Primers • VLM Architectures

- Overview

- Applications

- Architectural Challenges

- Architecture

- Training Process

- Fine-Tuning Process

- Leaderboards

- Popular VLMs

- VLMs for Generation

- GPT-4V

- LLaVA

- Frozen

- Flamingo

- OpenFlamingo

- Idefics

- PaLI

- PaLM-E

- Qwen-VL

- Fuyu-8B

- SPHINX

- MIRASOL3B

- BLIP

- BLIP-2

- InstructBLIP

- MiniGPT-4

- MiniGPT-v2

- LLaVA-Plus

- BakLLaVA

- LLaVA-1.5

- CogVLM

- FERRET

- KOSMOS-1

- KOSMOS-2

- OFAMultiInstruct

- LaVIN

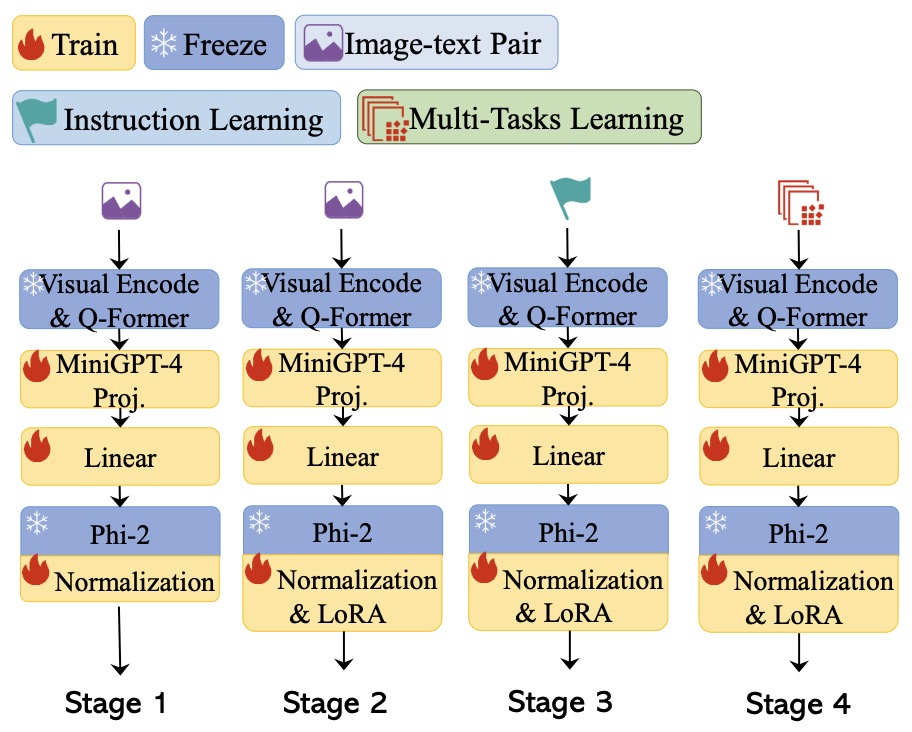

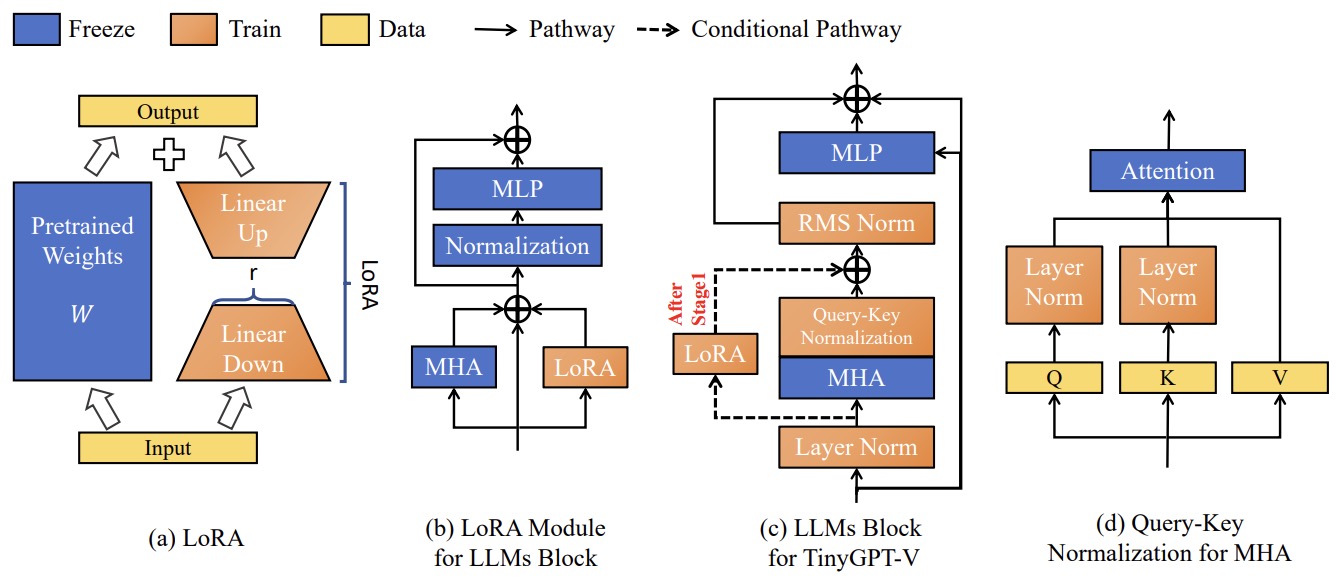

- TinyGPT-V

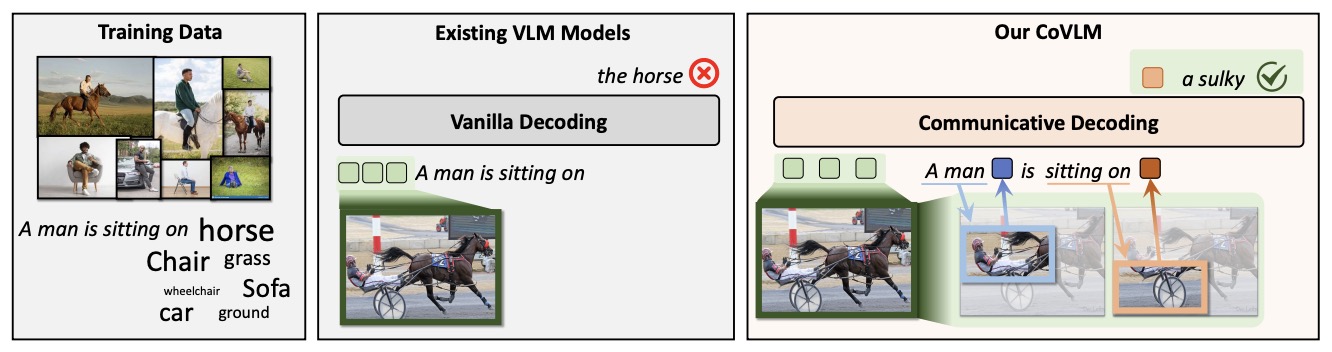

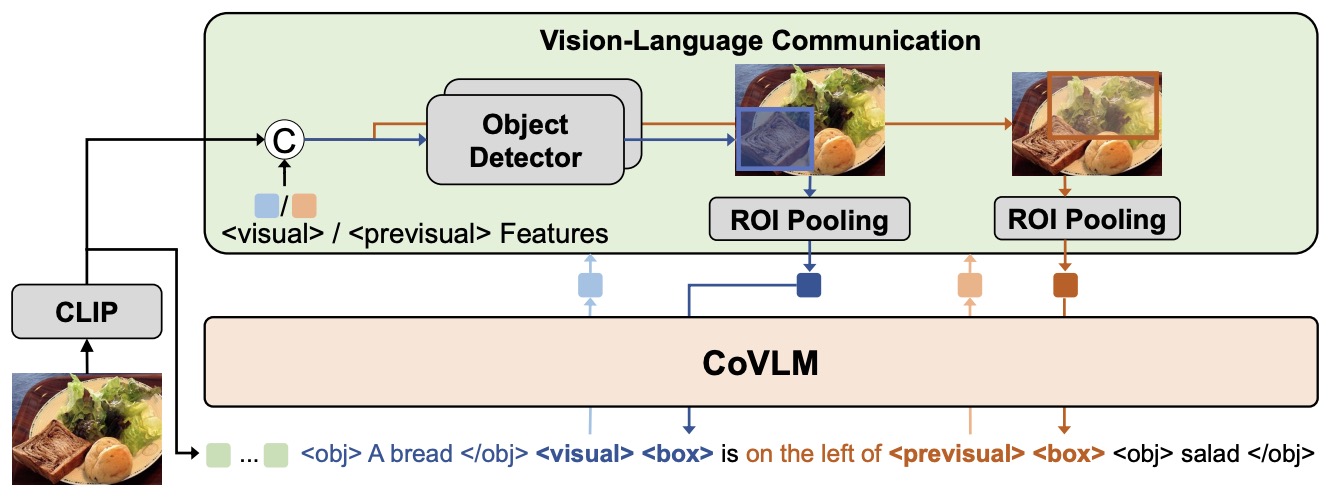

- CoVLM

- FireLLaVA

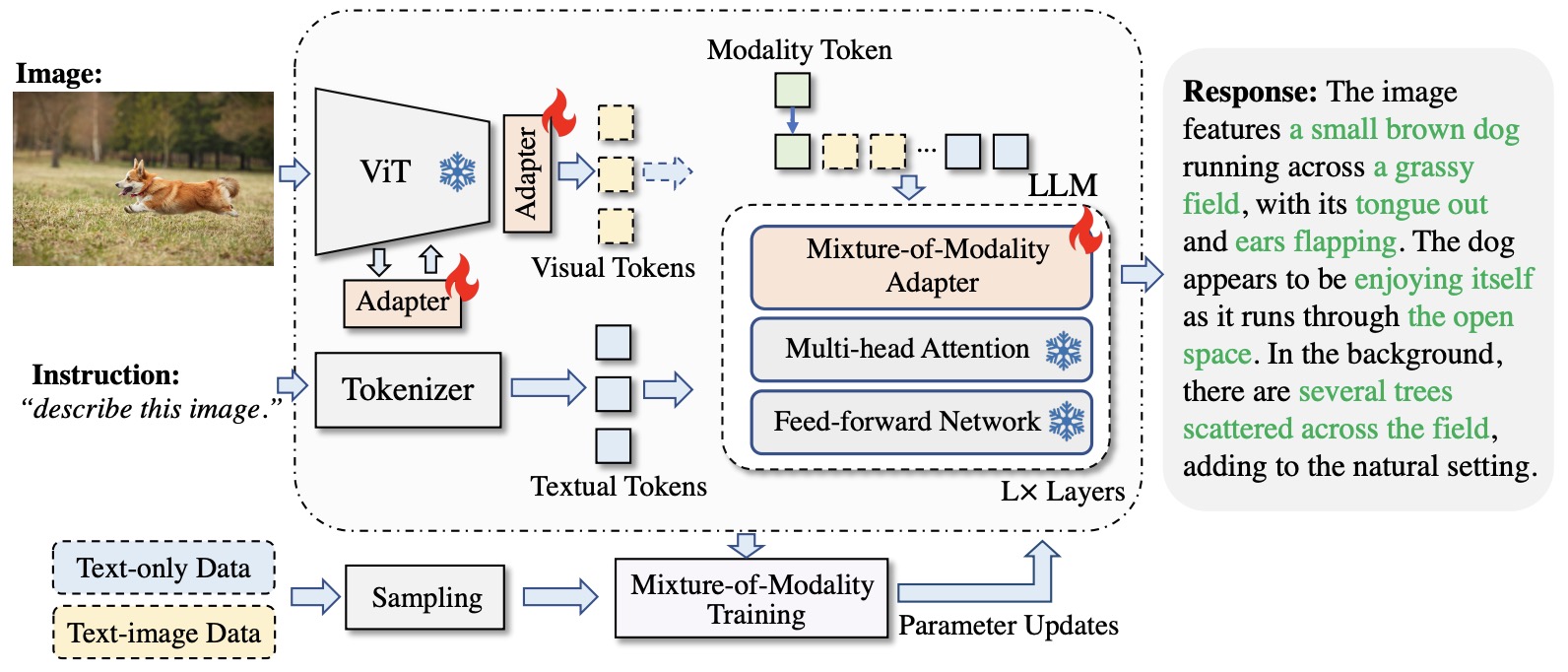

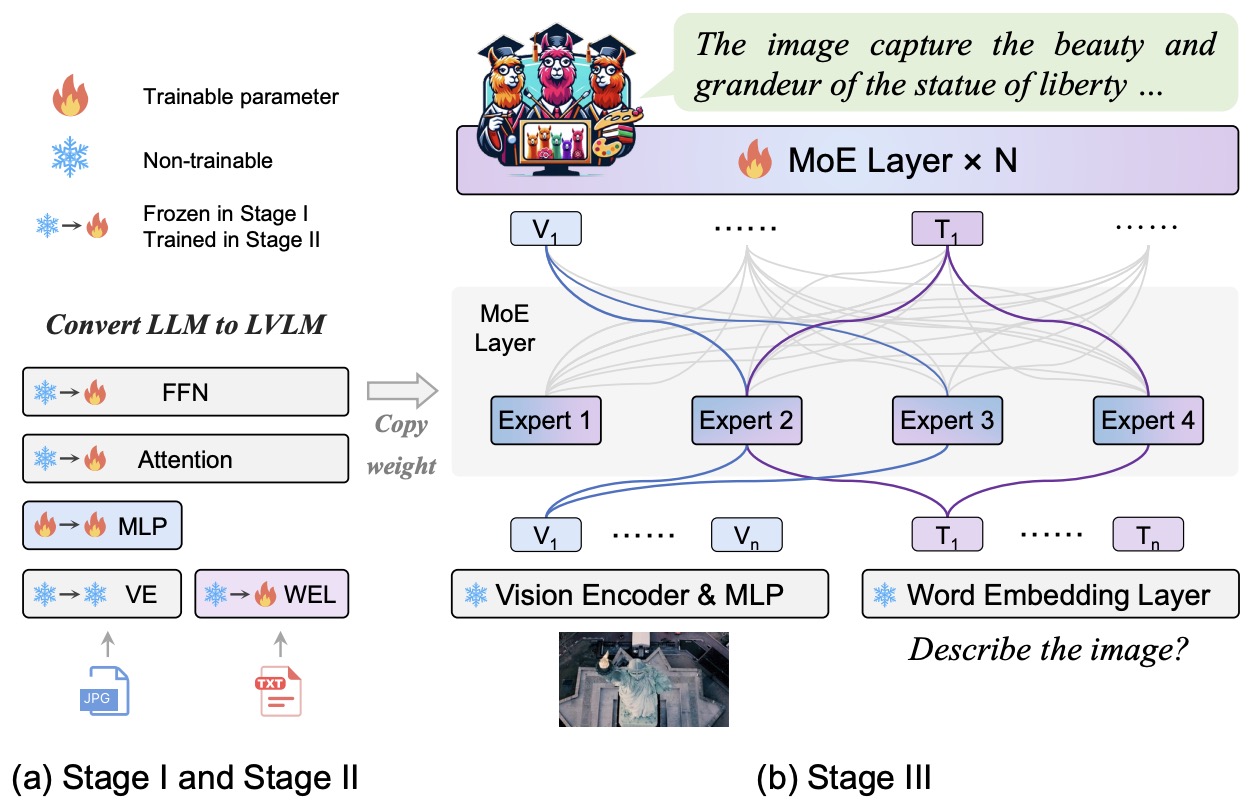

- MoE-LLaVA

- BLIVA

- PALO

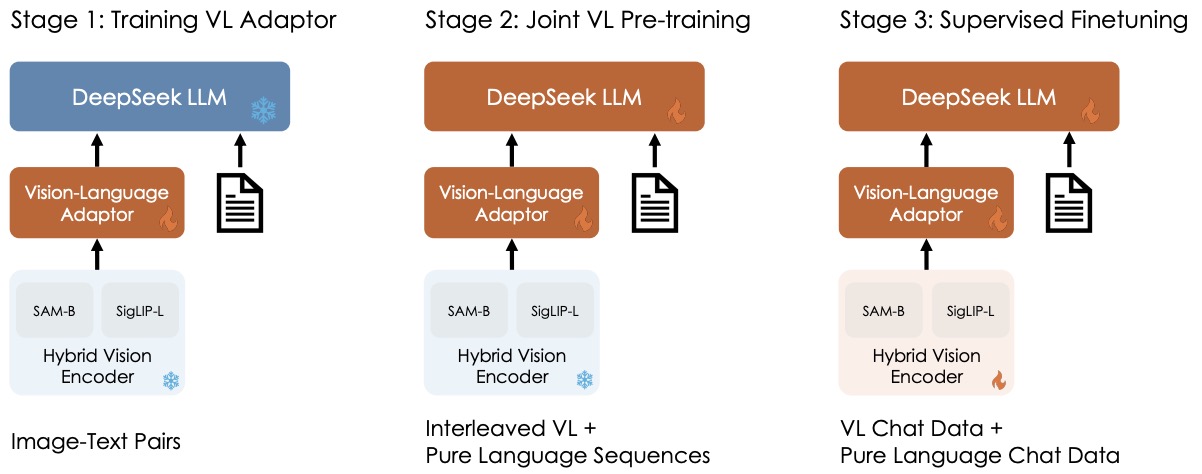

- DeepSeek-VL

- Grok-1.5 Vision

- LLaVA++

- LLaVA-NeXT

- InternVL

- Falcon 2

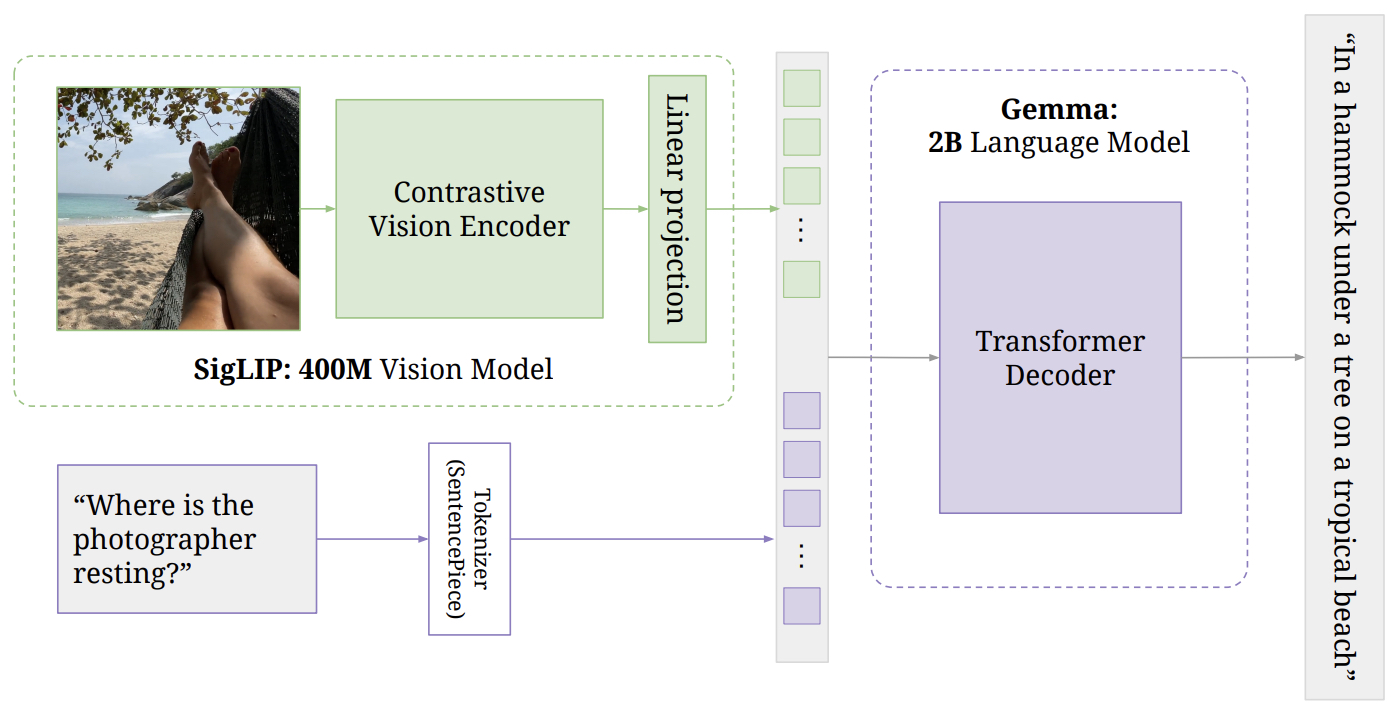

- PaliGemma

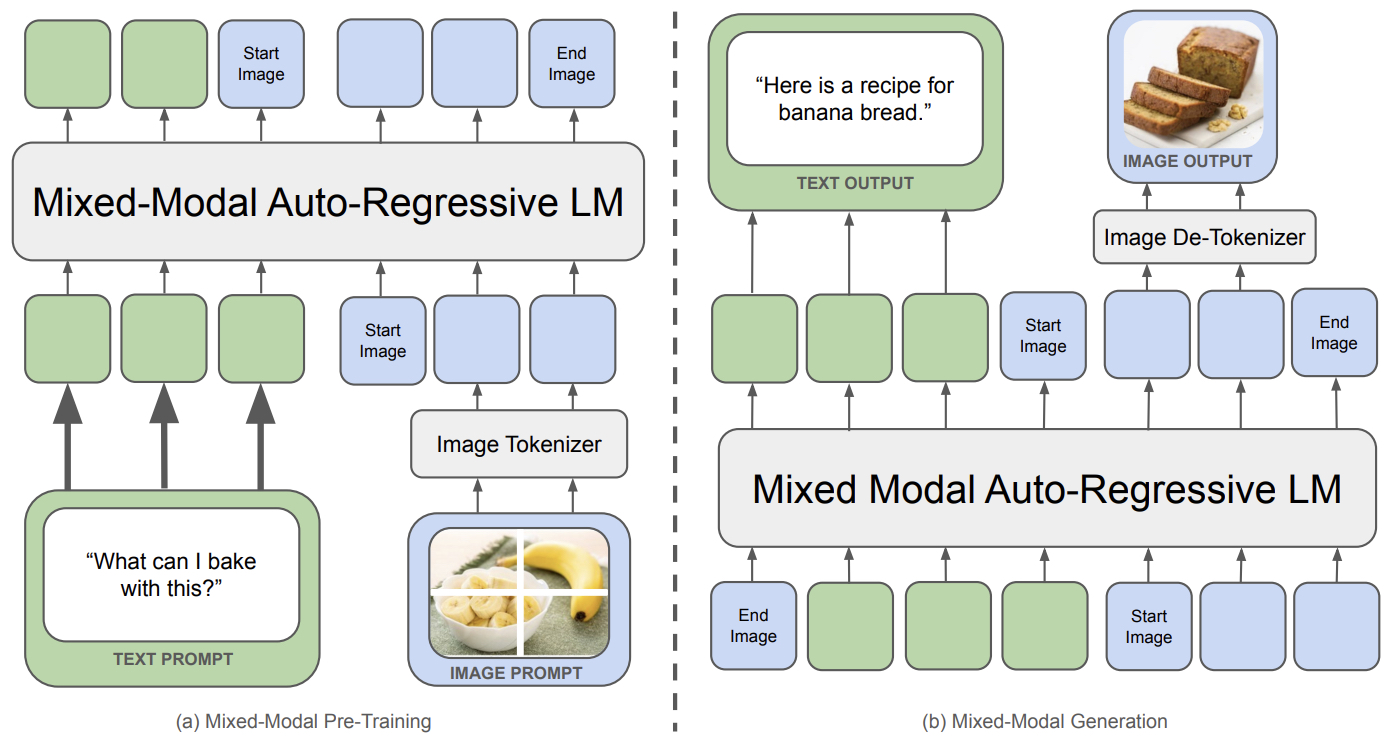

- Chameleon

- Phi-3.5-Vision

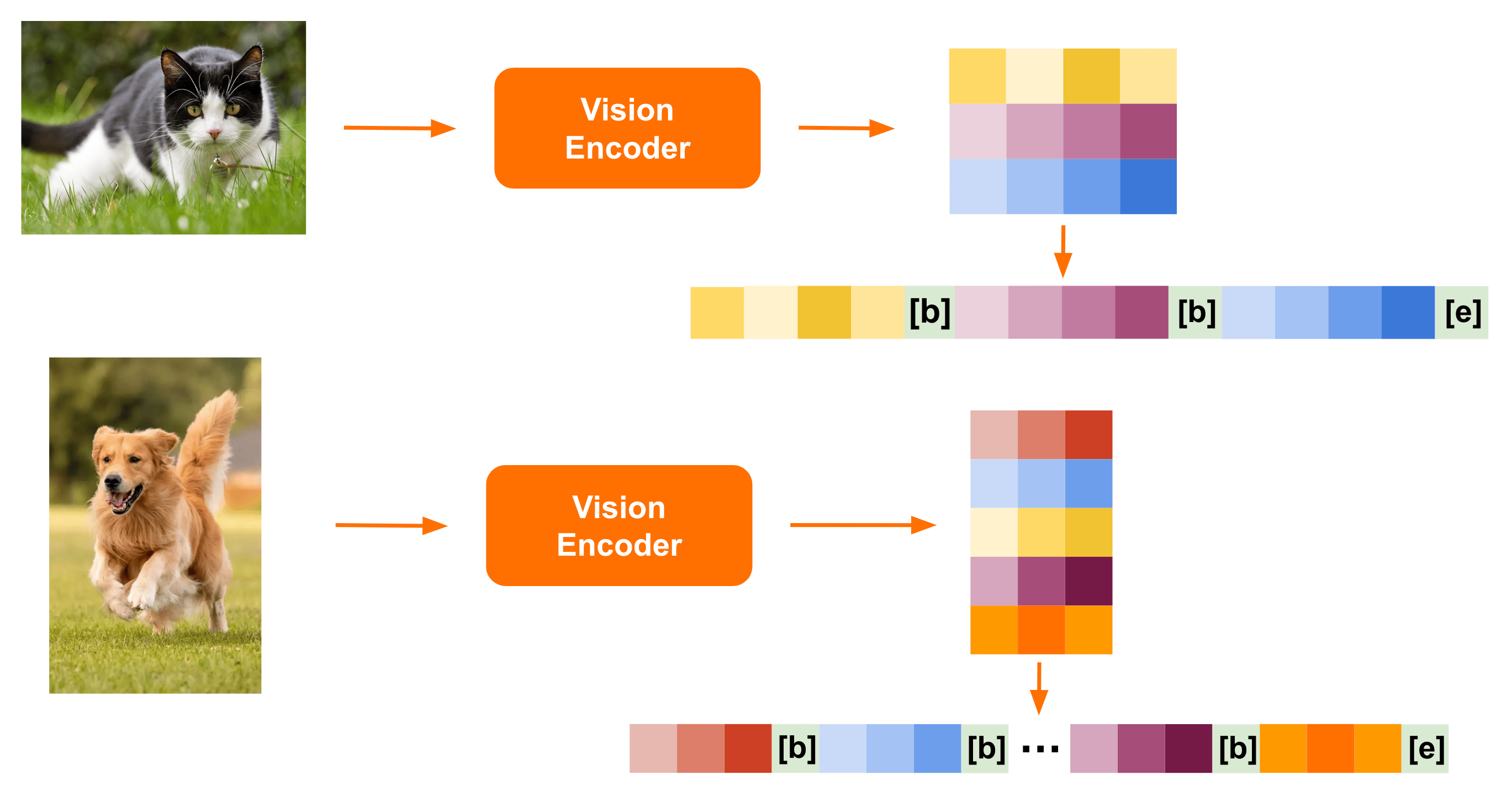

- Molmo

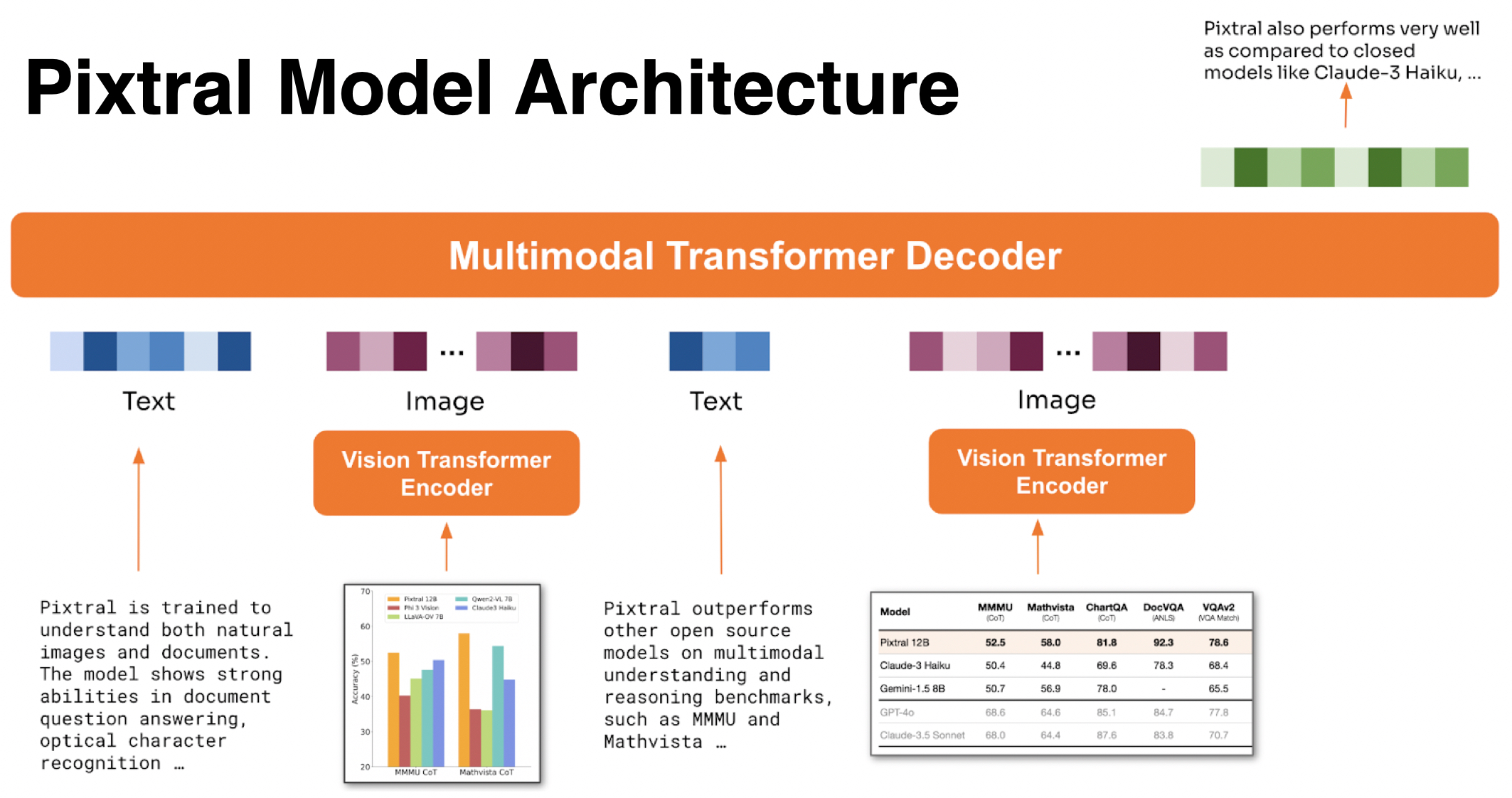

- Pixtral

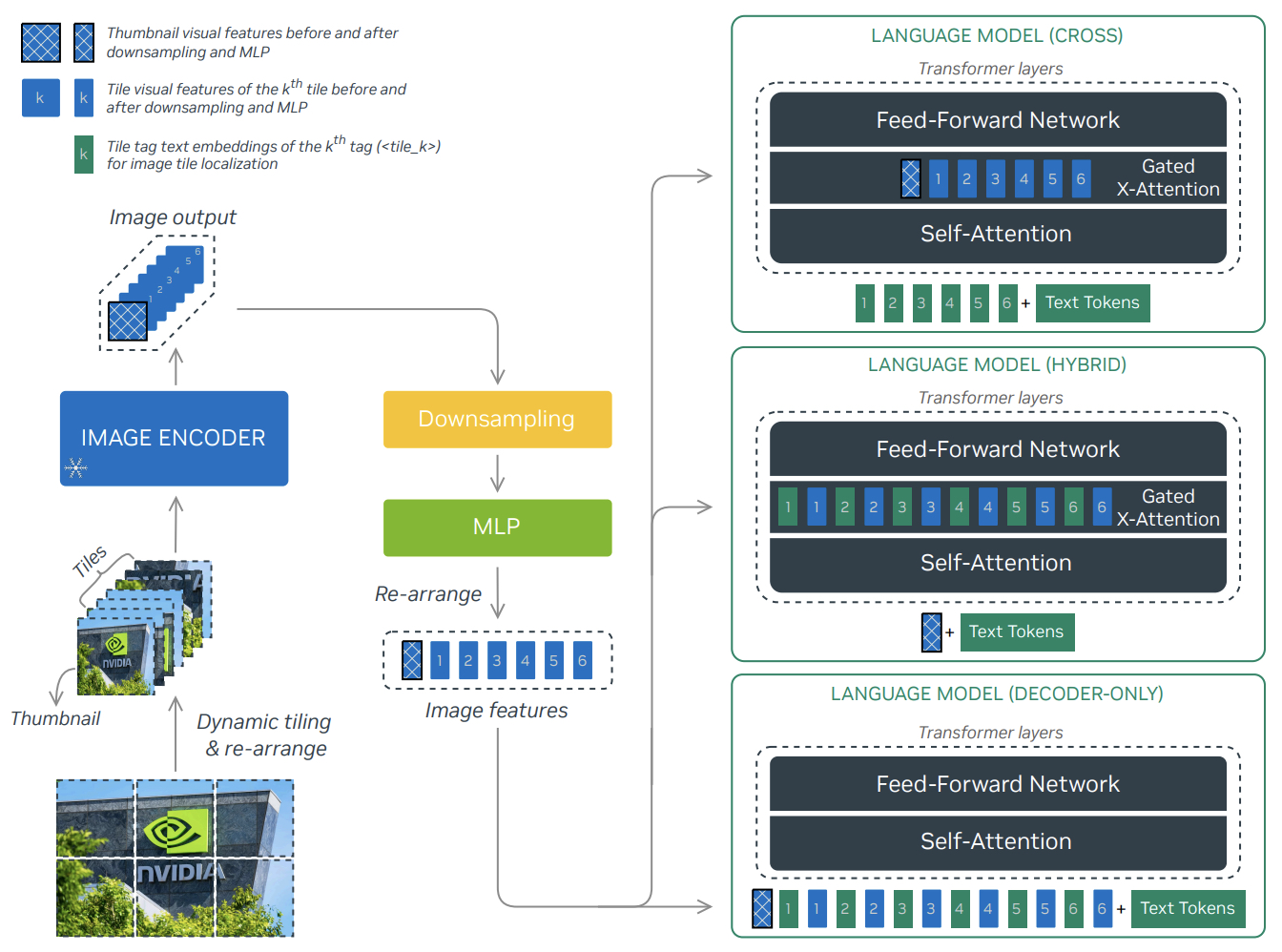

- NVLM

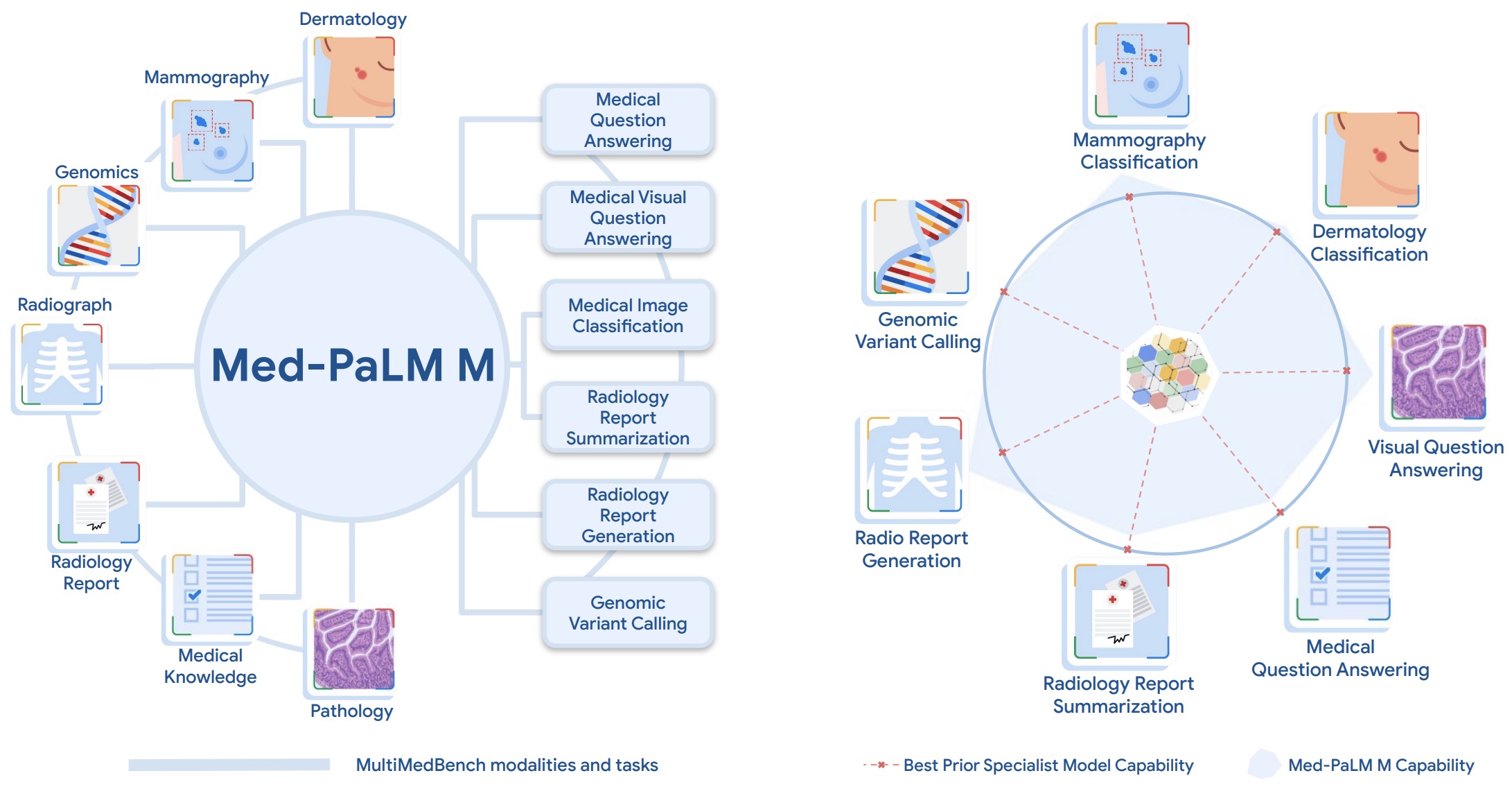

- VLMs for Understanding

- Medical VLMs for Generation

- Indic VLMs for Generation

- VLMs for Generation

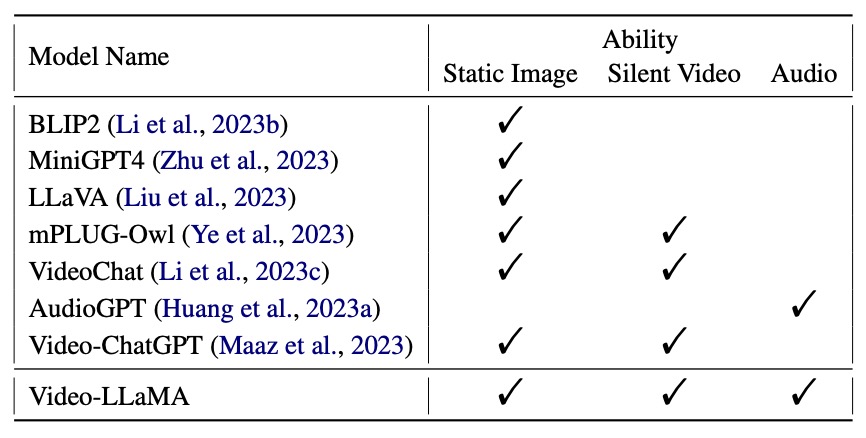

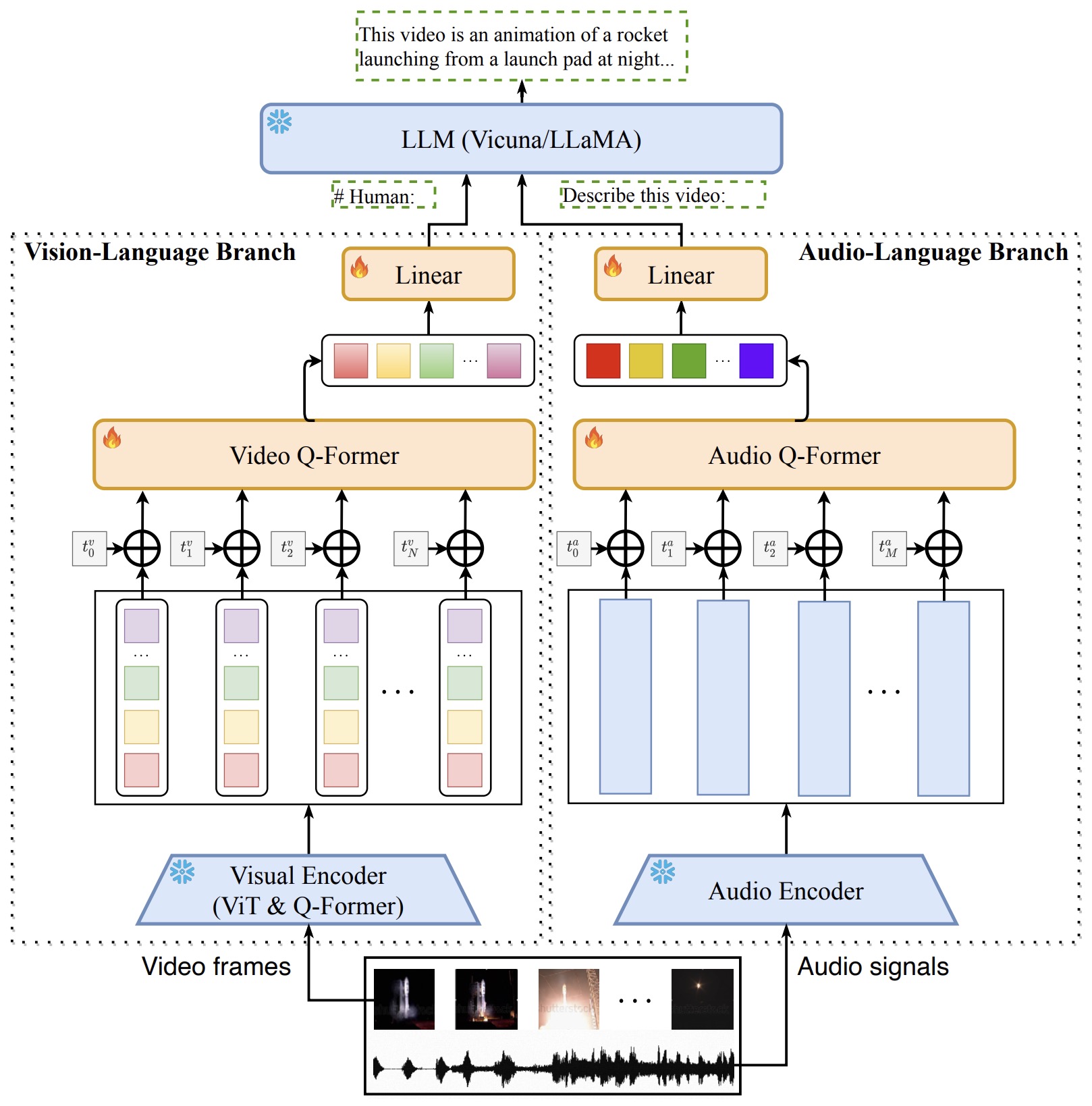

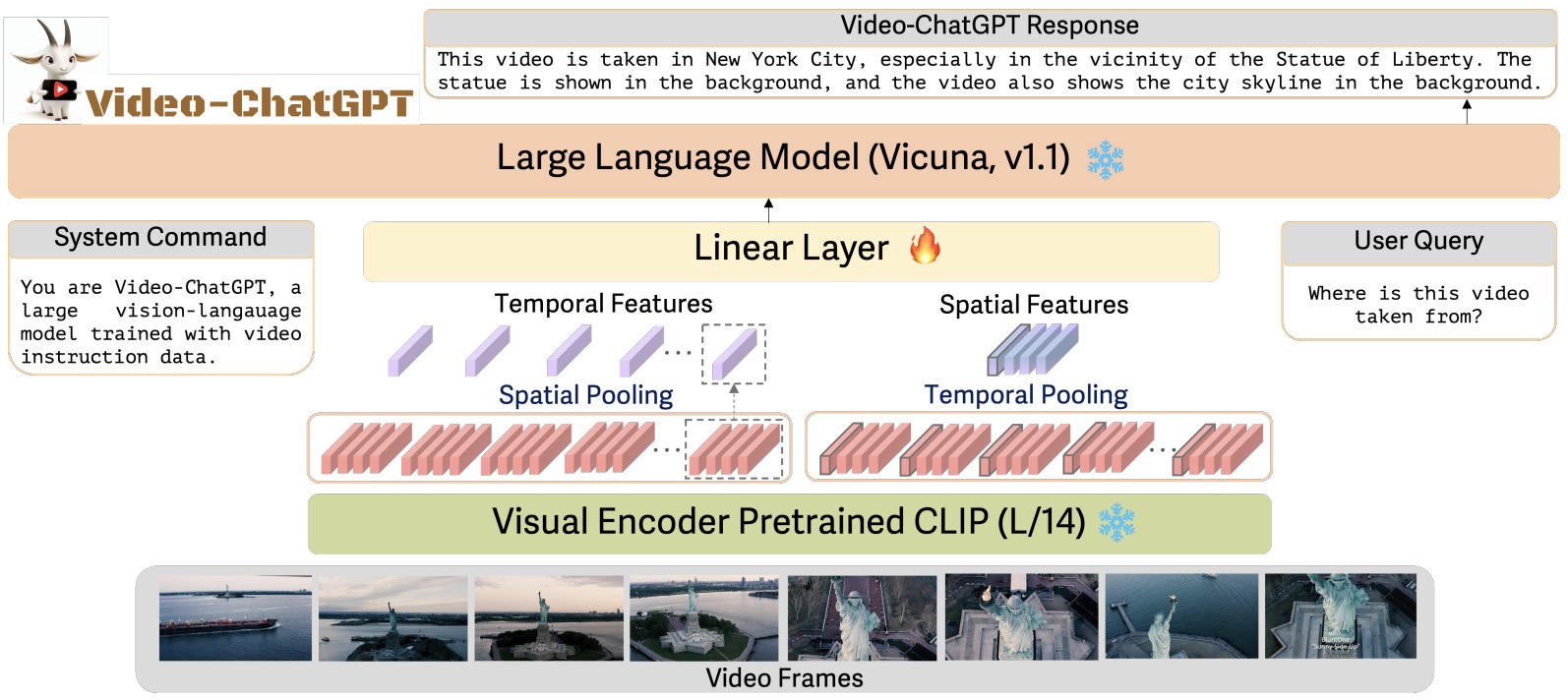

- Popular Video LLMs

- Any-to-Any VLMs

- Comparative Analysis

- Further Reading

- Citation

Overview

- Vision-Language Models (VLMs) integrate both visual (image) and textual (language) information processing. They are designed to understand and generate content that involves both images and text, enabling them to perform tasks like image captioning, visual question answering, and text-to-image generation.

- This primer offers an overview of their architecture and how they differ from Large Language Models (LLMs).

Applications

- Let’s look at a few VLM applications:

- Image Captioning: Generating descriptive text for images.

- Visual Question Answering: Answering questions based on visual content.

- Cross-modal Retrieval: Finding images based on text queries and vice versa.

Architectural Challenges

