Primers • Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)

- Background: Pre-Training

- Enter BERT

- Word Embeddings

- Contextual vs. Non-contextual Word Embeddings

- BERT: An Overview

- What makes BERT different?

- Why Unsupervised Pre-Training?

- The Strength of Bidirectionality

- Masked Language Model (MLM)

- Next Sentence Prediction (NSP)

- Pre-training BERT

- Supervised Fine-Tuning

- Training with Cloud TPUs

- Results with BERT

- Making BERT Work for You

- A Visual Notebook to Using BERT for the First Time

- Limitations of Original BERT

- ModernBERT

- EuroBERT

- FAQs

- Further Reading

- References

- Citation

Background: Pre-Training

- One of the biggest challenges in natural language processing (NLP) is the shortage of training data. Because NLP is a diversified field with many distinct tasks, most task-specific datasets contain only a few thousand or a few hundred thousand human-labeled training examples. However, modern deep learning-based NLP models see benefits from much larger amounts of data, improving when trained on millions, or billions, of annotated training examples. To help close this gap in data, researchers have developed a variety of techniques for training general purpose language representation models using the enormous amount of unannotated text on the web (known as pre-training).

- The pre-trained model can then be fine-tuned on small-data NLP tasks like question answering and sentiment analysis, resulting in substantial accuracy improvements compared to training on these datasets from scratch.

Enter BERT

- In 2018, Google open sourced a new technique for NLP pre-training called Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers, or BERT. As the name suggests, it generates representations using an encoder from Vaswani et al.’s Transformer architecture. However, there are notable differences between BERT and the original Transformer, especially in how they train those models.

- With BERT, anyone in the world can train their own state-of-the-art question answering system (or a variety of other models) in about 30 minutes on a single Cloud TPU, or in a few hours using a single GPU. The release includes source code built on top of TensorFlow and a number of pre-trained language representation models.

- In the paper, Devlin et al. (2018) demonstrate state-of-the-art results on 11 NLP tasks, including the very competitive Stanford Question Answering Dataset (SQuAD v1.1).

Word Embeddings

- Word embeddings (or word vectors) are a way to represent words or sentences as vectors of numbers that can be fed into downstream models for various tasks such as search, recommendation, translation and so on. The idea can be generalized to various entities beyond words – for e.g., topics, products, and even people (commonly done in applications such as recommender systems, face/speaker recognition, etc.).

- Word2Vec has been one of the most commonly used models that popularized the use of embeddings and made them accessible through easy to use pre-trained embeddings (in case of Word2Vec, pre-trained embeddings trained on the Google News corpus are available). Two important learnings from Word2Vec were:

- Embeddings of semantically similar words are close in cosine similarity.

- Word embeddings support intuitive arithmetic properties. (An important consequence of this statement is that phrase embeddings can be obtained as the sum of word embeddings.)

- However, since Word2Vec there have been numerous techniques that attempted to create better and better deep learning models for producing embeddings (as we’ll see in the later sections).

Contextual vs. Non-contextual Word Embeddings

- It is often stated that Word2Vec and GloVe yield non-contextual embeddings while ELMo and BERT embeddings are contextual. At a top level, all word embeddings are fundamentally non-contextual but can be made contextual by incorporating hidden layers:

- The word2vec model is trained to learn embeddings that predict either the probability of a surrounding word occurring given a center word (SkipGram) or vice versa (CBoW). The surrounding words are also called context words because they appear in the context of the center word.

- The GloVe model is trained such that a pair of embeddings has weights that reflect their co-occurrence probability. The latter is defined as the percentage of times that a given word \(y\) occurs within some context window of word \(x\).

- If embeddings are trained from scratch in an encoder / decoder framework involving RNNs (or their variants), then, at the input layer, the embedding that you look up for a given word reflects nothing about the context of the word in that particular sentence. The same goes for Transformer-based architectures.

- Word2Vec and GloVe embeddings can be plugged into any type of neural language model, and contextual embeddings can be derived from them by incorporating hidden layers. These layers extract the meaning of a given word, accounting for the words it is surrounded by (i.e., the context) in that particular sentence. Similarly, while hidden layers of an LSTM encoder or Transformer do extract information about surrounding words to represent a given word, the embeddings at the input layer do not.

- Key takeaways

- Word embeddings you retrieve from a lookup table are always non-contextual since you cannot have pre-generated contextualized embeddings. (It is slightly different in ELMo which uses a character-based network to get a word embedding, but it does consider context).

- However, when people say contextual word embeddings, they don’t mean the vectors from the look-up table, they mean the hidden states of the pre-trained model.

- Here are the key differences between them Word2Vec and BERT embeddings and when to use each:

| BERT | Word2Vec | |

|---|---|---|

| Central idea | Offers different embeddings based on context, i.e., "contextual embeddings" (say, the game "Go" vs. the verb "go"). The same word occurs in different contexts can thus yield different embeddings. | Same embedding for a given word even if it occurs in different contexts. |

| Context/Dependency coverage | Captures longer range context/dependencies owing to the Transformer encoder architecture under-the-hood which is designed to capture more context. | While Word2Vec Skipgram tries to predict contextual (surrounding) words based on the center word (and CBOW does the reverse, i.e., ), both are limited in their context to just a static window size (which is a hyperparameter) and thus cannot capture longer range context relative to BERT. |

| Position sensitivity | Takes into account word position since it uses positional embeddings at the input. | Does not take into account word position and is thus word-position agnostic (hence, called "bag of words" which indicates it is insensitive to word position). |

| Generating embeddings | Use a pre-trained model and generate embeddings for desired words (rather than using pre-trained embeddings as in Word2Vec) since they are tailor-fit based on the context. | Off-the-shelf pre-trained word embeddings available since embeddings are context-agnostic. |

ELMo: Contextualized Embeddings

- ELMo came up with the concept of contextualized embeddings by grouping together the hidden states of the LSTM-based model (and the initial non-contextualized embedding) in a certain way (concatenation followed by weighted summation).

BERT: An Overview

- At the input, BERT (and many other transformer models) consume 512 tokens max —- truncating anything beyond this length. Since it can generate an output per input token, it can output 512 tokens.

- BERT actually uses WordPieces as tokens rather than the input words – so some words are broken down into smaller chunks.

- BERT is trained using two objectives: (i) Masked Language Modeling (MLM), and (ii) Next Sentence Prediction (NSP).

Masked Language Modeling (MLM)

- While the OpenAI transformer (which was a decoder) gave us a fine-tunable (through prompting) pre-trained model based on the Transformer, something went missing in this transition from LSTMs (ELMo) to Transformers (OpenAI Transformer). ELMo’s language model was bi-directional, but the OpenAI transformer is a forward language model. Could we build a transformer-based model whose language model looks both forward and backwards (in the technical jargon – “is conditioned on both left and right context”)?

- However, here’s the issue with bidirectional conditioning when pre-training a language model. The community usually trains a language model by training it on a related task which helps develop a contextual understanding of words in a model. More often than not, such tasks involve predicting the next word or words in close vicinity of each other. Such training methods can’t be extended and used for bidirectional models because it would allow each word to indirectly “see itself” — when you would approach the same sentence again but from opposite direction, you kind of already know what to expect. A case of data leakage. In other words, bidrectional conditioning would allow each word to indirectly see itself in a multi-layered context. The training objective of Masked Language Modelling, which seeks to predict the masked tokens, solves this problem.

- While the masked language modelling objective allows us to obtain a bidirectional pre-trained model, note that a downside is that we are creating a mismatch between pre-training and fine-tuning, since the

[MASK]token does not appear during fine-tuning. To mitigate this, BERT does not always replace “masked” words with the actual[MASK]token. The training data generator chooses 15% of the token positions at random for prediction. If the \(i^{th}\) token is chosen, BERT replaces the \(i^{th}\) token with (1) the[MASK]token 80% of the time (2) a random token 10% of the time, and (3) the unchanged \(i^{th}\) token 10% of the time.

Next Sentence Prediction (NSP)

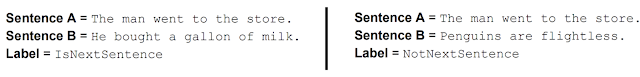

- To make BERT better at handling relationships between multiple sentences, the pre-training process includes an additional task: Given two sentences (\(A\) and \(B\)), is \(B\) likely to be the sentence that follows \(A\), or not?

- More on the two pre-training objectives in the section on Masked Language Model (MLM) and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP).

BERT Flavors

- BERT comes in two flavors:

- BERT Base: 12 layers (transformer blocks), 12 attention heads, 768 hidden size (i.e., the size of \(q\), \(k\) and \(v\) vectors), and 110 million parameters.

- BERT Large: 24 layers (transformer blocks), 16 attention heads, 1024 hidden size (i.e., the size of \(q\), \(k\) and \(v\) vectors) and 340 million parameters.

- By default BERT (which typically refers to BERT-base), word embeddings have 768 dimensions.

Sentence Embeddings with BERT

- To calculate sentence embeddings using BERT, there are multiple strategies, but a simple approach is to average the second to last hidden layer of each token producing a single 768 length vector. You can also do a weighted sum of the vectors of words in the sentence.

