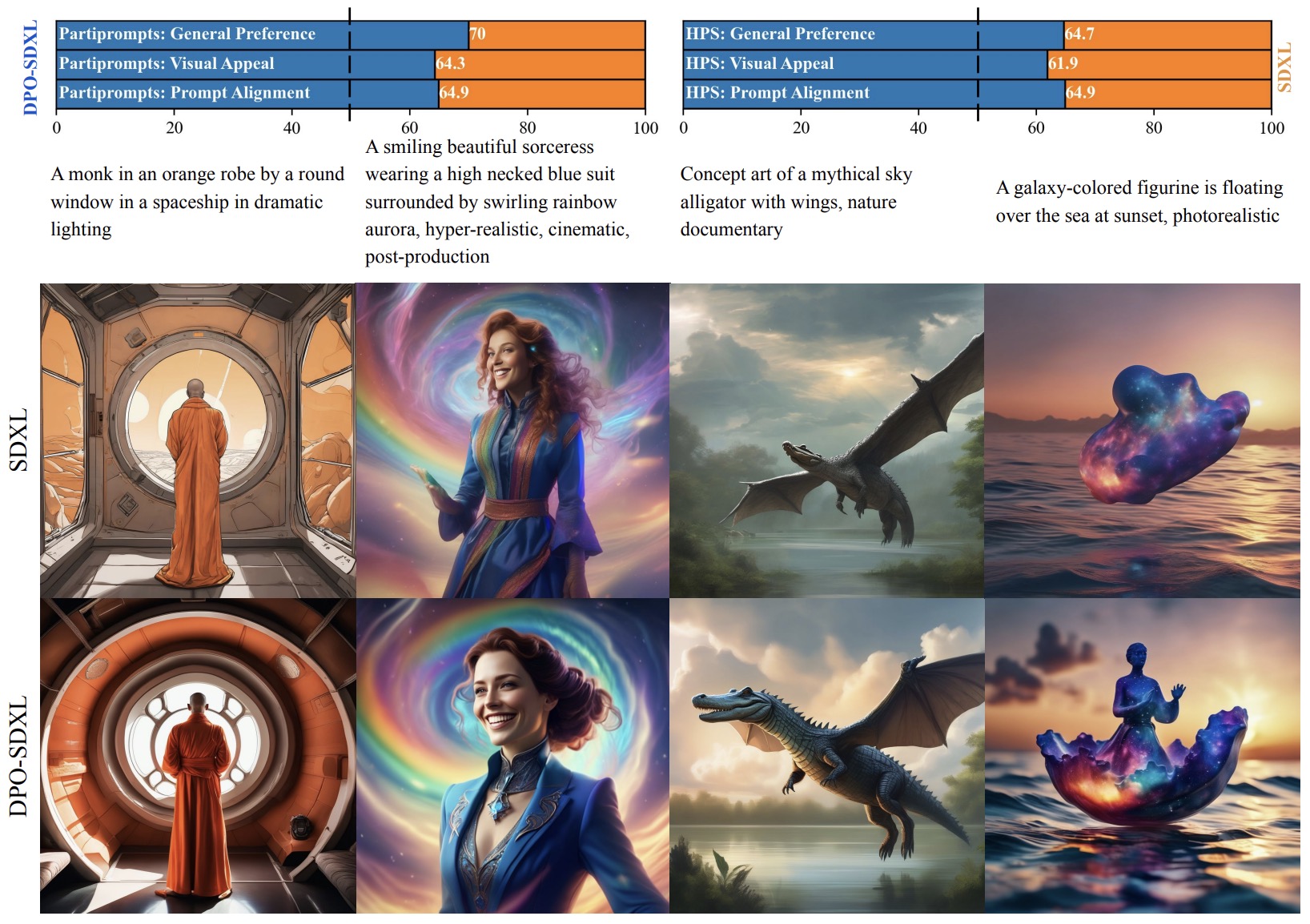

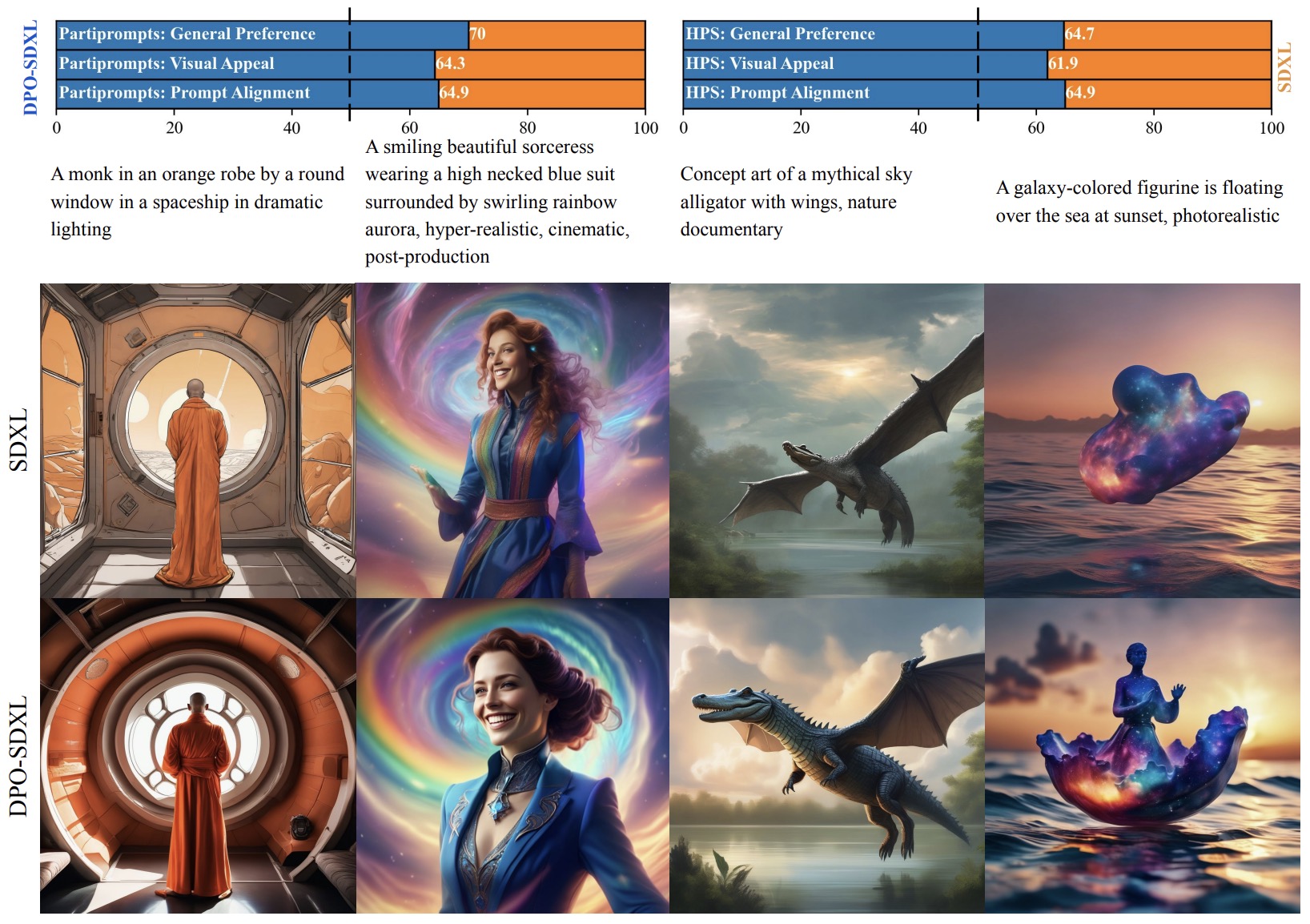

- Diffusion Model Alignment Using Direct Preference Optimization

- Scalable Diffusion Models with Transformers

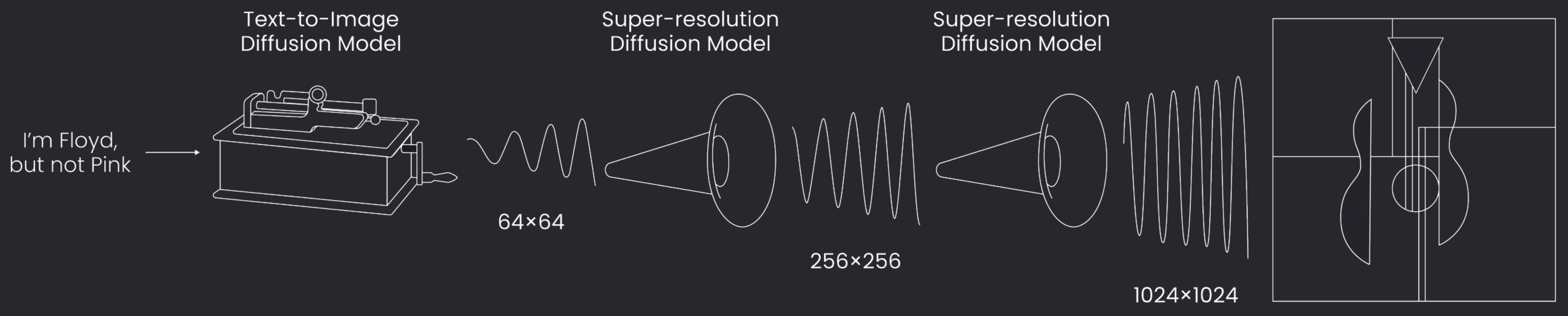

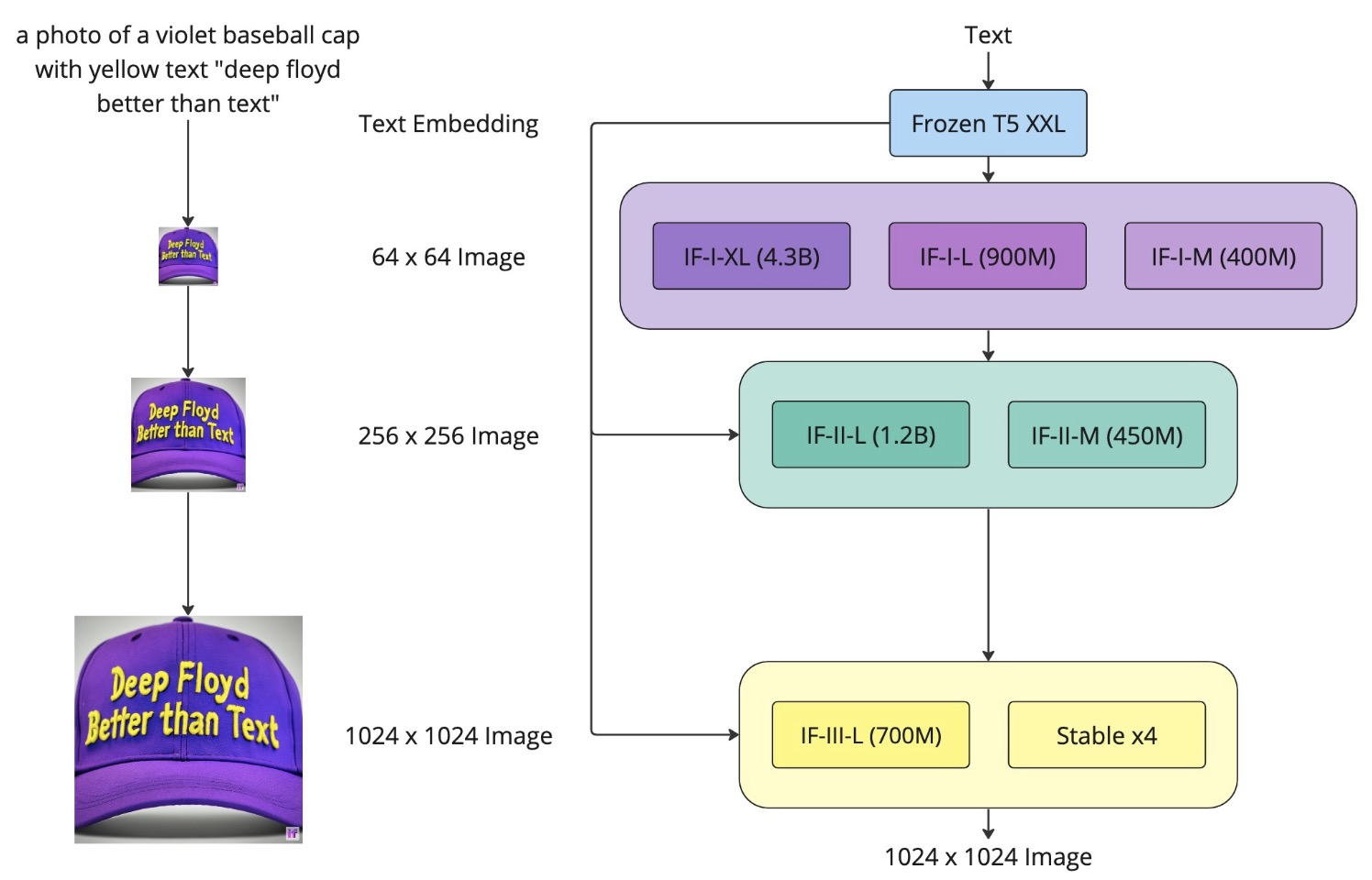

- DeepFloyd IF

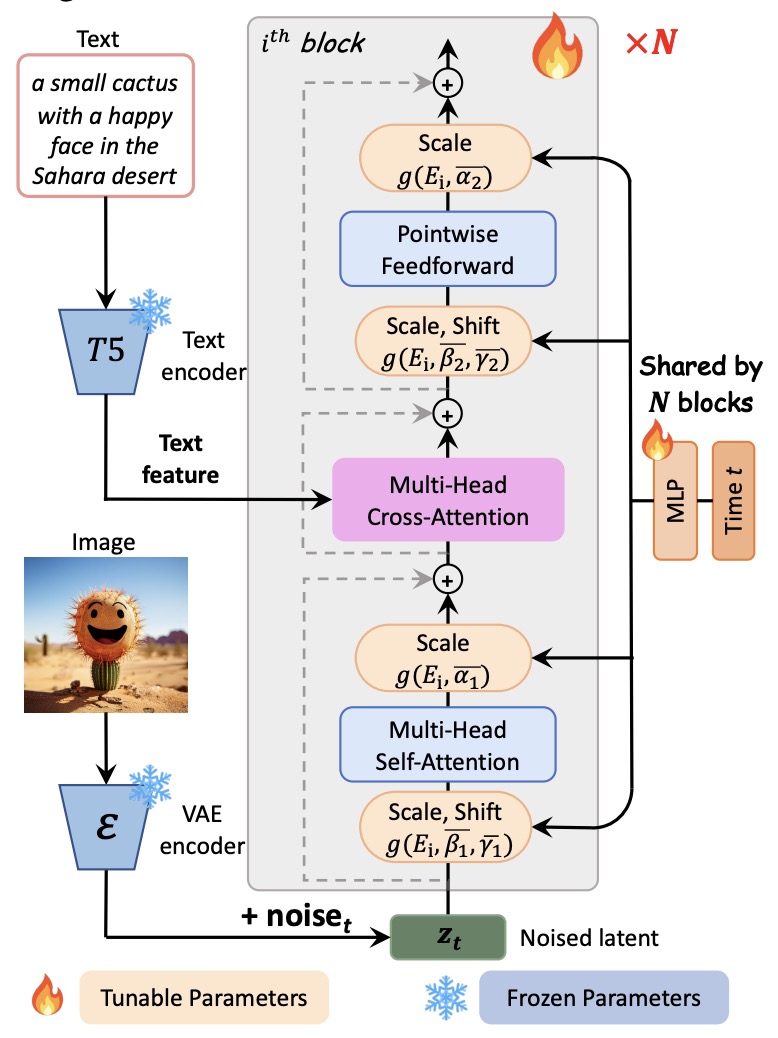

- PIXART-\(\alpha\): Fast Training of Diffusion Transformer for Photorealistic Text-to-Image Synthesis