- Put succinctly, VLMs need to overcome the following challenges as part of their architectural definition and training:

- Data Alignment: Ensuring proper alignment between visual and textual data is challenging.

- Complexity: The integration of two modalities adds complexity to the model architecture and training process.

Architecture

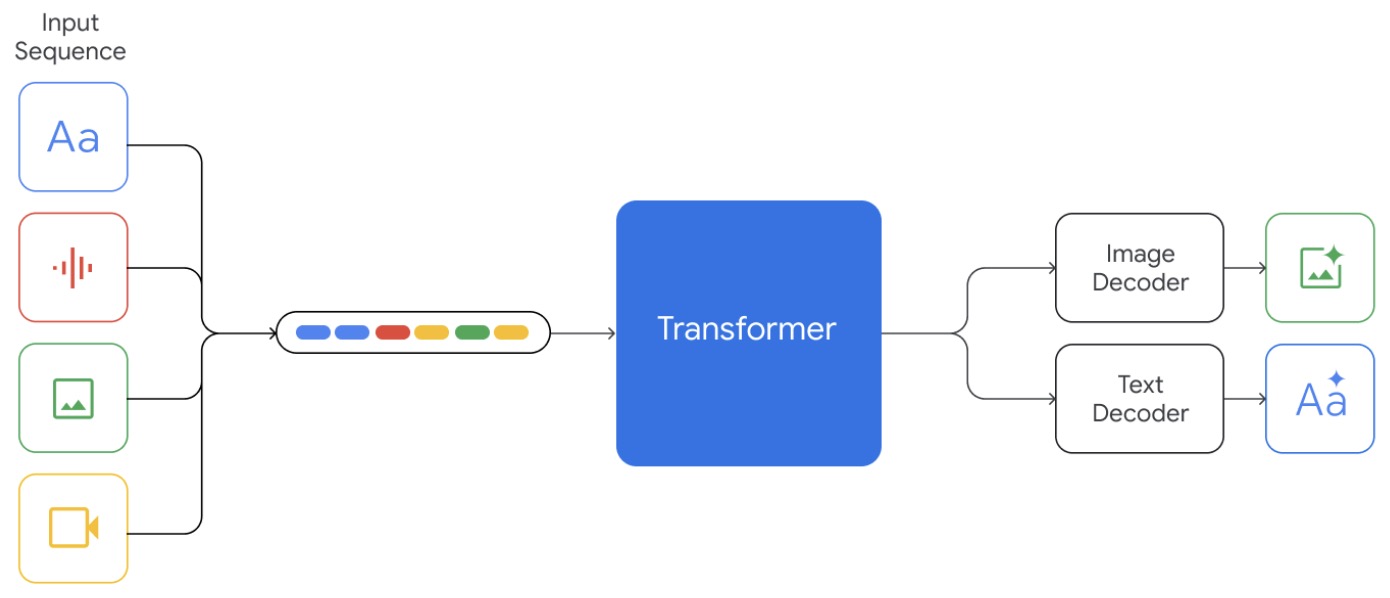

- The architecture of VLMs is centered around the effective fusion of visual and linguistic modalities, a process that requires sophisticated mechanisms to align and integrate information from both text and images.

- Let’s delve deeper into this architecture, focusing on modality fusion and alignment, and then look at some examples of popular VLMs and their architectural choices.

Architecture of Vision-Language Models

- Modality Fusion:

- Early Fusion: In this approach, visual and textual inputs are combined at an early stage, often before any deep processing. This can mean simply concatenating features or embedding both modalities into a shared space early in the model.

- Intermediate Fusion: Here, fusion occurs after some independent processing of each modality. It allows each stream to develop an intermediate understanding before integration, often through cross-modal attention mechanisms.

- Late/Decision-Level Fusion: In late fusion, both modalities are processed independently through deep layers, and fusion occurs near the output. This method keeps the modalities separate for longer, allowing for more specialized processing before integration.

- Modality Alignment:

- Cross-Modal Attention: Models often use attention mechanisms, like transformers, to align elements of one modality (e.g., objects in an image) with elements of another (e.g., words in a sentence). This helps the model understand how specific parts of an image correlate with specific textual elements.

- Joint Embedding Space: Creating a joint/shared representation space where both visual and textual features are projected. This space is designed so that semantically similar concepts from both modalities are close to each other.

- Training Strategies:

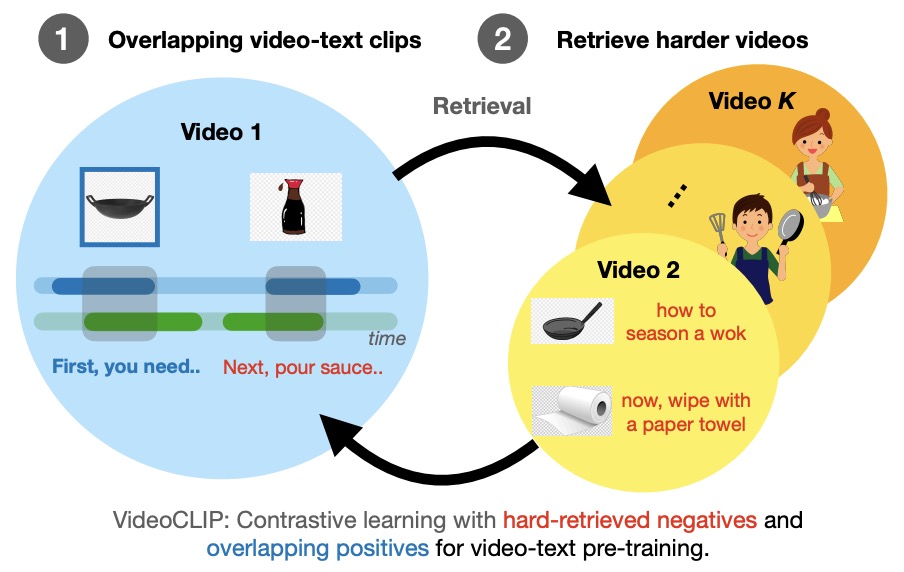

- Contrastive Learning: Often used for alignment, this involves training the model to bring closer the representations of text and images that are semantically similar and push apart those that are not.