BERT’s Encoder Architecture vs. Other Decoder Architectures

- BERT is based on the Transformer encoder. Unlike BERT, decoder models (GPT, TransformerXL, XLNet, etc.) are auto-regressive in nature. As an encoder-based architecture, BERT traded-off auto-regression and gained the ability to incorporate context on both sides of a word and thereby offer better results.

- Note that XLNet brings back autoregression while finding an alternative way to incorporate the context on both sides.

- More on this in the article on Encoding vs. Decoder Models.

What makes BERT different?

- BERT builds upon recent work in pre-training contextual representations — including Semi-supervised Sequence Learning, Generative Pre-Training, ELMo, and ULMFit.

- However, unlike these previous models, BERT is the first deeply bidirectional, unsupervised language representation, pre-trained using only a plain text corpus (in this case, Wikipedia).

- Why does this matter? Pre-trained representations can either be context-free or contextual, and contextual representations can further be unidirectional or bidirectional. Context-free models such as word2vec or GloVe generate a single word embedding representation for each word in the vocabulary.

- For example, the word “bank” would have the same context-free representation in “bank account” and “bank of the river.” Contextual models instead generate a representation of each word that is based on the other words in the sentence. For example, in the sentence “I accessed the bank account,” a unidirectional contextual model would represent “bank” based on “I accessed the” but not “account.” However, BERT represents “bank” using both its previous and next context — “I accessed the … account” — starting from the very bottom of a deep neural network, making it deeply bidirectional.

- A visualization of BERT’s neural network architecture compared to previous state-of-the-art contextual pre-training methods is shown below (source). BERT is deeply bidirectional, OpenAI GPT is unidirectional, and ELMo is shallowly bidirectional. The arrows indicate the information flow from one layer to the next. The green boxes at the top indicate the final contextualized representation of each input word:

Why Unsupervised Pre-Training?

- Vaswani et al. employed supervised learning to train the original Transformer models for language translation tasks, which requires pairs of source and target language sentences. For example, a German-to-English translation model needs a training dataset with many German sentences and corresponding English translations. Collecting such text data may involve much work, but we require them to ensure machine translation quality. There is not much else we can do about it, or can we?

- We actually can use unsupervised learning to tap into many unlabelled corpora. However, before discussing unsupervised learning, let’s look at another problem with supervised representation learning. The original Transformer architecture has an encoder for a source language and a decoder for a target language. The encoder learns task-specific representations, which are helpful for the decoder to perform translation, i.e., from German sentences to English. It sounds reasonable that the model learns representations helpful for the ultimate objective. But there is a catch.

- If we wanted the model to perform other tasks like question answering and language inference, we would need to modify its architecture and re-train it from scratch. It is time-consuming, especially with a large corpus.

- Would human brains learn different representations for each specific task? It does not seem so. When kids learn a language, they do not aim for a single task in mind. They would somehow understand the use of words in many situations and acquire how to adjust and apply them for multiple activities.

- To summarize what we have discussed so far, the question is whether we can train a model with many unlabeled texts to generate representations and adjust the model for different tasks without from-scratch training.

- The answer is a resounding yes, and that’s exactly what Devlin et al. did with BERT. They pre-trained a model with unsupervised learning to obtain non-task-specific representations helpful for various language model tasks. Then, they added one additional output layer to fine-tune the pre-trained model for each task, achieving state-of-the-art results on eleven natural language processing tasks like GLUE, MultiNLI, and SQuAD v1.1 and v2.0 (question answering).

- So, the first step in the BERT framework is to pre-train a model on a large amount of unlabeled data, giving many contexts for the model to learn representations in unsupervised training. The resulting pre-trained BERT model is a non-task-specific feature extractor that we can fine-tune quickly to a specific objective.

- The next question is how they pre-trained BERT using text datasets without labeling.

The Strength of Bidirectionality

- If bidirectionality is so powerful, why hasn’t it been done before? To understand why, consider that unidirectional models are efficiently trained by predicting each word conditioned on the previous words in the sentence. However, it is not possible to train bidirectional models by simply conditioning each word on its previous and next words, since this would allow the word that’s being predicted to indirectly “see itself” in a multi-layer model.

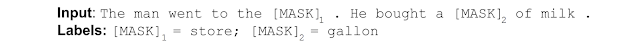

- To solve this problem, BERT uses the straightforward technique of masking out some of the words in the input and then condition each word bidirectionally to predict the masked words. In other words, BERT uses the neighboring words (i.e., bidirectional context) to predict the current masked word – also known as the Cloze task. For example (image source):

- While this idea has been around for a very long time, BERT was the first to adopt it to pre-train a deep neural network.

- BERT also learns to model relationships between sentences by pre-training on a very simple task that can be generated from any text corpus: given two sentences \(A\) and \(B\), is \(B\) the actual next sentence that comes after \(A\) in the corpus, or just a random sentence? For example (image source):

- Thus, BERT has been trained on two main tasks:

- Masked Language Model (MLM)

- Next Sentence Prediction (NSP)

Masked Language Model (MLM)

- Language models (LM) estimate the probability of the next word following a sequence of words in a sentence. One application of LM is to generate texts given a prompt by predicting the most probable word sequence. It is a left-to-right language model.

- Note: “left-to-right” may imply languages such as English and German. However, other languages use “right-to-left” or “top-to-bottom” sequences. Therefore, “left-to-right” means the natural flow of language sequences (forward), not aiming for specific languages. Also, “right-to-left” means the reverse order of language sequences (backward).

- Unlike left-to-right language models, the masked language models (MLM) estimate the probability of masked words. We randomly hide (mask) some tokens from the input and ask the model to predict the original tokens in the masked positions. It lets us use unlabeled text data since we hide tokens that become labels (as such, we may call it “self-supervised” rather than “unsupervised,” but I’ll keep the same terminology as the paper for consistency’s sake).

- The model predicts each hidden token solely based on its context, where the self-attention mechanism from the Transformer architecture comes into play. The context of a hidden token originates from both directions since the self-attention mechanism considers all tokens, not just the ones preceding the hidden token. Devlin et al. call such representation bi-directional, comparing with uni-directional representation by left-to-right language models.

- Note: the term “bi-directional” is a bit misnomer because the self-attention mechanism is not directional at all. However, we should treat the term as the antithesis of “uni-directional”.

- In the paper, they have a footnote (4) that says:

We note that in the literature the bidirectional Transformer is often referred to as a “Transformer encoder” while the left-context-only unidirectional version is referred to as a “Transformer decoder” since it can be used for text generation.

- So, Devlin et al. trained an encoder (including the self-attention layers) to generate bi-directional representations, which can be richer than uni-directional representations from left-to-right language models for some tasks. Also, it is better than simply concatenating independently trained left-to-right and right-to-left language model representations because bi-directional representations simultaneously incorporate contexts from all tokens.

- However, many tasks involve understanding the relationship between two sentences, such as Question Answering (QA) and Natural Language Inference (NLI). Language modeling (LM or MLM) does not capture this information.

- We need another unsupervised representation learning task for multi-sentence relationships.

Next Sentence Prediction (NSP)

- A next sentence prediction is a task to predict a binary value (i.e., Yes/No, True/False) to learn the relationship between two sentences. For example, there are two sentences \(A\) and \(B\), and the model predicts if \(B\) is the actual next sentence that follows \(A\). They randomly used the true or false next sentence for \(B\). It is easy to generate such a dataset from any monolingual corpus. Hence, it is unsupervised learning.

Pre-training BERT

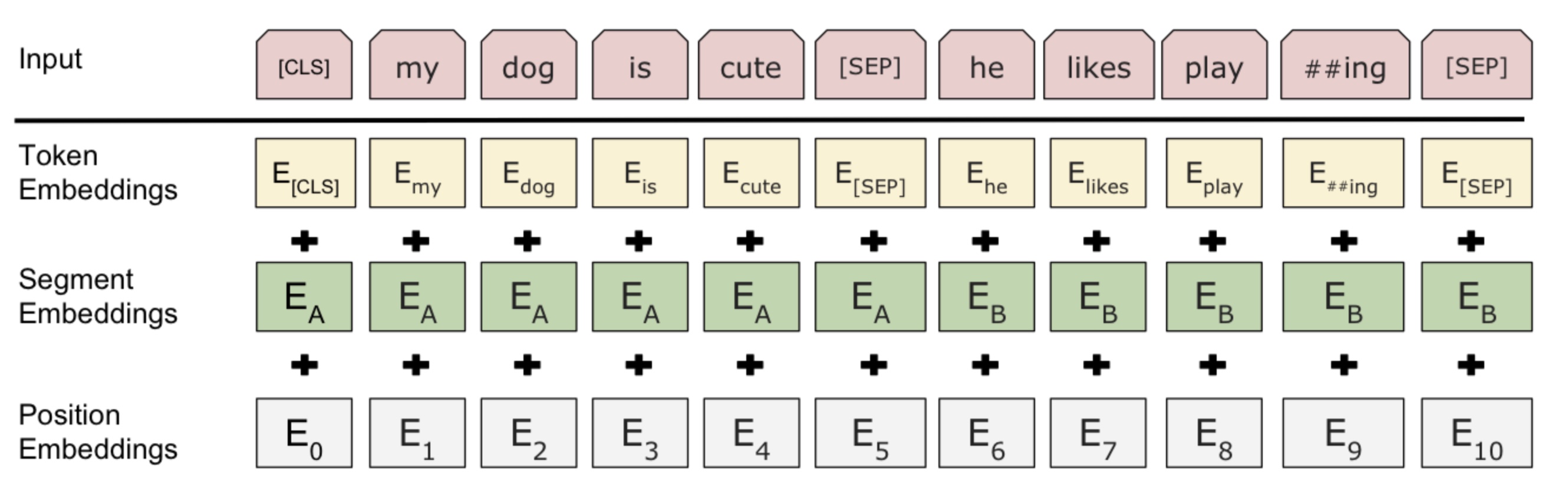

- How can we pre-train a model for both MLM and NSP tasks? To understand how a model can accommodate two pre-training objectives, let’s look at how they tokenize inputs.