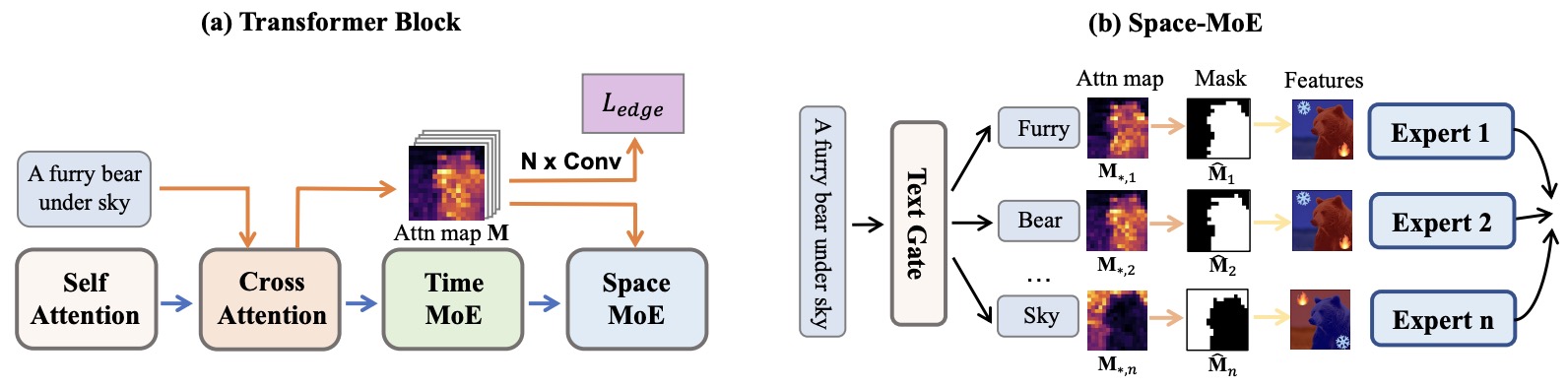

- RAPHAEL: Text-to-Image Generation via Large Mixture of Diffusion Paths

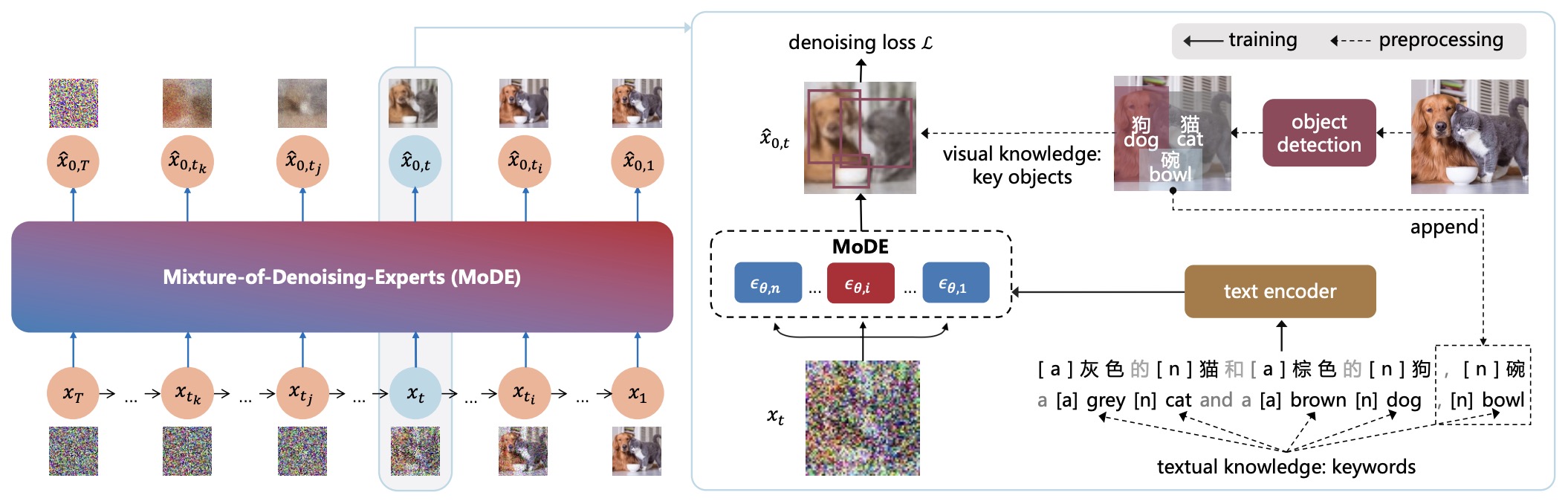

- ERNIE-ViLG 2.0: Improving Text-to-Image Diffusion Model with Knowledge-Enhanced Mixture-of-Denoising-Experts