- Multi-Task Learning: Training the model on various tasks (e.g., image captioning, visual question answering) to improve its ability to understand and integrate both modalities.

Examples of Popular VLMs and Their Architectural Choices

- Each of the below models represents a unique approach to integrating and aligning text and image data, showcasing the diverse methodologies within the field of VLMs. The choice of architecture and fusion strategy depends largely on the specific application and the nature of the tasks the model is designed to perform.

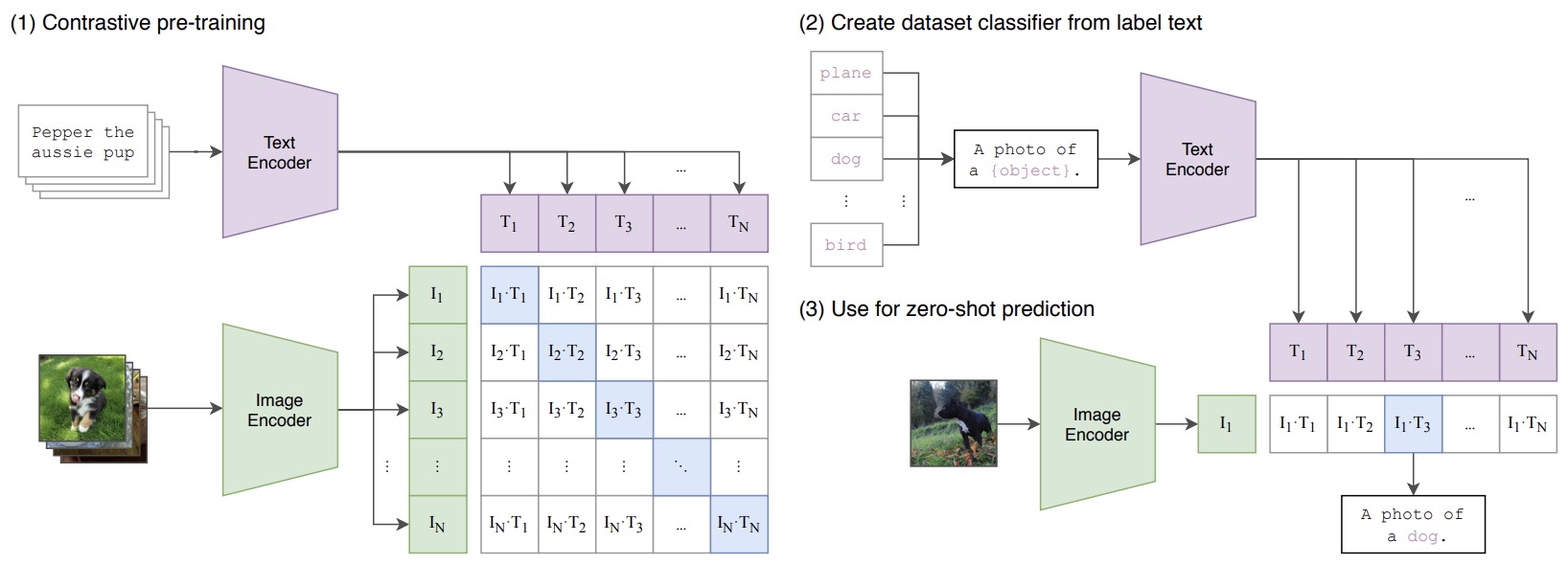

- CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pretraining):

- Architecture: Uses a transformer for text and a ResNet (or a Vision Transformer) for images.

- Fusion Strategy: Late fusion, with a focus on learning a joint embedding space.

- Alignment Method: Trained using contrastive learning, where image-text pairs are aligned in a shared embedding space.

- DALL-E:

- Architecture: Based on the GPT-3 architecture, adapted to handle both text and image tokens.

- Fusion Strategy: Early to intermediate fusion, where text and image features are processed in an intertwined manner.

- Alignment Method: Uses an autoregressive model that understands text and image features in a sequential manner.

- VisualBERT:

- Architecture: A BERT-like model that processes both visual and textual information.

- Fusion Strategy: Intermediate fusion with cross-modal attention mechanisms.

- Alignment Method: Aligns text and image features using attention within a transformer framework.

- LXMERT (Learning Cross-Modality Encoder Representations from Transformers):

- Architecture: Specifically designed for vision-and-language tasks, uses separate encoders for language and vision, followed by a cross-modality encoder.

- Fusion Strategy: Intermediate fusion with a dedicated cross-modal encoder.

- Alignment Method: Employs cross-modal attention between language and vision encoders.

VLM: Differences from Large Language Models (LLMs)

- Input Modalities:

- VLMs: Handle both visual (images) and textual (language) inputs.

- LLMs: Primarily focused on processing and generating textual content.

- Task Versatility:

- VLMs: Capable of tasks that require understanding and correlating information from both visual and textual data, like image captioning, visual storytelling, etc.

- LLMs: Specialize in tasks that involve only text, such as language translation, text generation, question answering purely based on text, etc.

-

Complexity in Integration: VLMs involve a more complex architecture due to the need to integrate and correlate information from two different modalities (visual and textual), whereas LLMs deal with a single modality.

- Use Cases: VLMs are particularly useful in scenarios where both visual and textual understanding is crucial, such as in social media analysis, where both image and text content are prevalent. LLMs are more focused on applications like text summarization, chatbots, and content creation where the primary medium is text.

- In summary, while both VLMs and LLMs are advanced AI models leveraging deep learning, VLMs stand out for their ability to understand and synthesize information from both visual and textual data, offering a broader range of applications that require multimodal understanding.

Connecting Vision and Language via VLMs

- Vision-Language Models (VLMs) are designed to understand and generate content that combines both visual and textual data. To effectively integrate these two distinct modalities—vision and language—VLMs use specialized mechanisms, such as adapters and linear layers.

- This section details popular building blocks that various VLMs utilize to link visual and language input. Let’s delve into how these components work in the context of VLMs.

Adapters/MLPs/Fully Connected Layers in VLMs

-

Purpose of Adapters: Adapters are small neural network modules inserted into pre-existing models. In the context of VLMs, they facilitate the integration of visual and textual data by transforming the representations from one modality to be compatible with the other.

-

Functioning: Adapters typically consist of a few fully connected layers (put simply, a Multi-Layer Perceptron). They take the output from one type of encoder (say, a vision encoder) and transform it into a format that is suitable for processing by another type of encoder or decoder (like a language model).

-

Role of Linear Layers: Linear layers, or fully connected layers, are a fundamental component in neural networks. In VLMs, they are crucial for processing the output of vision encoders.

-

Processing Vision Encoder Output: After an image is processed through a vision encoder (like a CNN or a transformer-based vision model), the resulting feature representation needs to be adapted to be useful for language tasks. Linear layers can transform these vision features into a format that is compatible with the text modality.

-

Combining Modalities: In a VLM, after processing through adapters and linear layers, the transformed visual data can be combined with textual data. This combination typically occurs before or within the language model, allowing the VLM to generate responses or analyses that incorporate both visual and textual understanding.

-

End-to-End Training: In some advanced VLMs, the entire model, including vision encoders, linear layers, and language models, can be trained end-to-end. This approach allows the model to better learn how to integrate and interpret both visual and textual information.

-

Flexibility: Adapters offer flexibility in model training. They allow for fine-tuning a pre-trained model on a specific task without the need to retrain the entire model. This is particularly useful in VLMs where training from scratch is often computationally expensive.

- In summary, adapters and linear layers in VLMs serve as critical components for bridging the gap between visual and textual modalities, enabling these models to perform tasks that require an understanding of both images and text.

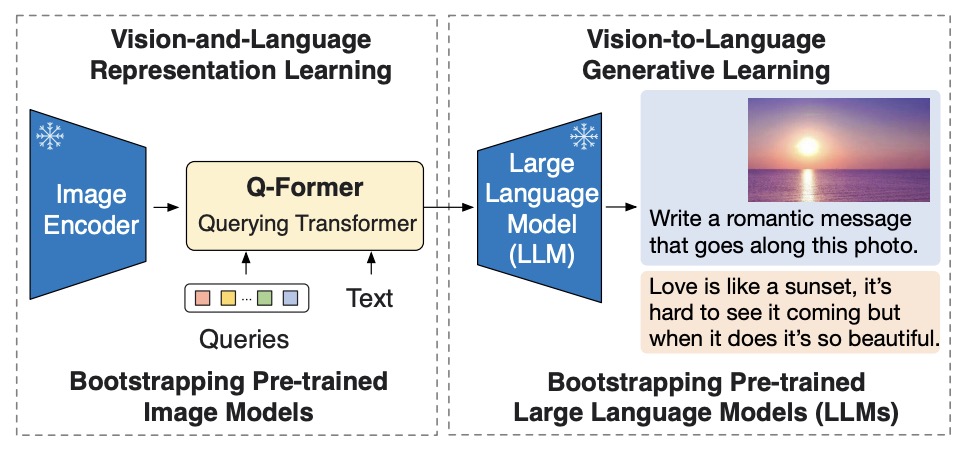

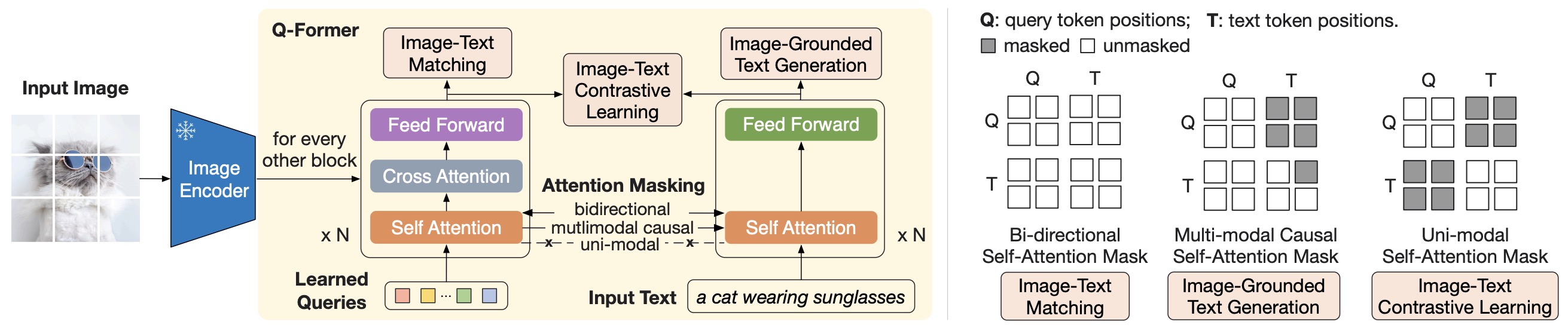

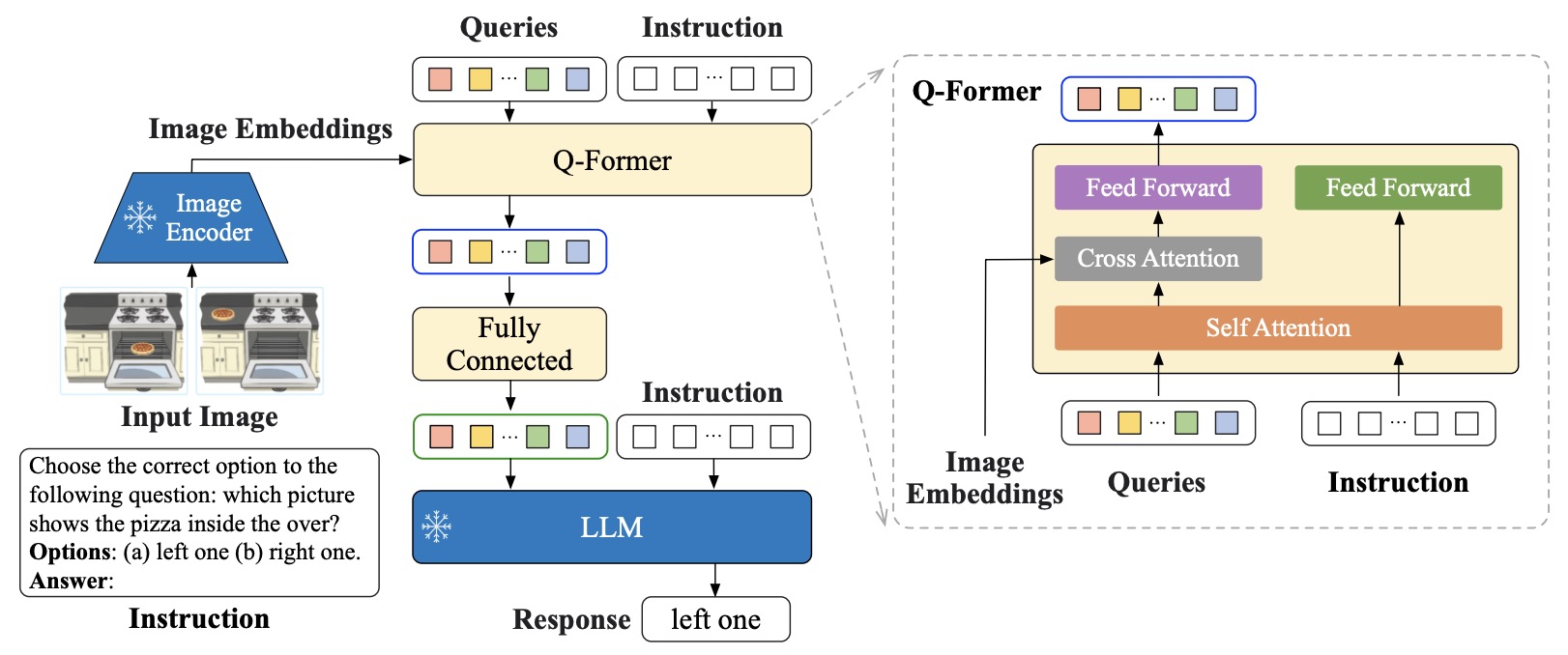

Q-Former

- The Querying Transformer (Q-Former) proposed in BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models is a critical component designed to carry out modality alignment and bridge the gap between a frozen image encoder and a frozen Large Language Model (LLM) in the BLIP-2 framework. Put simply, Q-Former is a trainable module designed to connect a frozen image encoder with a LLM.

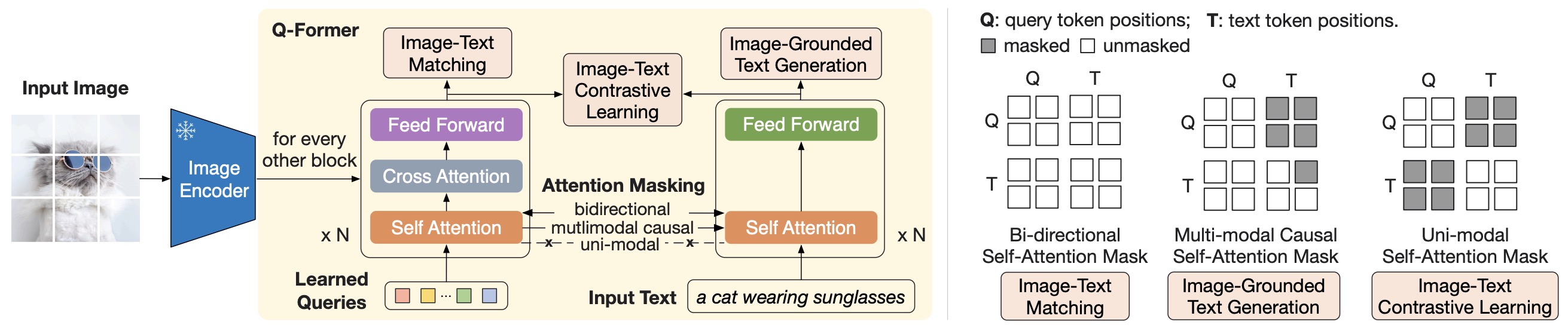

- It features two transformer submodules: an image transformer for visual feature extraction from the image encoder, and a text transformer that serves as both text encoder and decoder. The module uses learnable query embeddings for the image transformer, facilitating interactions through self-attention and cross-attention layers with the frozen image features. The queries interact with each other through self-attention layers, and interact with frozen image features through cross-attention layers (inserted every other transformer block). These queries additionally interact with text via the same self-attention layers. The Q-Former is initialized with BERTbase pre-trained weights, while its cross-attention layers are randomly initialized. It comprises 188M parameters and employs 32 queries, each with a dimension of 768. The output query representation is significantly smaller than the frozen image features, allowing the architecture to focus on extracting visual information most relevant to the text.

- Here’s an overview of its structure and role.

Internal Architecture of Q-Former

- Two Transformer Submodules: The Q-Former is composed of two main parts:

- Image Transformer: This submodule interacts with the frozen image encoder. It is responsible for extracting visual features.

- Text Transformer: This part can function as both a text encoder and a text decoder. It deals with processing and generating text.

- Learnable Query Embeddings: Q-Former utilizes a set number of learnable query embeddings. These queries:

- Interact with each other through self-attention layers.

- Engage with frozen image features through cross-attention layers, which are inserted in alternate transformer blocks.

- Can also interact with text through the same self-attention layers.

-

Self-Attention Masking Strategy: Depending on the pre-training task, different self-attention masks are applied to control interactions between queries and text.

- Initialization and Parameters: The Q-Former is initialized with pre-trained weights of BERTbase, but its cross-attention layers are randomly initialized. The Q-Former contains a total of 188 million parameters, with the queries being considered as model parameters.

Q-Former: A Visual Summary

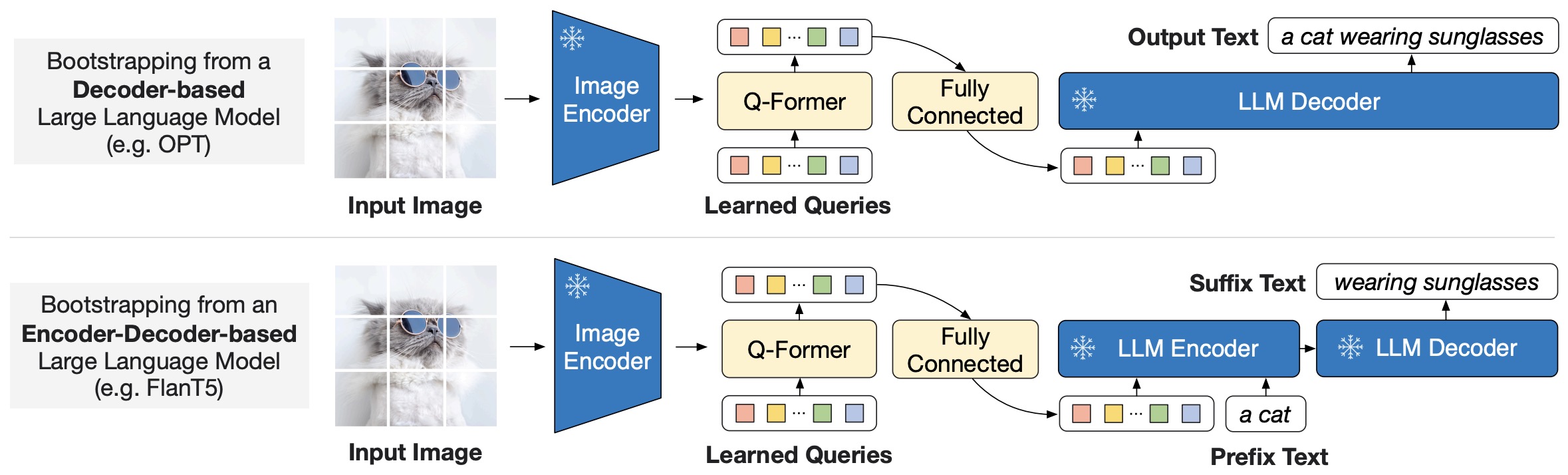

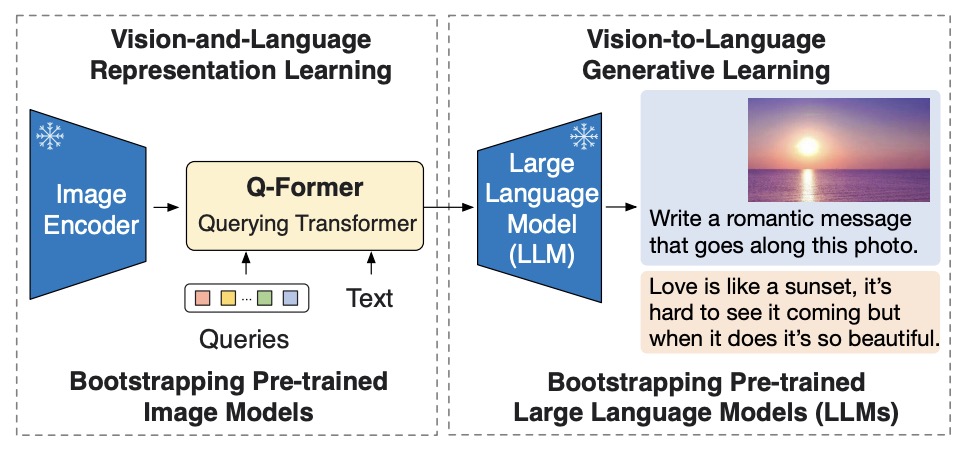

- The following figure from the paper shows an overview of BLIP-2’s framework. They pre-train a lightweight Querying Transformer following a two-stage strategy to bridge the modality gap. The first stage bootstraps vision-language representation learning from a frozen image encoder. The second stage bootstraps vision-to-language generative learning from a frozen LLM, which enables zero-shot instructed image-to-text generation.

- The following figure from the paper shows: (Left) Model architecture of Q-Former and BLIP-2’s first-stage vision-language representation learning objectives. They jointly optimize three objectives which enforce the queries (a set of learnable embeddings) to extract visual representation most relevant to the text. (Right) The self-attention masking strategy for each objective to control query-text interaction.

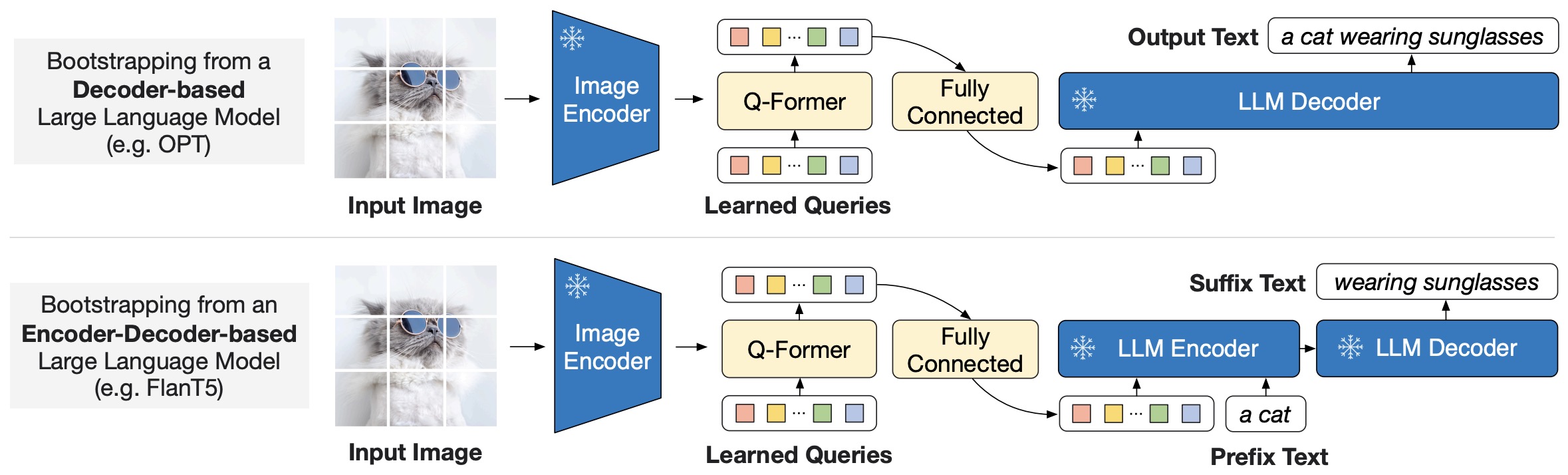

- The following figure from the paper shows BLIP-2’s second-stage vision-to-language generative pre-training, which bootstraps from frozen large language models (LLMs). (Top) Bootstrapping a decoder-based LLM (e.g., OPT). (Bottom) Bootstrapping an encoder-decoder-based LLM (e.g., FlanT5). The fully-connected layer adapts from the output dimension of the Q-Former to the input dimension of the chosen LLM.

Role of Q-Former

- Bridging Modalities: The primary function of the Q-Former is to serve as a trainable module that connects the visual information from the image encoder with the linguistic capabilities of the LLM.

- Feature Extraction and Interaction: It extracts a fixed number of output features from the image encoder, irrespective of the input image resolution, and enables interactions between these visual features and textual components.

- Adapting to Different Pre-training Tasks: Through its flexible architecture and self-attention masking strategy, the Q-Former can adapt to various pre-training tasks, effectively facilitating the integration of visual and textual data.

Summary

- To reiterate, the Q-Former in the BLIP-2 framework, as described in the document, comprises two transformer submodules - an image transformer and a text transformer. These submodules share self-attention layers. The image transformer interacts with the frozen image encoder for visual feature extraction, while the text transformer can function both as a text encoder and a text decoder. The Q-Former uses a set number of learnable query embeddings as input to the image transformer, which interacts with frozen image features through cross-attention layers (inserted in every other transformer block) and with the text through self-attention layers. The model applies different self-attention masks to control query-text interaction based on the pre-training task. The Q-Former is initialized with the pre-trained weights of BERTbase, and it contains a total of 188M parameters

- In summary, the Q-Former in the BLIP-2 framework plays a pivotal role in merging visual and textual information, making it a key element in enhancing the model’s ability to understand and generate contextually relevant responses in multimodal scenarios.