- They used WordPiece for tokenization, which has a vocabulary of 30,000 tokens, based on the most frequent sub-words (combinations of characters and symbols). Special tokens such as

[CLS](Classification Token),SEP(Separator Token), andMASK(Masked Token) are added during the tokenization process. These tokens are added to the input sequences during the pre-processing stage, both for training and inference. Let’s delve into these special tokens one-by-one: [CLS](Classification Token):- The CLS token, short for “Classification Token,” is a special token used in BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) and similar models. Its primary purpose is to represent the entire input sequence when BERT is used for various NLP (Natural Language Processing) tasks. Here are key points about the CLS token:

- Representation of the Whole Sequence: The CLS token is placed at the beginning of the input sequence and serves as a representation of the entire sequence. It encapsulates the contextual information from all the tokens in the input.

- Classification Task: In downstream NLP tasks like text classification or sentiment analysis, BERT’s final hidden state corresponding to the CLS token is often used as the input to a classifier to make predictions.

- Position and Usage: The CLS token is added to the input during the pre-processing stage before training or inference. It’s inserted at the beginning of the tokenized input, and BERT’s architecture ensures that it captures contextual information from all tokens in both left and right directions.

- The CLS token, short for “Classification Token,” is a special token used in BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) and similar models. Its primary purpose is to represent the entire input sequence when BERT is used for various NLP (Natural Language Processing) tasks. Here are key points about the CLS token:

[SEP](Separator Token):- The SEP token, short for “Separator Token,” is another special token used in BERT. Its primary role is to separate segments or sentences within an input sequence. Here’s what you need to know about the SEP token:

- Segment Separation: The SEP token is inserted between segments or sentences in the input sequence. It helps BERT distinguish between different parts of the input, especially when multiple sentences are concatenated for training or inference.

- Position and Usage: Like the CLS token, the SEP token is added during the pre-processing stage. It’s placed between segments, ensuring that BERT understands the boundaries between different sentences.

- Example: In a question-answering task, where a question and a passage are combined as input, the SEP token is used to indicate the boundary between the question and the passage.

- The SEP token, short for “Separator Token,” is another special token used in BERT. Its primary role is to separate segments or sentences within an input sequence. Here’s what you need to know about the SEP token:

[MASK](Masked Token):- The MASK token is used during the pre-training phase of BERT, which involves masking certain tokens in the input for the model to predict. Here’s what you should know about the MASK token:

- Masked Tokens for Pre-training: During pre-training, some of the tokens in the input sequence are randomly selected to be replaced with the MASK token. The model’s objective is to predict the original identity of these masked tokens.

- Training Objective: The MASK token is introduced during the training phase to improve BERT’s ability to understand context and relationships between words. The model learns to predict the masked tokens based on the surrounding context.

- Position and Usage: The MASK token is applied to tokens before feeding them into the model during the pre-training stage. This masking process is part of the unsupervised pre-training of BERT.

- The MASK token is used during the pre-training phase of BERT, which involves masking certain tokens in the input for the model to predict. Here’s what you should know about the MASK token:

- In summary, the CLS token , the SEP token , and the MASK token is , enhancing BERT’s contextual understanding.

[CLS]: Stands for classification and is the first token of every sequence. The final hidden state is the aggregate sequence representation. It thus represents the entire input sequence and is used for classification tasks.[SEP]: A separator token for separating segments within the input, such as sentences, questions, and related passages.[MASK]: Used to mask/hide tokens.

- For the MLM task, they randomly choose a token to replace with the

[MASK]token. They calculate cross-entropy loss between the model’s prediction and the masked token to train the model. Specific details about this masking procedure are as follows:- To train a deep bidirectional representation, the researchers mask a certain percentage of the input tokens randomly and then predict those masked tokens. This procedure is known as a “masked LM” (MLM), also commonly referred to as a Cloze task in academic literature. The final hidden vectors corresponding to the mask tokens are fed into an output softmax over the vocabulary, similar to a standard LM. In their experiments, 15% of all WordPiece tokens in each sequence are masked randomly. This approach differs from denoising auto-encoders, as only the masked words are predicted, not the entire input reconstruction.

- While this method enables the creation of a bidirectional pre-trained model, it introduces a mismatch between pre-training and fine-tuning phases due to the absence of the

[MASK]token during fine-tuning. To address this, the masked words are not always replaced with the actual[MASK]token. The training data generator randomly selects 15% of the token positions for prediction. If the \(i^{th}\) token is chosen, it is replaced with the[MASK]token 80% of the time, a random token 10% of the time, or remains unchanged 10% of the time. The goal is to use \(T_i\) to predict the original token with cross-entropy loss.

- For the NSP task, given sentences \(A\) and \(B\), the model learns to predict if \(B\) follows \(A\). They separated sentences \(A\) and \(B\) using

[SEP]token and used the final hidden state in place of[CLS]for binary classification. The output of the[CLS]token tells us how likely the current sentence follows the prior sentence. You can think about the output of[CLS]as a probability. The motivation is that the [CLS]embedding should contain a “summary” of both sentences to be able to decide if they follow each other or not. Note that they can’t take any other word from the input sequence, because the output of the word is it’s representation. So they add a tag that has no other purpose than being a sentence-level representation for classification. Their final model achieved 97%-98% accuracy on this task. - Now you may ask the question – instead of using

[CLS]’s output, can we just output a number as probability? Yes, we can do that if the task of predicting next sentence is a separate task. However, BERT has been trained on both the MLM and NSP tasks simultaneously. Organizing inputs and outputs in such a format (with both[MASK]and[CLS]) helps BERT to learn both tasks at the same time and boost its performance. - When it comes to classification task (e.g. sentiment classification), the output of [CLS] can be helpful because it contains BERT’s understanding at the sentence-level.

- Note: there is one more detail when separating two sentences. They added a learned “segment” embedding to every token, indicating whether it belongs to sentence \(A\) or \(B\). It’s similar to positional encoding, but it is for sentence level. They call it segmentation embeddings. Figure 2 of the paper shows the various embeddings corresponding to the input.

- So, Devlin et al. pre-trained BERT using the two unsupervised tasks and empirically showed that pre-trained bi-directional representations could help execute various language tasks involving single text or text pairs.

- The final step is to conduct supervised fine-tuning to perform specific tasks.

Supervised Fine-Tuning

- Fine-tuning adjusts all pre-trained model parameters for a specific task, which is a lot faster than from-scratch training. Furthermore, it is more flexible than feature-based training that fixes pre-trained parameters. As a result, we can quickly train a model for each specific task without heavily engineering a task-specific architecture.

- The pre-trained BERT model can generate representations for single text or text pairs, thanks to the special tokens and the two unsupervised language modeling pre-training tasks. As such, we can plug task-specific inputs and outputs into BERT for each downstream task.

- For classification tasks, we feed the final

[CLS]representation to an output layer. For multi-sentence tasks, the encoder can process a concatenated text pair (using[SEP]) into bi-directional cross attention between two sentences. For example, we can use it for question-passage pair in a question-answering task. - By now, it should be clear why and how they repurposed the Transformer architecture, especially the self-attention mechanism through unsupervised pre-training objectives and downstream task-specific fine-tuning.

Training with Cloud TPUs

- Everything that we’ve described so far might seem fairly straightforward, so what’s the missing piece that made it work so well? Cloud TPUs. Cloud TPUs gave us the freedom to quickly experiment, debug, and tweak our models, which was critical in allowing us to move beyond existing pre-training techniques.

- The Transformer model architecture, developed by researchers at Google in 2017, gave BERT the foundation to make it successful. The Transformer is implemented in Google’s open source release, as well as the tensor2tensor library.