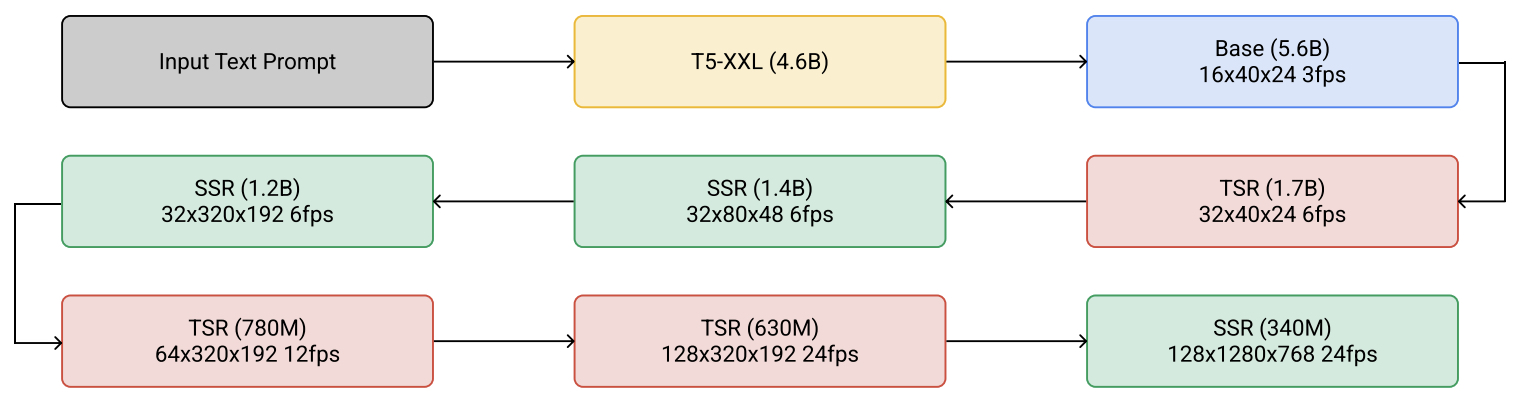

- Imagen Video: High Definition Video Generation with Diffusion Models

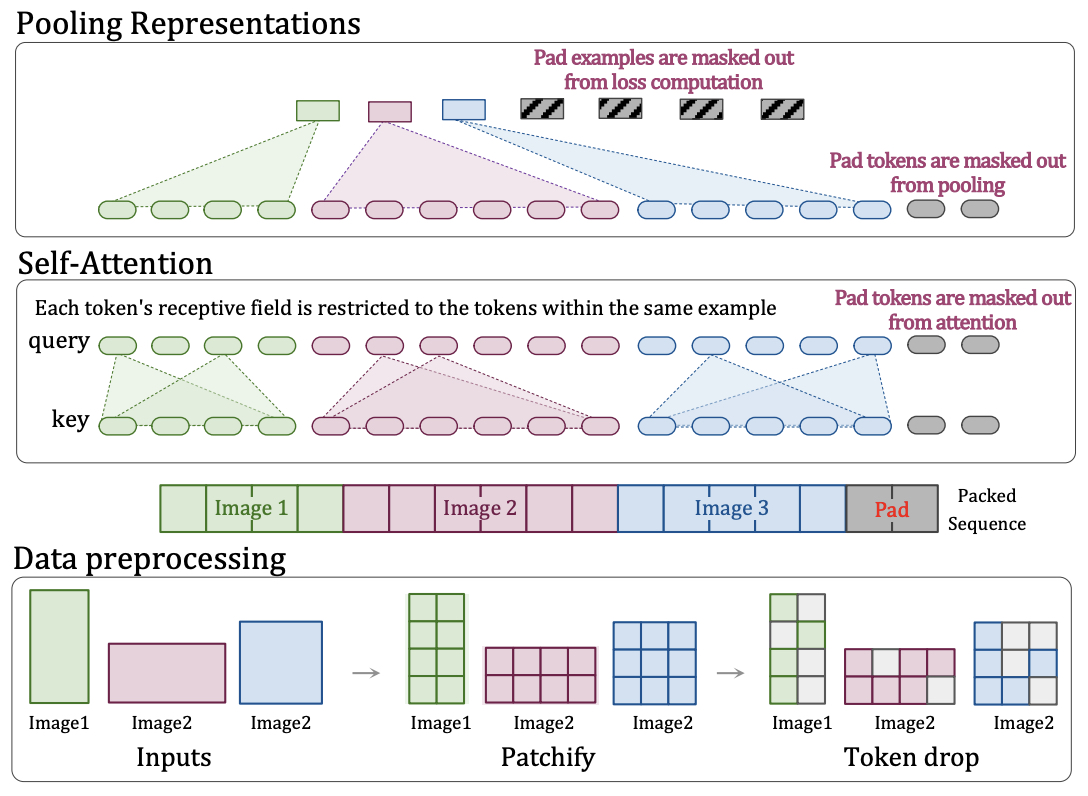

- Patch n’ Pack: NaViT, a Vision Transformer for any Aspect Ratio and Resolution

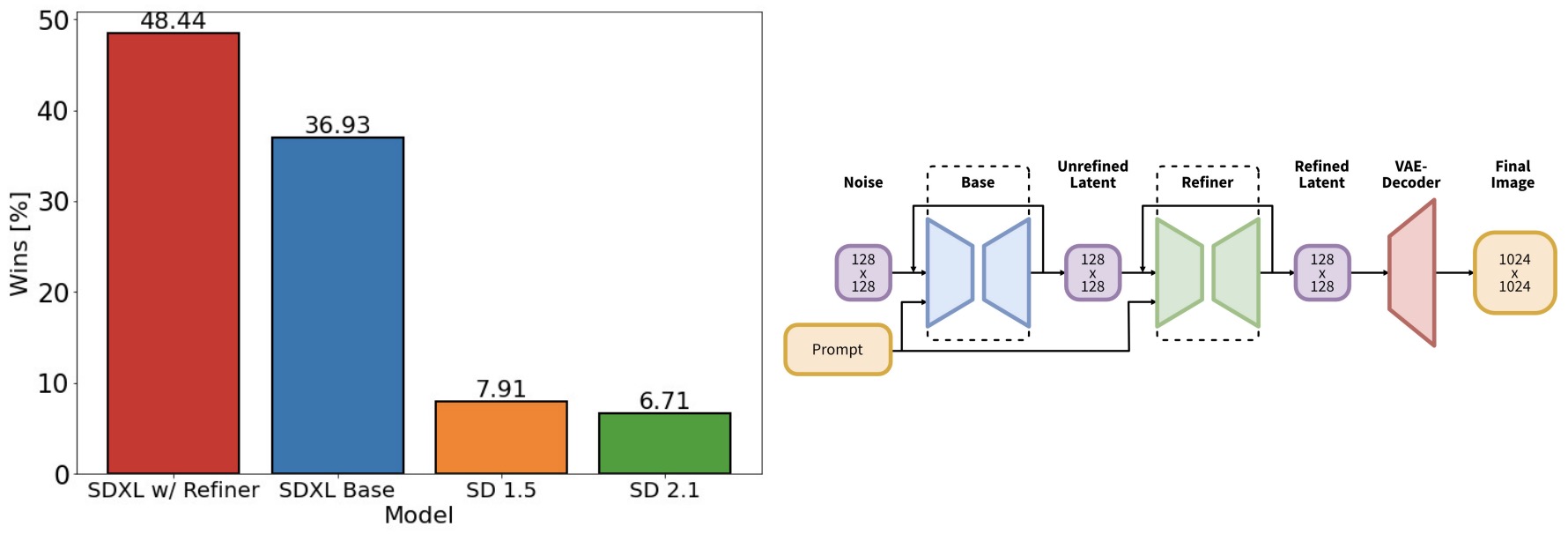

- SDXL: Improving Latent Diffusion Models for High-Resolution Image Synthesis

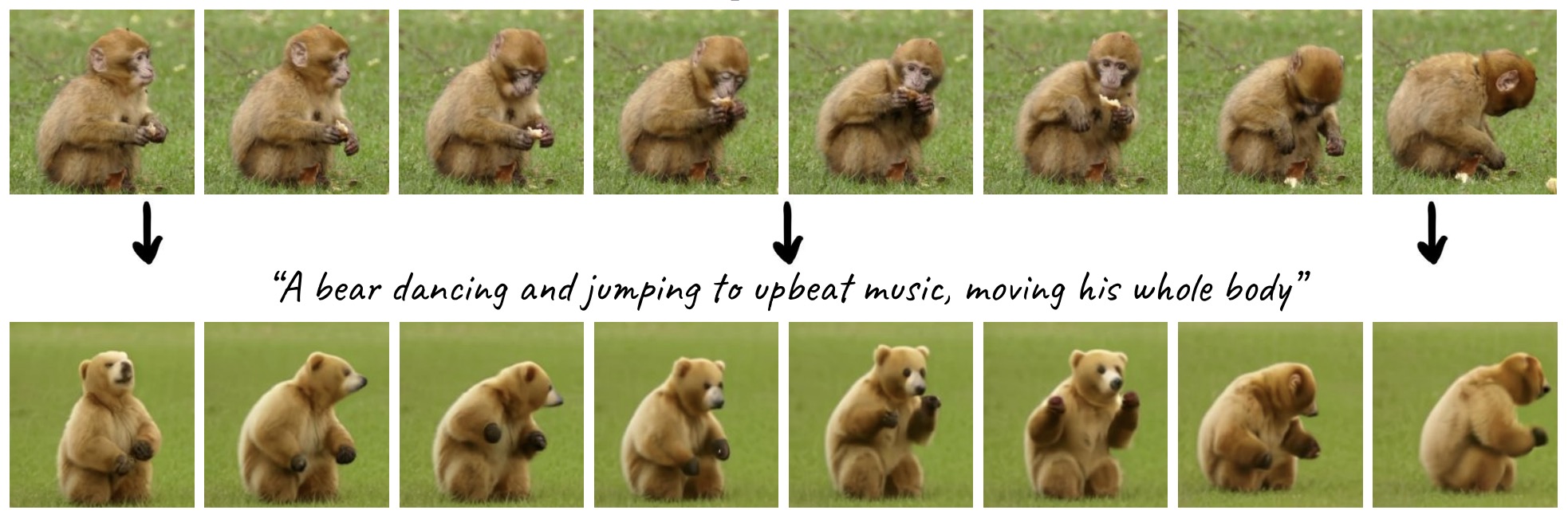

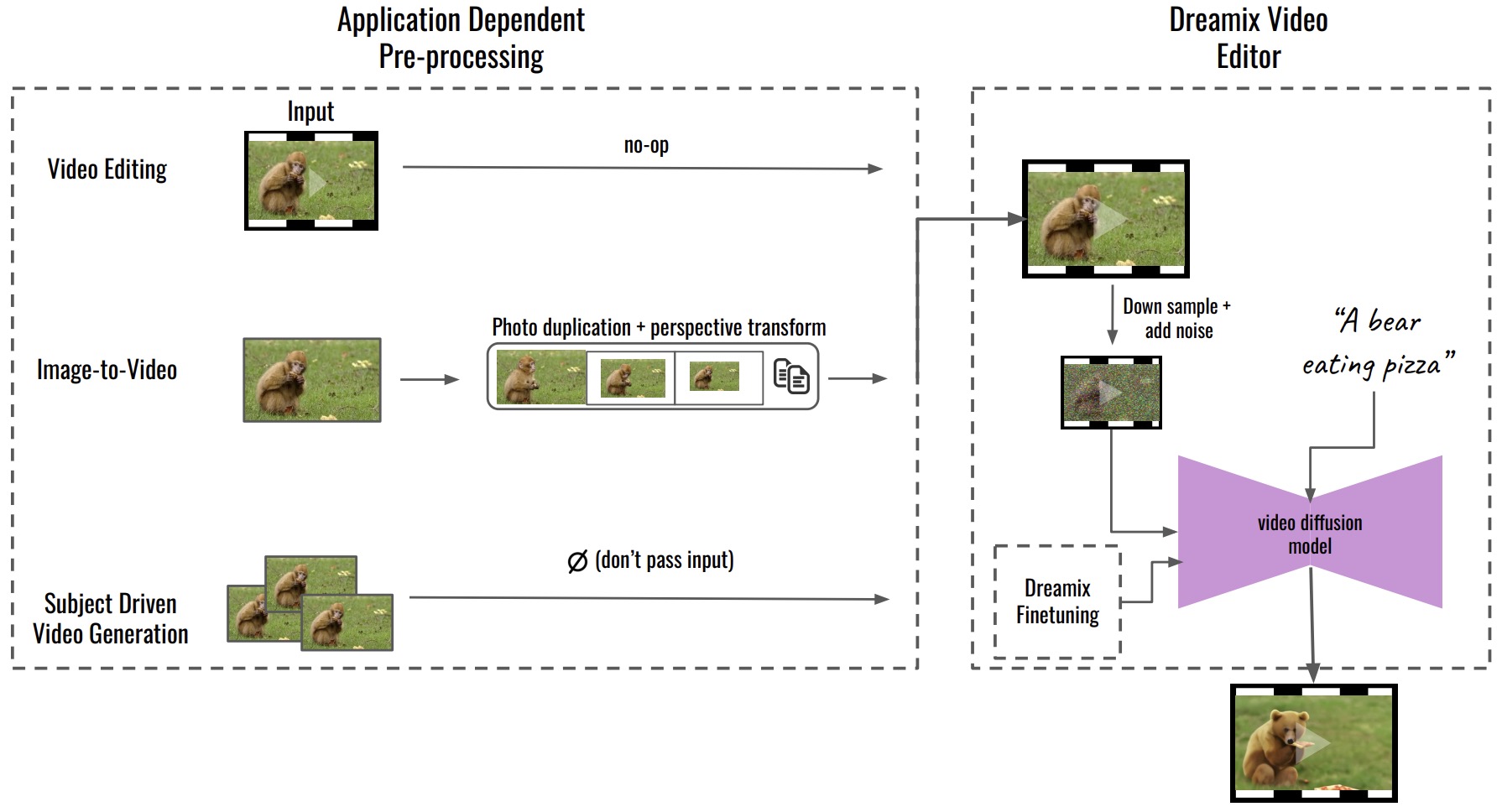

- Dreamix: Video Diffusion Models are General Video Editors

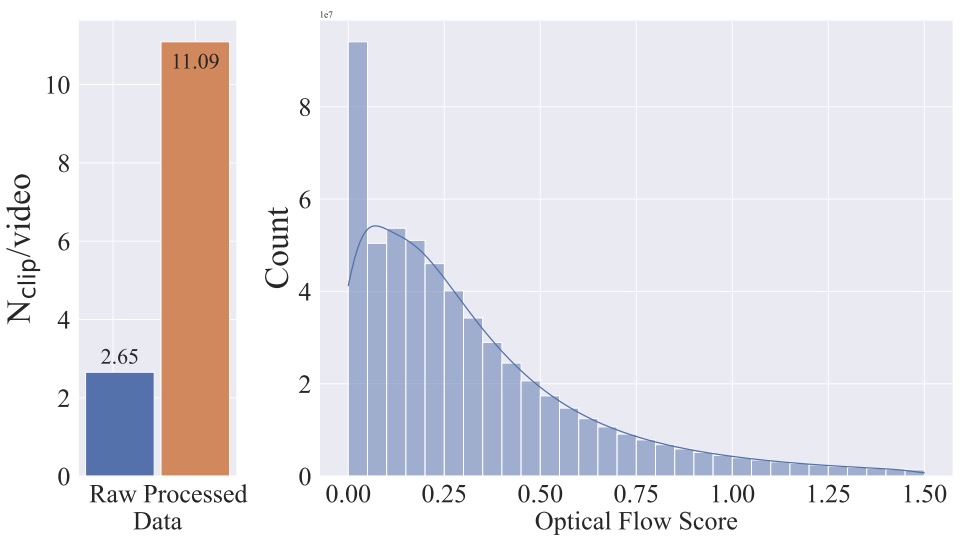

- Stable Video Diffusion: Scaling Latent Video Diffusion Models to Large Datasets

- Fine-tuning Diffusion Models

- Diffusion Model Alignment

- Further Reading

- The Illustrated Stable Diffusion

- Understanding Diffusion Models: A Unified Perspective

- The Annotated Diffusion Model

- Lilian Weng: What are Diffusion Models?

- Stable Diffusion - What, Why, How?

- How does Stable Diffusion work? – Latent Diffusion Models Explained

- Diffusion Explainer

- Jupyter notebook on the theoretical and implementation aspects of Score-based Generative Models (SGMs)

- References

- Citation

Background

-

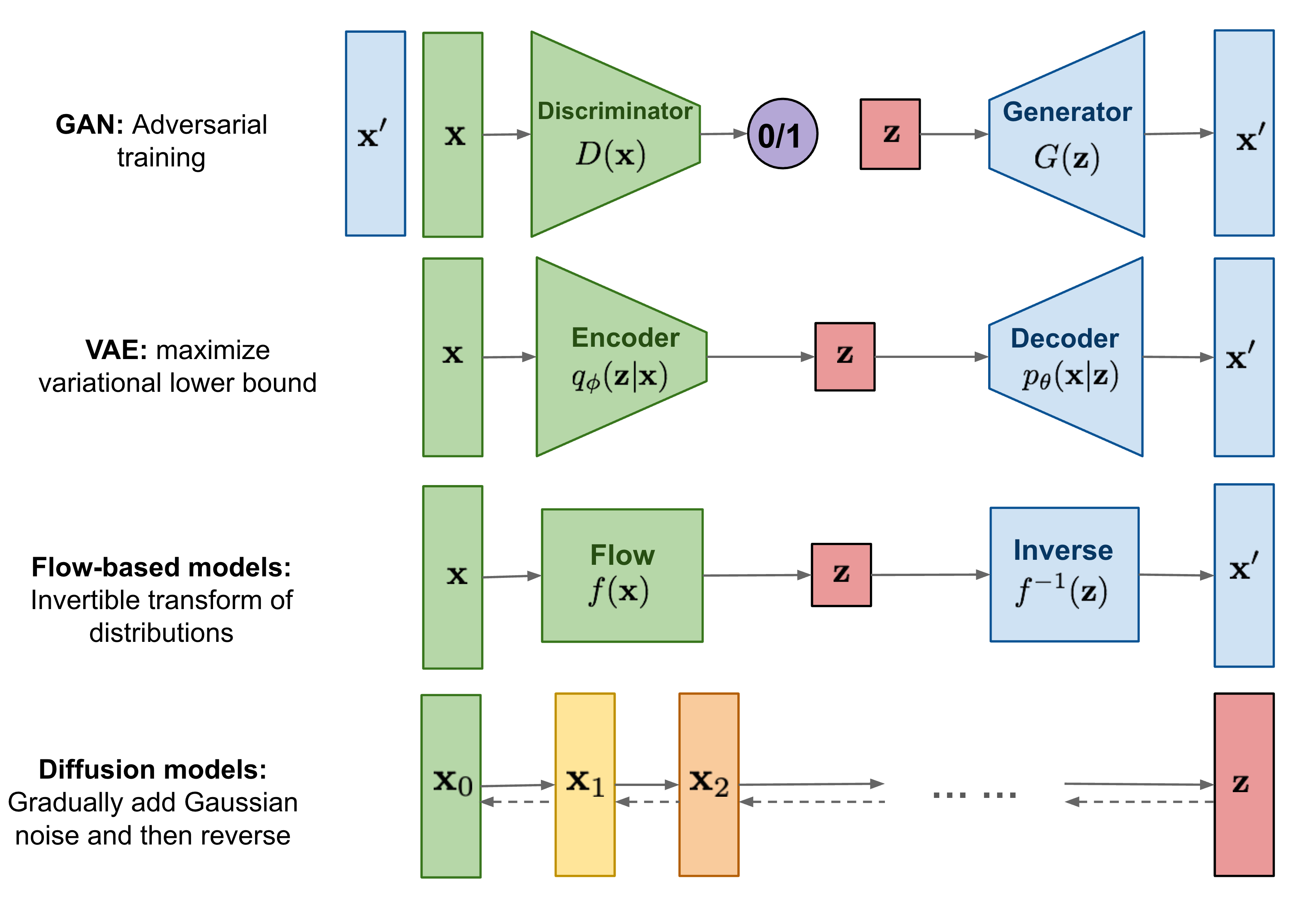

Generative modeling is a central problem in machine learning, concerned with learning a probability distribution \(p(x)\) from which new, realistic data samples can be drawn. Over the past decade, three families of generative models have dominated the literature: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and normalizing flow–based models. Each of these paradigms offers distinct advantages while also exhibiting fundamental limitations.

-

GANs, introduced in Generative Adversarial Nets by Goodfellow et al. (2014), rely on an adversarial training framework in which a generator and discriminator compete in a minimax game. While GANs are capable of producing highly sharp and realistic samples, their training dynamics are notoriously unstable and sensitive to hyperparameters, often suffering from mode collapse and lack of diversity (cf. On the Convergence and Stability of GANs by Mescheder et al. (2018)). Moreover, GANs do not provide an explicit likelihood, i.e., they do not assign a clear probability to how likely a given data sample is under the model. This makes it difficult to objectively compare different models or measure how well a model has learned the data distribution. As a result, GANs are less suitable for applications that require reliable uncertainty estimates, principled evaluation metrics, or probabilistic decision-making.

-

VAEs, introduced in Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes by Kingma and Welling (2013), take a probabilistic approach by optimizing a variational lower bound on the data likelihood. VAEs are stable to train and provide an explicit generative density, but the reliance on surrogate objectives—such as Gaussian likelihood assumptions and KL regularization—often leads to overly smooth or blurry samples, particularly in image generation tasks.

-

Flow-based models, such as those introduced in Density Estimation using Real NVP by Dinh et al. (2016) and Glow: Generative Flow with Invertible 1×1 Convolutions by Kingma and Dhariwal (2018), address likelihood estimation directly via exact change-of-variables formulas. However, they require carefully designed invertible architectures with tractable Jacobians, which significantly constrains model design and increases implementation complexity.

Emergence of Diffusion Models

-

Diffusion models present a compelling alternative to these earlier generative paradigms. Inspired by ideas from non-equilibrium thermodynamics, diffusion models define a stochastic process that incrementally transforms data into noise through a fixed forward process, and then learn to reverse (i.e., invert) this process by denoising it step-by-step in order to generate samples. Unlike GANs, diffusion models do not rely on adversarial training, and unlike VAEs and flow-based models, they do not require restrictive architectural constraints or surrogate likelihood assumptions.

-

The foundational idea of diffusion-based generative modeling was introduced in Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics by Sohl-Dickstein et al. (2015). In this work, the authors proposed modeling data generation as the reversal of a gradual diffusion process, framing learning as approximating the reverse-time dynamics of a Markov chain that incrementally adds Gaussian noise.

-

Subsequent breakthroughs significantly improved the scalability and practicality of diffusion models. In Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution by Song and Ermon (2019), the authors introduced score-based generative modeling, showing that learning the gradient of the log-density of noisy data distributions suffices for generation. Shortly thereafter, Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020) reformulated diffusion models using a simplified and highly stable training objective based on noise prediction, dramatically improving sample quality and ease of implementation.

-

A concise visual overview situating diffusion models among other generative approaches is provided in the diagram below from Lilian Weng’s blog post “What are Diffusion Models?”:

Practical Adoption

-

Diffusion models are conceptually simple yet remarkably powerful. Their training procedure is stable, does not require adversarial objectives, and scales effectively with model size and data. As a result, diffusion models have rapidly become the dominant paradigm for high-fidelity generative modeling across multiple modalities, including images, audio, and video.

-

They form the core of several landmark systems for conditional and unconditional generation. Notable examples include GLIDE proposed in GLIDE: Towards Photorealistic Image Generation and Editing with Text-Guided Diffusion Models by Nichol et al. (2021), DALL·E 2 proposed in Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents by Ramesh et al. (2022), Latent Diffusion Models proposed in High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models by Rombach et al. (2022), Imagen proposed in Photorealistic Text-to-Image Diffusion Models with Deep Language Understanding by Saharia et al. (2022), and Stable Diffusion, developed by Stability AI.

-

These systems demonstrate that diffusion models are capable of matching or surpassing prior state-of-the-art generative approaches in both sample quality and controllability, while maintaining a principled probabilistic foundation.

-

Diffusion models are a relatively recent paradigm and remain an active area of research. Ongoing work explores faster and more efficient sampling methods, improved conditioning mechanisms, continuous-time formulations, and stronger theoretical guarantees. At the same time, core design choices such as optimal noise schedules, sampling algorithms, and architectural inductive biases are still being actively investigated. Their rapid adoption across academic research and industrial-scale systems highlights their growing importance as a unifying framework for modern generative modeling.

Overview

-

The rapid ascent of diffusion models represents one of the most significant developments in generative modeling over the past several years. Beginning as a theoretically motivated alternative to adversarial and variational approaches, diffusion models have evolved into a highly practical and dominant paradigm for high-fidelity data generation across a wide range of modalities.

-

Diffusion models are a class of likelihood-based generative models that construct complex data distributions through a sequence of simple stochastic transformations. Rather than generating samples in a single step, diffusion models define a multi-step process in which data are gradually corrupted by noise and then reconstructed by reversing this corruption. This incremental formulation enables diffusion models to decompose a challenging global modeling problem into a series of tractable local denoising tasks.

-

A sequence of influential papers in the early 2020s demonstrated that diffusion models can not only rival but often outperform GANs in terms of sample quality, training stability, and coverage of the data distribution; in particular, Diffusion Models Beat GANs on Image Synthesis by Dhariwal and Nichol (2021) reported Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores of 2.97 on ImageNet 128×128, 4.59 on ImageNet 256×256, and 7.72 on ImageNet 512×512, and showed that with classifier guidance diffusion models achieve FID as low as 3.94 at 256×256 and 3.85 at 512×512, matching or surpassing state-of-the-art GAN performance (specifically BigGAN-deep) while remaining more stable to train.