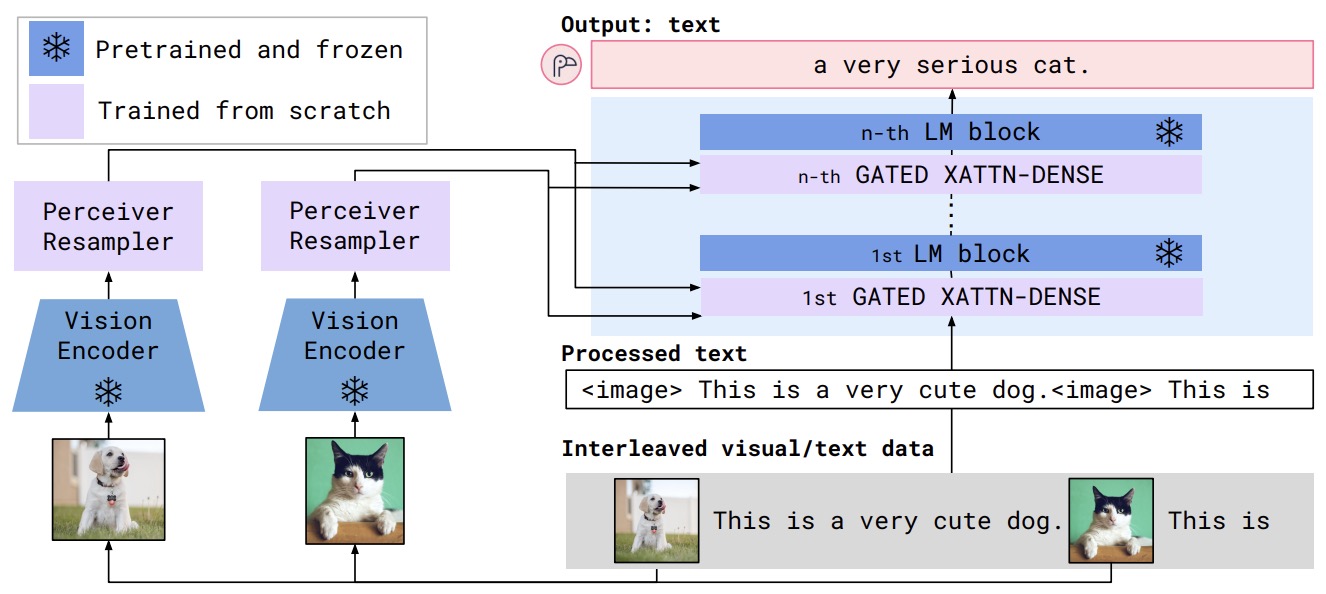

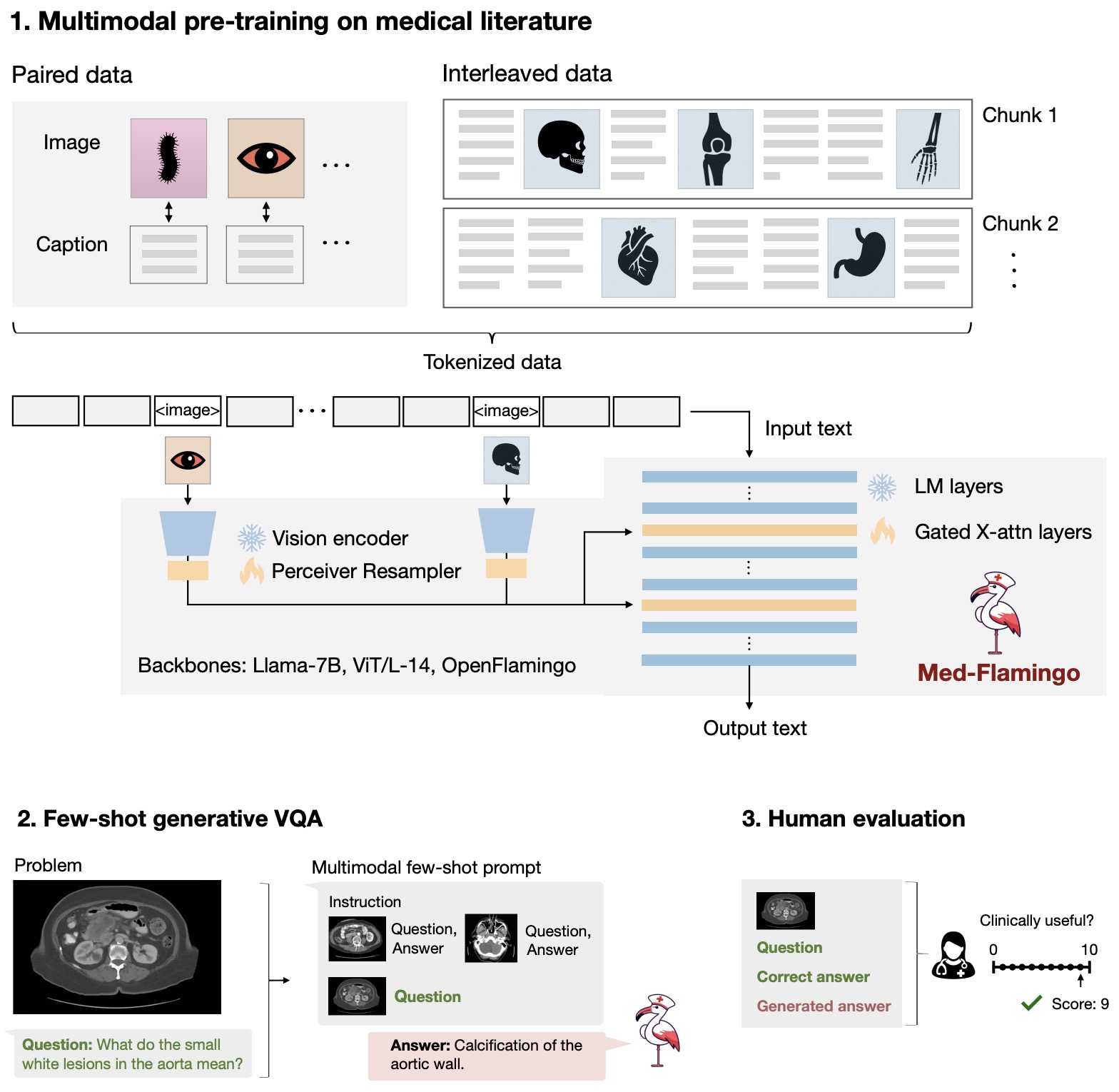

Perceiver Resampler

- The Perceiver Resampler, utilized in the Flamingo: a Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning is an integral component designed to efficiently bridge the gap between vision and language processing in the model. Here’s a breakdown of its composition and role:

Composition of Perceiver Resampler

- Function: The Perceiver Resampler’s primary function is to take a variable number of image or video features from the vision encoder and convert them into a fixed number of visual outputs.

- Output Generation: It produces 64 visual outputs regardless of the input size.

- Reducing Computational Complexity: By converting varying-size large feature maps into a few visual tokens, it significantly reduces the computational complexity involved in vision-text cross-attention.

- Latent Input Queries: Similar to the Perceiver and DETR models, it utilizes a predefined number of latent input queries. These queries are fed to a Transformer module.

- Cross-Attention Mechanism: The latent queries cross-attend to the visual features, facilitating the integration of visual information into the language processing workflow.

Flamingo: A Visual Summary

- The following figure from the paper shows the Flamingo architecture overview.

Role of Perceiver Resampler

- Connecting Vision and Language Models: It serves as a crucial link between the vision encoder and the frozen language model, enabling the model to process and integrate visual data efficiently.

- Efficiency and Performance: The Perceiver Resampler enhances the model’s ability to handle vision-language tasks more effectively compared to using a plain Transformer or a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP).

Summary

- To recap, the Perceiver Resampler is designed to convert varying-size large feature maps into a smaller number of visual tokens, thus reducing the computational complexity in vision-text cross-attention. It employs a set of latent input queries that interact with visual features through a Transformer, facilitating efficient integration of visual and textual data. In essence, the Perceiver Resampler plays a pivotal role in reducing the complexity of handling large visual data and efficiently integrating it with language processing, thereby enhancing the overall capability of the model in multimodal tasks.

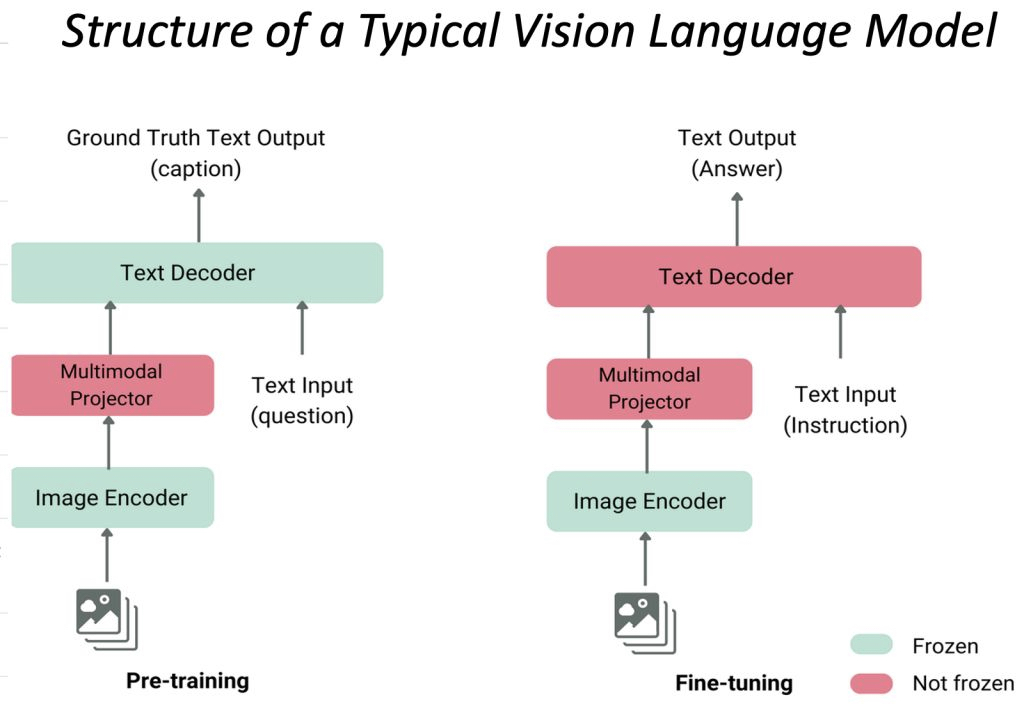

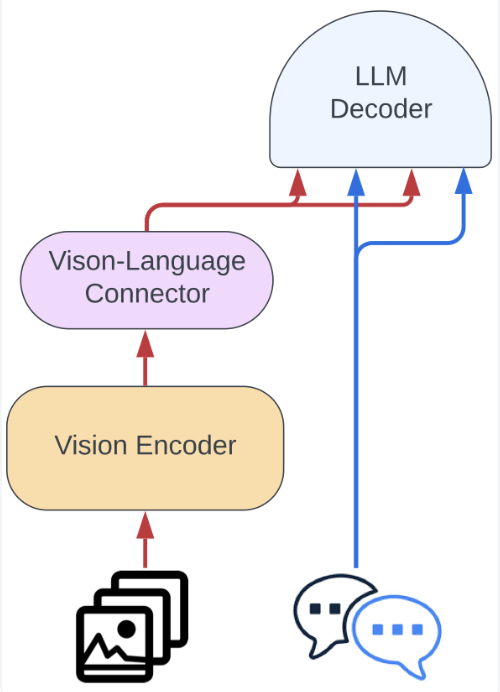

Training Process

- The diagram below illustrates the structure of a typical vision language model, depicting its components during different phases: pre-training and fine-tuning.

- Image Encoder:

- This component is responsible for processing the input image and encoding it into a feature-rich representation.

- In both the pre-training and fine-tuning phases, the Image Encoder is used to process the visual information.

- Multimodal Projector:

- This bridges the gap between the visual information encoded by the Image Encoder and the textual data processed or produced by the Text Decoder.

- It helps integrate or align the features from both modalities (text and image).

- Text Decoder (LLM):

- The Text Decoder generates text outputs based on the combined features provided by the Multimodal Projector.

- In the pre-training phase, the output is typically a caption that describes the image (Ground Truth Text Output), i.e., the data is in the form of

(image, text)pairs. In the fine-tuning phase, the output is an answer or a response to an instruction (Text Output).

- Text Input:

- In pre-training, the model might receive a question or some form of textual prompt to guide the generation of the image caption.

- In fine-tuning, the input text could be an instruction or specific question that guides the model to provide a more focused or contextual answer.

- Frozen vs. Not Frozen Components:

- The diagram indicates that certain parts of the model may be frozen (not updated) during the fine-tuning phase. Typically, this would be the Image Encoder to preserve the learned visual features.

- While the Multimodal Projector is fine-tuned during both the pre-training and fine-tuning phases, the Text Decoder (LLM) is fine-tuned only during the fine-tuning phase (and kept frozen during pre-training).

- This structure enables the model to leverage both visual and textual information effectively, adapting to various tasks by fine-tuning specific components.

Fine-Tuning Process

- When fine-tuning a VLM, the decision of which layers to fine-tune is guided by the model’s architecture and the specific objectives of the fine-tuning task. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

Vision Encoder Layers

- Role: These layers process and encode the visual input, such as images. They capture features from the visual data that are then used by the model to understand and integrate with text.

- When to Fine-Tune: Fine-tuning these layers is particularly beneficial if the visual data domain of your task differs from the domain on which the model was originally pre-trained. For example, if the model was pre-trained on general image datasets but your task involves medical images or satellite imagery, fine-tuning these layers can help the model better adapt to the new visual domain.

Language Model (LLM) Layers

- Role: These layers are responsible for processing and encoding textual input, such as captions or descriptions. They interpret and generate text based on the information received from the vision encoder and projection layers.

- When to Fine-Tune: Fine-tuning the LLM layers is crucial when the textual data in your task contains characteristics that differ significantly from the pre-training data. For instance, if your task involves domain-specific language, such as technical jargon or legal terminology, fine-tuning the LLM layers will enable the model to generate and understand text that is more accurate and relevant to that specific domain.

Projection/Cross-Attention Layers

- Role: In many VLM architectures, projection/cross-attention layers allow the model to integrate and align visual and textual inputs, facilitating the interaction between these modalities.

- When to Fine-Tune: Fine-tuning the projection layers is particularly important for tasks that require a strong correlation between visual and textual data, such as visual question answering, image captioning, or tasks involving multimodal reasoning. These layers help the model better understand and relate the visual content to the corresponding text, improving overall performance on such tasks.

Common Fine-Tuning Strategies

- Fine-Tuning the Entire Model: This involves fine-tuning all layers (vision encoder, LLM, and projection layers). While this approach is resource-intensive, it allows the model to fully adapt to the new task, making it the most comprehensive strategy.

- Partial Fine-Tuning: In this approach, some layers, often the lower layers, are kept frozen to retain the general features learned during pre-training, while others, typically the higher layers or projection layers, are fine-tuned. This reduces computational costs and is effective when the new task is similar to the original pre-training tasks.

- Adapter-Based Fine-Tuning: Instead of fine-tuning the main layers directly, small adapter layers are inserted into the model, and only these adapters are fine-tuned. This is a parameter-efficient approach that allows for task-specific tuning without modifying the original model weights extensively.

Use of LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation)

- LoRA Application: LoRA can be applied to any of these layers (Vision Encoder, LLM, or Projection) to introduce efficient, lightweight fine-tuning. By adding trainable low-rank matrices to the existing model parameters, LoRA allows for fine-tuning with minimal additional computational overhead. This approach is particularly useful in scenarios where full model fine-tuning is impractical due to resource constraints.

Summary

In summary, whether you fine-tune the Vision Encoder layers, LLM layers, or Projection layers depends on the nature of your task:

- Fine-tune Vision Encoder Layers for tasks involving new or different visual domains.

- Fine-tune LLM Layers when dealing with domain-specific textual data.

- Fine-tune Projection Layers for tasks that require strong integration of visual and textual information.

- LoRA can be effectively used to fine-tune these layers in a resource-efficient manner, enabling the model to adapt to new tasks with minimal changes to its original structure.

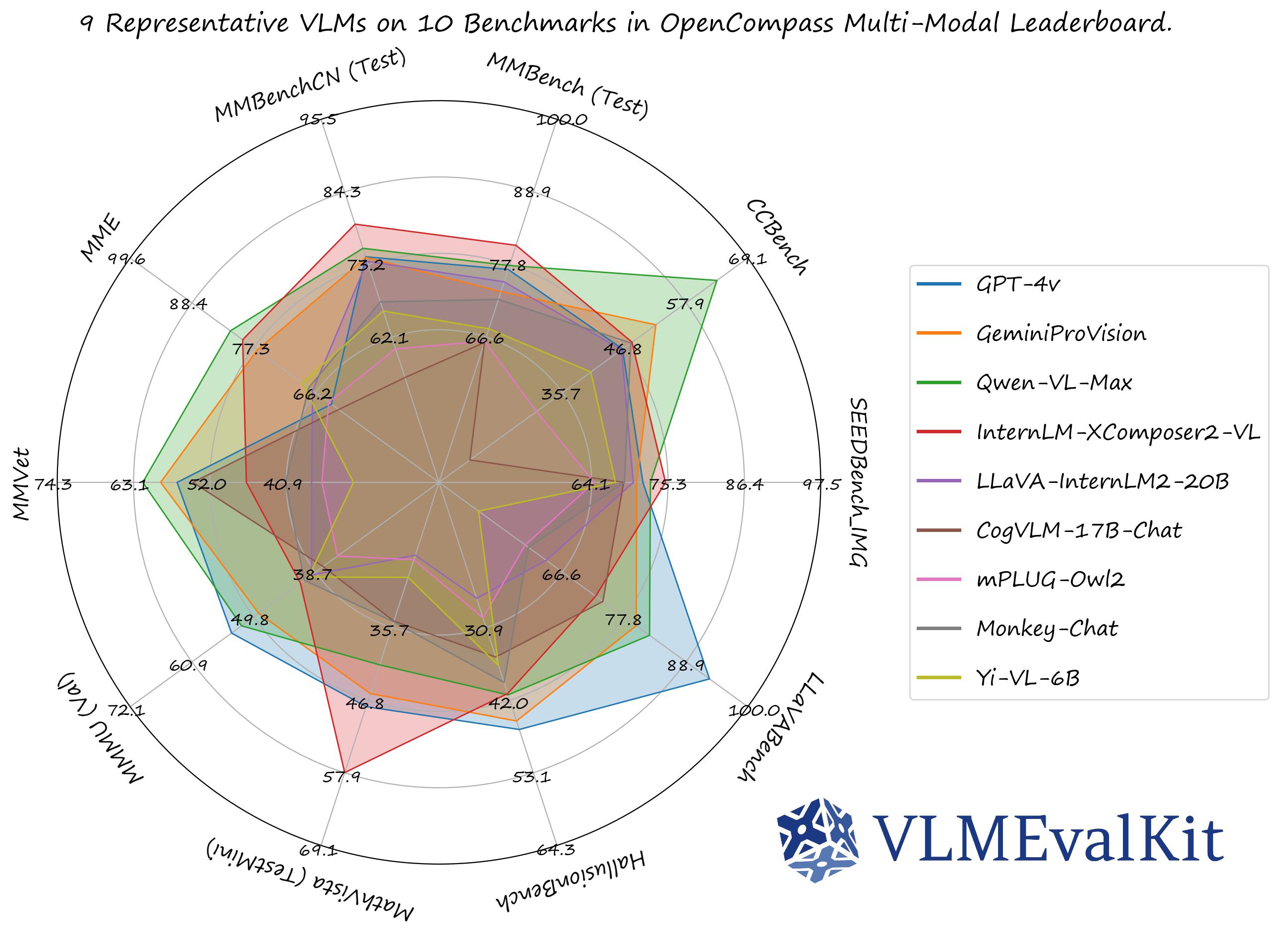

Leaderboards

🤗 Open VLM Leaderboard

- Based on VLMEvalKit: A Toolkit for Evaluating Large Vision-Language Models which is an open-source evaluation toolkit for VLMs.

- As of this writing, the Open VLM Leaderboard covers 54 different VLMs (including GPT-4V, Gemini, QwenVL-Plus, LLaVA, etc.) and 22 different multi-modal benchmarks.

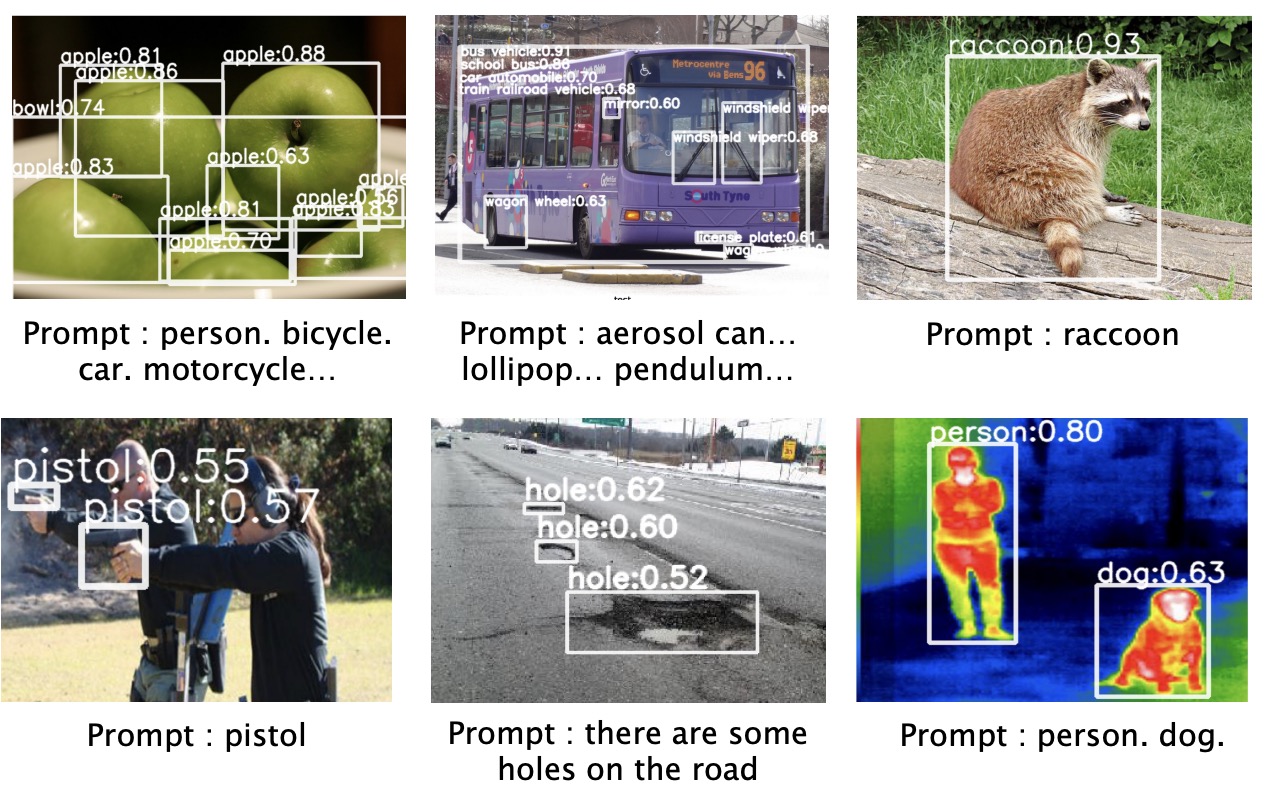

🤗 Open Object Detection Leaderboard

- The 🤗 Open Object Detection Leaderboard aims to track, rank and evaluate vision models available in the hub designed to detect objects in images.

Popular VLMs

VLMs for Generation

GPT-4V

- GPT-4 with vision (GPT-4V) enables users to instruct GPT-4 to analyze image inputs provided by the user.

- In the GPT-4V system card, OpenAI has analyzed the safety properties of GPT-4V.

LLaVA

- LLaVA is the most popular open-source multimodal framework.

- Proposed in Visual Instruction Tuning by Liu et al. from UW-Madison, Microsoft Research, and Columbia University.

- Instruction tuning large language models (LLMs) using machine-generated instruction-following data has improved zero-shot capabilities on new tasks, but the idea is less explored in the multimodal field.

- The paper presents the first attempt to use language-only GPT-4 to generate multimodal language-image instruction-following data. By instruction tuning on such generated data, they introduce Large Language-and-Vision Assistant (LLaVA), an end-to-end trained large multimodal model that connects a vision encoder and LLM for general-purpose visual and language understanding.

- LLaVA is a minimal extension of the LLaMA series which conditions the model on visual inputs besides just text. The model leverages a pre-trained CLIP’s vision encoder to provide image features to the LLM, with a lightweight projection module in between.

- The model is first pre-trained on image-text pairs to align the features of the LLM and the CLIP encoder, keeping both frozen, and only training the projection layer. Next, the entire model is fine-tuned end-to-end, only keeping CLIP frozen, on visual instruction data to turn it into a multimodal chatbot.

- Their early experiments show that LLaVA demonstrates impressive multimodel chat abilities, sometimes exhibiting the behaviors of multimodal GPT-4 on unseen images/instructions, and yields a 85.1% relative score compared with GPT-4 on a synthetic multimodal instruction-following dataset. When fine-tuned on Science QA, the synergy of LLaVA and GPT-4 achieves a new state-of-the-art accuracy of 92.53%.

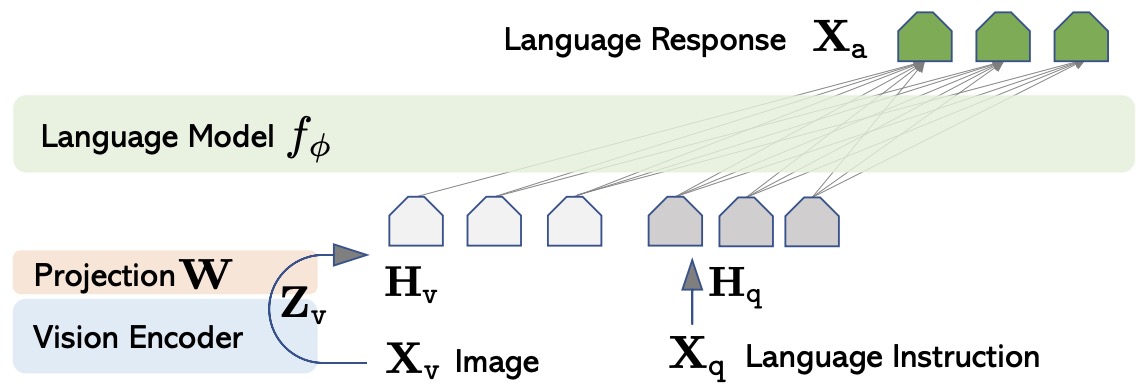

- The following figure from the paper shows the LLaVA network architecture.

- Project page; Demo; Code.