Results with BERT

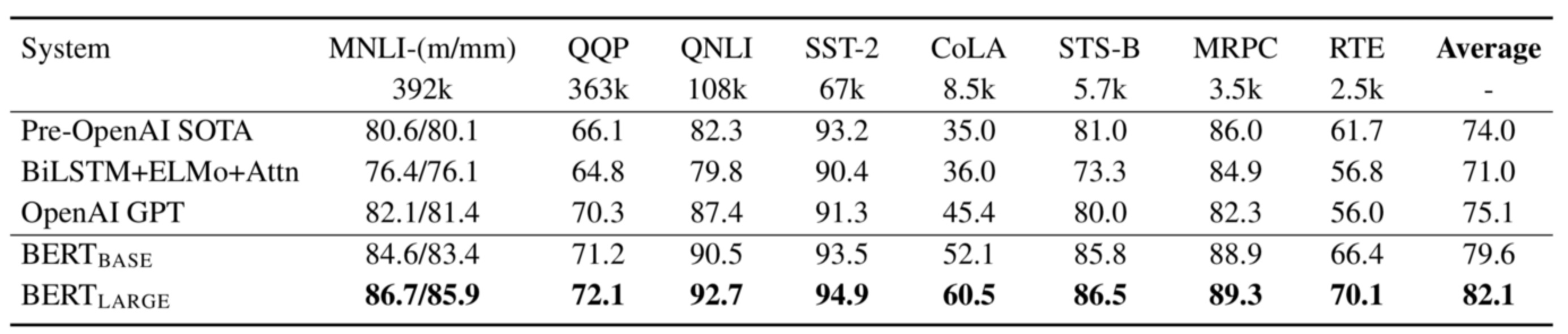

- To evaluate performance, we compared BERT to other state-of-the-art NLP systems. Importantly, BERT achieved all of its results with almost no task-specific changes to the neural network architecture.

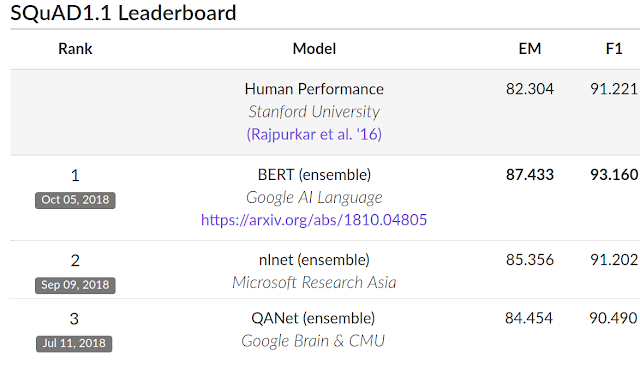

- On SQuAD v1.1, BERT achieves 93.2% F1 score (a measure of accuracy), surpassing the previous state-of-the-art score of 91.6% and human-level score of 91.2%:

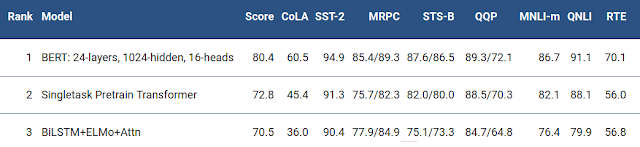

- BERT also improves the state-of-the-art by 7.6% absolute on the very challenging GLUE benchmark, a set of 9 diverse Natural Language Understanding (NLU) tasks. The amount of human-labeled training data in these tasks ranges from 2,500 examples to 400,000 examples, and BERT substantially improves upon the state-of-the-art accuracy on all of them:

- Below are the GLUE test results from table 1 of the paper. They reported results on the two model sizes:

- The base BERT uses 110M parameters in total:

- 12 encoder blocks

- 768-dimensional embedding vectors

- 12 attention heads

- The large BERT uses 340M parameters in total:

- 24 encoder blocks

- 1024-dimensional embedding vectors

- 16 attention heads

- The base BERT uses 110M parameters in total:

Google search improvements

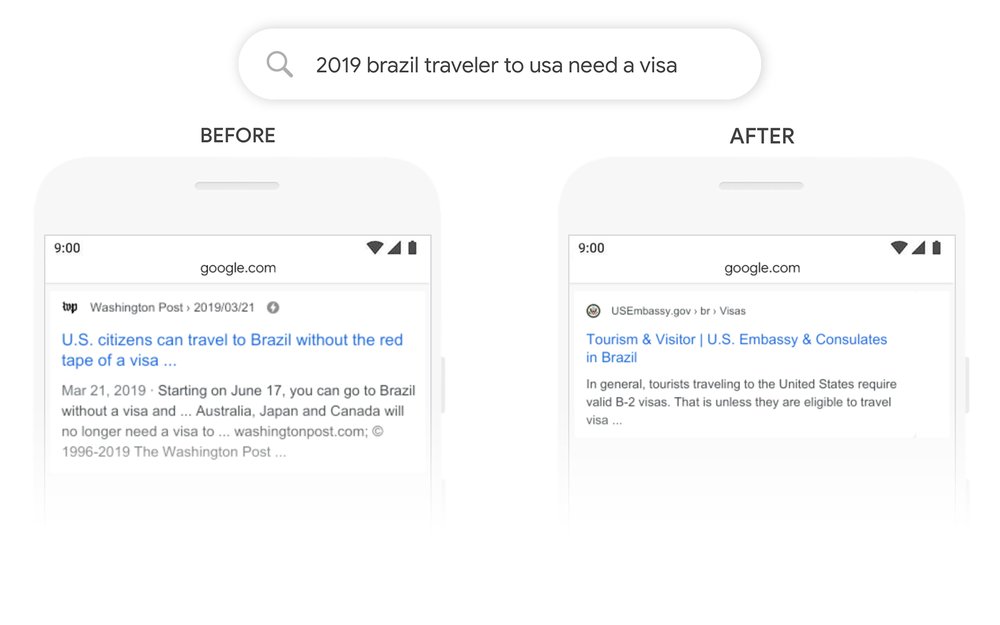

- Google search deployed BERT for understanding search queries in 2019.

- Given an input query, say “2019 brazil traveler to usa need a visa”, the following image shows the difference in Google’s search results before and after BERT. Based on the image, we can see that BERT (“after”) does a much better job at understanding the query compared to the keyword-based match (before). A keyword-based match yields articles related to US citizens traveling to Brazil whereas the intent behind the query was someone in Brazil looking to travel to the USA.

Making BERT Work for You

- The models that Google has released can be fine-tuned on a wide variety of NLP tasks in a few hours or less. The open source release also includes code to run pre-training, although we believe the majority of NLP researchers who use BERT will never need to pre-train their own models from scratch. The BERT models that Google has released so far are English-only, but they are working on releasing models which have been pre-trained on a variety of languages in the near future.

- The open source TensorFlow implementation and pointers to pre-trained BERT models can be found here. Alternatively, you can get started using BERT through Colab with the notebook “BERT FineTuning with Cloud TPUs”.

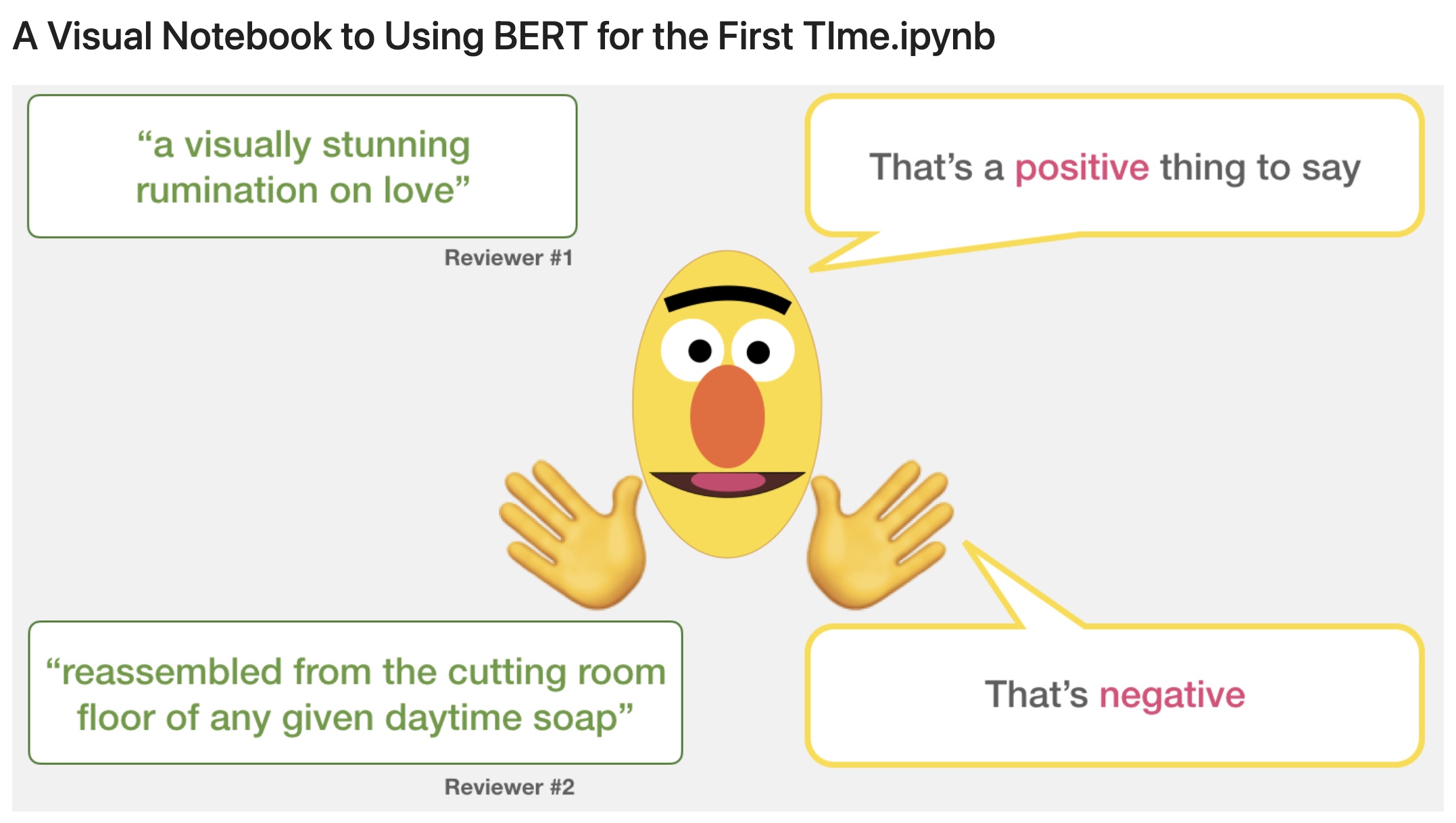

A Visual Notebook to Using BERT for the First Time

- This Jupyter notebook by Jay Alammar offers a great intro to using a pre-trained BERT model to carry out sentiment classification using the Stanford Sentiment Treebank (SST2) dataset.