-

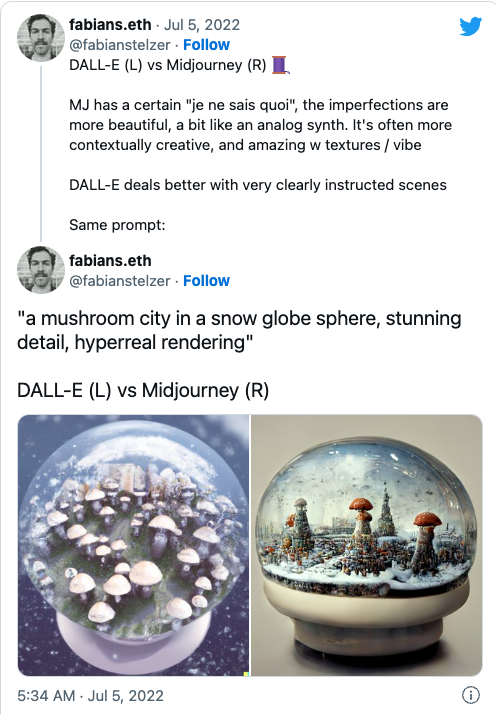

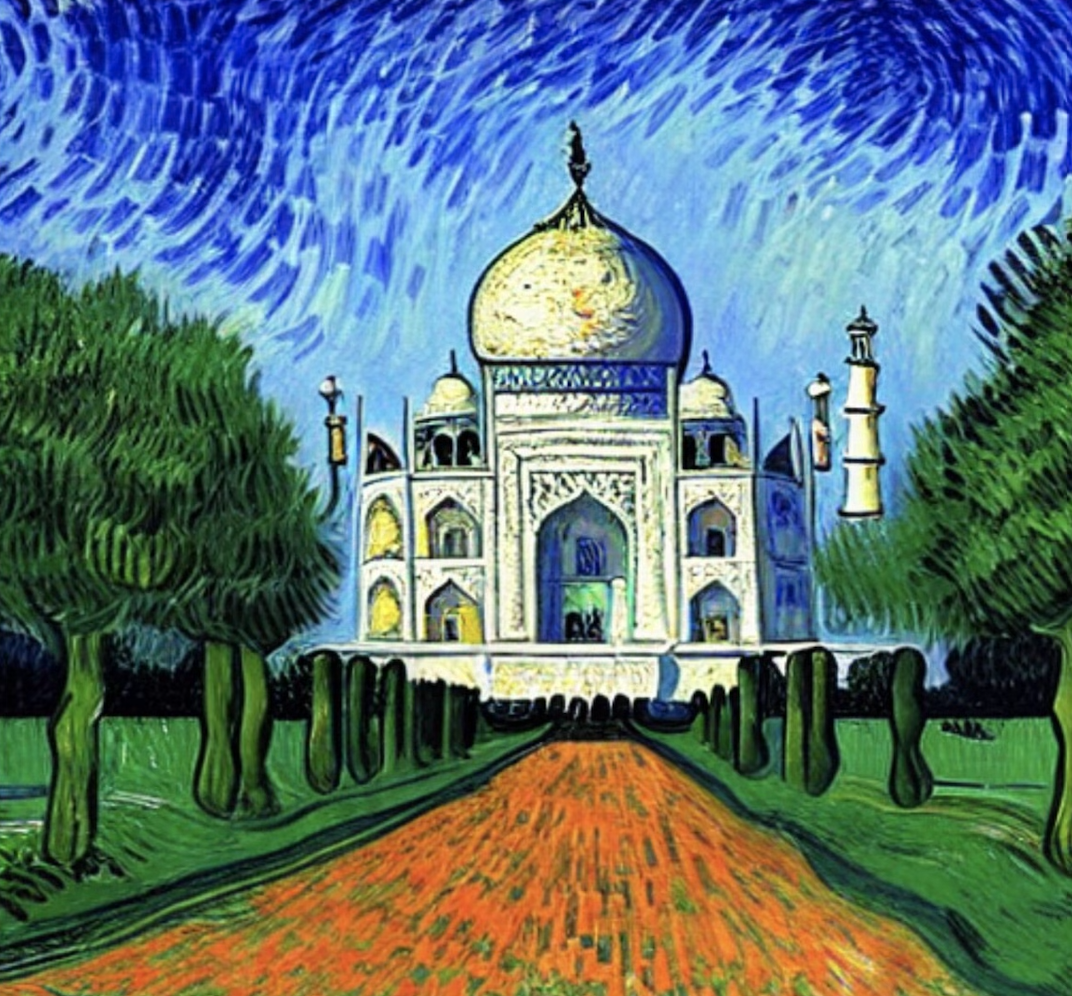

More recently, diffusion models have formed the backbone of several widely publicized generative systems. A notable example is DALL·E 2, introduced in Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents by Ramesh et al. (2022), which uses diffusion in a learned latent space to generate photorealistic images conditioned on natural language prompts. A high-level explanation of this system can be found in the blog post: How DALL·E 2 Actually Works by AssemblyAI. The following figure shows example images generated by a diffusion-based text-to-image model, illustrating how diverse, coherent visual concepts can be synthesized from natural language descriptions.

-

The success of these systems has sparked widespread interest among machine learning practitioners and researchers alike. Diffusion models are now routinely applied to problems in image synthesis, audio generation, video modeling, super-resolution, inpainting, and multimodal generation, often serving as the core generative component in large, modular pipelines.

-

From a conceptual standpoint, diffusion models are appealing because they combine several desirable properties:

- they are trained using simple regression-style objectives rather than adversarial losses,

- they admit clear probabilistic interpretations,

- and they scale reliably with model capacity and dataset size.

-

At the same time, diffusion models are flexible enough to incorporate a wide range of architectural choices, conditioning mechanisms, and sampling strategies. Modern implementations commonly integrate convolutional neural networks, attention mechanisms, transformers, and learned latent representations, while still adhering to the same underlying diffusion framework.

-

In this primer, we aim to demystify diffusion models by examining both their theoretical foundations and their practical implementation details. We begin by introducing the core principles that govern diffusion-based generative modeling, followed by a detailed exploration of the mathematical structure underlying diffusion processes. Building on this foundation, we then examine how diffusion models are instantiated in practice, including architectural design choices, training objectives, and sampling algorithms. Finally, we demonstrate how diffusion models can be implemented in PyTorch to generate images, providing concrete intuition for how these models operate end-to-end.

Introduction

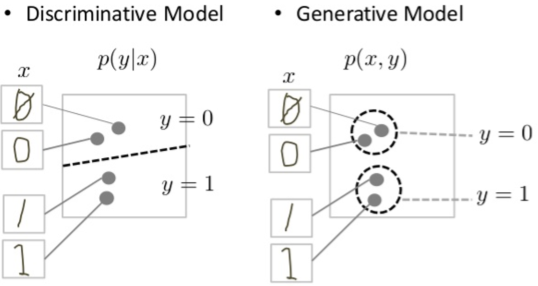

- Diffusion probabilistic models—commonly referred to as diffusion models—are a class of generative models designed to learn complex data distributions and generate new samples that resemble the training data. As generative models, their purpose is fundamentally different from that of discriminative models: rather than predicting labels or making decisions based on inputs, diffusion models aim to synthesize new data that are statistically similar to observed examples. For instance, a diffusion model trained on a dataset of animal images can generate novel images that appear to depict realistic animals, whereas a discriminative model would be tasked with classifying an image as containing a cat or a dog.

- The following figure shows a conceptual comparison between discriminative and generative modeling paradigms, highlighting how discriminative models learn decision boundaries for predicting labels, while generative models learn the joint data distribution in order to synthesize new samples.

-

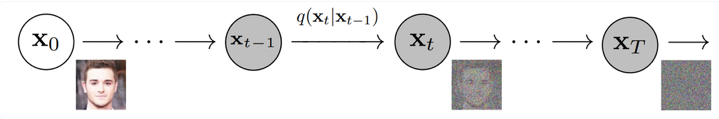

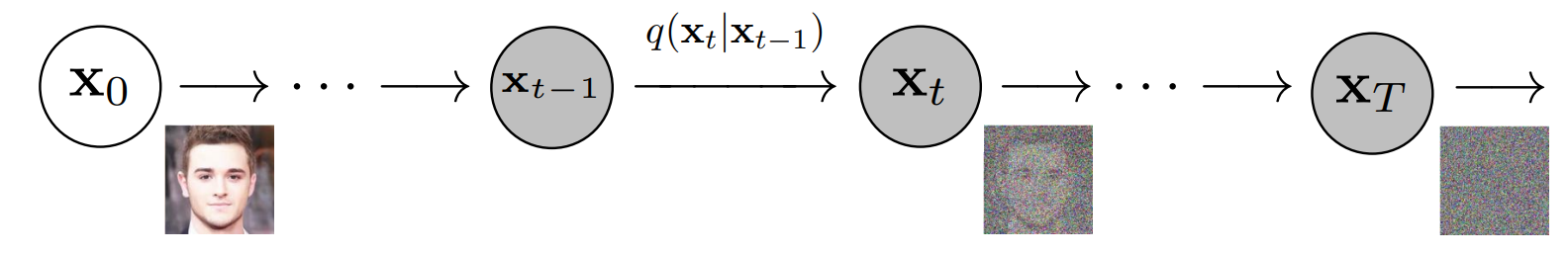

At a high level, diffusion models operate by defining two complementary stochastic processes:

- A fixed forward diffusion process, which progressively corrupts data by adding Gaussian noise, and

- A learned reverse denoising process, which is parameterized by a neural network and gradually removes noise in order to reconstruct data samples.

-

This formulation casts generative modeling as the problem of learning to invert a simple, fixed noising process. Starting from pure noise, the learned reverse process iteratively transforms noise into structured data. This perspective was formalized in Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics by Sohl-Dickstein et al. (2015) and later refined and popularized through more practical formulations.

-

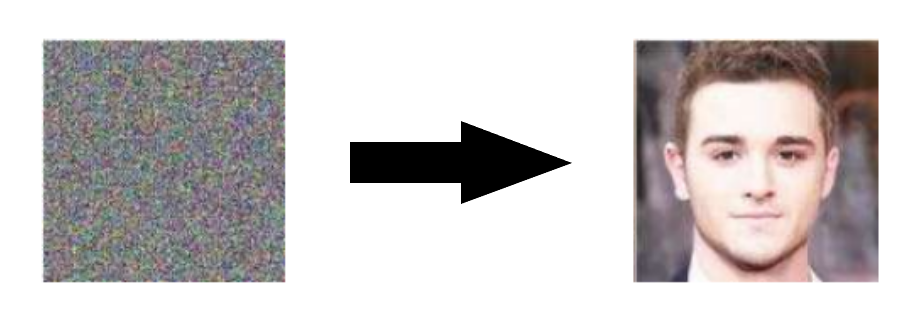

Conceptually, diffusion models can be understood as parameterized Markov chains trained to denoise data one step at a time. After training, generation proceeds by sampling an initial noise vector—often referred to as a latent tensor—and repeatedly applying the learned denoising transitions until a data sample is obtained. In this sense, diffusion models transform an unstructured collection of random numbers into a coherent output, such as an image, through a long sequence of small, incremental refinements.

-

Diffusion models are also closely related to several existing ideas in the generative modeling literature. They can be viewed as a form of latent variable model, in which the latent variables \(x_1, \ldots, x_T\) have the same dimensionality as the observed data \(x_0\). They share conceptual similarities with denoising autoencoders, which learn to reconstruct clean data from corrupted inputs, as discussed in A Connection Between Score Matching and Denoising Autoencoders by Vincent (2011). In addition, diffusion models are tightly connected to score-based generative modeling, where the goal is to estimate gradients of log-density functions rather than explicit likelihoods (cf. Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution by Song and Ermon (2019)).

-

The overall generation process is illustrated in the diagram below (source). The model begins from random noise and progressively refines the sample through repeated denoising steps.

-

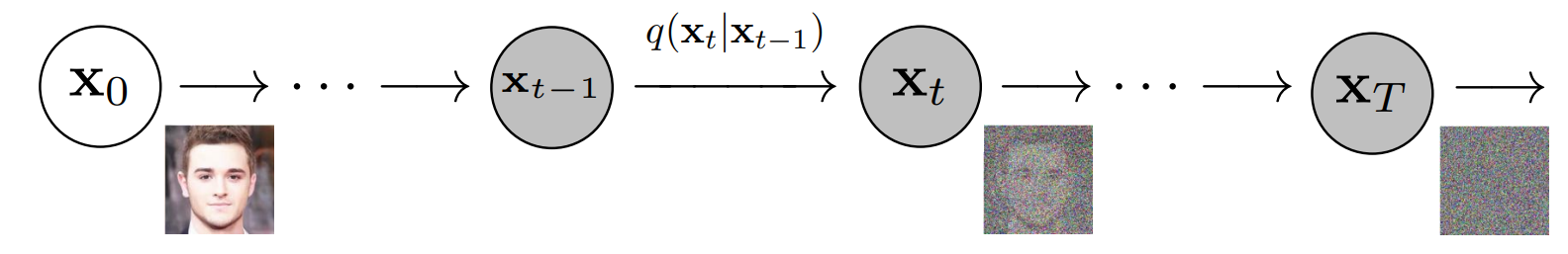

More formally, diffusion models define a latent-variable formulation in which a fixed Markov chain maps a data sample \(x_0\) to a sequence of progressively noisier variables \(x_1, \ldots, x_T\). The joint distribution of these variables under the forward process is denoted as:

\[q(x_{1:T} \mid x_0)\]- where each \(x_t\) has the same dimensionality as the original data. In the context of image generation, this corresponds to repeatedly adding small amounts of Gaussian noise to an image until the final variable \(x_T\) is approximately indistinguishable from isotropic Gaussian noise, meaning noise whose statistical properties are identical in all directions and dimensions.

-

This forward diffusion process is visualized below (source), with each step incrementally destroying structure in the data:

-

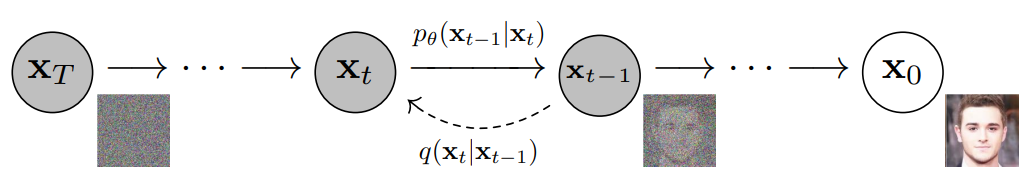

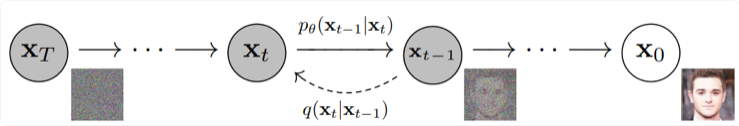

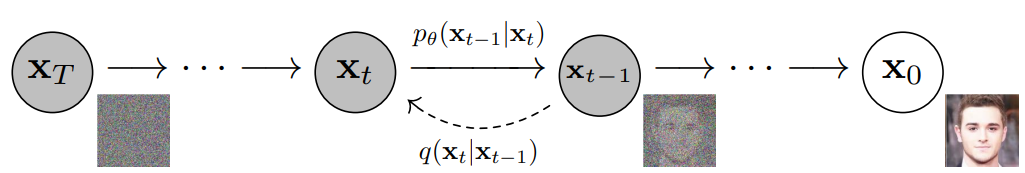

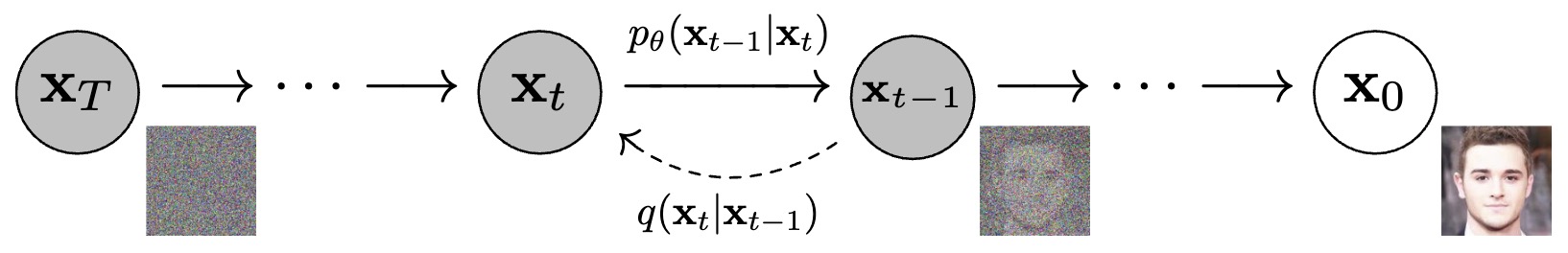

The objective of training a diffusion model is to learn the reverse process, denoted as:

\[p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\]- which approximates the inverse of each forward noising step. By traversing this learned reverse chain from \(t = T\) down to \(t = 0\), the model can transform pure noise into a structured data sample. This reverse-time generation process is illustrated below (source):

-

Under the hood, diffusion models rely on the Markov property, meaning that each state in the diffusion chain depends only on the immediately preceding (or following) state. A Markov chain is a stochastic process in which future states are conditionally independent of past states given the present state. This property allows diffusion models to decompose generation into a sequence of local transitions, each of which is relatively simple to model.

-

Key takeaway: diffusion models are constructed by first specifying a simple and tractable procedure for gradually turning data into noise, and then training a neural network to invert this procedure step-by-step. Each denoising step removes a small amount of noise and restores a small amount of structure. When this process is repeated sufficiently many times—starting from pure noise—the result is a coherent data sample. This deceptively simple idea underlies the remarkable effectiveness of diffusion models in modern generative modeling.

Transformers vs. Diffusion Models

- Transformers and diffusion models are two complementary families of generative models that differ primarily in (i) what conditional distribution they learn during training and (ii) how they generate samples at inference time, with modern systems increasingly mixing the two by using Transformer backbones inside diffusion pipelines (for example, Diffusion Transformer (DiT) in Scalable Diffusion Models with Transformers by Peebles and Xie (2022)).

- A detailed overview of the Transformer architecture has been offered in our Transformers primer.

High-level comparison

-

What is modeled:

- Transformers typically model a factorized (often autoregressive) likelihood over tokens, using self-attention as introduced in Attention Is All You Need by Vaswani et al. (2017).

- Diffusion models typically define a simple prior and learn a denoising reverse process that transforms noise into data, as in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020).

-

How samples are generated:

- Autoregressive Transformers sample sequentially, token-by-token, following the learned conditional factors (as scaled in large language models such as Language Models are Few-Shot Learners by Brown et al. (2020)).

- Diffusion models sample by starting from Gaussian noise and iteratively denoising over a sequence of timesteps (or continuous time), as in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020) and the continuous-time unification in Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations by Song et al. (2020).