Frozen

- When trained at sufficient scale, auto-regressive language models exhibit the notable ability to learn a new language task after being prompted with just a few examples.

- Proposed in Multimodal Few-Shot Learning with Frozen Language Models, this paper by Tsimpoukelli et al. from DeepMind in NeurIPS 2021 presents Frozen – a simple, yet effective, approach for transferring this few-shot learning ability to a multimodal setting (vision and language).

- Using aligned image and caption data, they train a vision encoder to represent each image as a sequence of continuous embeddings, such that a pre-trained, frozen language model prompted with this prefix generates the appropriate caption.

- The resulting system is a multimodal few-shot learner, with the surprising ability to learn a variety of new tasks when conditioned on examples, represented as a sequence of multiple interleaved image and text embeddings.

- They demonstrate that it can rapidly learn words for new objects and novel visual categories, do visual question-answering with only a handful of examples, and make use of outside knowledge, by measuring a single model on a variety of established and new benchmarks.

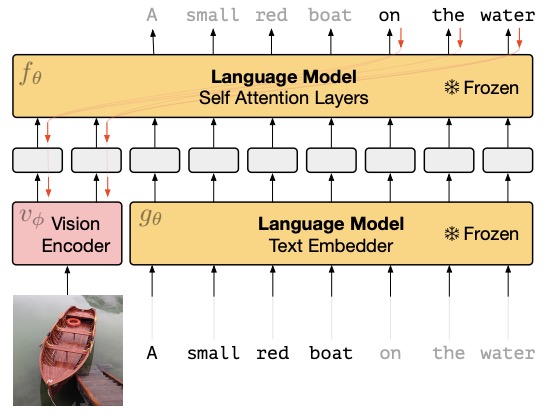

- The following figure from the paper shows that gradients through a frozen language model’s self attention layers are used to train the vision encoder:

- Code.

Flamingo

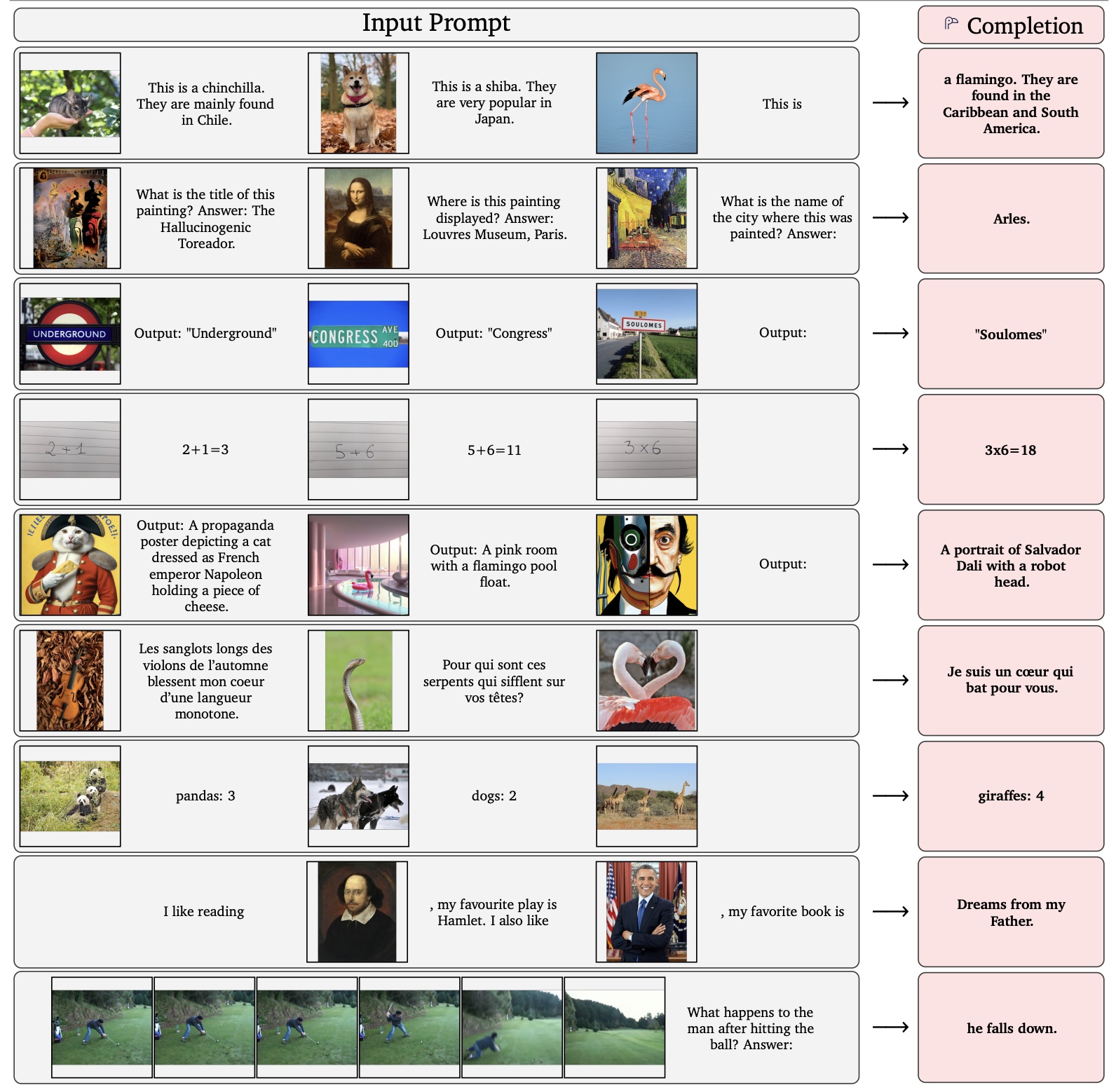

- Introduced in Flamingo: a Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning, Flamingo models include key architectural innovations to: (i) bridge powerful pretrained vision-only and language-only models, (ii) handle sequences of arbitrarily interleaved visual and textual data, and (iii) seamlessly ingest images or videos as inputs.

- The key ideas behind Flamingo are:

- Interleave cross-attention layers with language-only self-attention layers (frozen).

- Perceiver-based architecture that transforms the input sequence data (videos) into a fixed number of visual tokens.

- Large-scale (web) multi-modal data by scraping webpages which has inter-leaved text and images.

- Thanks to their flexibility, Flamingo models can be trained on large-scale multimodal web corpora containing arbitrarily interleaved text and images, which is key to endow them with in-context few-shot learning capabilities.

- They perform a thorough evaluation of the proposed Flamingo models, exploring and measuring their ability to rapidly adapt to a variety of image and video understanding benchmarks. These include open-ended tasks such as visual question-answering, where the model is prompted with a question which it has to answer, captioning tasks, which evaluate the ability to describe a scene or an event, and close-ended tasks such as multiple choice visual question-answering.

- For tasks lying anywhere on this spectrum, they demonstrate that a single Flamingo model can achieve a new state of the art for few-shot learning, simply by prompting the model with task-specific examples. On many of these benchmarks, Flamingo actually surpasses the performance of models that are fine-tuned on thousands of times more task-specific data.

OpenFlamingo

- An open source version of DeepMind’s Flamingo model! They provide a PyTorch implementation for training and evaluating OpenFlamingo models as well as an initial OpenFlamingo 9B model trained on a new Multimodal C4 dataset.

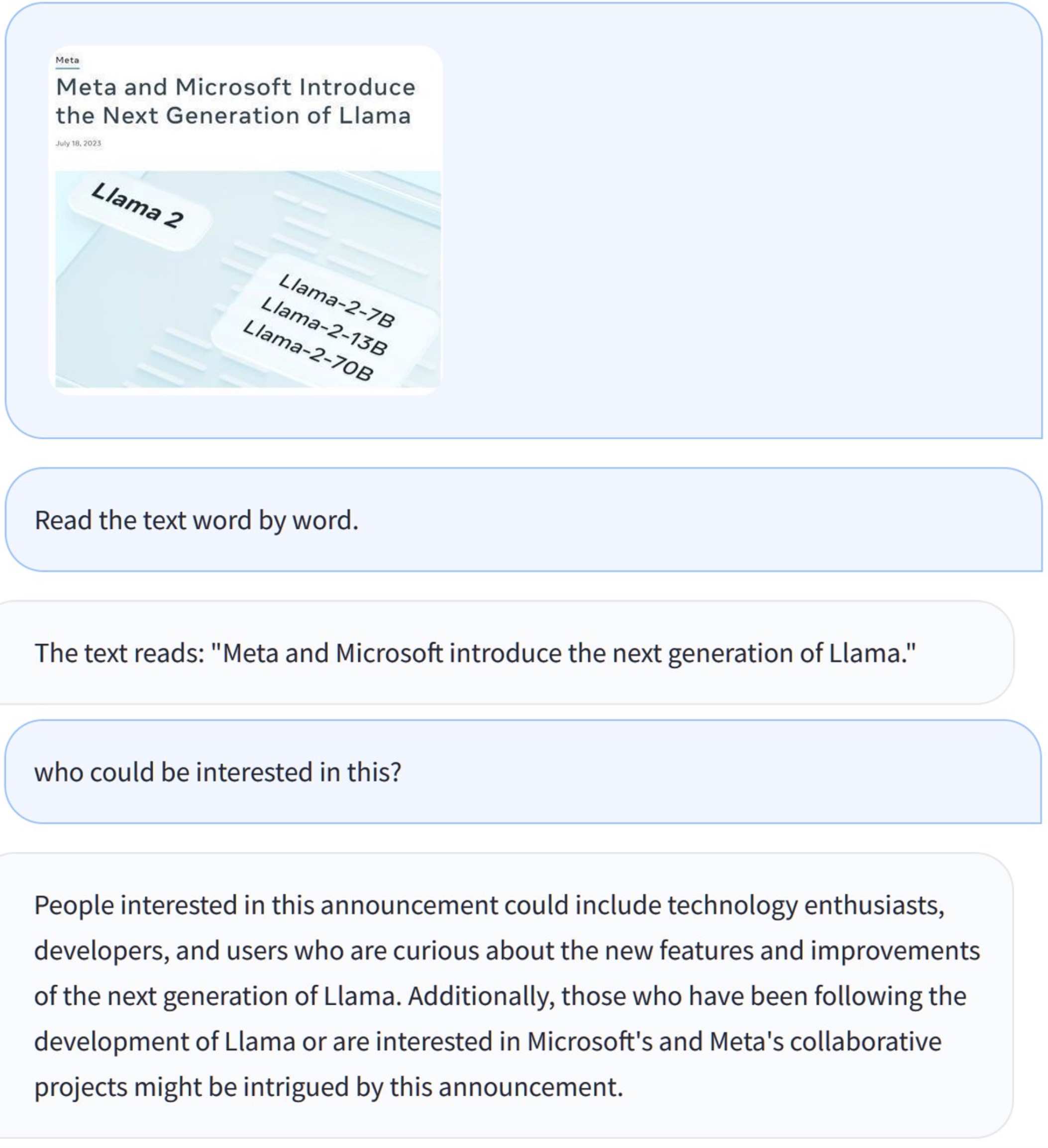

Idefics

- IDEFICS (Image-aware Decoder Enhanced à la Flamingo with Interleaved Cross-attentionS) is an open-access reproduction of Flamingo, a closed-source visual language model developed by Deepmind. IDEFICS is an 80 billion parameter model of DeepMind’s Flamingo VLM model. Like GPT-4, the multimodal model accepts arbitrary sequences of image and text inputs and produces text outputs. IDEFICS is built solely on publicly available data and models.

- The model can answer questions about images, describe visual contents, create stories grounded on multiple images, or simply behave as a pure language model without visual inputs.

- IDEFICS is on par with the original closed-source model on various image-text benchmarks, including visual question answering (open-ended and multiple choice), image captioning, and image classification when evaluated with in-context few-shot learning. It comes into two variants: a large 80 billion parameters version and a 9 billion parameters version.

- HuggingFace has also fine-tuned the base models on a mixture of supervised and instruction fine-tuning datasets, which boosts the downstream performance while making the models more usable in conversational settings: idefics-80b-instruct and idefics-9b-instruct.

- The following screenshot is an example of interaction with the instructed model:

Knowledge sharing memo for IDEFICS, an open-source reproduction of Flamingo

- Notes/lessons by HuggingFace on training IDEFICS. They highlight the mistakes they’ve made and remaining open questions. Using an auxiliary Z-loss, Atlas for data filtering, and BF16 loss values were particularly enlightening.

- Related: Older knowledge memo which focused on lessons learned from stabilizing training at medium scale.

Idefics2: A Powerful 8B Vision-Language Model for the Community

- This article introduces Idefics2, a general multimodal model capable of processing arbitrary sequences of texts and images to generate text responses. It excels in various tasks such as answering questions about images, describing visual content, creating stories grounded in multiple images, extracting information from documents, and performing basic arithmetic operations. Idefics2 is an improved version of Idefics1, featuring 8 billion parameters, an open Apache 2.0 license, and enhanced OCR capabilities, positioning it as a strong foundation for the multimodality community.

- Idefics2’s architecture integrates images and text more efficiently than Idefics1 by moving away from gated cross-attentions and simplifying the integration of visual features into the language backbone. Images are processed through a vision encoder followed by Perceiver pooling and an MLP modality projection, which are then concatenated with text embeddings as shown in the figure below. This approach enables the model to handle images in their native resolutions and aspect ratios, eliminating the need for resizing.

- Training data for Idefics2 included a mixture of openly available datasets such as Wikipedia, OBELICS, LAION-COCO, PDFA, IDL, Rendered-text, and WebSight. Additionally, Idefics2 was fine-tuned using “The Cauldron,” an open compilation of 50 manually-curated datasets formatted for multi-turn conversations. This comprehensive dataset compilation addresses the challenge of scattered and disparate task-oriented data formats in the community.

- Significant implementation details include the use of sub-image splitting to handle large-resolution images, following strategies from SPHINX and LLaVa-NeXT. The model’s OCR capabilities were significantly enhanced by integrating data requiring transcription of text in images and documents. Furthermore, Idefics2 demonstrates superior performance on various Visual Question Answering benchmarks, competing with much larger models like LLava-Next-34B and MM1-30B-chat.

- The article provides a code sample for users to get started with Idefics2 using the Hugging Face Hub. The sample illustrates how to load images, create inputs, and generate text responses using the model. The fine-tuning colab offered by the authors is intended to help users improve Idefics2 for specific use cases.

- Overall, Idefics2 represents a significant advancement in multimodal AI, offering improved performance, flexibility, and accessibility for a wide range of applications.

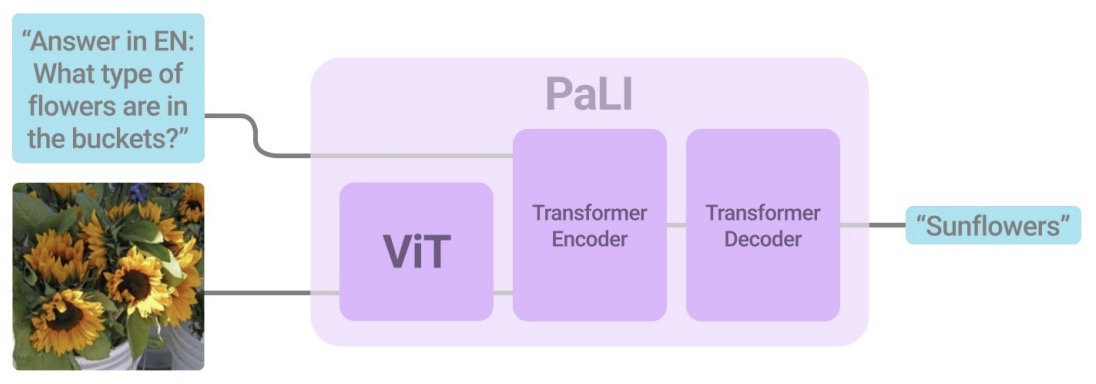

PaLI

- Introduced in PaLI: Scaling Language-Image Learning in 100+ Languages.

- Effective scaling and a flexible task interface enable large language models to excel at many tasks.

- This paper by Chen et al. from Google Research in ICLR 2023 presents PaLI (Pathways Language and Image model), a model that extends this approach to the joint modeling of language and vision.

- PaLI generates text based on visual and textual inputs, and with this interface performs many vision, language, and multimodal tasks, in many languages.

- To train PaLI, they make use of large pre-trained encoder-decoder language models and Vision Transformers (ViTs). This allows them to capitalize on their existing capabilities and leverage the substantial cost of training them. They find that joint scaling of the vision and language components is important.

- Since existing Transformers for language are much larger than their vision counterparts, we train a large, 4-billion parameter ViT (ViT-e) to quantify the benefits from even larger-capacity vision models.

- To train PaLI, they create a large multilingual mix of pretraining tasks, based on a new image-text training set containing 10B images and texts in over 100 languages. PaLI achieves state-of-the-art in multiple vision and language tasks (such as captioning, visual question-answering, scene-text understanding), while retaining a simple, modular, and scalable design.

- The PaLI main architecture is simple and scalable. It uses an encoder-decoder Transformer model, with a large-capacity ViT component for image processing.

- Code.

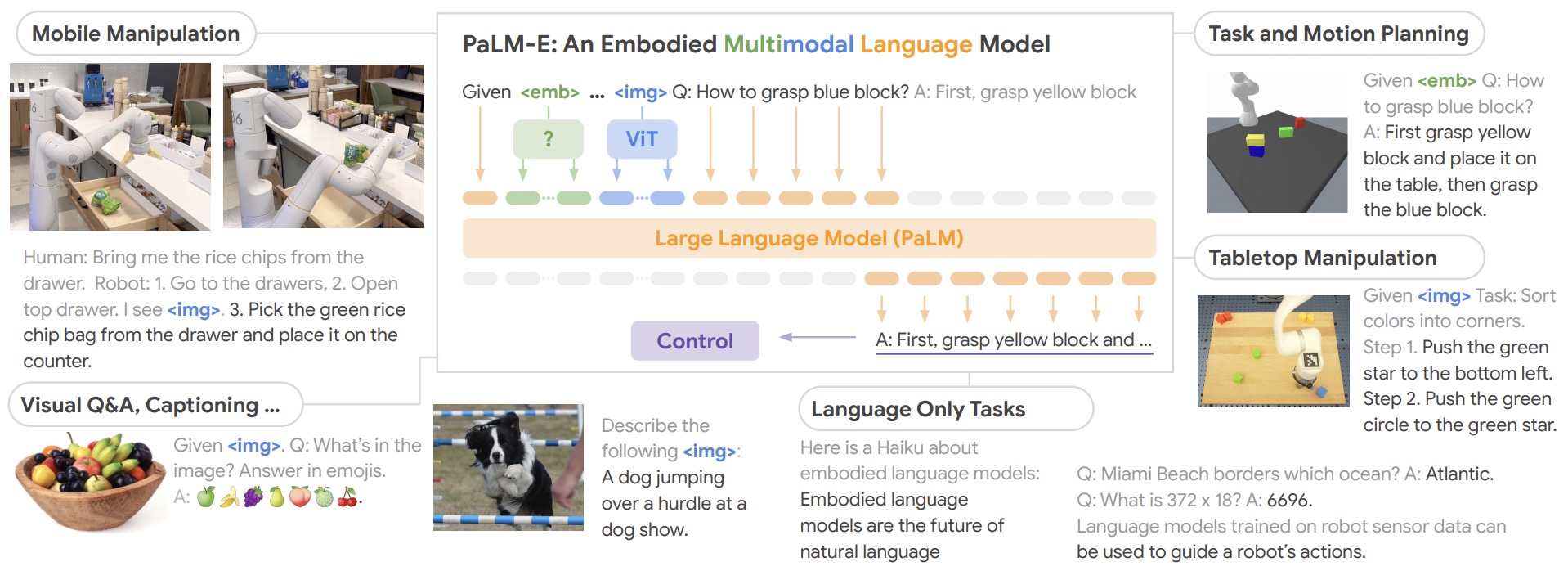

PaLM-E

- Introduced in PaLM-E: An Embodied Multimodal Language Model.

- Large language models have been demonstrated to perform complex tasks. However, enabling general inference in the real world, e.g. for robotics problems, raises the challenge of grounding.

- This paper by Driess from Google, TU Berlin, and Google Research proposes PaLM-E, an embodied language models to directly incorporate real-world continuous sensor modalities into language models and thereby establish the link between words and percepts. Input to their embodied language model are multi-modal sentences that interleave visual, continuous state estimation, and textual input encodings.

- They train these encodings end-to-end, in conjunction with a pre-trained large language model, for multiple embodied tasks, including sequential robotic manipulation planning, visual question answering, and captioning.

- Their evaluations show that PaLM-E, a single large embodied multimodal model, can address a variety of embodied reasoning tasks, from a variety of observation modalities, on multiple embodiments, and further, exhibits positive transfer: the model benefits from diverse joint training across internet-scale language, vision, and visual-language domains.

- Their largest model, PaLM-E-562B with 562B parameters, in addition to being trained on robotics tasks, is a visual-language generalist with state-of-the-art performance on OK-VQA, and retains generalist language capabilities with increasing scale.

- The following figures from the paper shows PaLM-E, a single general-purpose multimodal language model for embodied reasoning tasks, visual-language tasks, and language tasks. - PaLM-E transfers knowledge from visual-language domains into embodied reasoning – from robot planning in environments with complex dynamics and physical constraints, to answering questions about the observable world. PaLM-E operates on multimodal sentences, i.e. sequences of tokens where inputs from arbitrary modalities (e.g. images, neural 3D representations, or states, in green and blue) are inserted alongside text tokens (in orange) as input to an LLM, trained end-to-end.

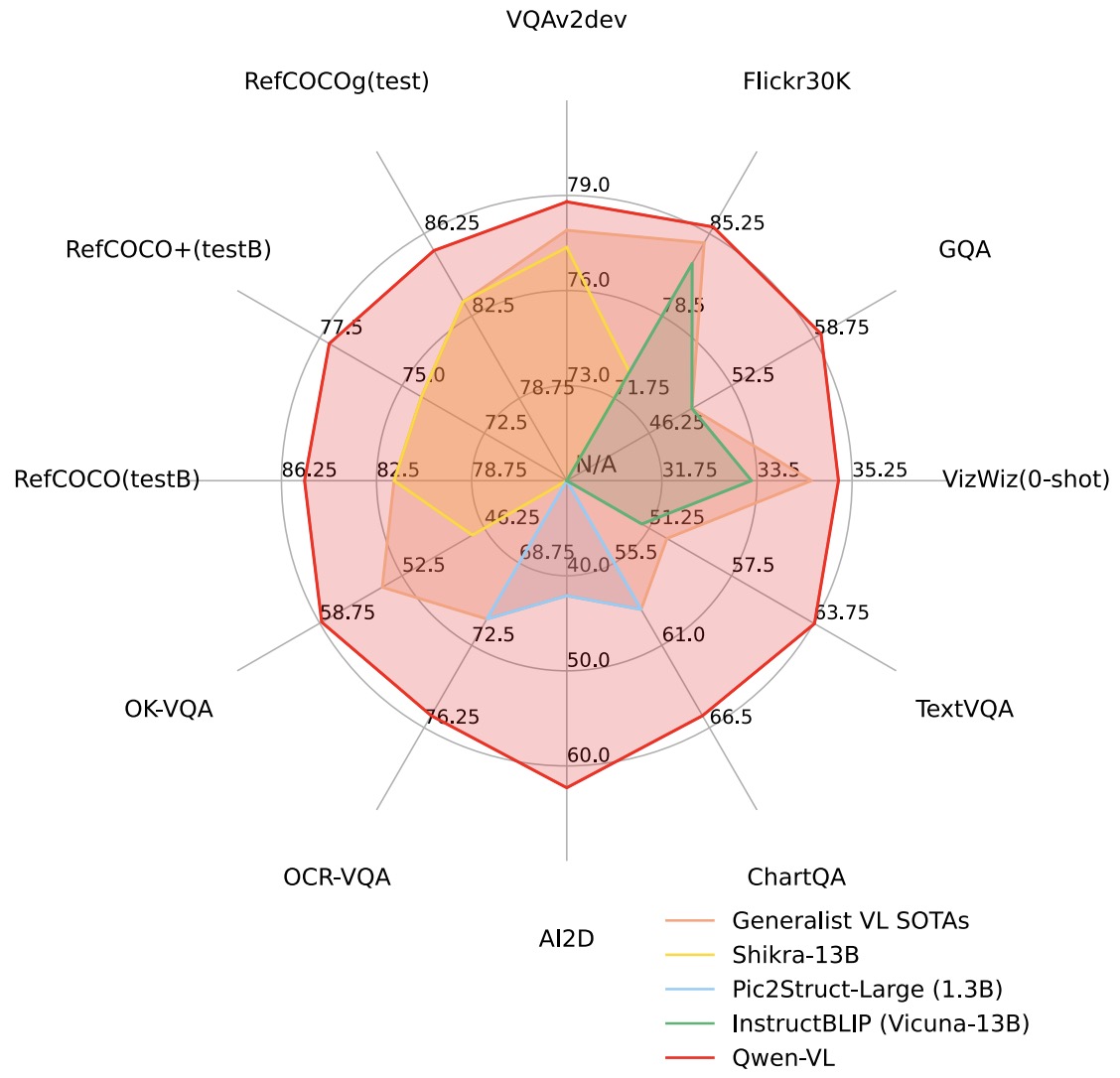

Qwen-VL

- Introduced in Qwen-VL: A Frontier Large Vision-Language Model with Versatile Abilities, the Qwen-VL series are a set of large-scale vision-language models designed to perceive and understand both text and images. Comprising Qwen-VL and Qwen-VL-Chat, these models exhibit remarkable performance in tasks like image captioning, question answering, visual localization, and flexible interaction.

- The evaluation covers a wide range of tasks including zero-shot captioning, visual or document visual question answering, and grounding. We demonstrate the Qwen-VL outperforms existing Large Vision Language Models (LVLMs).

- They present their architecture, training, capabilities, and performance, highlighting their contributions to advancing multimodal artificial intelligence.

- The following figure from the paper shows that Qwen-VL achieves state-of-the-art performance on a broad range of tasks compared with other generalist models.