Limitations of Original BERT

-

Despite its significance, the original BERT has several key limitations that motivated the research of improved models:

-

Computational Inefficiency and Long-Range Limits: BERT’s Transformer uses full self-attention across all tokens in each layer, which scales quadratically with sequence length. This made the max input length 512 tokens for feasibility, restricting BERT from handling longer documents. Training BERT was resource-intensive: the base model pre-training took 4 days on 16 TPU chips (and BERT-Large took 4 days on 64 TPUs). Such high compute requirements and memory usage make it costly to scale BERT or apply it to long texts. Inference can also be slow on edge devices due to the model’s size and dense computation.

-

Lack of Adaptability to Diverse Languages: The original BERT was trained on English (with a separate model for Chinese). A multilingual BERT (mBERT) was released covering 104 languages, but it was trained on relatively limited Wikipedia data for each language, all within a 110M parameter model. As a result, its representations for low-resource languages were suboptimal. Subsequent studies showed that models trained on larger multilingual corpora can far outperform mBERT. BERT’s architecture and training needed scaling to handle multiple languages effectively; without that, users resorted to separate monolingual models or saw degraded performance on non-English tasks.

-

Model Size and Efficiency Constraints: BERT-base and BERT-large were relatively large for 2018 standards. BERT-large (340M) yields better accuracy than base, but is cumbersome to deploy and fine-tune. Its size and memory footprint can be prohibitively slow for users with limited resources. This led to efforts like DistilBERT (66M params) which distills BERT to a smaller model with ~97% of its performance but ~60% faster inference. The need for such compressed models highlighted that BERT’s original parameterization wasn’t optimally efficient. Moreover, BERT’s use of fully learned positional embeddings tied to a 512 length means it cannot naturally generalize to longer sequences without retraining or imaginative hacks. In summary, original BERT had a trade-off between performance and practicality: it was not designed for extreme efficiency, cross-lingual flexibility, or handling specialized domains (like code or math) out-of-the-box. These limitations set the stage for ModernBERT and EuroBERT.

-

ModernBERT

- ModernBERT is an encoder-only model, released in late 2024, designed as a drop-in upgrade to BERT that addresses many of BERT’s weaknesses. It brings BERT’s architecture up to date with the last few years of Transformer research, achieving major improvements in both downstream performance and efficiency. Below, we discuss ModernBERT’s architectural changes, training methodology, and the resulting performance gains in detail.

Architectural Changes in ModernBERT

-

ModernBERT’s architecture introduces multiple innovations while still being an encoder-only Transformer like BERT. The key changes include:

-

Deeper but Narrower Transformer: ModernBERT uses more Transformer layers than BERT for greater representational power, but makes each layer “thinner” to control the parameter count. For example, ModernBERT-large has 28 layers (vs 24 in BERT-large) but a reduced feed-forward hidden size (e.g. ~2624 instead of 4096) to keep the model ~400M params. Empirical studies have shown that at equal parameter counts, increasing depth while reducing width yields better downstream performance (the model captures higher-level abstractions). This “deep-and-thin” design gives ModernBERT strong accuracy without a parameter explosion.

-

Removal of Redundant Biases: Following efficient Transformer design insights, ModernBERT eliminates most bias terms in the network. All linear layers except the final output projection have no bias, and LayerNorm layers have no bias as well. Removing these unnecessary parameters slightly shrinks the model and, more importantly, reallocates capacity to the weights that matter (the linear transformations). This helps ModernBERT use its parameter budget more effectively. The only bias retained is in the final decoder layer, which the authors hypothesized might mitigate any small degradation from weight tying.

-

Pre-Normalization and Additional LayerNorm: BERT used post-layer normalization, whereas ModernBERT adopts a pre-normalization architecture (LayerNorm applied before the attention and FF sublayers). Pre-norm transformers are known to stabilize training for deep models. ModernBERT also adds an extra LayerNorm after the word embedding layer (and correspondingly removes the first LayerNorm in the first Transformer block to avoid duplication). This ensures the input to the first attention layer is normalized, improving training stability for the deep network. These tweaks address training instabilities that original BERT could face when scaled up.

-

GeGLU Activation in Feed-Forward Layers: ModernBERT replaces BERT’s Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation in the feed-forward layers with Gated GeLU (GeGLU). GeGLU is a gated linear unit variant where one half of the layer’s hidden units are used to gate the other half (multiplicatively) before applying GeLU. Formally, if \(h = \text{Linear}_1(x)\) and \(g = \text{Linear}_2(x)\), then output = \(\text{GeLU}(g) \otimes h\) (elementwise product). This has been shown to consistently improve model quality in Transformers. By using GeGLU, ModernBERT’s feed-forward networks can learn more expressive transformations than a standard two-layer MLP, boosting performance on language understanding tasks.

-

Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE): Instead of the fixed positional embeddings used in BERT, ModernBERT employs RoPE to represent token positions. RoPE imparts positional information by rotating query/key vectors in multi-head attention as a function of their position index, allowing extrapolation to longer sequences than seen in training. RoPE has proven effective in both short- and long-context language models. By using RoPE, ModernBERT can natively handle sequences up to 8,192 tokens – a 16× increase in context length over BERT’s 512. Importantly, RoPE makes it easier to extend context length without retraining (no learned position embeddings tied to a fixed size). This change equips ModernBERT for document-length inputs and long-range reasoning tasks.

-

Alternating Global/Local Attention: A major innovation in ModernBERT is its alternating attention pattern across layers. Instead of full self-attention in every layer, ModernBERT layers alternate between global attention (full sequence attention) and local attention (attention within a sliding window of 128 tokens). Concretely, in ModernBERT every third layer is a global attention layer (to propagate information across the whole sequence), while the other layers use local windowed attention (each token attends only to neighbors within 128 tokens). This drastically reduces the computation for long sequences – local attention is O(n · w) rather than O(n²) (with window size w = 128). The model still periodically mixes global context (every third layer) to maintain long-range coherence. This design was inspired by efficient long-form Transformers like BigBird/Longformer. In ModernBERT, global layers even apply RoPE with a larger rotation period (theta = 160k) to effectively handle very long distances. The alternating pattern strikes a balance between coverage of long-range dependencies and computational efficiency, enabling 8192-length processing with manageable cost.

-

Unpadding and Sparse Computation: ModernBERT incorporates an “unpadding” technique to eliminate wasted computation on padding tokens. In BERT and similar models, batching sentences of different lengths results in padding tokens to align lengths, which consume compute but carry no information. ModernBERT instead concatenates all sequences in a batch into one long sequence (after embedding) and processes it as one batch with a jagged attention mask to separate the original sequences. Thanks to support from FlashAttention’s variable-length kernels, it can do this without re-padding between layers. This yields a 10–20% throughput improvement just by avoiding pads. Combined with the use of FlashAttention (an optimized attention algorithm that computes attention in tiled blocks to avoid memory blow-up), ModernBERT maximizes speed and memory efficiency. In practice, ModernBERT uses FlashAttention v3 for global attention layers and v2 for local layers (because at the time, v3 didn’t support local windows). These low-level optimizations ensure that ModernBERT’s theoretical efficiency gains translate to real speedups on hardware.

-

Hardware-Aware Design: Unusually, ModernBERT was co-designed with hardware constraints in mind. The developers performed many small-scale ablations to choose dimensions and layer sizes that maximize utilization of common GPUs (like NVIDIA T4, RTX 3090, etc.). For example, they set the vocabulary size to 50,368 – a multiple of 64 – to align with GPU tensor cores and memory pages. They prioritized configuration choices that yield fast inference on accessible GPUs over absolute theoretical optimality. This is why ModernBERT can handle long contexts on a single GPU where BERT cannot. The result is an encoder that is highly optimized “under the hood” for speed and memory, without changing the core Transformer operations.

-

-

In summary, ModernBERT’s architecture retains the Transformer encoder essence of BERT but introduces improvements at almost every component: from activation functions and normalization, to positional encoding, attention sparsity, and even implementation-level tricks. These changes collectively make ModernBERT a more powerful and efficient encoder.

Training Improvements

-

ModernBERT’s training recipe was overhauled to extract maximum performance:

-

Massive Pretraining Data: ModernBERT was trained on an extremely large and diverse text corpus – 2 trillion tokens of primarily English data. This is orders of magnitude larger than BERT’s original ~3 billion token corpus. The data sources include web documents, news, books, scientific papers, and a significant amount of code (programming language text). By training on 2×10^12 tokens, ModernBERT taps into far more linguistic knowledge and diverse writing styles, including technical and programming content that BERT never saw. This vast corpus helps the model generalize broadly and even excel in domains like coding tasks (as we will see). The training dataset was carefully balanced via ablation studies to optimize performance across tasks and avoid over-focusing on any single domain.