Training objectives

-

Transformers: maximum-likelihood via token prediction:

-

A standard autoregressive objective is negative log-likelihood:

\[L_{\text{AR}}(\theta) =-\mathbb{E}_{x} \left[ \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log p_\theta(x_i \mid x_{<i}) \right]\]- which underpins large-scale decoder-only Transformers (for example, Language Models are Few-Shot Learners by Brown et al. (2020)).

-

A common non-autoregressive alternative is masked language modeling:

\[L_{\text{MLM}}(\theta) =-\mathbb{E}_{x,m} \left[ \sum_{i\in m} \log p_\theta(x_i \mid x_{\setminus m}) \right]\]- as in BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding by Devlin et al. (2018).

-

-

Diffusion: denoising / noise prediction:

-

A canonical DDPM training objective learns to predict the injected Gaussian noise:

\[L_{\text{DDPM}}(\theta) =\mathbb{E}_{x_0,t,\epsilon} \left[ \left\lVert \epsilon - \epsilon_\theta(x_t,t) \right\rVert^2 \right]\]- where \(x_t\) is a noised version of \(x_0\) and \(\epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0,I)\), as in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020).

-

In continuous-time score-based diffusion, the learned object is the score field that drives reverse-time dynamics, unifying diffusion and score matching in Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations by Song et al. (2020).

-

Sampling and computational trade-offs

-

Transformers:

- Sampling is typically sequential across tokens, which can be a bottleneck for long sequences even though each step is a single forward pass (as in Language Models are Few-Shot Learners by Brown et al. (2020)).

- For images, Transformers often require a tokenization scheme (e.g., patches or discrete codes) and then generate tokens sequentially; Transformers are widely used for vision representations via patch tokenization as in An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale by Dosovitskiy et al. (2020).

-

Diffusion models:

- Sampling is iterative across diffusion timesteps: starting from \(x_T \sim \mathcal{N}(0,I)\) and applying repeated denoising updates, as in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020).

- Accelerated samplers reduce the number of required steps by changing the sampling trajectory without changing training, as in Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models by Song et al. (2020), and continuous-time solvers offer SDE/ODE-based alternatives in Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations by Song et al. (2020).

Data modality fit

-

Transformers:

- Natural fit for discrete sequences (text, code), using attention for long-range dependencies as introduced in Attention Is All You Need by Vaswani et al. (2017).

- Strong for representation learning in vision via patch tokens, as in An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale by Dosovitskiy et al. (2020).

-

Diffusion models:

- Particularly strong for high-fidelity generation of continuous signals (images, audio, video), with likelihood-based, stable training in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020).

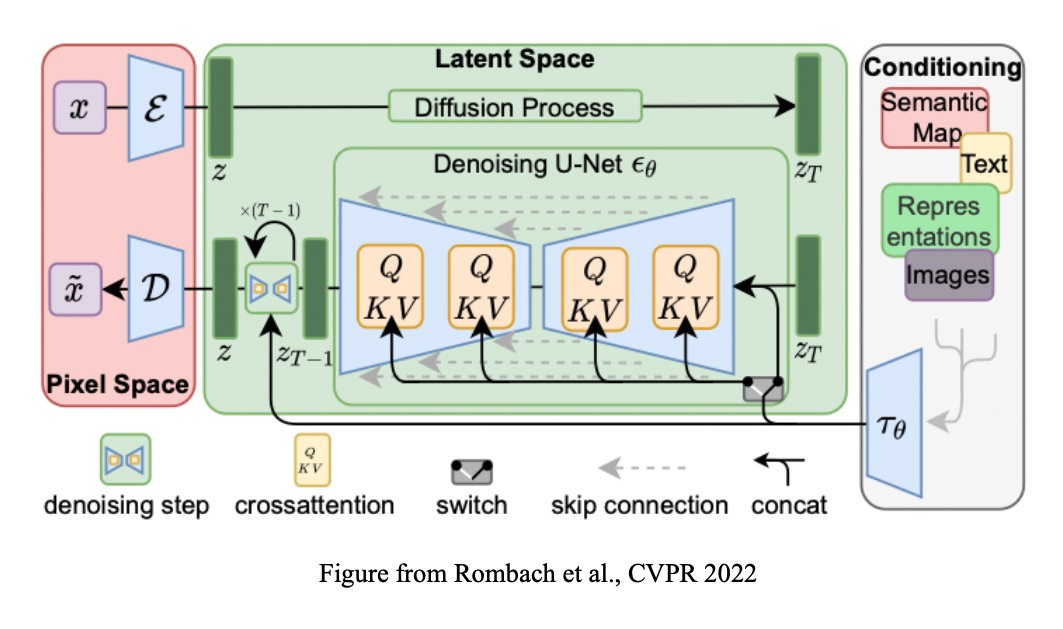

- Efficient large-scale image systems often run diffusion in a learned latent space for speed, as in High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models by Rombach et al. (2022).

Convergence: Transformer backbones inside diffusion

- A key modern trend is that “Transformer vs. diffusion” is often not an either-or choice: diffusion defines the generative process, while Transformers can serve as the denoiser backbone.

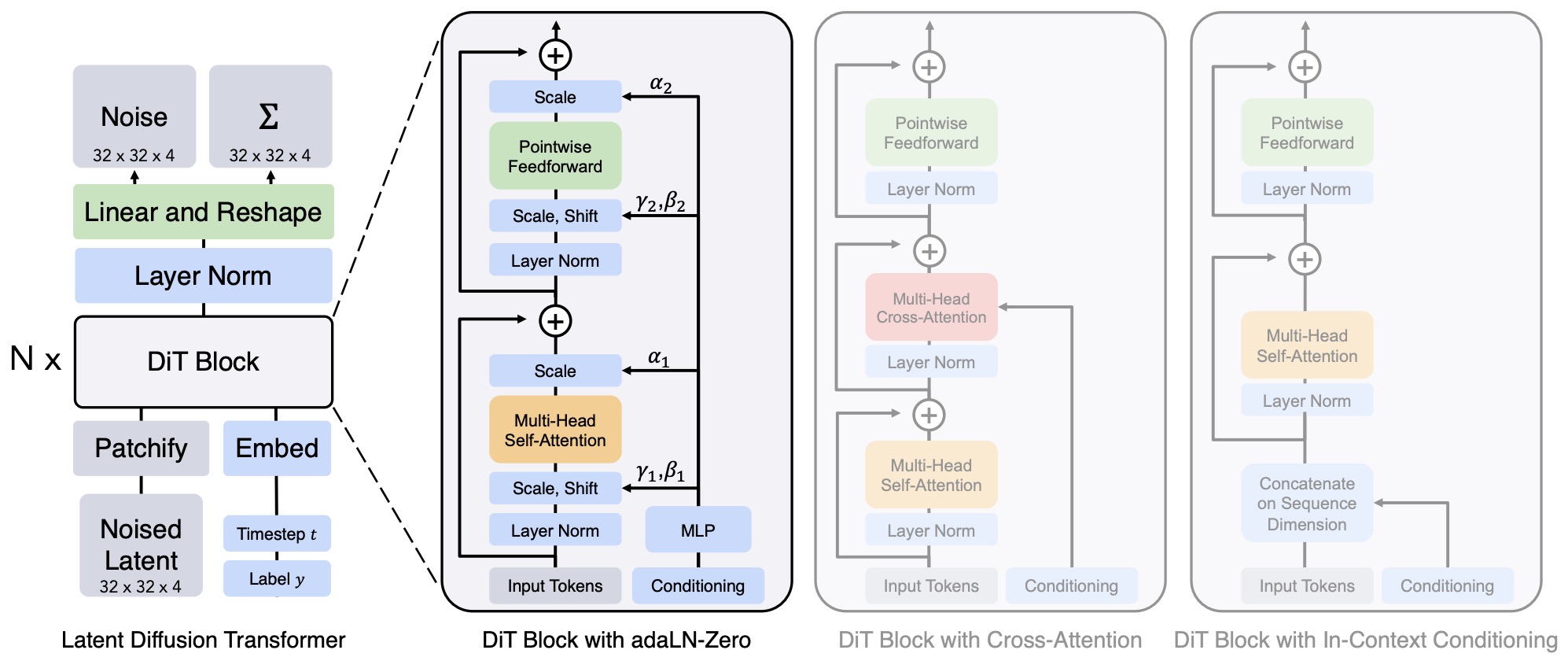

- DiT replaces the U-Net denoiser with a Transformer operating on latent patches and shows favorable scaling behavior, as in Scalable Diffusion Models with Transformers by Peebles and Xie (2022).

- In this setup, diffusion training still uses a denoising objective (e.g., noise prediction), but \(\epsilon_\theta(\cdot)\) is parameterized by a Transformer rather than a convolutional U-Net, as described in Scalable Diffusion Models with Transformers by Peebles and Xie (2022).

Advantages

- Diffusion models offer a combination of theoretical elegance, empirical performance, and practical robustness that has driven their rapid adoption across modern generative modeling applications. Their advantages span sample quality, training stability, scalability, and flexibility, positioning them as a compelling alternative to earlier generative paradigms such as GANs, VAEs, and flow-based models.

High-Fidelity Sample Quality

-

One of the most striking advantages of diffusion models is their ability to produce state-of-the-art sample quality, particularly in high-resolution image generation. Empirical evaluations have shown that diffusion models consistently achieve lower Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores than competing GAN-based approaches on standard benchmarks.

-

This result was demonstrated explicitly in Diffusion Models Beat GANs on Image Synthesis by Dhariwal and Nichol (2021), where diffusion models surpassed BigGAN-style architectures in both image fidelity and diversity. The figure below (source) illustrates the qualitative improvements achieved by diffusion-based generators:

- Unlike GANs, which often trade off diversity for sharpness due to adversarial dynamics, diffusion models naturally balance these objectives by modeling the full data distribution through a likelihood-based framework.

Stable and Non-Adversarial Training

-

Diffusion models avoid the instability inherent to adversarial training. GANs require carefully balanced updates between a generator and discriminator, and even minor imbalances can lead to divergence or mode collapse (cf. On the Convergence and Stability of GANs by Mescheder et al. (2018)). In contrast, diffusion models are trained using simple regression-style objectives, most commonly mean squared error losses that predict injected Gaussian noise.

-

This non-adversarial setup results in:

- predictable optimization behavior,

- reduced sensitivity to hyperparameters,

- and reliable convergence across a wide range of datasets and model scales.

-

As shown in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020), diffusion training objectives can be derived directly from variational likelihood bounds, providing both empirical stability and probabilistic justification.

Explicit Probabilistic Interpretation

-

Diffusion models admit a clear probabilistic interpretation grounded in latent-variable modeling and Markov chains. The forward diffusion process is fixed and analytically tractable, while the reverse process is learned to approximate the true reverse-time dynamics.

-

This structure enables:

- principled likelihood estimation (or lower bounds thereof),

- theoretical analysis using tools from stochastic processes,

- and direct connections to score matching and Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs).

-

In particular, the unification of diffusion models with continuous-time stochastic processes in Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations by Song et al. (2021) provides a rigorous mathematical framework that explains why diffusion-based approaches are effective and how different sampling methods relate to one another.

Scalability and Parallelization

-

Diffusion models scale exceptionally well with both model capacity and dataset size. Training can be parallelized efficiently across large batches and distributed systems because each training example involves independent noise corruption and denoising prediction.

-

Moreover, architectural choices such as U-Net-based or Transformer-based backbones can be incorporated without altering the core diffusion objective. This scalability has enabled diffusion models to serve as the backbone of large-scale systems such as:

- Imagen (cf. Photorealistic Text-to-Image Diffusion Models with Deep Language Understanding by Saharia et al. (2022)),

- DALL·E 2 (cf. Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents by Ramesh et al. (2022)),

- and Stable Diffusion developed by Stability AI.

Flexibility Across Modalities and Conditioning Schemes

-

Diffusion models are highly adaptable and have been successfully applied to a wide range of data modalities, including images, audio, video, 3D data, and multimodal settings. Conditioning mechanisms—such as class labels, text embeddings, semantic maps, or other structured inputs—can be integrated naturally via concatenation, cross-attention, or feature-wise modulation.

-

This flexibility is exemplified by models such as GLIDE proposed in GLIDE: Towards Photorealistic Image Generation and Editing with Text-Guided Diffusion Models by Nichol et al. (2021), and Latent Diffusion Models proposed in High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models by Rombach et al. (2022).

-

Because the diffusion objective remains unchanged, these conditioning strategies can be added without destabilizing training.

Definitions

- This section introduces the core concepts and components that recur throughout diffusion-based generative modeling. These definitions establish a shared vocabulary for understanding diffusion models at both a theoretical and practical level.

Diffusion Models

-

Diffusion models are neural generative models that learn to approximate the reverse of a stochastic diffusion process. Concretely, a diffusion model parameterizes conditional distributions of the form:

\[p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\]- where \(x_t\) denotes a noisy version of the data at diffusion timestep \(t\), and \(\theta\) denotes the learnable parameters of the model. The objective is to iteratively transform noisy inputs into cleaner ones until a final sample \(x_0\) is obtained.

-

Diffusion models are typically trained end-to-end to denoise corrupted inputs and produce continuous outputs such as images, audio waveforms, or video frames. Unlike GANs, diffusion models do not rely on adversarial objectives, and unlike flow-based models, they do not require invertible architectures.

-

From an architectural perspective, diffusion models can employ any neural network whose input and output dimensionalities match. In practice, U-Net–style architectures, originally proposed in U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation by Ronneberger et al. (2015), dominate due to their ability to preserve spatial structure while integrating global context via skip connections and attention mechanisms. Variants include conditional U-Nets, 3D U-Nets for video or volumetric data, and transformer-based U-Nets for large-scale multimodal generation.

Forward and Reverse Processes

-

Diffusion models consist of two coupled stochastic processes:

- a forward (diffusion) process, which progressively adds noise to data, and

- a reverse (denoising) process, which is learned by the model.

-

The forward process is fixed and typically defined as a Markov chain with Gaussian transitions. The reverse process is parameterized by a neural network and trained to approximate the true reverse-time dynamics. This formulation was introduced in Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics by Sohl-Dickstein et al. (2015) and refined in later works such as Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020).

Schedulers

-

Schedulers define how noise is added and removed over time during both training and inference. Formally, a scheduler specifies:

- the noise variance schedule \({\beta_t}_{t=1}^T\) or its continuous-time analogue,

- how to compute intermediate quantities such as \(\alpha_t = 1 - \beta_t\) and \(\bar{\alpha}_t = \prod_{s=1}^t \alpha_s\),

- and how to map model predictions to the previous timestep during sampling.

-

Schedulers are algorithmic components rather than neural networks, and they play a critical role in controlling sample quality, stability, and efficiency.

-

Prominent schedulers and samplers include:

- DDPM: introduced in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020),

- DDIM: introduced in Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models by Song et al. (2020),

- PNDM: proposed in Pseudo Numerical Methods for Diffusion Models on Manifolds by Liu et al. (2022),

- DEIS: introduced in Fast Sampling of Diffusion Models with Discrete Exponential Integrators by Zhang and Chen (2022).