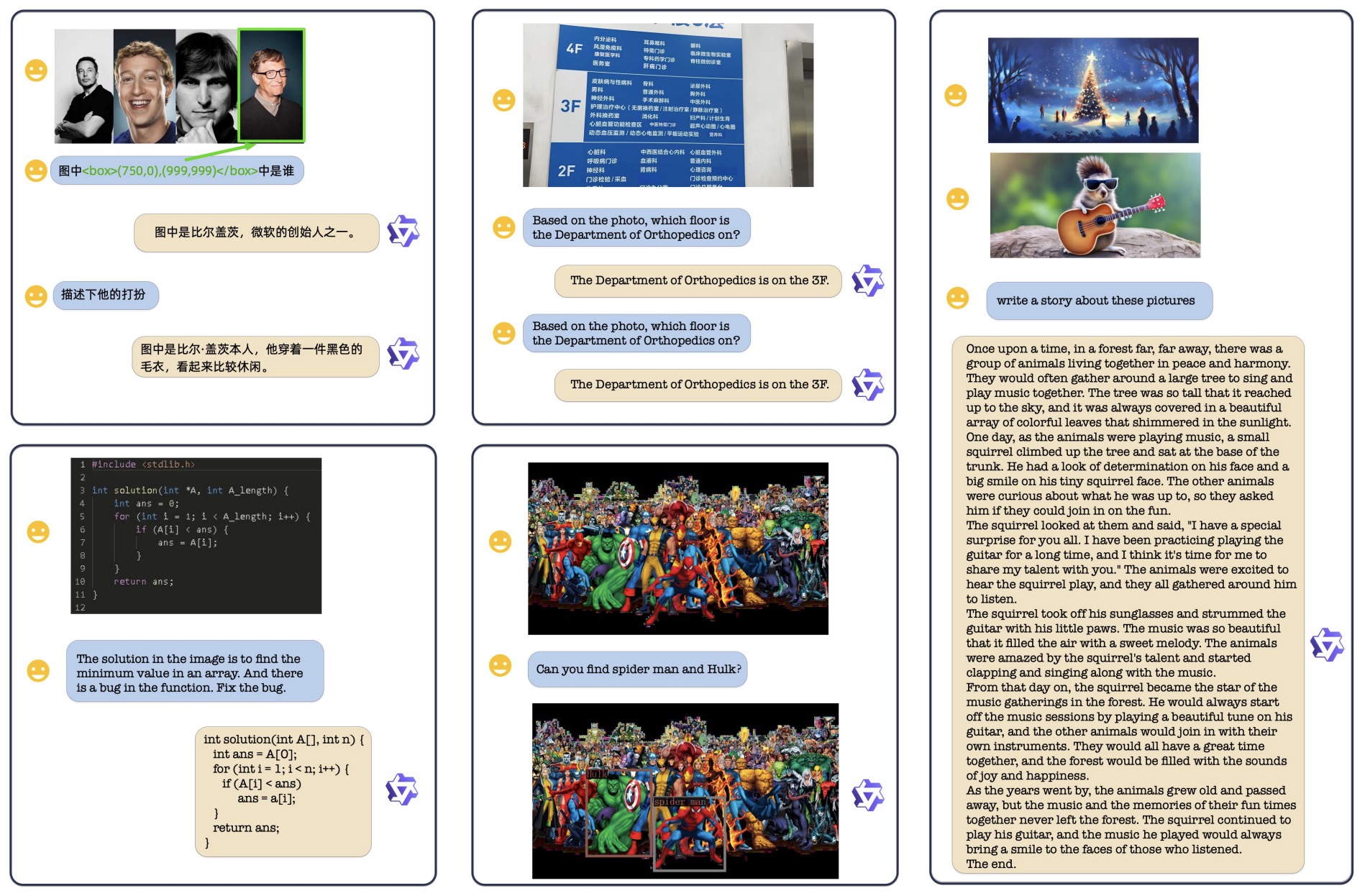

- The following figure from the paper shows some qualitative examples generated by Qwen-VL-Chat. Qwen-VL-Chat supports multiple image inputs, multi-round dialogue, multilingual conversation, and localization ability.

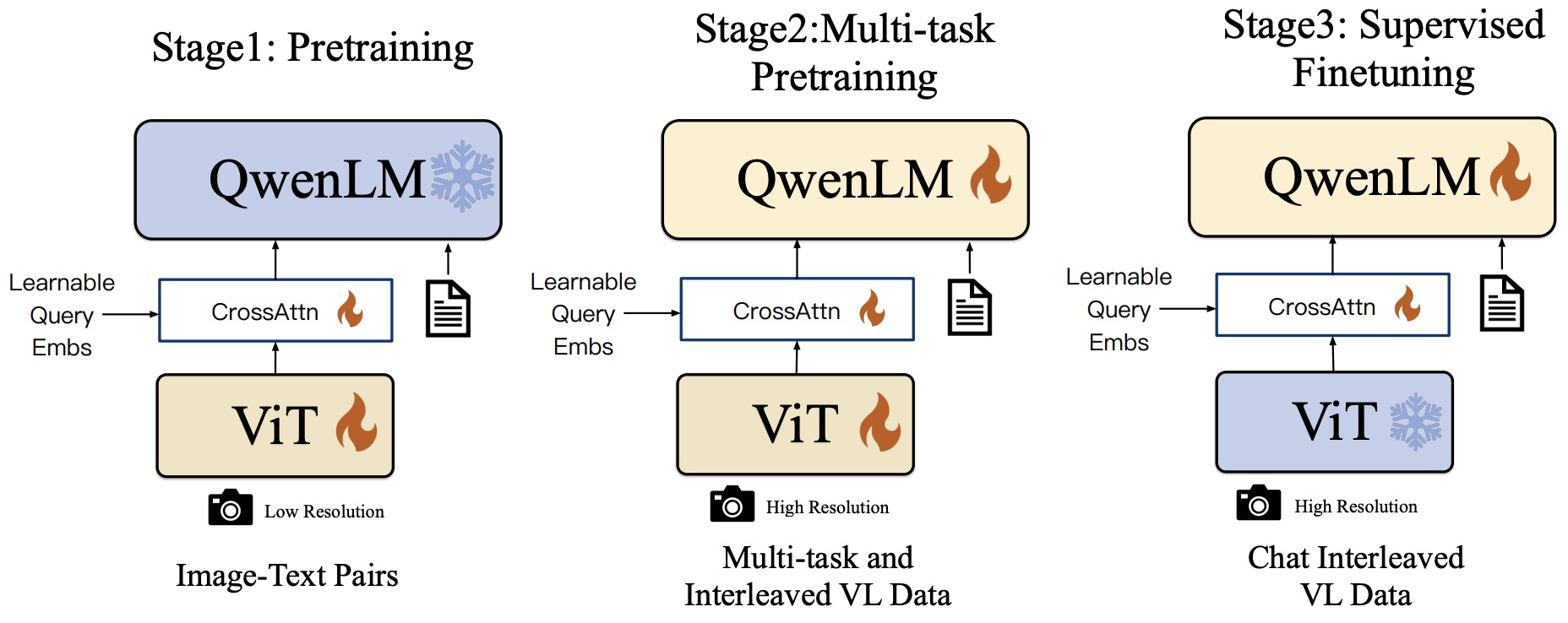

- The following figure from the paper shows the training pipeline of the Qwen-VL series.

QwenVL-Plus and Max

- Qwen-VL-Plus and Max are upgraded versions of Qwen-VL, developed by Alibaba Cloud.

Fuyu-8B

- Fuyu-8B is a multi-modal text and image transformer trained by Adept AI.

- Fuyu-8B is a small version of the multimodal model that powers our product. The model is available on HuggingFace. Fuyu-8B is exciting because:

- It has a much simpler architecture and training procedure than other multi-modal models, which makes it easier to understand, scale, and deploy.

- It’s designed from the ground up for digital agents, so it can support arbitrary image resolutions, answer questions about graphs and diagrams, answer UI-based questions, and do fine-grained localization on screen images.

- It’s fast – we can get responses for large images in less than 100 milliseconds.

- Despite being optimized for Adept’s use-case, it performs well at standard image understanding benchmarks such as visual question-answering and natural-image-captioning.

- Architecturally, Fuyu is a vanilla decoder-only transformer - there is no image encoder. Image patches are instead linearly projected into the first layer of the transformer, bypassing the embedding lookup. They simply treat the transformer decoder like an image transformer (albeit with no pooling and causal attention). See the below diagram for more details.

- This simplification allows us to support arbitrary image resolutions. To accomplish this, they treat the sequence of image tokens like the sequence of text tokens. they remove image-specific position embeddings and feed in as many image tokens as necessary in raster-scan order. To tell the model when a line has broken, they simply use a special image-newline character. The model can use its existing position embeddings to reason about different image sizes, and they can use images of arbitrary size at training time, removing the need for separate high and low-resolution training stages.

- Blog.

SPHINX

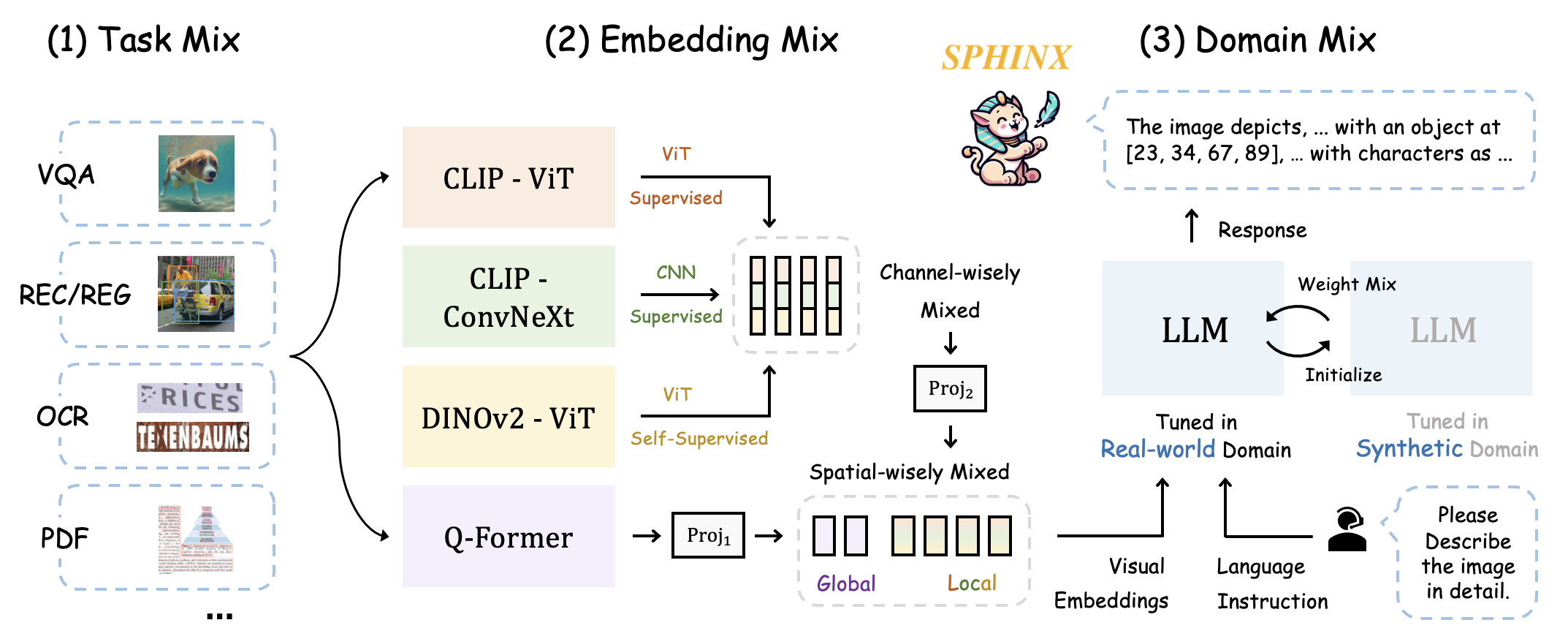

- SPHINX is a versatile multi-modal large language model (MLLM) with a mixer of training tasks, data domains, and visual embeddings.

- Task Mix: For all-purpose capabilities, they mix a variety of vision-language tasks for mutual improvement: VQA, REC, REG, OCR, etc.

- Embedding Mix: They capture robust visual representations by fusing distinct visual architectures, pre-training, and granularity.

- Domain Mix: For data from real-world and synthetic domains, they mix the weights of two domain-specific models for complementarity.

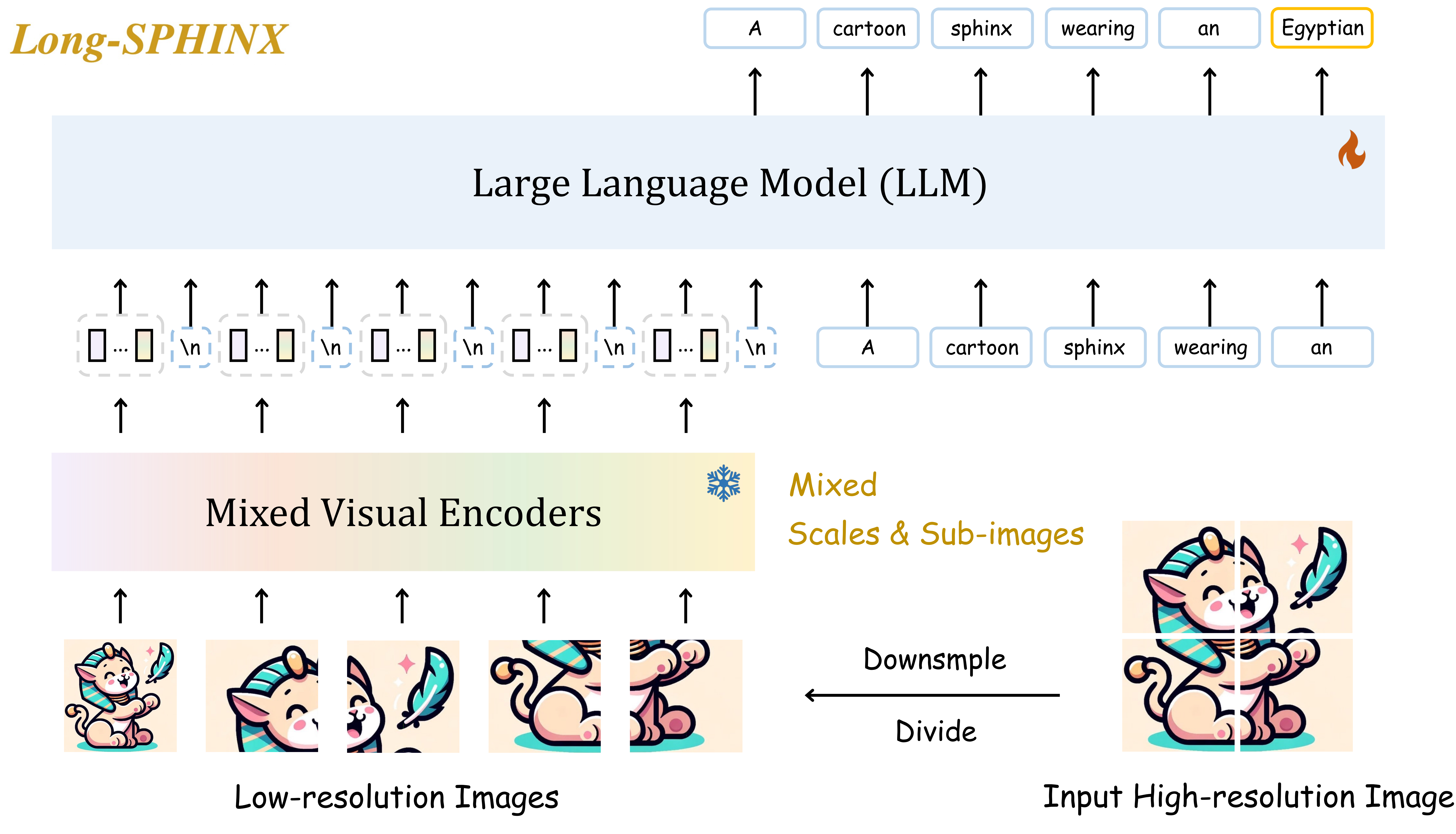

- On top of SPHINX, they propose to further mix visual scales and sub-images for better capture fine-grained semantics on high-resolution images, producing “LongSPHINX”.

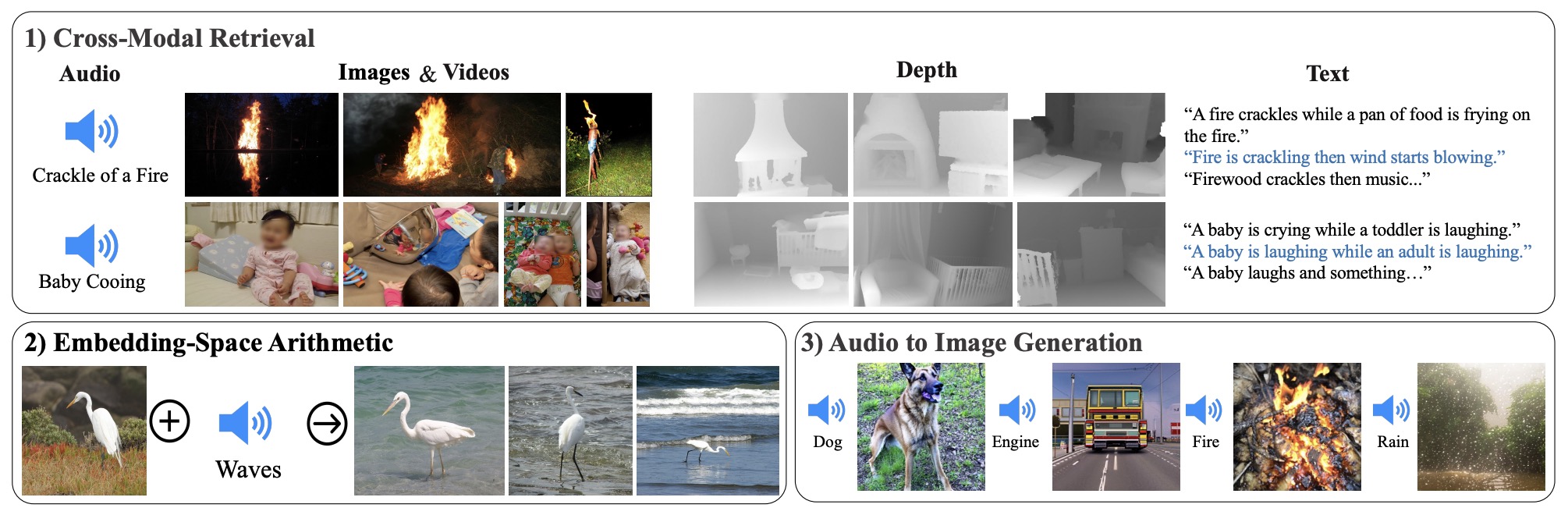

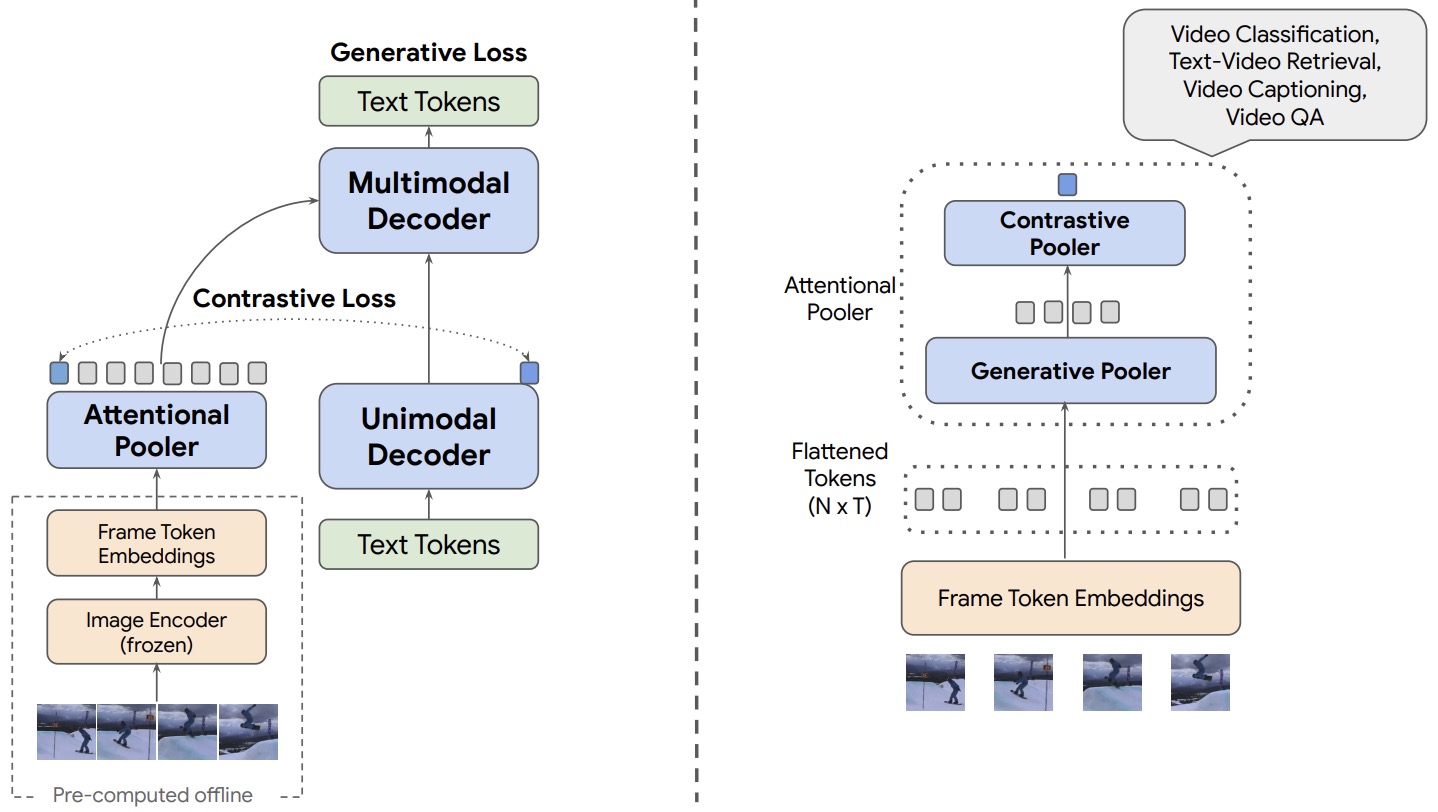

MIRASOL3B

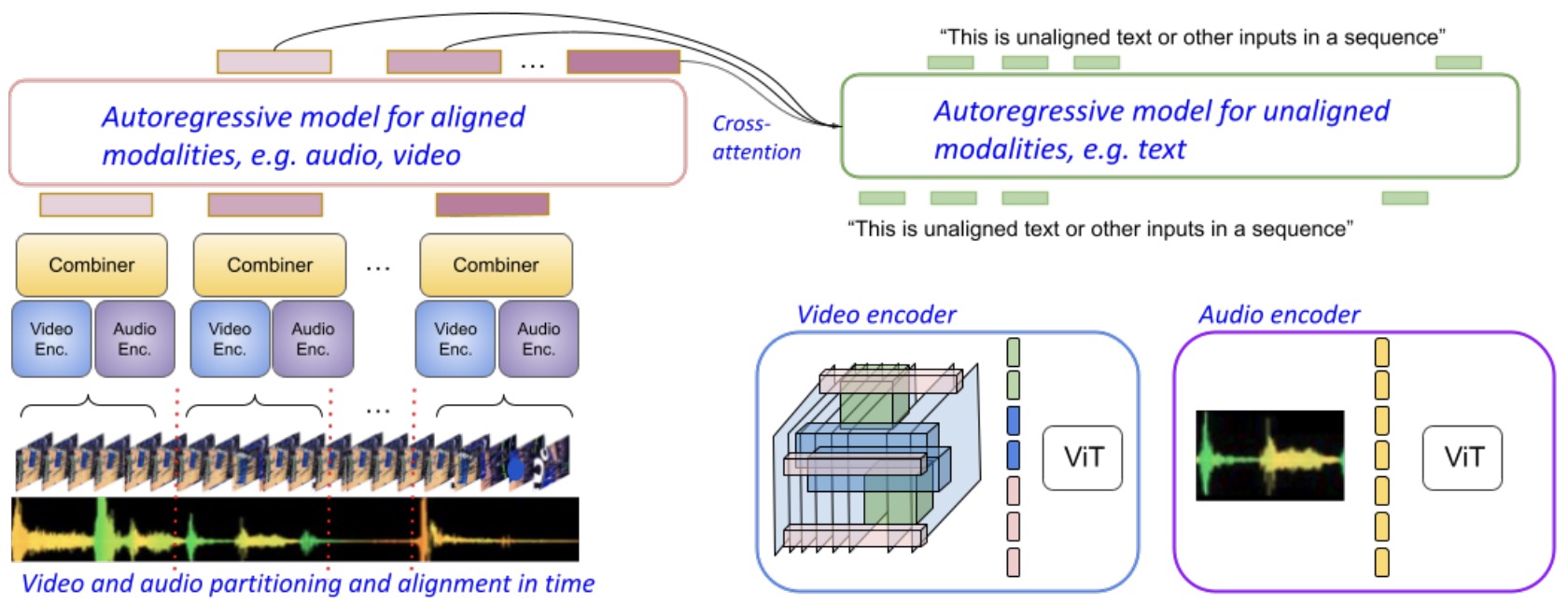

- Proposed in MIRASOL3B: A Multimodal Autoregressive Model for Time-Aligned and Contextual Modalities by Piergiovanni et al. from Google DeepMind and Google Research, MIRASOL3B is a multimodal autoregressive model adept at processing time-aligned modalities (audio and video) and non-time-aligned modality (text), to produce textual outputs.

- The model’s architecture uniquely handles the processing of audio and video. It starts by dividing long video-audio sequences, such as a 10-minute clip, into smaller, manageable chunks (e.g., 1-minute each). Each video chunk, containing \(V\) frames, is passed through a video encoder/temporal image encoder, while the corresponding audio chunk goes through an audio encoder.

- These processed chunks generate \(V\) video tokens and \(A\) audio tokens per chunk. These tokens are then sent to a Transformer block (\(T_VA\)), termed the Combiner. The Combiner effectively fuses video and audio features into a compressed representation of \(M\) tokens, each represented as a tensor of shape \((m, d)\), where \(d\) denotes the embedding size.

- MIRASOL3B’s autoregressive training involves predicting the next set of features \(X_t\) based on the preceding features \(X_0\) to \(X_{(t-1)}\), similar to how GPT predicts the next word in a sequence.

- For textual integration, prompts or questions are fed to a separate Transformer block that employs cross-attention on the hidden features produced by the Combiner. This cross-modal interaction allows the text to leverage audio-video features for richer contextual understanding.

- The following figure from the paper illustrates the Mirasol3B model architecture consists of an autoregressive model for the time-aligned modalities, such as audio and video, which are partitioned in chunks (left) and an autoregressive model for the unaligned context modalities, which are still sequential, e.g., text (right). This allows adequate computational capacity to the video/audio time-synchronized inputs, including processing them in time autoregressively, before fusing with the autoregressive decoder for unaligned text (right). Joint feature learning is conducted by the Combiner, balancing the need for compact representations and allowing sufficiently informative features to be processed in time.