-

Tokenizer and Vocabulary: Instead of using BERT’s WordPiece tokenizer and 30k vocabulary, ModernBERT uses a modern Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer with a larger vocab of 50,368 tokens. This tokenizer (adapted from OLMo’s tokenizer) yields more efficient subword segmentation, especially for code (it can handle programming symbols and indents better). The vocabulary size is larger to cover more tokens (useful for code and rare words) and was deliberately chosen to be a multiple of 64 for GPU efficiency. Importantly, it still includes the original special tokens (

[CLS],[SEP], etc.) so that ModernBERT remains backward-compatible with BERT’s format. -

Sequence Length and Packing: ModernBERT was trained from scratch with a sequence length of 8192 tokens, never limiting itself to 512 like original BERT. To make training on such long sequences feasible, techniques like sequence packing were used: multiple shorter texts are concatenated into one sequence with separators so that each training sequence is densely filled (~99% packing efficiency). Combined with the unpadding mechanism, this meant ModernBERT could fully utilize its long context window in training, learning long-range dependencies across documents. By contrast, BERT’s training seldom saw examples beyond a few hundred tokens, limiting its long-context understanding.

-

Optimized Training Objective: ModernBERT uses only the Masked Language Modeling (MLM) objective and drops Next Sentence Prediction (NSP). Research showed NSP did not help and even slightly hurt performance (RoBERTa had removed it). Removing NSP avoids its overhead and allows focusing on MLM. Moreover, ModernBERT uses a higher masking rate (30% of tokens masked) during MLM pretraining. This was found to be more effective than the original 15%, forcing the model to predict more tokens and possibly preventing it from simply copying many unmasked words. The result is a richer pretraining signal per sequence. These choices were informed by recent work like MosaicBERT and Cramming, which found high-mask MLM without NSP speeds up learning.

-

Advanced Optimization Techniques: The training used the StableAdamW optimizer, which modifies AdamW with Adafactor-style update clipping to stabilize the learning of very large models. This per-parameter adaptive LR clipping prevented spikes in gradient updates and proved superior to standard gradient clipping for downstream task performance. The learning rate schedule was also tailored: ModernBERT used a warmup + stable + decay (trapezoidal) schedule. It ramps up, then holds a constant learning rate for the majority of training (this long flat period is like training at a fixed high LR), then decays at the end. Such a schedule was shown to match the results of more complex cosine schedules, while making it easier to continue training beyond the initial horizon without diverging. In practice, ModernBERT-base was trained at a constant 8e-4 learning rate for 1.7 trillion tokens (with a 3B token warmup). ModernBERT-large was initialized from the base model’s weights (see below) and trained with a peak LR 5e-4 for ~1.7T tokens as well, with a slight reset halfway to recover from an instability.

-

Progressive Scaling (Knowledge Transfer): A clever strategy used was to initialize larger models from smaller ones. The authors first fully trained ModernBERT-base (149M params). Then, for ModernBERT-large (395M), instead of training from random initialization, they initialize its layers from the base model’s weights – essentially “growing” the model. They employed a technique called center tiling with Gopher layer scaling (inspired by the Phi model family) to map the 22-layer base onto the 28-layer large model. Extra layers were initialized by copying weights from base (centered appropriately in new matrices) and scaling norms accordingly. This gave the large model a “warm start,” leading to a much faster convergence than training from scratch. Essentially, ModernBERT-large benefited from the knowledge ModernBERT-base had already learned over 2T tokens. This two-stage training (train base → use it to seed large) is an example of scaling to larger models efficiently, and it ensured stability — the large model did not diverge early in training as it might have from random init. BERT did not employ this because only base/large were trained independently, but ModernBERT’s approach is akin to how one might upscale with curriculum.

-

-

Thanks to these improvements in data and optimization, ModernBERT was trained to convergence on huge data without diverging, and it captured much more information (including coding knowledge) than BERT. The training innovations are a significant factor in ModernBERT’s strong performance on downstream tasks.

Performance Benchmarks and Efficiency Gains

-

ModernBERT achieves state-of-the-art performance across a wide array of NLP tasks while being markedly more efficient than original BERT (and even surpassing other improved BERT-like models such as RoBERTa and DeBERTa). We highlight some key results:

-

General Language Understanding (GLUE Benchmark): On the GLUE benchmark, ModernBERT delivers record-breaking results for an MLM-based model. ModernBERT-base surpassed all prior base-size encoders, becoming the first MLM-trained model to outperform DeBERTa-V3 base (which used a different pretraining objective). This was a surprise, as DeBERTa had long been the strongest base model. ModernBERT-large came very close to DeBERTa-V3 large, despite having 10% fewer parameters, and achieves this while running inference about 2× faster. In fact, ModernBERT-base set a new state-of-the-art on GLUE, and ModernBERT-large is the second-best encoder on GLUE (just shy of DeBERTaV3-large’s score). This confirms that the architectural and training tweaks (despite using the standard MLM loss) translated into better natural language understanding ability.

-

Domain-Specific and Long-Context Tasks: ModernBERT particularly shines in domains that the original BERT struggled with. For instance, in code retrieval and understanding tasks, ModernBERT is in a class of its own, thanks to the inclusion of code in pretraining. On a code-heavy benchmark like StackOverflow Question-Answering, ModernBERT-large is the only encoder to exceed an 80% score, vastly outperforming RoBERTa or XLM-R which were not trained on code. For long-context information retrieval (evaluated via ColBERT-style multi-vector retrieval tasks), ModernBERT also achieves SOTA, scoring ~9 points higher than the next best model. These tasks involve understanding very long text (up to thousands of tokens) and fine-grained retrieval – areas where BERT’s 512-token limit and lack of long-range modeling would fail. ModernBERT’s 8192-token context and alternating attention make it arguably the first encoder that natively performs well on such long-document tasks.

-

Efficiency and Inference Speed: One of ModernBERT’s most impressive aspects is achieving the above performance without sacrificing efficiency – in fact, it is substantially faster and more memory-efficient than BERT. Empirical speed tests show that ModernBERT processes short inputs about 2× faster than DeBERTa-V3 and long inputs about 2–3× faster than any other encoder of comparable quality. Its optimized attention (with local patterns and FlashAttention) gives it a huge edge on long sequences. For example, at 8k token length, ModernBERT can throughput nearly 3× the tokens per second of models like NomicBERT or GTE. In terms of memory, ModernBERT-base can handle twice the batch size of BERT-base for the same input length, and ModernBERT-large can handle 60% larger batches than BERT-large on long inputs. This means it makes far better use of GPU memory, enabling larger deployments or faster processing by batching more. The end result: ModernBERT is both a better and a cheaper model to run compared to original BERT. It is designed to run on common GPUs (even gaming GPUs like RTX 3090) for 8k inputs, which was infeasible for BERT.

-

Overall Effectiveness: Taken together, ModernBERT represents a generational leap over the original BERT. It consistently outperforms BERT and RoBERTa on classification tasks (GLUE, SQuAD QA, etc.) and vastly so on retrieval and code tasks. And it achieves this while setting new records in encoder inference efficiency. In other words, ModernBERT is Pareto-superior: it is strictly better in both speed and accuracy. It demonstrates that many of the advancements from the era of large decoder models (LLMs) can be back-ported to encoders – yielding a model that is smarter (more accurate), better (can handle more context and domains), faster, and longer (long-sequence capable). The only limitation noted by its authors is that ModernBERT was trained only on English text (plus code). This leaves a gap for non-English languages – a gap that EuroBERT is meant to fill.

-

EuroBERT

- EuroBERT is another advanced Transformer encoder, released in 2025, that specifically focuses on multilingual capabilities, picking up where ModernBERT left off by covering a diverse set of languages (primarily European languages). EuroBERT can be seen as a multilingual cousin of ModernBERT – it integrates many of the same modernizations in architecture and training while scaling up the model size and data to handle multiple languages and even domains like mathematics and code. In this section, we detail how EuroBERT differs from both original BERT and ModernBERT, with an emphasis on its multilingual prowess, training regimen, and performance results.

Architecture and Features

-

EuroBERT’s architecture builds upon the lessons of ModernBERT but with some unique choices to better serve a multilingual model:

-

Multilingual Encoder Design: Unlike original BERT, which had a single 110M model for all languages (mBERT), EuroBERT comes in a family of sizes (210M “base,” 610M, and 2.1B parameter models) explicitly designed for multilingual learning. All EuroBERT models share the same architecture pattern, which is an encoder-only Transformer similar to BERT/ModernBERT, but with modifications to efficiently handle 15 different languages and large vocabulary. The vocabulary is significantly larger than English BERT’s to include tokens from many languages (covering various scripts and character sets), ensuring EuroBERT can represent text in languages ranging from English and Spanish to German, French, Italian, Portuguese, and other widely spoken European tongues. By scaling model capacity (up to 2.1B) and vocab, EuroBERT avoids the “capacity dilution” issue where a fixed-size model struggles to learn many languages simultaneously. In essence, EuroBERT allocates enough parameters to learn rich representations for each language while also benefiting from cross-lingual transfer.