-

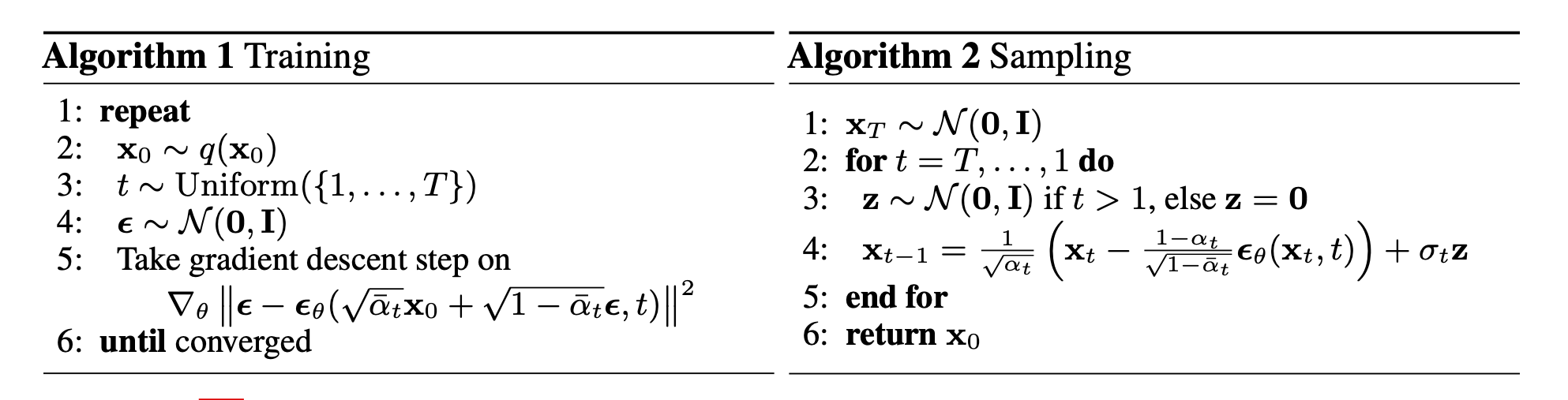

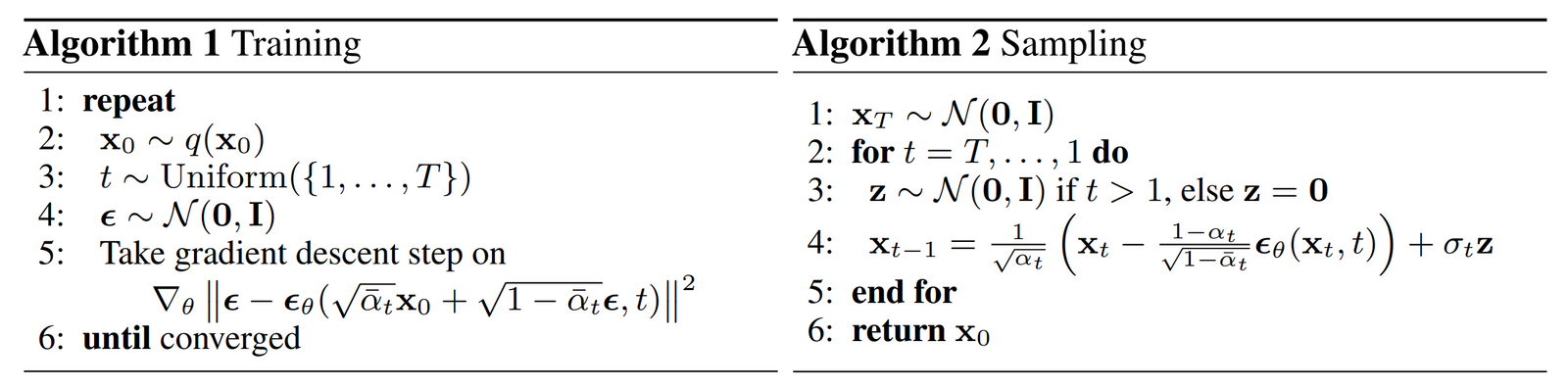

The figure below, adapted from Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020), illustrates the interaction between training and sampling algorithms governed by the scheduler:

Training and Sampling Pipelines

-

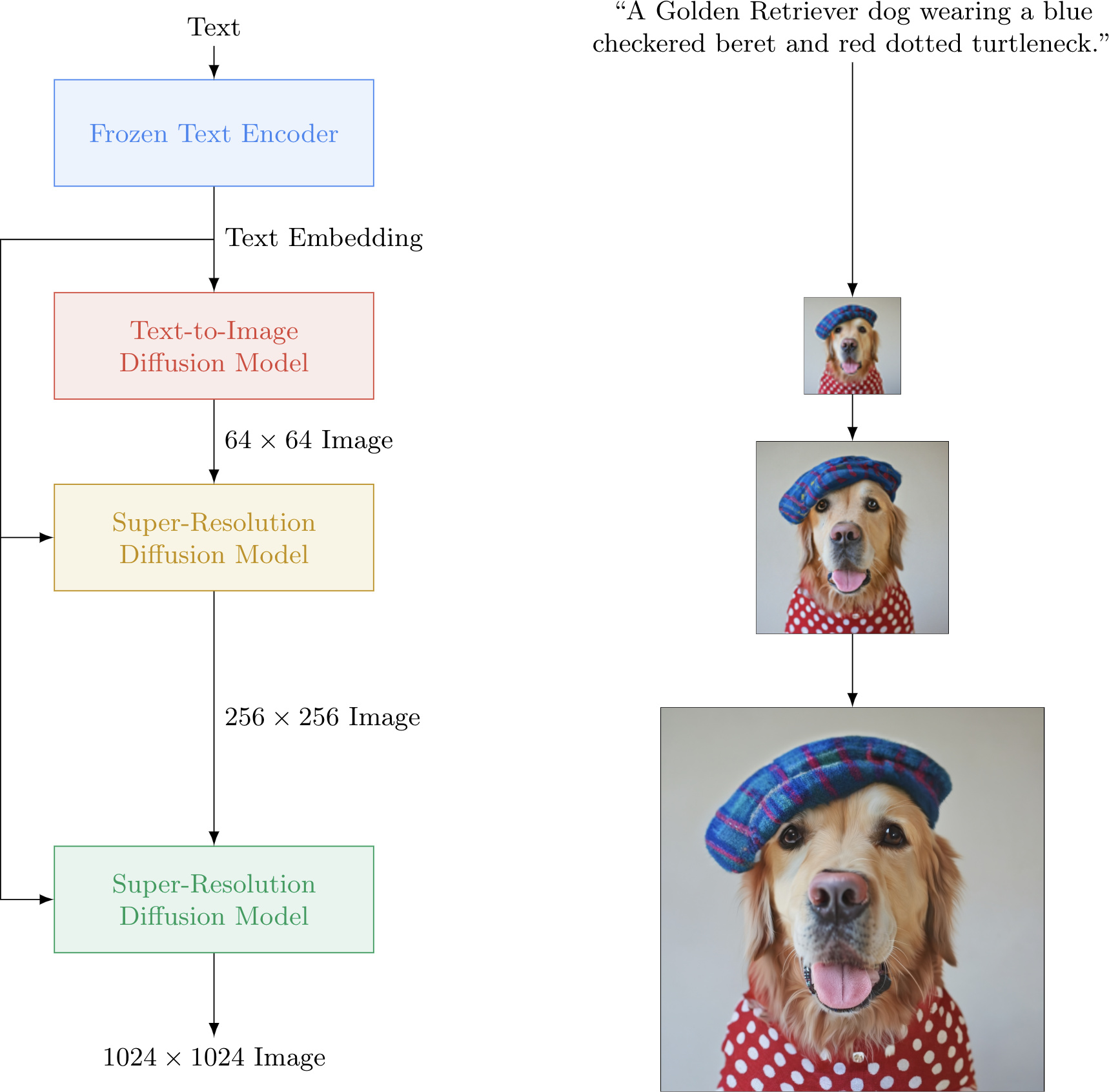

In practical systems, diffusion models are rarely deployed in isolation. Instead, they are embedded within end-to-end diffusion pipelines that combine multiple components, such as:

- diffusion models operating at different resolutions,

- text or class encoders for conditional generation,

- super-resolution or refinement models,

- and post-processing stages.

-

These pipelines orchestrate training and inference across multiple models and noise schedules to achieve high-quality generation at scale.

-

Well-known examples include:

- GLIDE GLIDE: Towards Photorealistic Image Generation and Editing with Text-Guided Diffusion Models by Nichol et al. (2021),

- Latent Diffusion Models High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models by Rombach et al. (2022),

- Imagen Photorealistic Text-to-Image Diffusion Models with Deep Language Understanding by Saharia et al. (2022),

- DALL·E 2 Hierarchical Text-Conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents by Ramesh et al. (2022).

-

A high-level overview of such a pipeline is shown below (figure adapted from Imagen):

Takeaways

- Diffusion models learn to reverse a fixed noising process via neural denoising.

- Schedulers control the temporal dynamics of noise injection and removal.

-

Sampling pipelines integrate diffusion models with encoders, decoders, and conditioning mechanisms to enable large-scale generation.

- These definitions provide the conceptual building blocks required to understand the mathematical theory of diffusion models, which we examine next.

Diffusion Models: The Theory

- This section develops the theoretical foundations of diffusion models at a conceptual level. Rather than reproducing detailed derivations, we focus on how diffusion models are structured, why they are mathematically well-founded, and how their design choices connect probabilistic modeling, stochastic processes, and modern neural networks. Formal derivations and exact equations are deferred to The Math Under-the-Hood section.

Diffusion Models as Latent-Variable Generative Models

-

Diffusion models belong to the class of latent-variable generative models, meaning that observed data are assumed to arise from a sequence of unobserved random variables. Unlike traditional latent-variable models such as Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), diffusion models introduce a high-dimensional latent trajectory in which every latent variable has the same dimensionality as the observed data.

-

The theoretical motivation for this construction was first introduced in Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics by Sohl-Dickstein et al. (2015), which framed generation as the reversal of a gradual entropy-increasing process. This idea was later made computationally practical and scalable in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020).

-

At a high level, diffusion models define:

- A forward process that gradually destroys information in the data by injecting noise.

- A reverse process that learns to recover data by removing noise step by step.

-

This framing transforms generation into a sequence of local denoising problems, each of which is significantly easier than modeling the full data distribution in a single step.

Markovian Structure and Tractability

-

A defining theoretical assumption of diffusion models is the Markov property: each latent variable depends only on its immediate predecessor (in the forward process) or successor (in the reverse process). This choice has several important consequences:

- It enables a clean factorization of joint probability distributions.

- It allows likelihood-based training using variational inference.

- It ensures that learning and sampling can be performed with bounded memory and computation per timestep.

-

The Markov structure is not merely a modeling convenience; it is essential for making diffusion models analytically tractable and numerically stable. By restricting dependencies to adjacent timesteps, diffusion models avoid the intractable posterior dependencies that often plague deep latent-variable models.

Fixed Forward Process and Learned Reverse Process

-

From a theoretical perspective, one of the most elegant aspects of diffusion models is the asymmetry between the forward and reverse processes:

- The forward diffusion process is fixed and known, chosen by the model designer.

- The reverse diffusion process is unknown and learned, parameterized by a neural network.

-

This asymmetry is crucial. Because the forward process is analytically defined, it induces a known family of corrupted data distributions. The learning problem then reduces to approximating how these corrupted distributions should be inverted.

-

This idea was central to the reformulation of diffusion models in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020), which showed that learning the reverse process can be cast as a series of regression problems with known targets.

Likelihood-Based Training via Variational Inference

-

Diffusion models are explicit likelihood models. Unlike GANs, which rely on implicit distributions and adversarial training, diffusion models optimize a well-defined objective derived from probability theory.

-

Training proceeds by maximizing a variational lower bound (ELBO) on the data log-likelihood. Conceptually, this objective measures how well the learned reverse process approximates the true reverse of the forward diffusion.

-

The theoretical importance of this formulation is threefold:

- It provides a principled objective grounded in statistical inference.

- It ensures that diffusion models are comparable using likelihood-based metrics.

- It allows training to decompose into a sum of independent per-timestep terms.

-

The use of Gaussian distributions in both forward and reverse processes ensures that all divergence terms appearing in the ELBO are analytically tractable, avoiding the need for high-variance Monte Carlo estimators.

Noise Prediction Parameterization

-

A key theoretical and practical insight introduced in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020) is that the reverse process need not be parameterized directly in terms of probability distributions.

-

Instead, the model can be trained to predict the noise component that was added during the forward process. This reparameterization has deep theoretical implications:

- It implicitly trains the model to estimate the score function of noisy data distributions.

- It connects diffusion models to denoising score matching, originally developed in Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution by Song and Ermon (2019).

- It yields a simple mean-squared-error objective that is stable across noise levels.

-

This perspective reveals that diffusion models and score-based generative models are not separate paradigms, but rather different parameterizations of the same underlying probabilistic structure.

Connection to Continuous-Time/Score-Based Models

-

Although this section focuses on discrete-time diffusion models, the theory naturally extends to continuous-time formulations. In particular:

- Discrete-time diffusion models can be viewed as numerical discretizations of continuous stochastic processes.

- Learning to predict noise is equivalent to learning the score of a time-dependent distribution.

- Sampling procedures correspond to solving stochastic or deterministic differential equations.

-

These connections were formalized in Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations by Song et al. (2021), which unified DDPMs, DDIMs, and score-based models under a single SDE-based framework.

Discrete Data and Final Decoding

-

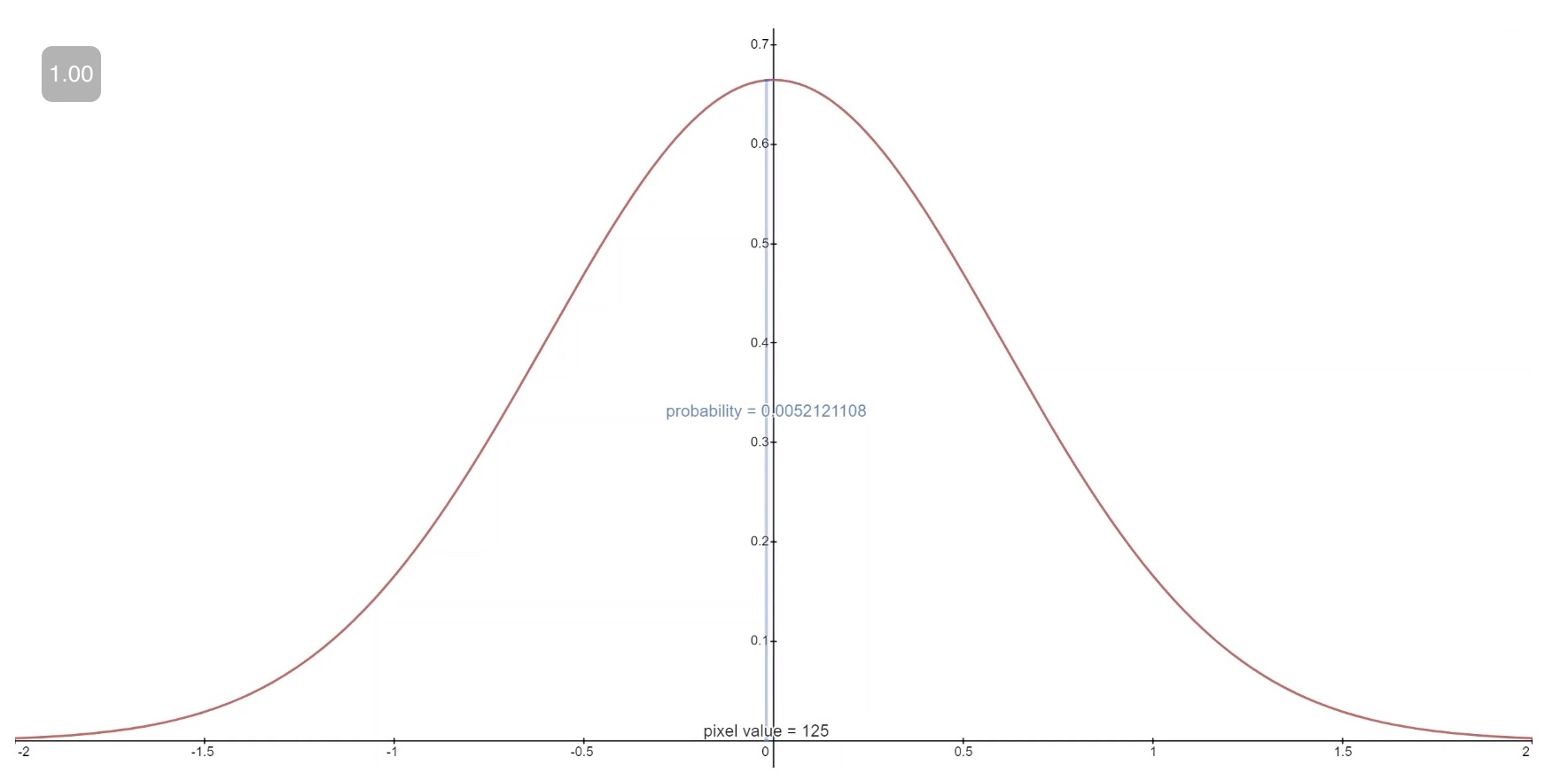

A final theoretical consideration concerns the generation of discrete-valued data, such as pixel intensities. While diffusion operates in continuous space, the final output must correspond to discrete observations.

-

Diffusion models address this by defining an explicit likelihood for the final denoising step, typically using discretized continuous distributions. This ensures that diffusion models remain fully probabilistic and that likelihood evaluation is well-defined even for discrete domains.