- With just 3 billion parameters, MIRASOL3B demonstrates state-of-the-art performance across various benchmarks. It excels in handling long-duration media inputs and shows versatility in integrating different modalities.

- The model was pretrained on the Video-Text Pairs (VTP) dataset using around 12% of the data. During pretraining, all losses were weighted equally, with the unaligned text loss increasing tenfold in the fine-tuning phase.

- Comprehensive ablation studies in the paper highlight the effects of different model components and configurations, emphasizing the model’s ability to maintain content consistency and capture dynamic changes in long video-audio sequences.

BLIP

- Proposed in BLIP: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training for Unified Vision-Language Understanding and Generation by Li et al. from Salesforce Research.

- They present a novel Vision-Language Pre-training (VLP) framework named BLIP. Unlike most existing pre-trained models, BLIP excels in both understanding-based and generation-based tasks. It addresses the limitations of relying on noisy web-based image-text pairs for training, demonstrating significant improvements in various vision-language tasks.

- Technical and Implementation Details: BLIP consists of two primary innovations:

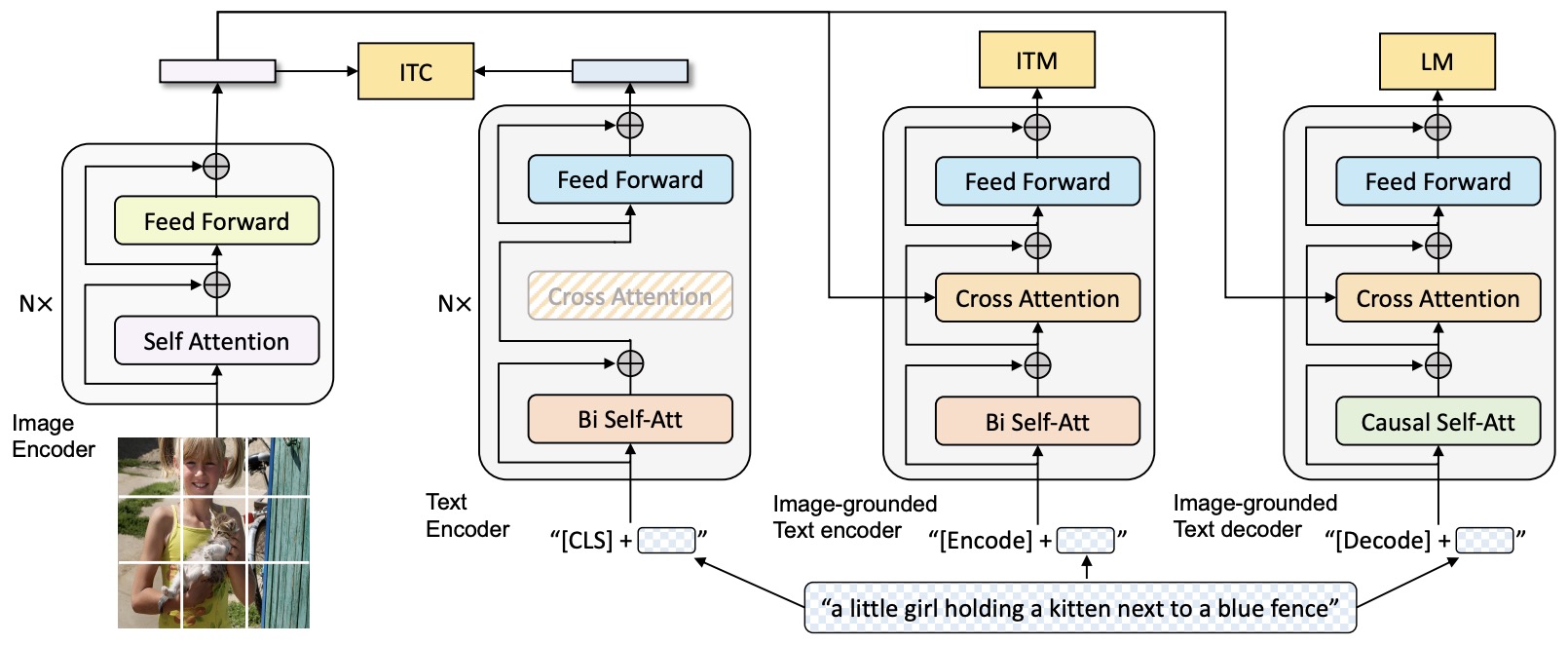

- Multimodal Mixture of Encoder-Decoder (MED): This new architecture effectively multitasks in pre-training and allows flexible transfer learning. It operates in three modes: as a unimodal encoder, an image-grounded text encoder, or an image-grounded text decoder. MED employs a visual transformer as an image encoder, dividing an input image into patches encoded into a sequence of embeddings. The text encoder and decoder share all parameters except for the self-attention layers to enhance efficiency. The model is pre-trained with three objectives: image-text contrastive learning (ITC), image-text matching (ITM), and image-conditioned language modeling (LM).

- Image-Text Contrastive Loss (ITC): This loss function focuses on aligning the feature spaces of visual and textual representations. The goal is to bring closer the embeddings of positive image-text pairs while distancing the embeddings of negative pairs. This objective is crucial for improving vision and language understanding. The equation is: \(ITC = -\log \frac{\exp(sim(v_i, t_i)/\tau)}{\sum_{j=1}^N \exp(sim(v_i, t_j)/\tau)}\) where \(v_i\) and \(t_i\) are the image and text embeddings of the \(i^{th}\) positive pair, \(sim\) is a similarity function, \(\tau\) is a temperature scaling parameter, and \(N\) is the number of negative samples.

- Image-Text Matching Loss (ITM): This objective is a more complex and nuanced task compared to ITC. It aims to learn a fine-grained, multimodal representation of image-text pairs, focusing on the alignment between visual and linguistic elements. ITM functions as a binary classification task, where the model predicts whether an image-text pair is correctly matched. This involves using an image-grounded text encoder that takes the multimodal representation and predicts the match/non-match status. The ITM loss is especially significant in training the model to understand the subtleties and nuances of how text and images relate, going beyond mere surface-level associations. To ensure informative training, a hard negative mining strategy is employed, selecting more challenging negative pairs based on their contrastive similarity, thereby enhancing the model’s discriminative ability. The loss function can be expressed as: \(ITM = -y \log(\sigma(f(v, t))) - (1 - y) \log(1 - \sigma(f(v, t)))\) where \(v\) and \(t\) are the visual and textual embeddings, \(y\) is the label indicating if the pair is a match (1) or not (0), \(\sigma\) denotes the sigmoid function, and \(f(v, t)\) represents the function that combines the embeddings to produce a match score.

- Language Modeling Loss (LM): This loss optimizes the generation of textual descriptions from images, used in the image-grounded text decoder. It aims to generate textual descriptions given an image, training the model to maximize the likelihood of the text in an autoregressive manner. It is typically formulated as a cross-entropy loss over the sequence of words in the text: \(LM = -\sum_{t=1}^{T} \log P(w_t | w_{\<t}, I)\) where \(w_t\) is the \(t^{th}\) word in the caption, \(w_{\<t}\) represents the sequence of words before \(w_t\), and \(I\) is the input image.

- Captioning and Filtering (CapFilt): This method improves the quality of training data from noisy web-based image-text pairs. It involves a captioner module, which generates synthetic captions for web images, and a filter module, which removes noisy captions from both web texts and synthetic texts. Both modules are derived from the pre-trained MED model and fine-tuned on the COCO dataset. CapFilt allows the model to learn from a refined dataset, leading to performance improvements in downstream tasks.

- Multimodal Mixture of Encoder-Decoder (MED): This new architecture effectively multitasks in pre-training and allows flexible transfer learning. It operates in three modes: as a unimodal encoder, an image-grounded text encoder, or an image-grounded text decoder. MED employs a visual transformer as an image encoder, dividing an input image into patches encoded into a sequence of embeddings. The text encoder and decoder share all parameters except for the self-attention layers to enhance efficiency. The model is pre-trained with three objectives: image-text contrastive learning (ITC), image-text matching (ITM), and image-conditioned language modeling (LM).

- The figure below from the paper shows the pre-training model architecture and objectives of BLIP (same parameters have the same color). We propose multimodal mixture of encoder-decoder, a unified vision-language model which can operate in one of the three functionalities: (1) Unimodal encoder is trained with an image-text contrastive (ITC) loss to align the vision and language representations. (2) Image-grounded text encoder uses additional cross-attention layers to model vision-language interactions, and is trained with a image-text matching (ITM) loss to distinguish between positive and negative image-text pairs. (3) Image-grounded text decoder replaces the bi-directional self-attention layers with causal self-attention layers, and shares the same cross-attention layers and feed forward networks as the encoder. The decoder is trained with a language modeling (LM) loss to generate captions given images.

- Experimentation and Results:

- BLIP’s models were implemented in PyTorch and pre-trained on a dataset including 14 million images, comprising both human-annotated and web-collected image-text pairs.

- The experiments showed that the captioner and filter, when used in conjunction, significantly improved performance in downstream tasks like image-text retrieval and image captioning.

- The CapFilt approach proved to be scalable with larger datasets and models, further boosting performance.

- The diversity introduced by nucleus sampling in generating synthetic captions was found to be key in achieving better results, outperforming deterministic methods like beam search.

- Parameter sharing strategies during pre-training were explored, with results indicating that sharing all layers except for self-attention layers provided the best performance.

- BLIP achieved substantial improvements over existing methods in image-text retrieval and image captioning tasks, outperforming the previous best models on standard datasets like COCO and Flickr30K.

- Conclusion:

- BLIP represents a significant advancement in unified vision-language understanding and generation tasks, effectively utilizing noisy web data and achieving state-of-the-art results in various benchmarks. The framework’s ability to adapt to both understanding and generation tasks, along with its robustness in handling web-collected noisy data, marks it as a notable contribution to the field of Vision-Language Pre-training.

- Code

BLIP-2

- Proposed in BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models by Li et al. from Salesforce Research.

- BLIP-2 utilizes a cost-effective pre-training strategy for vision-language models using off-the-shelf frozen image encoders and large language models (LLMs). The core component, the Querying Transformer (Q-Former), originally from the BLIP model, bridges the modality gap in a two-stage bootstrapping process, leading to state-of-the-art performance in vision-language tasks with significantly fewer trainable parameters. BLIP-2 leverages existing unimodal models from vision and language domains, utilizing Q-Former ti specifically address the challenge of interoperability between different modality embeddings, such as aligning visual and textual representations.

- Q-Former Architecture and Functionality””

- Q-Former Design: The Q-Former, central to BLIP-2, is a trainable BERT encoder with a causal language modeling head, akin to GPT. It integrates one cross-attention layer for every two layers of BERT and introduces a fixed number of 32 trainable query vectors, crucial for modality alignment.

- Embedding Alignment: The query vectors are designed to extract the most useful features from one of the frozen encoders, aligning embeddings across modalities, such as visual and textual spaces.

- Modality Handling: In BLIP-2, which is a vision-language model, the Q-Former uses cross-attention between query vectors and image patch embeddings to obtain image embeddings. For a hypothetical model with purely textual input, it functions like a normal BERT Model, bypassing cross-attention or query vectors.

- Methodology: BLIP-2 employs a two-stage bootstrapping method with the Q-Former:

- Vision-Language Representation Learning: Utilizes a frozen image encoder for vision-language representation learning. The Q-Former is trained to extract visual features most relevant to text, employing three pre-training objectives with different attention masking strategies: Image-Text Contrastive Learning (ITC), Image-grounded Text Generation (ITG), and Image-Text Matching (ITM).

- Vision-to-Language Generative Learning: Connects the Q-Former to a frozen LLM. The model uses a fully-connected layer to adapt the output query embeddings from the Q-Former to the LLM’s input dimension, functioning as soft visual prompts. This stage is compatible with both decoder-based and encoder-decoder-based LLMs.

- The following figure from the paper shows an overview of BLIP-2’s framework. They pre-train a lightweight Querying Transformer following a two-stage strategy to bridge the modality gap. The first stage bootstraps vision-language representation learning from a frozen image encoder. The second stage bootstraps vision-to-language generative learning from a frozen LLM, which enables zero-shot instructed image-to-text generation.

- The following figure from the paper shows: (Left) Model architecture of Q-Former and BLIP-2’s first-stage vision-language representation learning objectives. They jointly optimize three objectives which enforce the queries (a set of learnable embeddings) to extract visual representation most relevant to the text. (Right) The self-attention masking strategy for each objective to control query-text interaction.

- The following figure from the paper shows BLIP-2’s second-stage vision-to-language generative pre-training, which bootstraps from frozen large language models (LLMs). (Top) Bootstrapping a decoder-based LLM (e.g. OPT). (Bottom) Bootstrapping an encoder-decoder-based LLM (e.g. FlanT5). The fully-connected layer adapts from the output dimension of the Q-Former to the input dimension of the chosen LLM.

- Training: The Q-Former in BLIP-2 is trained on multiple tasks, including image captioning, image and text embedding alignment via contrastive learning, and classifying image-text pair matches, utilizing special attention masking schemes.

- Implementation Details:

- Pre-training Data: BLIP-2 is trained on a dataset comprising 129 million images from sources like COCO, Visual Genome, CC3M, CC12M, SBU, and LAION400M. Synthetic captions are generated using the CapFilt method and ranked based on image-text similarity.

- Image Encoder and LLMs: The method explores state-of-the-art vision transformer models like ViT-L/14 and ViT-g/14 for the image encoder, and OPT and FlanT5 models for the language model.

- Training Parameters: The model is pre-trained for 250k steps in the first stage and 80k steps in the second stage, using batch sizes tailored for each stage and model. Training utilizes AdamW optimizer, cosine learning rate decay, and images augmented with random resizing and horizontal flipping.

- Capabilities and Limitations: BLIP-2 enables effective zero-shot image-to-text generation, preserving the LLM’s ability to follow text prompts. It shows state-of-the-art results on the zero-shot visual question answering task on datasets like VQAv2 and GQA. However, the model’s performance does not improve with in-context learning using few-shot examples, attributed to the pre-training dataset’s structure. Additionally, BLIP-2 may inherit the risks of LLMs, such as outputting offensive language or propagating bias

- Applications: The Q-Former’s ability to align modalities makes it versatile for various models, including MiniGPT-4 and InstructBlip (Image + Text), and Video-LLaMA (image, video, audio, text). Its capability to produce a fixed sequence of high-information embeddings proves useful in different multimodal contexts.

- Code

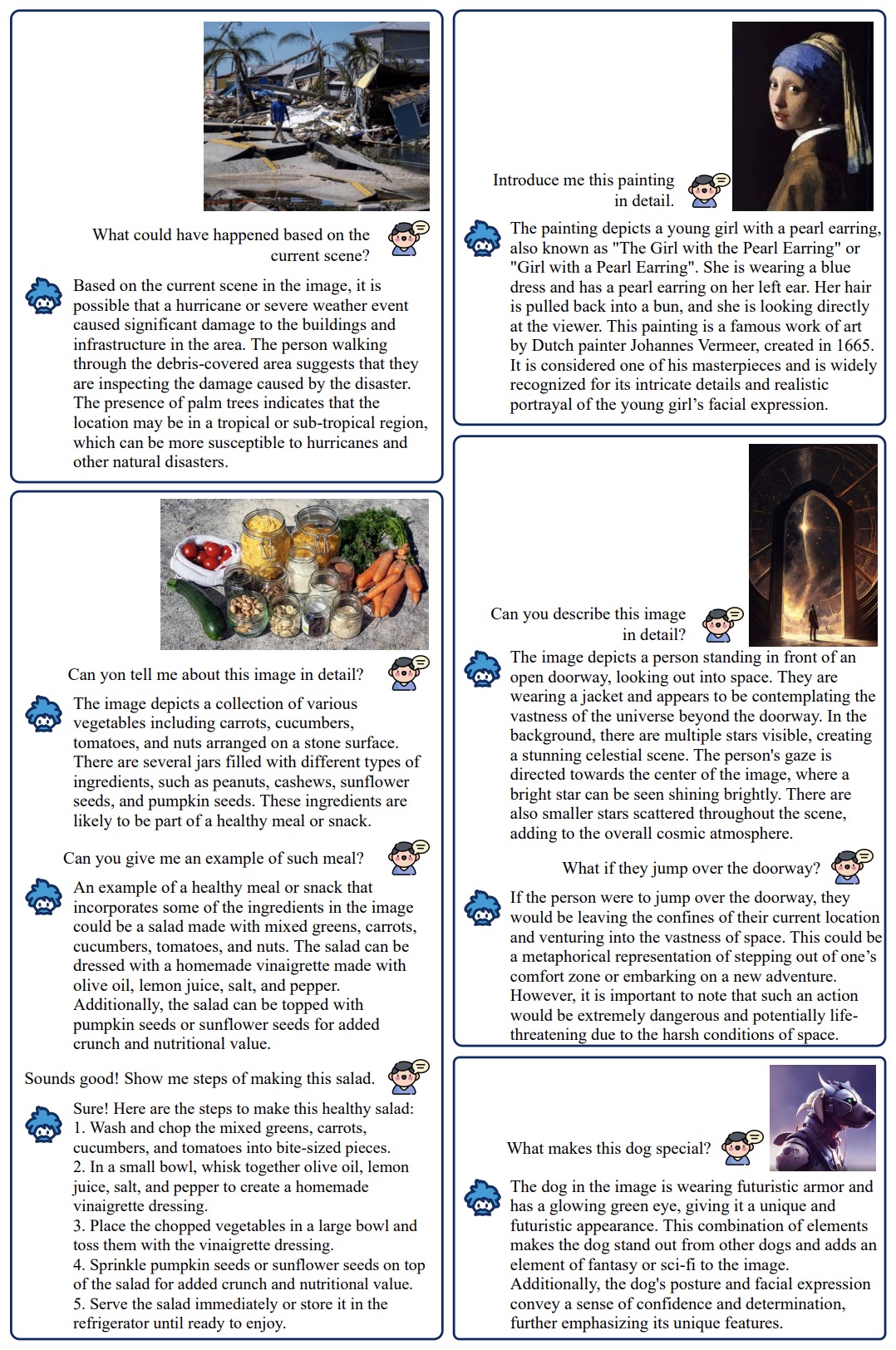

InstructBLIP

- General-purpose language models that can solve various language-domain tasks have emerged driven by the pre-training and instruction-tuning pipeline. However, building general-purpose vision-language models is challenging due to the increased task discrepancy introduced by the additional visual input. Although vision-language pre-training has been widely studied, vision-language instruction tuning remains relatively less explored.

- InstructBLIP was proposed in InstructBLIP: Towards General-purpose Vision-Language Models with Instruction Tuning by Dai et al. from Salesforce Research, HKUST, and NTU Singapore in 2023.

- The paper conducts a systematic and comprehensive study on vision-language instruction tuning based on the pre-trained BLIP-2 models. They gather a wide variety of 26 publicly available datasets, transform them into instruction tuning format and categorize them into two clusters for held-in instruction tuning and held-out zero-shot evaluation. Additionally, they introduce instruction-aware visual feature extraction, a crucial method that enables the model to extract informative features tailored to the given instruction.

- The following figure from the paper shows the model architecture of InstructBLIP. The Q-Former extracts instruction-aware visual features from the output embeddings of the frozen image encoder, and feeds the visual features as soft prompt input to the frozen LLM. We instruction-tune the model with the language modeling loss to generate the response.

- The resulting InstructBLIP models achieve state-of-the-art zero-shot performance across all 13 held-out datasets, substantially outperforming BLIP-2 and the larger Flamingo.

- Their models also lead to state-of-the-art performance when finetuned on individual downstream tasks (e.g., 90.7% accuracy on ScienceQA IMG). Furthermore, they qualitatively demonstrate the advantages of InstructBLIP over concurrent multimodal models.

- The figure below from the paper shows a few qualitative examples generated by our InstructBLIP Vicuna model. Here, a range of its diverse capabilities are demonstrated, including complex visual scene understanding and reasoning, knowledge-grounded image description, multi-turn visual conversation, etc.

- Code.

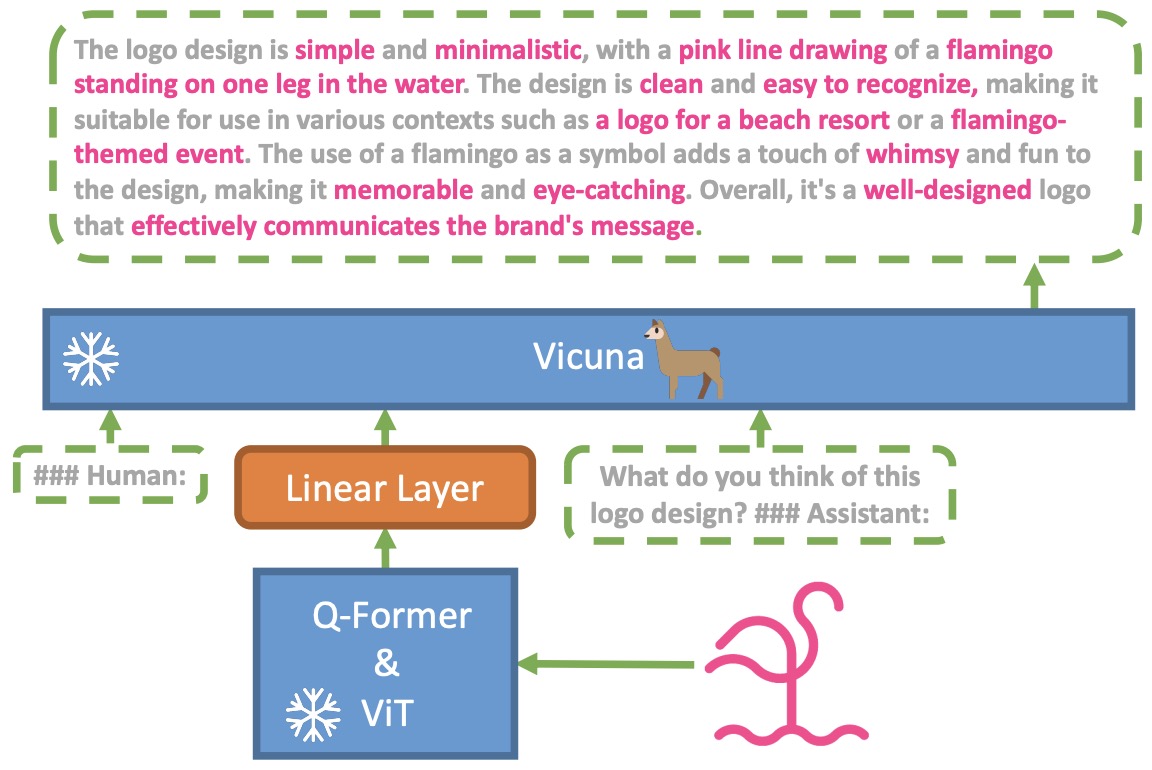

MiniGPT-4

- Proposed in MiniGPT-4: Enhancing Vision-Language Understanding with Advanced Large Language Models by Zhu et al. from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

- The paper explores whether aligning visual features with advanced large language models (LLMs) like Vicuna can replicate the impressive vision-language capabilities exhibited by GPT-4.

- The authors present MiniGPT-4 which combines a frozen visual encoder (ViT + Q-Former from BLIP-2) with a frozen Vicuna LLM using just a single trainable projection layer.

- The model undergoes a two-stage training process. The first stage involves pretraining on a large collection of aligned image-text pairs. The second stage involves finetuning with a smaller, detailed image description dataset to enhance generation reliability and usability. MiniGPT-4 was initially pretrained on 5M image-caption pairs, then finetuned on 3.5K detailed image descriptions to improve language quality.

- Without training the vision or language modules, MiniGPT-4 demonstrates abilities similar to GPT-4, such as generating intricate image descriptions, creating websites from handwritten text, and explaining unusual visual phenomena. Additionally, it showcases unique capabilities like generating detailed cooking recipes from food photos, writing stories or poems inspired by images, and diagnosing problems in photos with solutions. Quantitative analysis showed strong performance in tasks like meme interpretation, recipe generation, advertisement creation, and poem composition compared to BLIP-2.

- The finetuning process in the second stage significantly improved the naturalness and reliability of language outputs. This process was efficient, requiring only 400 training steps with a batch size of 12, and took around 7 minutes with a single A100 GPU.

- Additional emergent skills are observed like composing ads/poems from images, generating cooking recipes from food photos, retrieving facts from movie images etc. Aligning visual features with advanced LLMs appears critical for GPT-4-like capabilities, as evidenced by the absence of such skills in models like BLIP-2 with less powerful language models.

- The figure below from the paper shows the architecture of MiniGPT-4. It consists of a vision encoder with a pretrained ViT and Q-Former, a single linear projection layer, and an advanced Vicuna large language model. MiniGPT-4 only requires training the linear projection layer to align the visual features with the Vicuna.

- The simple methodology verifies that advanced vision-language abilities can emerge from properly aligning visual encoders with large language models, without necessarily needing huge datasets or model capacity.

- Despite its advancements, MiniGPT-4 faces limitations like hallucination of nonexistent knowledge and struggles with spatial localization. Future research could explore training on datasets designed for spatial information understanding to mitigate these issues.

- Project page; Code; HuggignFace Space; Video; Dataset.

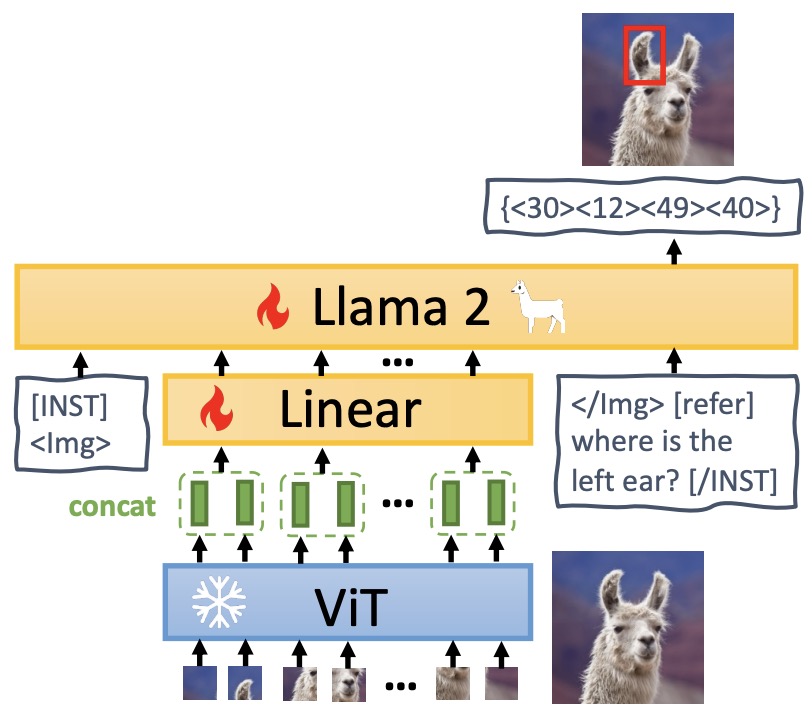

MiniGPT-v2

- Proposed in MiniGPT-v2: Large Language Model as a Unified Interface for Vision-Language Multi-task Learning by Chen et al. from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology and Meta AI Research.