-

Grouped-Query Attention (GQA): One novel architectural feature in EuroBERT is the use of Grouped-Query Attention (GQA). GQA is an efficient attention mechanism that lies between multi-head attention and multi-query attention. In multi-query attention (MQA), all heads share one Key/Value pair to reduce memory, whereas in standard multi-head, each head has its own Key/Value. GQA groups the attention heads into a small number of groups, with heads in each group sharing Key/Value projections. This greatly reduces the number of key/value projections (and associated parameters) while maintaining more flexibility than MQA. EuroBERT leverages GQA to mitigate the computational cost of multi-head self-attention for a large model, especially beneficial for handling long sequences and many languages. By adopting GQA, EuroBERT can use fewer attention parameters per layer without hurting performance, effectively achieving speed/memory closer to multi-query attention but quality closer to full multi-head. This is a modern trick (used in some large LLMs) that EuroBERT brings into an encoder model, something original BERT did not have.

-

Rotary Position Embeddings and Long Context: Similar to ModernBERT, EuroBERT uses Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE) instead of absolute positional embeddings. This choice allows EuroBERT to support very long context lengths – up to 8,192 tokens natively – even though it’s trained on multilingual data. RoPE provides a consistent way to encode positions across languages and is crucial for EuroBERT’s long-text capabilities (e.g., long document retrieval or cross-lingual context understanding). With RoPE, EuroBERT does not have a hardwired position embedding limit like mBERT did.

-

Normalization and Activation: EuroBERT replaces standard LayerNorm with Root Mean Square Layer Normalization (RMSNorm). RMSNorm omits the mean-centering step and normalizes only by the root-mean-square of activations, typically with a scale parameter but no bias. This normalization is computationally simpler and was found to improve training stability in very large models.

-

Model Scale: With a largest version of 2.1B parameters, EuroBERT is much bigger than BERT-large (which was 340M). This scale is comparable to some mid-sized decoder LLMs, indicating the ambition to achieve top-tier performance. The availability of a 210M and 610M version is also notable – these smaller models cater to those needing faster or lighter models while still benefiting from the same training pipeline. Original BERT didn’t explore such scale for encoders, so EuroBERT demonstrates how far encoders have come in terms of size.

-

Multilingual Training and Enhanced Dataset

-

Training a powerful multilingual model like EuroBERT required advances in data collection and training strategy:

-

Massive Multilingual Corpus (5 Trillion Tokens): EuroBERT was trained on an extremely large corpus of about 5 trillion tokens spanning 15 languages. This dataset dwarfs what any prior multilingual encoder used. For example, mBERT’s Wikipedia corpus had only billions of tokens, and XLM-R’s CommonCrawl data was approximately 0.5–0.6 trillion tokens for 100 languages. EuroBERT’s 5T token corpus, focused on a curated set of predominantly European languages, means each language got a huge amount of training data. Likely sources include massive web crawls, multilingual web encyclopedias, news, books, and possibly translated texts to ensure each language has both raw data and parallel data for cross-lingual alignment. By training on such scale, EuroBERT can capture nuances of each language and also learn cross-lingual representations (since the Transformer will inevitably see translation-equivalent sentences across languages). This broad coverage directly addresses BERT’s limitation of narrow training data in other languages.

-

Coverage of Diverse Tasks (Code, Math, etc.): Interestingly, EuroBERT’s training set wasn’t limited to just natural language text. It explicitly included programming code data and mathematical data (e.g. mathematical texts or formulas) in the pretraining mix. The motivation is to endow the model with specialized knowledge in these domains. Code data helps with structural understanding and might improve logical reasoning as well as code search tasks. Mathematical data (like formulas or scientific text) can improve the model’s ability to handle structured information and reasoning (for example, solving or understanding math word problems or performing numeric reasoning). This is a departure from original BERT, which had no notion of code or math. It is also beyond ModernBERT, which did include code but not specifically math-focused data. EuroBERT’s inclusion of these indicates an attempt to create a general-purpose encoder not just for language but also technical domains. As we’ll see, this pays off in strong performance on tasks like CodeSearchNet (code retrieval) and Math understanding.

-

Two-Phase Training (Pretraining + Annealing): EuroBERT employed a two-phase training pipeline. In the first phase, standard masked language modeling pretraining is done on the massive multilingual corpus, teaching the model general language understanding. In the second annealing phase, the training objective or data distribution is adjusted to fine-tune the model for downstream performance. For example, the masking ratio may be lowered in the second phase, which means the model in later training sees more unmasked text and thus starts to shift from pure token prediction to more holistic sequence understanding (closer to fine-tuning conditions). They also may re-weight the data – perhaps increasing the proportion of under-represented languages or harder tasks to ensure the model solidifies its skills there. This annealing resembles a curriculum: after the model learns basics, it’s fed data to target specific capabilities. Such a strategy was not used in original BERT (one-phase training) and shows the sophistication in EuroBERT’s training. The EuroBERT team reports doing extensive ablation studies on things like data quality filters, masking strategies, and language balances to find the best recipe. This level of careful tuning was likely necessary to get optimal multilingual results without any one aspect dominating (e.g., to prevent high-resource languages from overwhelming low-resource ones, and to balance code vs natural text, etc.).

-

Continual Checkpoints and Open Training: EuroBERT’s training pipeline also emphasized reproducibility – they released intermediate checkpoints from various stages of training. This is valuable for research, allowing analysis of how multilingual skills develop over training, and enabling possibly to fine-tune from a partially trained model for specialized purposes. It echoes ModernBERT’s practice (they also released intermediate checkpoints). From a technical perspective, training a 2.1B parameter model on 5T tokens is an enormous undertaking – likely done on large GPU clusters with mixed precision (bfloat16 or FP16). Techniques like ZeRO or sharded training were presumably used to handle model and data parallelism. The outcome is a set of robust multilingual encoders that encapsulate knowledge from a vast corpus.

-

Performance Results of EuroBERT

-

EuroBERT delivers state-of-the-art results in multilingual NLP tasks, significantly outperforming prior models like mBERT, XLM-R, and others. Here are some highlights of its performance and enhancements:

-

Multilingual Understanding and Retrieval: EuroBERT achieves top scores on multilingual benchmarks. For example, on the MIRACL multilingual retrieval dataset, EuroBERT outperforms existing models in ranking documents. A comparison of retrieval metrics (nDCG@10) shows EuroBERT ranking first. In Wikipedia and news retrieval tasks, EuroBERT similarly leads. On XNLI (cross-lingual NLI) and PAWS-X (cross-lingual paraphrase) classification, EuroBERT’s accuracy is on par with or above the previous best (often beating XLM-R and mDeBERTa). Crucially, it does this not just for high-resource languages but across the board – it improved especially on languages that were underperforming with earlier models. This indicates the 15-language focus hit a sweet spot: enough languages to be generally useful, not so many that capacity is spread thin.

-

Cross-Lingual Transfer: EuroBERT demonstrates excellent cross-lingual transfer learning. Because it’s a single model for all 15 languages, you can fine-tune it on a task in one language and it performs well in others. This was a key property of mBERT and XLM-R as well, but EuroBERT’s stronger base representations take it further. For instance, tasks like multilingual QA or translation ranking see EuroBERT setting new highs. In one report, EuroBERT improved average accuracy on a suite of cross-lingual benchmarks by significant margins over XLM-R (which itself was approximately 14% over mBERT) – reflecting the impact of its larger size and better training.

-

Domain-Specific Tasks (Code and Math): One of the most striking results is EuroBERT’s performance on code-related and math-related tasks, which historically multilingual language models weren’t tested on. On CodeSearchNet (code search), EuroBERT achieves much higher NDCG scores than models like ModernBERT (English-only) or mDeBERTa (multilingual without code). It even surpasses ModernBERT on some code tasks, despite ModernBERT having code training, likely due to EuroBERT’s greater scale. Similarly, on mathematical reasoning benchmarks like MathShepherd, EuroBERT shows strong accuracy, indicating an ability to understand mathematical problems described in language. These are new capabilities that original BERT never aimed for. The inclusion of code/math in pretraining clearly paid off: where other models have near-zero ability (e.g. mDeBERTa’s score on code retrieval is extremely low), EuroBERT attains very high scores, effectively closing the gap between natural language and these specialized domains.

-

Benchmark Leader in Many Categories: Summarizing from the EuroBERT results, it is a top performer across retrieval, classification, and regression tasks in the multilingual context. It outperforms strong baselines like XLM-Roberta (XLM-R) and multilingual GTE on European languages by a significant margin. For instance, on an aggregate of European language tasks, EuroBERT’s scores are highest in essentially all categories (with statistically significant gains in many cases). This suggests that for tasks involving any of the 15 languages it covers, EuroBERT is likely the go-to model now.

-

Ablation: Monolingual vs Multilingual: Interestingly, EuroBERT closes the gap between multilingual and monolingual models. Historically, using a multilingual model for a high-resource language like English would incur a small performance drop compared to a dedicated English model (because the multilingual model had to also allocate capacity to other languages). EuroBERT’s authors note that it is competitive with monolingual models on tasks like GLUE and XNLI for English-only evaluation. This means we don’t sacrifice English performance while gaining multilingual ability – a testament to its scale and training. Essentially, EuroBERT achieves multilinguality without sacrificing per-language excellence.