Takeaways

-

At a theoretical level, diffusion models are characterized by:

- A fixed, analytically tractable forward corruption process.

- A learned reverse denoising process with local dependencies.

- A likelihood-based variational training objective.

- A noise-prediction parameterization linked to score matching.

- A natural extension to continuous-time stochastic processes.

-

These properties collectively explain why diffusion models combine strong theoretical guarantees with exceptional empirical robustness, providing a solid foundation for the architectural and algorithmic design choices explored in subsequent sections.

Diffusion Models: A Deep Dive

- This section connects the theoretical formulation of diffusion models to their concrete operational behavior. We unpack how the forward and reverse processes interact during training and sampling, providing intuition for why diffusion models are effective and how their components work together in practice.

Overview

-

Diffusion models are a form of latent variable model, in which observed data are associated with a sequence of latent states that progressively increase in noise. Latent variable models aim to describe complex data distributions by introducing hidden variables that capture underlying structure in a continuous space, as discussed in Latent Variable Models by The AI Summer.

-

In diffusion models, however, the latent variables \(x_1, \ldots, x_T\) are not lower-dimensional abstractions of the data. Instead, they share the same dimensionality as the observed variable \(x_0\) and represent progressively noisier versions of it. The latent space in diffusion models therefore corresponds to different noise levels rather than semantic compression.

-

Diffusion models consist of two tightly coupled processes:

- A forward diffusion process \(q\) that gradually adds noise to data.

- A reverse denoising process \(p_\theta\) that learns to remove this noise step-by-step.

-

The forward process is fixed by design, while the reverse process is parameterized by a neural network and learned from data.

Forward Diffusion Process

-

The forward process defines a Markov chain that incrementally corrupts a clean data sample \(x_0\). At each timestep \(t\), Gaussian noise is added according to a predefined variance schedule \({\beta_t}_{t=1}^T\).

-

Formally, the forward process is defined as:

\[q(x_t \mid x_{t-1}) =N\left( x_t; \sqrt{1 - \beta_t} x_{t-1}, \beta_t I \right)\]- where \(\beta_t\) controls the magnitude of noise added at step \(t\).

-

Repeating this process for sufficiently large \(T\) ensures that the final variable \(x_T\) is approximately distributed as an isotropic Gaussian:

\[q(x_T) \approx N(0, I)\] -

A key practical insight, introduced in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020), is that the forward process admits a closed-form solution for sampling \(x_t\) directly from \(x_0\):

\[x_t =\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} , x_0 +\sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim N(0, I)\]- with \(\bar{\alpha}_t = \prod_{s=1}^t (1 - \beta_s)\). This property allows efficient training by randomly sampling timesteps without explicitly simulating the full forward chain.

-

The forward diffusion process is illustrated below (source), where structured data are gradually transformed into noise through a sequence of small Gaussian perturbations:

Reverse Denoising Process

-

The reverse process is the core learned component of a diffusion model. Its purpose is to invert the forward diffusion dynamics by progressively removing noise.

-

Starting from pure noise \(x_T \sim N(0, I)\), the model applies a sequence of learned reverse transitions:

- Each reverse transition is parameterized as a Gaussian distribution:

-

In practice, the variance \(\Sigma_\theta\) is often fixed or chosen from a small set of options, while the mean \(\mu_\theta\) is predicted by a neural network conditioned on both the noisy input \(x_t\) and the timestep \(t\).

-

This reverse process is illustrated below (source), where noise is gradually transformed back into a structured sample:

Training Procedure and Intuition

-

Training a diffusion model involves teaching the neural network how to denoise inputs at all noise levels. The training loop proceeds as follows:

- Sample a clean data point \(x_0 \sim q(x_0)\).

- Sample a timestep \(t\) uniformly from \({1, \ldots, T}\).

- Sample noise \(\epsilon \sim N(0, I)\).

- Construct a noisy input \(x_t\) using the closed-form forward process.

- Train the network to predict the noise \(\epsilon\) from \(x_t\) and \(t\).

-

This procedure is repeated across batches of data using stochastic gradient descent. Importantly, the network learns a local denoising rule at each timestep rather than a global mapping from noise to data.

Noise Prediction and Score Estimation

- Modern diffusion models are almost always trained to predict the injected noise \(\epsilon\) rather than directly predicting the clean data \(x_0\) or the reverse-process mean. The corresponding loss function is:

-

This formulation has several advantages:

- It yields stable gradients across timesteps.

- It avoids scale issues at high noise levels.

- It connects diffusion models to denoising score matching, as shown in Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution by Song and Ermon (2019).

-

Intuitively, predicting noise is equivalent to estimating the direction in which a noisy sample should be moved to increase data likelihood.

Sampling and Generation

- After training, generation proceeds by initializing \(x_T \sim N(0, I)\) and repeatedly applying the learned reverse transitions:

-

Each step removes a small amount of noise and restores structure. After \(T\) steps, the final output \(x_0\) is obtained.

-

While this procedure yields high-quality samples, it is computationally expensive due to the large number of sequential steps. This limitation motivated the development of accelerated samplers such as DDIM Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models by Song et al. (2020) and ODE-based solvers derived from continuous-time diffusion theory.

Practical Insights

-

From a practical standpoint, diffusion models succeed because they:

- decompose generation into many simple denoising steps,

- train a single network to handle all noise levels,

- and leverage a fixed, well-behaved forward corruption process.

-

This design transforms a challenging generative modeling problem into a sequence of tractable regression tasks, explaining both the robustness and the scalability of diffusion-based approaches.

The Math Under-the-Hood

- At the core of diffusion models lies a probabilistic construction based on Markov chains, Gaussian perturbations, and variational inference. A diffusion model defines a structured latent-variable model in which data are progressively corrupted by noise through a fixed forward process, and then reconstructed through a learned reverse process. This formulation was first proposed in Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics by Sohl-Dickstein et al. (2015) and later refined into a practical and scalable framework in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020).

Forward Diffusion Process (Noising)

-

The forward diffusion process is a fixed, non-learned stochastic process that gradually destroys structure in the data by adding Gaussian noise. Let \(x_0 \sim q(x_0)\) denote a data sample drawn from the unknown data distribution. The forward process defines a sequence of latent variables \(x_1, \ldots, x_T\) such that each variable is obtained by perturbing the previous one with a small amount of noise.

-

Formally, the forward process is defined as a Markov chain with Gaussian transition kernels:

\[q\left(x_{1:T} \mid x_0\right) := \prod_{t=1}^{T} q\left(x_t \mid x_{t-1}\right) := \prod_{t=1}^{T} N\left( x_t; \sqrt{1-\beta_t}x_{t-1}, \beta_t I \right)\]-

where:

- \(\beta_t \in (0,1)\) is a variance schedule controlling the amount of noise added at timestep \(t\),

- \(I\) is the identity covariance matrix,

- and \(T\) is the total number of diffusion steps.

-

-

The variance schedule \({\beta_t}_{t=1}^T\) is chosen such that noise increases monotonically over time. For sufficiently large \(T\) and a well-behaved schedule, the final latent variable \(x_T\) converges in distribution to an isotropic Gaussian:

-

A crucial property of this construction, derived in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020), is that the marginal distribution \(q(x_t \mid x_0)\) admits a closed-form expression:

\[x_t =\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t}x_0 +\sqrt{1-\bar{\alpha}_t}\epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim N(0, I),\]-

where:

\[\alpha_t = 1 - \beta_t, \qquad \bar{\alpha}_t = \prod_{s=1}^{t} \alpha_s\]

-

-

This result allows direct sampling of \(x_t\) from \(x_0\) at any timestep \(t\) without explicitly simulating the entire forward chain, which is critical for efficient training.

-

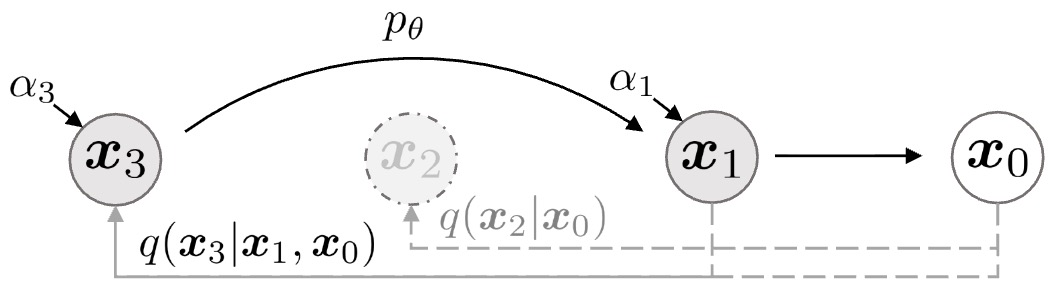

The joint structure of the forward diffusion process is visualized below (figure adapted from Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020)):

Reverse Diffusion Process (Denoising)

-

The generative power of diffusion models arises from learning the reverse diffusion process, which inverts the forward noising dynamics. While the forward process is analytically defined, the true reverse process \(q(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\) is generally intractable. Diffusion models therefore learn a parametric approximation to this reverse process.

-

The learned generative model defines the joint distribution:

\[p_\theta(x_{0:T}) := p(x_T) \prod_{t=1}^{T} p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\]- where the prior over the final latent variable is fixed as:

-

Each reverse transition is parameterized as a Gaussian:

\[p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t) =N\left( x_{t-1}; \mu_\theta(x_t, t), \Sigma_\theta(x_t, t) \right)\]-

with:

- \(\mu_\theta(x_t, t)\) denoting the predicted mean,

- \(\Sigma_\theta(x_t, t)\) denoting the predicted or fixed covariance,

- and \(\theta\) representing the parameters of a neural network conditioned on \(x_t\) and the timestep \(t\).

-

-

The Markov property plays a crucial role here: each reverse transition depends only on the current noisy state \(x_t\) and not on earlier or later latent variables. This conditional independence enables tractable likelihood bounds and efficient training.

-

The reverse diffusion chain is illustrated below (figure adapted from Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020)):

Variational Learning Perspective

-

Training diffusion models is framed as variational inference, because the intractable true posterior \(p_\theta(x_{1:T}\mid x_0)\) is replaced by a parameterized, tractable variational distribution \(q(x_{1:T}\mid x_0)\) whose parameters are optimized to tighten a variational (evidence) lower bound, also called the ELBO, on the data log-likelihood:

\[\log p_\theta(x_0) \ge \mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T}\mid x_0)} \left[ \log p_\theta(x_{0:T}) -\log q(x_{1:T}\mid x_0) \right] \equiv \mathcal{L}_{\text{VLB}}\]- where:

- \(x_0\) denotes an observed data sample.

- \(x_{1:T}\) denotes the sequence of latent variables (noise states) along the diffusion trajectory.

- \(p_\theta(x_{1:T}\mid x_0)\) is the true (intractable) posterior, representing the distribution over latent diffusion trajectories given data.

- \(q(x_{1:T}\mid x_0)\) is the variational posterior, a tractable approximation to the true posterior constructed from the known forward noising process.

- \(p_\theta(x_{0:T})\) is the joint generative model,

- Factorized as: \(p_\theta(x_{0:T}) = p(x_T)\prod_{t=1}^{T} p_\theta(x_{t-1}\mid x_t)\)

- With prior: \(p(x_T)=\mathcal{N}(0,I)\)

- \(\log p_\theta(x_{0:T})\) measures how well a latent trajectory explains the data under the model.

- \(\log q(x_{1:T}\mid x_0)\) penalizes divergence from the variational posterior.

- \(\mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T}\mid x_0)}[\cdot]\) denotes expectation over diffusion trajectories sampled from the variational posterior.

- \(\mathcal{L}_{\text{VLB}}\) is the variational (evidence) lower bound on \(\log p_\theta(x_0)\).

- where:

-

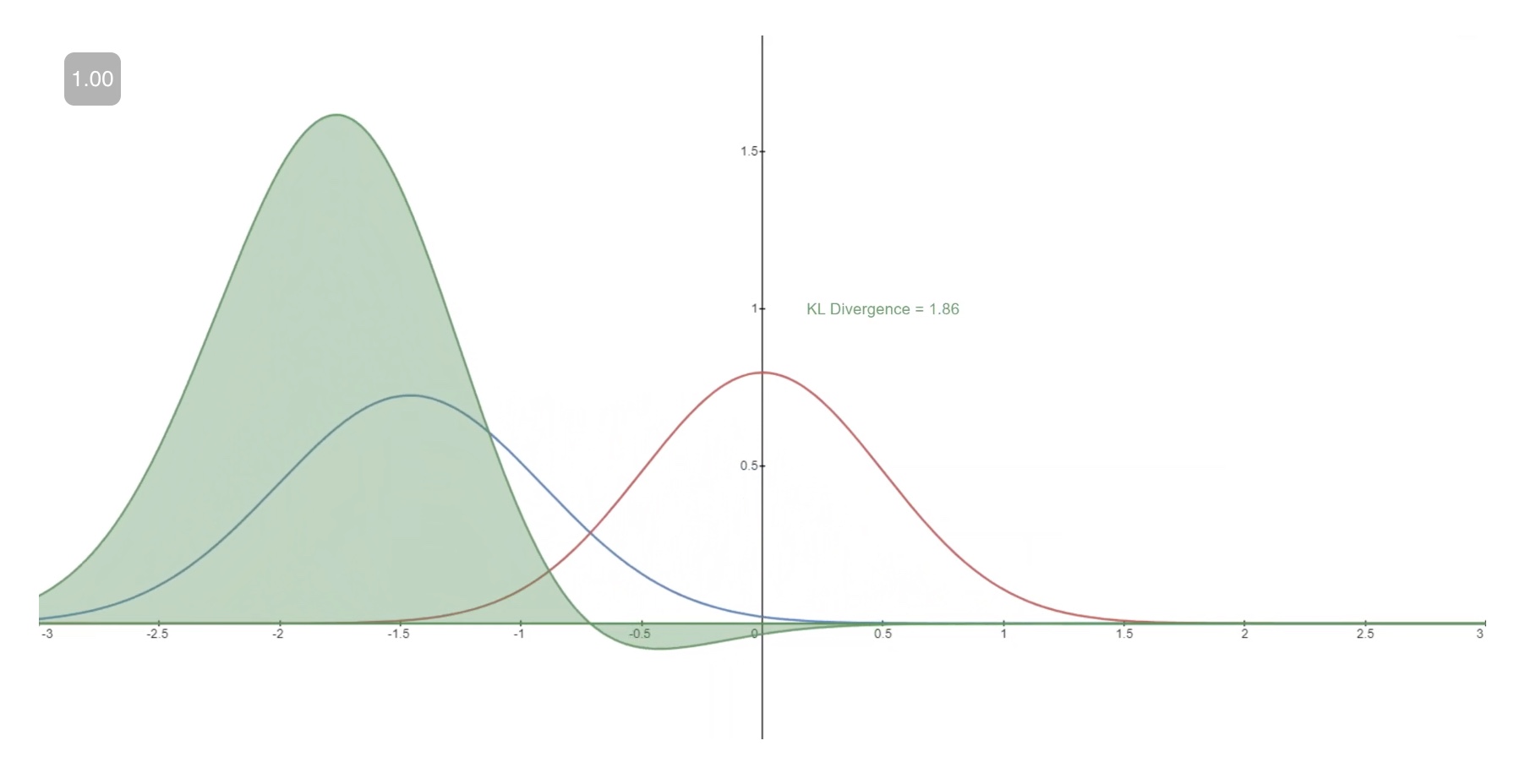

Due to the Markov structure and Gaussian assumptions, the ELBO decomposes into a sum of Kullback–Leibler divergence terms between forward and reverse transition distributions, plus a reconstruction term at the final step:

- Because both the forward and reverse transitions are Gaussian, all KL divergence terms admit closed-form expressions. This tractability distinguishes diffusion models from many other latent-variable models and avoids reliance on high-variance Monte Carlo estimators.

Noise Prediction Parameterization

- A key empirical insight introduced in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020) is that training becomes significantly simpler and more stable when the model is parameterized to predict the noise \(\epsilon\) rather than the reverse-process mean directly.

- Predicting the reverse-process mean \(\mu_\theta(x_t,t)\) requires the model to explicitly account for the noise schedule and the time-dependent correlations between \(x_t\) and \(x_0\), making the learning target vary in scale and structure across timesteps. In contrast, predicting the noise \(\epsilon\) yields a fixed, well-conditioned target drawn from a simple isotropic Gaussian distribution at all timesteps, meaning the noise has identical variance in every dimension and no preferred direction or correlation structure, i.e., its covariance matrix is proportional to the identity.

- Direct mean prediction appears in early diffusion formulations such as Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics by Sohl-Dickstein et al. (2015) and as an explicit parameterization option in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020), but it has been largely superseded in practice by noise prediction in modern U-Net–based diffusion models (e.g., DDPMs and LDMs) and Transformer-based diffusion architectures (e.g., DiTs), due to improved stability and empirical performance.

- Under this parameterization, the neural network \(\epsilon_\theta(x_t, t)\) is trained to approximate the noise used to generate \(x_t\):

-

This yields the widely used simplified training objective:

\[L_{\text{simple}}(\theta) =\mathbb{E}_{x_0, t, \epsilon} \left[ \left\lVert \epsilon -\epsilon_\theta(x_t, t) \right\rVert^2 \right]\]- where \(t\) is sampled uniformly from \({1,\ldots,T}\) and \(\epsilon \sim N(0, I)\).

-

This objective can be interpreted as a form of denoising score matching, establishing a direct connection between diffusion models and score-based generative modeling, as shown in Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution by Song and Ermon (2019).

Takeaways

-

In summary, the mathematical foundation of diffusion models rests on:

- a fixed Gaussian forward diffusion process,

- a learned Gaussian reverse process parameterized by neural networks,

- a variational likelihood objective composed of tractable KL divergences,

- and a noise-prediction parameterization that yields stable and efficient training.

-

This combination of probabilistic rigor and practical simplicity explains why diffusion models are both theoretically well-grounded and empirically successful, and it sets the stage for understanding architectural choices and sampling algorithms in subsequent sections.

Taxonomy of Diffusion Models

-

At a high level, diffusion models can be categorized along two largely orthogonal axes:

- Time formulation: discrete-time versus continuous-time diffusion.

- Representation space: pixel space, latent space, or other learned representations.

-

Historically, the modern diffusion literature emerged in two closely related but initially distinct lines of work. An important precursor is Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics by Sohl-Dickstein et al. (2015), which introduced a discrete-time, pixel-space gradual noising and denoising framework closely resembling modern diffusion models. Building on this idea, Score-Based Generative Models (SGMs) were introduced in continuous time as a noise-conditional score estimation framework in Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution by Song and Ermon (2019). Shortly thereafter, Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) were proposed in a discrete-time variational framework in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020). These two perspectives were later shown to be mathematically unified under a continuous-time SDE formulation in Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations by Song et al. (2021).

-

In their most common and practically deployed form, diffusion models are discrete-time models, where noise is added and removed over a finite sequence of timesteps (\(t \in {1,\dots,T}\)). Within this class, diffusion is typically implemented either directly in pixel space or in a learned latent space.

-

More precisely, modern diffusion models usually learn a local denoising rule at each noise level, parameterized by a neural network that predicts one of the following equivalent quantities:

-

the injected Gaussian noise (\(\epsilon\)),

-

the original clean sample (\(x_0\)),

-

or the score (\(\nabla_x \log p_t(x)\)) of the noisy data distribution.

-

These parameterizations are mathematically interchangeable under Gaussian noise assumptions and correspond to different but equivalent views of the reverse diffusion dynamics. The equivalence between noise prediction and score matching provides the conceptual bridge between discrete-time DDPMs and continuous-time SGMs.

-

-

Mathematically speaking, in discrete-time diffusion models, the reverse model is typically trained via a denoising objective that matches the model’s prediction (most commonly \(\epsilon_\theta(x_t, t)\)) to the true Gaussian noise used to construct \(x_t\) from \(x_0\). Generation then emerges by repeatedly applying the learned update rule across discrete timesteps, starting from \(t = T\) and proceeding down to \(t = 0\).

- This discrete-time framing has proven remarkably robust, as it allows complex data distributions to be learned via simple Gaussian perturbations and local denoising steps rather than direct density modeling. Canonical examples of this class include Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) introduced in 2020, and their accelerated samplers such as Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIMs) introduced shortly thereafter in Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models by Song et al. (2020).

-

Continuous-time diffusion models generalize this perspective by describing the forward and reverse processes as SDEs defined over a continuous time variable (\(t \in [0,1]\)). In this formulation, diffusion is no longer tied to a fixed number of discrete noise levels but instead evolves according to continuous stochastic dynamics.

- Importantly, this continuous-time view is representation-agnostic: the same SDE framework applies whether diffusion is performed in pixel space, latent space, or another learned representation. Discrete-time diffusion models such as DDPMs and DDIMs can be recovered as specific numerical discretizations of these continuous-time processes, while earlier SGMs correspond to directly learning the score field required to solve the reverse-time SDE.

-

In practice, most large-scale systems rely on latent-space, discrete-time diffusion models trained with Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM)–style objectives, especially in image, video, and multimodal generation, due to their favorable trade-off between sample quality and computational cost. This design choice was popularized by Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs) in High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models by Rombach et al. (2022), which introduced diffusion in a learned latent space while retaining discrete-time training.

-

Sampling in modern systems is most commonly performed using DDIM–like deterministic or partially deterministic discrete-time samplers, or probability-flow ODE solvers derived from the continuous-time Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) framework.

-

By contrast, pure pixel-space discrete-time DDPMs and standalone continuous-time Score-Based Generative Models (SGMs) based on Langevin dynamics are now primarily used for research, benchmarking, or specialized domains where fidelity, theoretical clarity, or likelihood estimation is prioritized over raw sampling speed.

Discrete-Time Diffusion Models

-

Discrete-time diffusion models formulate generative modeling as a finite sequence of noising and denoising steps indexed by a timestep variable \(t \in {1,\dots,T}\). At each step, small amounts of Gaussian noise are added to data, and a neural network is trained to gradually remove this noise to recover clean samples.

-

This perspective originated in Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics by Sohl-Dickstein et al. (2015) and was popularized in its modern form by Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020).

-

From a taxonomy standpoint, discrete-time diffusion models occupy the time-discretized branch of the diffusion landscape and can be instantiated in different representation spaces:

- Pixel-space discrete-time diffusion models, where diffusion operates directly on raw data.

- Latent-space discrete-time diffusion models, where diffusion operates in a learned compressed representation.

-

Discrete-time diffusion models typically learn a local denoising rule at each noise level, parameterized by a neural network that predicts an equivalent quantity such as injected noise, the original clean sample, or the score of the noisy distribution.

-

Sampling proceeds by starting from pure Gaussian noise and repeatedly applying the learned denoising updates across timesteps. Although this yields high-quality samples, it can require many sequential steps.

-

Faster discrete-time sampling methods, such as Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIMs) introduced in Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models by Song et al. (2020), follow alternative deterministic or partially stochastic trajectories through the same discrete noise levels without changing training.

-

In modern practice, discrete-time diffusion models form the practical backbone of large-scale image, video, and multimodal generation systems, often combined with latent representations and accelerated samplers.

-

Having introduced discrete-time diffusion models along the time-formulation axis, we now turn to the representation-space axis and first examine pixel-space diffusion models, where the diffusion process operates directly on raw data such as image pixels or audio waveforms.

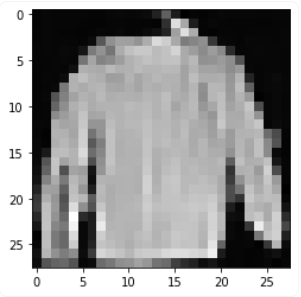

Pixel-Space Diffusion Models

-

Pixel-space diffusion models operate directly on high-dimensional data representations such as image pixels or raw audio waveforms. In this setting, the diffusion process acts on the original data coordinates, and no intermediate learned representation is introduced. As a result, pixel-space diffusion models offer a clear probabilistic interpretation and can achieve very high sample fidelity.

-

From a hierarchical perspective, pixel-space diffusion models can be further divided according to their time formulation:

- Discrete-time pixel-space diffusion models, where noise is added and removed over a finite sequence of timesteps.

-

Continuous-time pixel-space diffusion models, where diffusion is defined via SDEs and score matching.

- Historically and practically, discrete-time pixel-space diffusion models appeared first and form the conceptual foundation of the field.

-

While pixel-space diffusion enables precise modeling of fine-grained details, it also leads to substantial computational costs. The dimensionality of pixel data is extremely high, and both training and sampling require repeated neural network evaluations over many diffusion steps. These limitations motivated the development of latent-space diffusion models, which apply the same principles in a compressed representation.

-

Despite these costs, pixel-space diffusion models remain important for understanding the theoretical foundations of diffusion-based generative modeling and continue to be used in domains where the highest possible fidelity or exact likelihood computation is required.

Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs)

-

Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) are the canonical formulation of discrete-time diffusion-based generative modeling in pixel space. They were introduced in Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models by Ho et al. (2020) and define a tractable likelihood-based framework for learning complex data distributions via a sequence of noising and denoising steps indexed by a finite timestep variable.

-

In the hierarchy of diffusion models, DDPMs occupy a central position:

- They are discrete-time rather than continuous-time models.

- They operate directly in pixel space, rather than a learned latent space.

- They explicitly parameterize the reverse diffusion transitions as conditional probability distributions.

-

DDPMs model generation as the reversal of a fixed Markovian diffusion process that gradually destroys structure in the data by injecting Gaussian noise. Learning focuses on approximating the reverse transitions, which ultimately enables sampling from the data distribution starting from pure noise.

-

Overall, DDPMs form the conceptual backbone of modern diffusion models and serve as the starting point for numerous extensions, including accelerated discrete-time samplers (such as DDIMs), continuous-time SDE formulations, and latent-space diffusion models.

-

The Latent: Code the Maths offers a 3-part series covering the mathematical foundations of DDPMs, emphasizing intuition alongside derivations and lightweight code illustrations. Specifically, it offers a concise, math-first walkthrough of the theory behind DDPMs, starting from random variables and distributions, moving through Gaussian and multivariate Gaussian theory, and culminating in the forward/reverse diffusion processes, reparameterization, and training objectives.

Implementation Details

-

Forward (Diffusion / Noising) Process:

- The forward process is a fixed, non-learned Markov chain that progressively adds Gaussian noise to a data sample over \(T\) discrete timesteps. Given an original data point \(x_0\), the transition from timestep \(t-1\) to \(t\) is defined as:

-

where:

- \(q(x_t \mid x_{t-1})\) is the forward diffusion transition distribution from timestep \(t-1\) to \(t\).

- \(x_{t-1}\) is the noisy sample at timestep \(t-1\).

- \(x_t\) is the resulting noisy sample at timestep \(t\).

- \(N(\cdot ; \mu, \Sigma)\) denotes a multivariate Gaussian distribution with mean \(\mu\) and covariance \(\Sigma\).

- \(\beta_t\) is the variance of the Gaussian noise added at timestep \(t\).

- \({\beta_t}_{t=1}^T\) is a predefined variance schedule controlling the amount of noise added at each step.

- \(I\) is the identity covariance matrix.

- \(T\) is the total number of discrete diffusion steps.

-

As \(t\) increases, the signal-to-noise ratio decreases, and for sufficiently large \(T\), the distribution of \(x_T\) approaches a standard Gaussian.

-

A key property of this construction is that the marginal distribution \(q(x_t \mid x_0)\) admits a closed-form expression:

\[x_t = \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} x_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t}\epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim N(0, I)\]-

where:

- \(q(x_t \mid x_0)\) is the marginal distribution of the noisy sample at timestep \(t\) given the original data.

- \(x_0\) is the original clean data sample.

- \(x_t\) is the noisy version of the data at timestep \(t\).

- \(\epsilon\) is standard Gaussian noise.

- \(\epsilon \sim N(0, I)\) denotes sampling noise from a zero-mean unit-variance Gaussian.

- \(\alpha_t = 1 - \beta_t\) is the noise retention factor at timestep \(t\).

- \(\bar{\alpha}_t = \prod_{s=1}^t \alpha_s\) is the cumulative product of noise retention factors up to timestep \(t\).

-

This closed-form allows training to sample arbitrary timesteps directly without simulating the full forward chain.

-

-

Reverse (Denoising) Process:

-

The reverse process aims to invert the diffusion by learning a parameterized Markov chain that gradually removes noise. Each reverse transition is modeled as a Gaussian distribution:

\[p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t) = N\left(x_{t-1}; \mu_\theta(x_t, t), \sigma_t^2 I\right)\]-

where:

- \(p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\) is the learned reverse diffusion transition from timestep \(t\) to \(t-1\).

- \(x_t\) is the noisy sample at timestep \(t\).

- \(x_{t-1}\) is the denoised sample at timestep \(t-1\).

- \(N(\cdot;\mu,\Sigma)\) denotes a multivariate Gaussian distribution with mean \(\mu\) and covariance \(\Sigma\).

- \(\mu_\theta(x_t, t)\) is the predicted mean of the reverse transition, produced by a neural network with parameters \(\theta\) and conditioned on the timestep \(t\).

- \(\sigma_t^2\) is the variance of the reverse transition at timestep \(t\).

- \(I\) is the identity covariance matrix.

-

The mean is typically predicted by a U-Net conditioned on \(t\), while \(\sigma_t^2\) may be fixed or learned.

-

-

In practice, DDPMs are commonly parameterized to predict the noise \(\epsilon\) rather than the mean directly. This reparameterization simplifies optimization and improves empirical performance.

-

-

The following figure from the paper illustrates DDPMs as directed graphical models:

-

Training Objective:

- DDPMs are trained by maximizing a variational lower bound on the data log-likelihood. In practice, this objective simplifies to a denoising score-matching loss that minimizes the mean squared error between the true noise and the predicted noise:

-

where:

- \(L\) is the training loss.

- \(\mathbb{E}_{x_0, t, \epsilon}[\cdot]\) denotes expectation over data samples, timesteps, and noise.

- \(x_0\) is a clean data sample drawn from the training dataset.

- \(t\) is a timestep sampled uniformly from \({1,\ldots,T}\).

- \(\epsilon\) is Gaussian noise.

- \(\epsilon \sim N(0,I)\) denotes standard normal noise.

- \(x_t\) is the noisy version of \(x_0\) at timestep \(t\).

- \(\epsilon_\theta(x_t,t)\) is the neural network prediction of the noise contained in \(x_t\).

- \(\lVert \cdot \rVert^2\) denotes the squared Euclidean norm.

-

Sampling:

-

Sampling begins from pure Gaussian noise \(x_T \sim N(0, I)\) and applies the learned reverse transitions iteratively:

\[x_{t-1} \sim p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t), \quad t = T, \ldots, 1\]-

where:

- \(x_T \sim N(0,I)\) denotes initialization from standard Gaussian noise.

- \(p_\theta(x_{t-1} \mid x_t)\) is the learned reverse transition distribution.

- \(t = T,\ldots,1\) indicates that denoising proceeds backward in time from the noisiest state to the clean sample.

- \(x_0\) is the final generated sample after all denoising steps.

-

-

Each step incrementally denoises the sample until a final output \(x_0\) is produced. Although this procedure yields high-quality samples, it typically requires hundreds or thousands of sequential steps.

-

Pros

- Strong probabilistic foundation with an explicit likelihood formulation.

- Stable training and consistently high sample quality.

- Conceptually simple and broadly applicable across data modalities.

Cons

- Slow sampling due to the large number of required denoising steps.

- High computational cost for high-resolution data when operating in pixel space.

Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIMs)

-

Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIMs), are not separate classes of diffusion models but rather alternative sampling procedures applied to models trained with the DDPM objective. Introduced in Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models by Song et al. (2020), DDIMs replace the stochastic reverse Markov chain used in DDPM sampling with non-stochastic (i.e., deterministic) or partially stochastic trajectories that traverse the same discrete noise levels. This reinterpretation enables substantially faster generation without retraining, and places DDIMs within a broader family of discrete-time samplers that interpolate between fully stochastic DDPM sampling and deterministic probability-flow dynamics.

-

Within the time-formulation axis of the diffusion taxonomy, DDIMs should be understood as:

- operating in discrete time,

- reusing the same forward diffusion process and training objective as DDPMs,

- defining a deterministic or partially stochastic reverse process that follows a different trajectory through the same sequence of noise levels.

-

Conceptually, DDIMs demonstrate that the DDPM reverse process is only one member of a broader family of valid reverse processes consistent with the same forward diffusion. By selecting a deterministic member of this family, DDIMs enable substantially faster sampling without retraining the model.

-

DDIMs form a crucial conceptual and practical bridge between probabilistic discrete-time diffusion models and continuous-time probability-flow formulations derived from SDEs.

-