-

Efficiency and Practicality: Although EuroBERT is large, it was built with deployment in mind as well. The use of GQA and efficient attention means that, for its size, EuroBERT is relatively efficient. A 2.1B encoder can be heavy, but the availability of 210M and 610M versions offers flexibility. The smaller EuroBERT-210M still handily beats older 270M–300M models like mBERT or XLM-Rbase on most tasks, while being of comparable size.

-

-

In summary, EuroBERT extends the frontier of BERT-like models into the multilingual arena, showing that by combining massive data, modern Transformer techniques, and strategic training, one can achieve superb multilingual understanding and even tackle programming and math tasks with an encoder.

ModernBERT and EuroBERT: Summary

- ModernBERT and EuroBERT demonstrably push the boundaries of what BERT started, bringing encoder models to new heights in capability and efficiency.

-

ModernBERT showed that an encoder-only Transformer can be made “Smarter, Better, Faster, Longer”: through careful architectural upgrades (like GeGLU, RoPE, alternating attention) and massive-scale training, it achieves superior accuracy on a wide range of English NLP tasks while also being significantly faster and more memory-efficient than the original BERT. It addressed BERT’s key pain points: no longer is the encoder the bottleneck for long documents or specialized domains (code) – ModernBERT handles these with ease, something unimaginable with vanilla BERT.

-

EuroBERT, on the other hand, extends this revolution to the multilingual arena. It demonstrates that BERT-like encoders can scale to dozens of languages and even outperform models like XLM-R by a substantial margin. By incorporating the latest advancements (grouped attention, huge data, etc.), EuroBERT ensures that language is no barrier – researchers and practitioners can use one model for many languages and expect top-tier results, a scenario that the original BERT could not offer. Moreover, EuroBERT’s strength on code and math tasks reveals an exciting trend: encoder models are becoming universal foundation models, not just for natural language but for structured data and reasoning as well.

- In conclusion, both ModernBERT and EuroBERT exemplify how the NLP community has built on the “BERT revolution” with years of hard-earned knowledge: better optimization, more data, and architectural ingenuity. They retain the elegance of BERT’s bidirectional encoder (non-generative, efficient inference) which is crucial for many applications, but shed its limitations. For AI/ML researchers, these models are a treasure trove of ideas – from alternating attention patterns to multilingual curriculum learning. Practically, they offer powerful new backbones for tasks like retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), where ModernBERT can encode enormous documents for search, or cross-lingual applications, where EuroBERT provides a single model for a world of languages. The development of ModernBERT and EuroBERT shows that the evolution of Transformer encoders is very much alive, and that by marrying architectural innovation with massive training, we can continue to achieve leaps in NLP performance beyond the original BERT’s legacy. These models set the stage for the next generation of research in encoder-based NLP, where we can imagine even more languages, longer contexts, and tighter integration with multimodal and knowledge-specific data – all while maintaining the efficient, grounded nature that made BERT so influential in the first place.

FAQs

In BERT, how do we go from \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\) at the final transformer block’s output to contextualized embeddings?

-

To understand how the \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\) matrices contribute to the contextualized embeddings in BERT, let’s dive into the core processes occurring in the final layer of BERT’s transformer encoder stack. Each layer performs self-attention, where the matrices \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\) interact to determine how each token attends to others in the sequence. Through this mechanism, each token’s embedding is iteratively refined across multiple layers, progressively capturing both its own attributes and its contextual relationships with other tokens.

-

By the time these computations reach the final layer, the output embeddings for each token are highly contextualized. Each token’s embedding now encapsulates not only its individual meaning but also the influence of surrounding tokens, providing a rich representation of the token in context. This final, refined embedding is what BERT ultimately uses to represent each token, balancing individual token characteristics with the nuanced context in which the token appears.

-

Let’s dive deeper into how the \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\) matrices at each layer ultimately yield embeddings that are contextualized, particularly by looking at what happens in the final layer of BERT’s transformer encoder stack. The core steps involved from self-attention outputs in the last layer to meaningful embeddings per token are:

- Self-Attention Mechanism Recap:

- In each layer, BERT computes self-attention across the sequence of tokens. For each token, it generates a query vector \(Q\), a key vector \(K\), and a value vector \(V\). These matrices are learned transformations of the token embeddings and encode how each token should attend to other tokens.

- The query vector of a token determines what information it is looking for in other tokens. The key vector of a token represents what information it has to offer. The value vector contains the actual content that will be aggregated based on attention.

- Attention Scores Calculation:

- For a given token, its query vector is compared against the key vectors of all tokens in the sequence (including itself) by computing a dot product. This produces a raw attention score for each pair of tokens, capturing how well the query matches a key.

- These raw scores are then scaled by dividing by the square root of the key dimension (often denoted \(\sqrt{d_k}\)) to prevent extremely large values, which stabilizes gradients during training.

- Mathematically, for a query vector \(q_i\) and key vector \(k_j\), the attention score is: \(\text{score}(i,j) = \frac{q_i \cdot k_j}{\sqrt{d_k}}\)

- Attention Weights Computation:

- The attention scores are passed through a softmax function along the token dimension, converting them into attention weights. These weights are positive, sum to 1 for each token’s query, and express the relative importance of each other token for the given query token.

- A high attention weight means the model considers that token highly relevant to the current token, while a low weight indicates less relevance.

- These attention weights are dynamic and vary not only across different tokens but also across different attention heads, allowing the model to capture a variety of relationships.

- Weighted Summation of Values (Producing Contextual Embeddings):

- The attention weights are then used to perform a weighted sum over the corresponding value vectors. Specifically, each token gathers information from the values of all tokens, weighted by how much attention it paid to each.

- Formally, the output vector for a token is: \(\text{output}_i = \sum_{j=1}^{n} \text{softmax}(\text{score}(i,j)) \times v_j\)

- This step fuses information from across the entire sequence, allowing a token’s representation to embed contextual cues from its surroundings.

- Passing Through Multi-Head Attention and Feed-Forward Layers:

- BERT uses multi-head attention, meaning it projects queries, keys, and values into multiple subspaces, each with its own set of learned parameters. Each head captures different types of relationships or dependencies among tokens.

- The outputs of all attention heads are concatenated and passed through another linear transformation to combine the information.

- Following the multi-head attention, a position-wise feed-forward network (consisting of two linear transformations with a non-linearity like GELU in between) is applied to further refine the token embeddings.

- Stacking Layers for Deeper Contextualization:

- The output from the multi-head attention and feed-forward block at each layer is fed as input to the next transformer layer.

- Each layer adds more sophistication to the token embeddings, allowing the model to capture higher-level abstractions and more global dependencies as the depth increases.

- By the time the model reaches the final layer, each token embedding has accumulated rich, multi-layered information about both local neighbors and distant tokens.

- Extracting Final Token Embeddings from the Last Encoder Layer:

- After the final encoder layer, the output matrix contains the final, contextualized embeddings for each token.

- For a sequence with \(n\) tokens, the shape of this matrix is \(n \times d\), where \(d\) is the hidden size (e.g., 768 for BERT-base).

- Each row corresponds to a single token’s contextualized embedding, which integrates information about the token itself and its entire sequence context.

- Embedding Interpretability and Usage:

- These final token embeddings are contextualized and highly expressive. They encode not only the surface meaning of tokens but also their syntactic roles, semantic nuances, and interdependencies with other tokens.

- Depending on the task, either individual token embeddings (e.g., for token classification) or pooled representations (e.g., [CLS] token for sentence classification) are used as inputs to downstream layers like task-specific classifiers.

What gets passed on from the output of the previous transformer block to the next in the encoder/decoder?

-

In a transformer-based architecture (such as the vanilla transformer or BERT), the output of each transformer block (or layer) becomes the input to the subsequent layer in the stack. Specifically, here’s what gets passed from one layer to the next:

-

Token Embeddings (Contextualized Representations):

- The main component passed between layers is a set of token embeddings, which are contextualized representations of each token in the sequence up to that layer.

- For a sequence of \(n\) tokens, if the embedding dimension is \(d\), the output of each layer is an \(n \times d\) matrix, where each row represents the embedding of a token, now updated with contextual information learned from the previous layer.

- Each embedding at this point reflects the token’s meaning as influenced by the other tokens it attended to in that layer.

-

Residual Connections:

- Transformers use residual connections to stabilize training and allow better gradient flow. Each layer’s output is combined with its input via a residual (or skip) connection.

- In practice, the output of the self-attention and feed-forward operations is added to the input embeddings from the previous layer, preserving information from the initial representation.

-

Layer Normalization:

- After the residual connection, layer normalization is applied to the summed representation. This normalization helps stabilize training by maintaining consistent scaling of token representations across layers.

- The layer-normalized output is then what gets passed on as the “input” to the next layer.

-

Positional Information:

- The positional embeddings (added initially to the token embeddings to account for the order of tokens in the sequence) remain embedded in the representations throughout the layers. No additional positional encoding is added between layers; instead, the attention mechanism itself maintains positional relationships indirectly.

-

Summary of the Process:

- Each layer receives an \(n \times d\) matrix (the sequence of token embeddings), which now includes contextual information from previous layers.