- MiniGPT-v2 is a model designed to handle various vision-language tasks such as image description, visual question answering, and visual grounding.

- MiniGPT-v2 uniquely incorporates task-specific identifiers in training, allowing it to distinguish and effectively handle different task instructions. This is achieved by using a three-stage training strategy with a mix of weakly-labeled image-text datasets and multi-modal instructional datasets. The model architecture includes a visual backbone (adapted from EVA), a linear projection layer, and a large language model (LLaMA2-chat, 7B), trained with high-resolution images to process visual tokens efficiently.

- The figure below from the paper shows the architecture of MiniGPT-v2. The model takes a ViT visual backbone, which remains frozen during all training phases. We concatenate four adjacent visual output tokens from ViT backbone and project them into LLaMA-2 language model space via a linear projection layer.

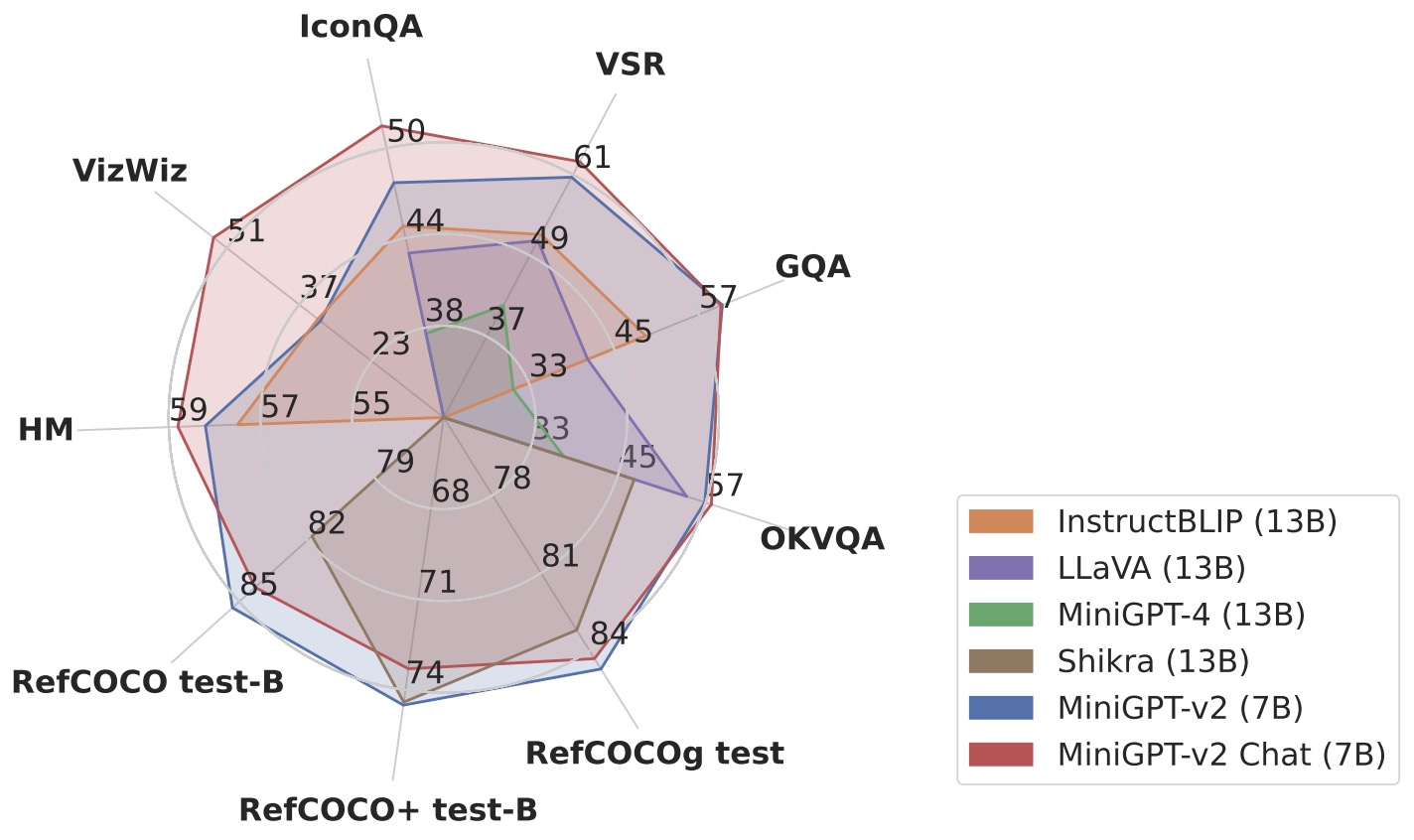

- In terms of performance, MiniGPT-v2 demonstrates superior results in various visual question-answering and visual grounding benchmarks, outperforming other generalist models like MiniGPT-4, InstructBLIP, LLaVA, and Shikra. It also shows a robust ability against hallucinations in image description tasks.

- The figure below from the paper shows that MiniGPT-v2 achieves state-of-the-art performances on a broad range of vision-language tasks compared with other generalist models.

- The paper highlights the importance of task identifier tokens, which significantly enhance the model’s efficiency in multi-task learning. These tokens have been shown to be crucial in the model’s strong performance across multiple tasks.

- Despite its capabilities, MiniGPT-v2 faces challenges like occasional hallucinations and the need for more high-quality image-text aligned data for improvement.

- The paper concludes that MiniGPT-v2, with its novel approach of task-specific identifiers and a unified interface, sets a new benchmark in multi-task vision-language learning. Its adaptability to new tasks underscores its potential in vision-language applications.

- Project page; Code; HuggignFace Space; Demo; Video

LLaVA-Plus

- Proposed in LLaVA-Plus: Learning to Use Tools for Creating Multimodal Agents by Liu et al. from Tsinghua University, Microsoft Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and HKUST IDEA Research.

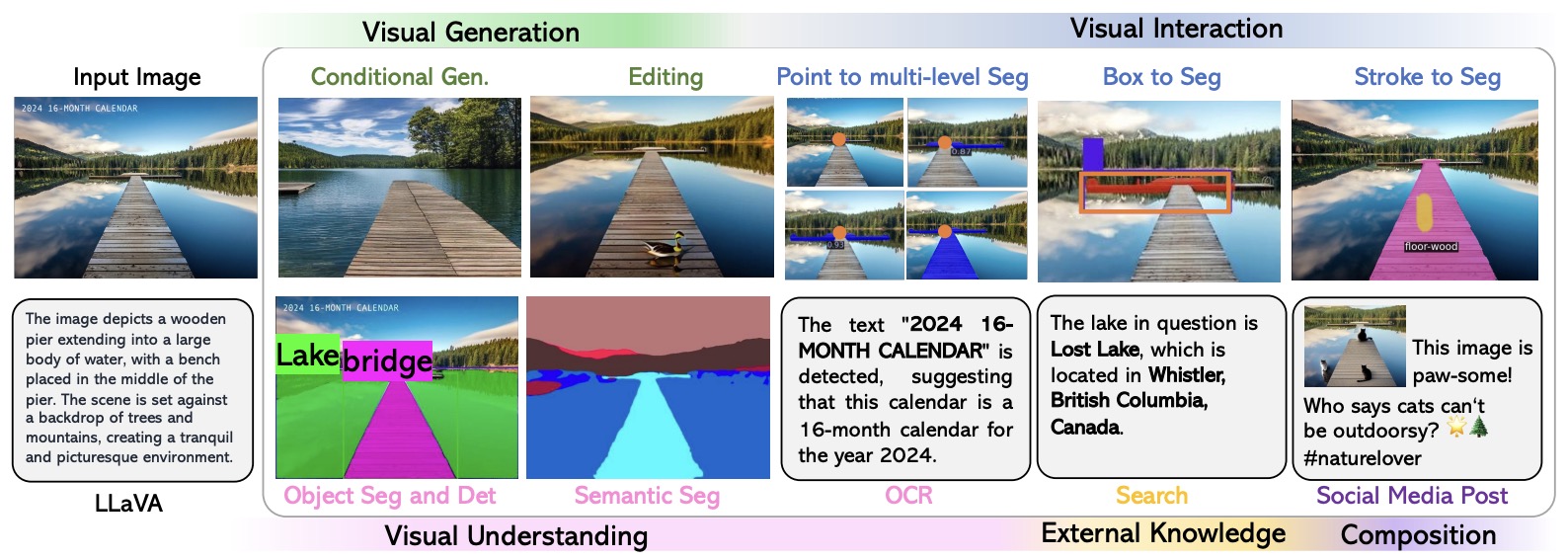

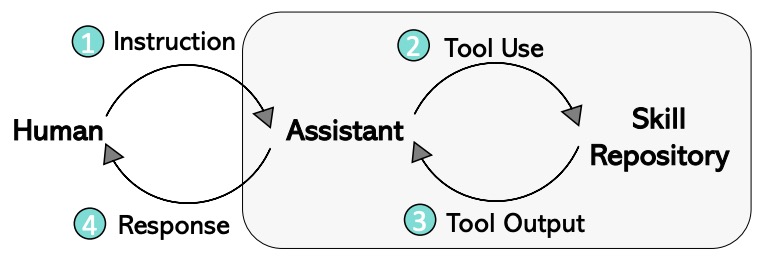

- LLaVA-Plus is a general-purpose multimodal assistant that systematically expands the capabilities of large multimodal models (LMMs) through visual instruction tuning.

- LLaVA-Plus maintains a skill repository with a wide array of vision and vision-language pre-trained models, allowing it to activate relevant tools in response to user inputs and compose execution results for various tasks.

- The figure below from the paper offers a visual illustration of LLaVA-Plus’ capabilities enabled by learning to use skills.

- The model is trained on multimodal instruction-following data, covering examples of tool usage in visual understanding, generation, and external knowledge retrieval, demonstrating significant improvements over its predecessor, LLaVA, in both existing and new capabilities.

- The training approach includes using GPT-4 for generating instruction data and integrating new tools through instruction tuning, allowing continuous enhancement of the model’s abilities.

- The figure below from the paper shows the four-step LLaVA-Plus pipeline.

- Empirical results show that LLaVA-Plus achieves state-of-the-art performance on VisiT-Bench, a benchmark for evaluating multimodal agents in real-life tasks, and is more effective in tool use compared to other tool-augmented LLMs.

- The paper also highlights the model’s ability to adapt to various scenarios, such as external knowledge retrieval, image generation, and interactive segmentation, showcasing its versatility in handling real-world multimodal tasks.

- Project page; Code; Dataset; Demo; Model

BakLLaVA

- BakLLaVA is a VLM developed by LAION, Ontocord, and Skunkworks AI. BakLLaVA uses a Mistral 7B base augmented with the LLaVA 1.5 architecture. Used in combination with llama.cpp, a tool for running the LLaMA model in C++, you can use BakLLaVA on a laptop, provided you have enough GPU resources available.

- BakLLaVA is a faster and less resource-intensive alternative to GPT-4 with Vision.

LLaVA-1.5

- LLaVA-1.5 offers support for LLaMA-2, LoRA training with consumer GPUs, higher resolution (336x336), 4-/8- inference, etc.

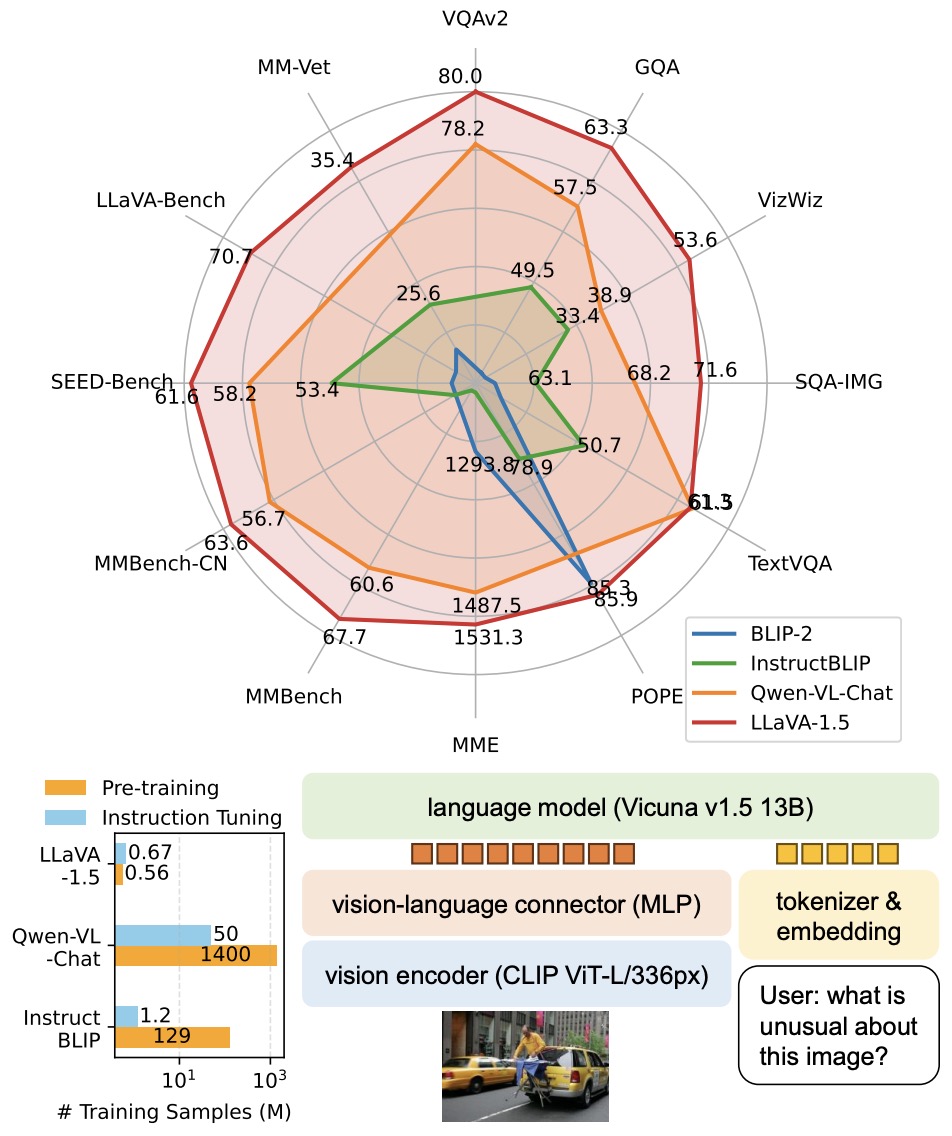

- Introduced in Improved Baselines with Visual Instruction Tuning by Liu et al. from UW–Madison and MSR, LLaVA-1.5 focuses on enhancing multimodal models through visual instruction tuning.

- The paper presents improvements to the Large Multimodal Model (LMM) known as LLaVA, emphasizing its power and data efficiency. Simple modifications are proposed, including using CLIP-ViT-L-336px with an MLP projection and adding academic-task-oriented VQA data with simple response formatting prompts.

- A major achievement is establishing stronger baselines for LLaVA, which now achieves state-of-the-art performance across 11 benchmarks using only 1.2 million publicly available data points and completing training in about 1 day on a single 8-A100 node.

- The authors highlight two key improvements: an MLP cross-modal connector and incorporating academic task-related data like VQA. These are shown to be orthogonal to LLaVA’s framework and significantly enhance its multimodal understanding capabilities. LLaVA-1.5, the enhanced version, significantly outperforms the original LLaVA in a wide range of benchmarks, using a significantly smaller dataset for pretraining and instruction tuning compared to other methods.

- The figure below from the paper illustrates that LLaVA-1.5 achieves SoTA on a broad range of 11 tasks (Top), with high training sample efficiency (Left) and simple modifications to LLaVA (Right): an MLP connector and including academic-task-oriented data with response formatting prompts.

- The paper discusses limitations, including the use of full image patches in LLaVA, which may prolong training iterations. Despite its improved capability in following complex instructions, LLaVA-1.5 still has limitations in processing multiple images and certain domain-specific problem-solving tasks.

- Overall, the work demonstrates significant advancements in visual instruction tuning for multimodal models, making state-of-the-art research more accessible and providing a reference for future work in this field.

- Code.

CogVLM

- This paper by Wang et al. from Zhipu AI and Tsinghua University introduces CogVLM, an open-source visual language foundation model. CogVLM offers an answer to the question: is it possible to retain the NLP capabilities of the large language model while adding top-notch visual understanding abilities? CogVLM is distinctive for integrating a trainable visual expert module with a pretrained language model, enabling deep fusion of visual and language features.

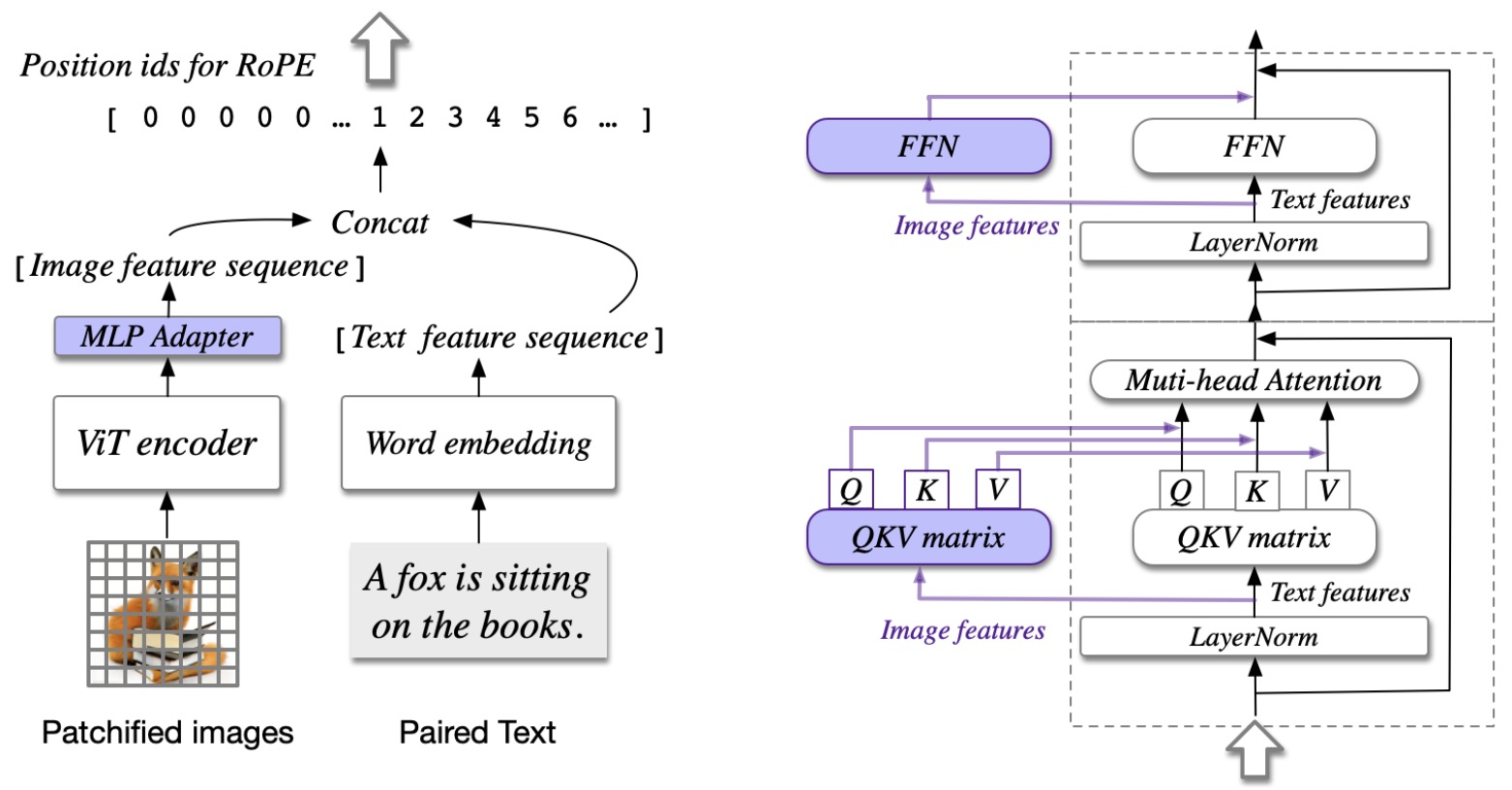

- The architecture of CogVLM comprises four main components: a vision transformer (ViT) encoder, an MLP adapter, a pretrained large language model (GPT-style), and a visual expert module. The ViT encoder, such as EVA2-CLIP-E, processes images, while the MLP adapter maps the output of ViT into the same space as the text features.

- The visual expert module, added to each layer of the model, consists of a QKV matrix and an MLP, both mirroring the structure in the pretrained language model. This setup allows for more effective integration of image and text data, enhancing the model’s capabilities in handling visual language tasks.

- Since all the parameters in the original language model are fixed, the behaviors are the same as in the original language model if the input sequence contains no image. This inspiration arises from the comparison between P-Tuning and LoRA in efficient finetuning, where p-tuning learns a task prefix embedding in the input while LoRA adapts the model weights in each layer via a low-rank matrix. As a result, LoRA performs better and more stable. A similar phenomenon might also exist in VLM, because in the shallow alignment methods, the image features act like the prefix embedding in P-Tuning.

- The figure below from the paper shows the architecture of CogVLM. (a) The illustration about the input, where an image is processed by a pretrained ViT and mapped into the same space as the text features. (b) The Transformer block in the language model. The image features have a different QKV matrix and FFN. Only the purple parts are trainable.

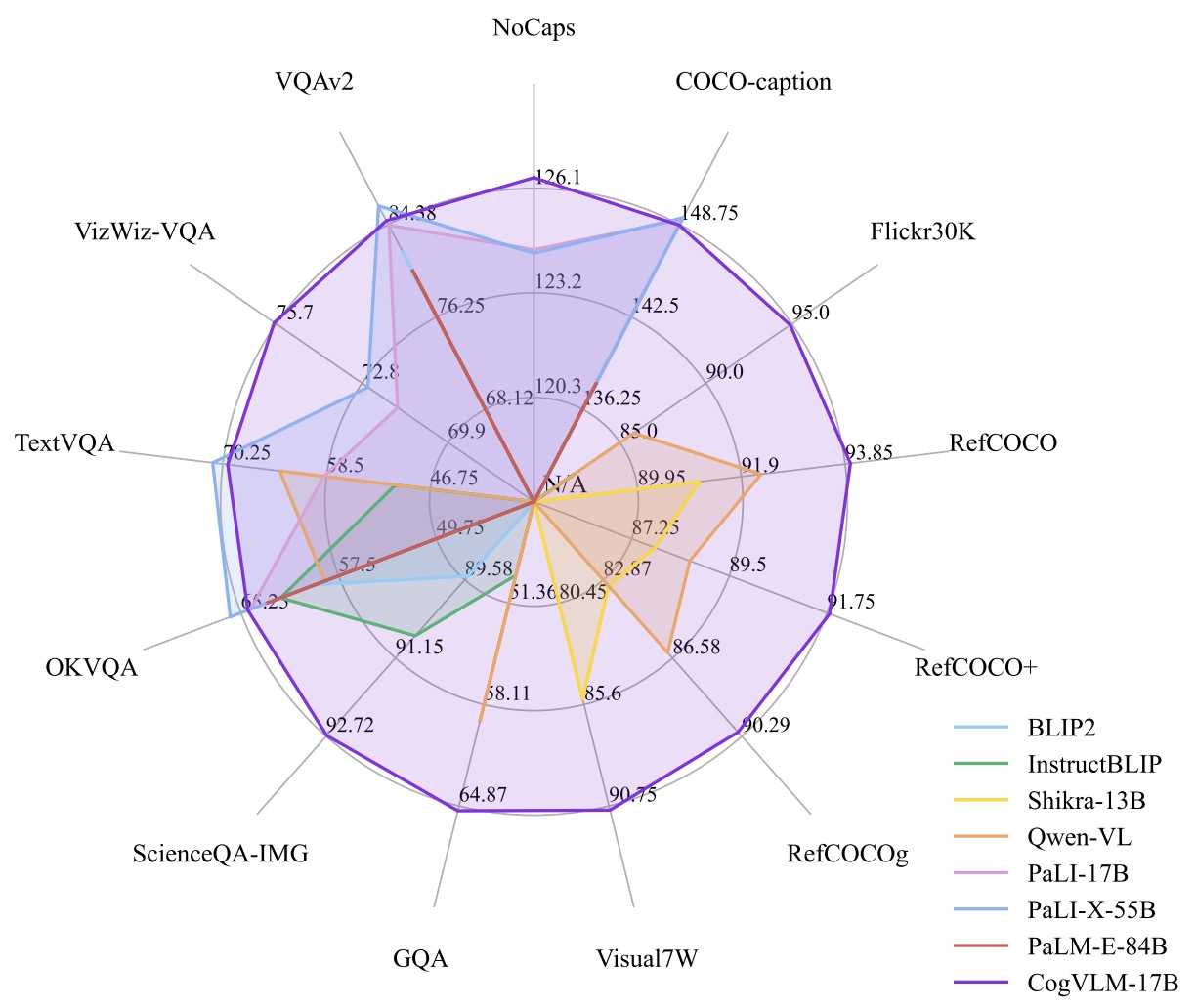

- CogVLM was pretrained on 1.5 billion image-text pairs, using a combination of image captioning loss and Referring Expression Comprehension (REC). It achieved state-of-the-art or second-best performance on 14 classic cross-modal benchmarks, demonstrating its effectiveness.

- The model was further fine-tuned on a range of tasks for alignment with free-form instructions, creating the CogVLM-Chat variant. This version showcased flexibility and adaptability to diverse user instructions, indicating the model’s robustness in real-world applications.

- The paper also includes an ablation study to evaluate the impact of different components and settings on the model’s performance, affirming the significance of the visual expert module and other architectural choices.

- The authors emphasize the model’s deep fusion approach as a major advancement over shallow alignment methods, leading to enhanced performance in multi-modal benchmarks. They anticipate that the open-sourcing of CogVLM will significantly contribute to research and industrial applications in visual understanding.

- The figure below from the paper shows the performance of CogVLM on a broad range of multi-modal tasks compared with existing models.

CogVLM 2

- CogVLM 2 beats GPT4-V, Gemini Pro on TextVQA, DocVQA and ChartQA by a decent margin.

- Specifics:

- 19B parameters

- Llama 3 8B (Instruct) text backbone

- Supports 8K context length

- Upto 1344 X 1344 resolution supported

- Works with both Chinese and English

- Open access with commercial use allowed!

- Hugging Face; Code

FERRET

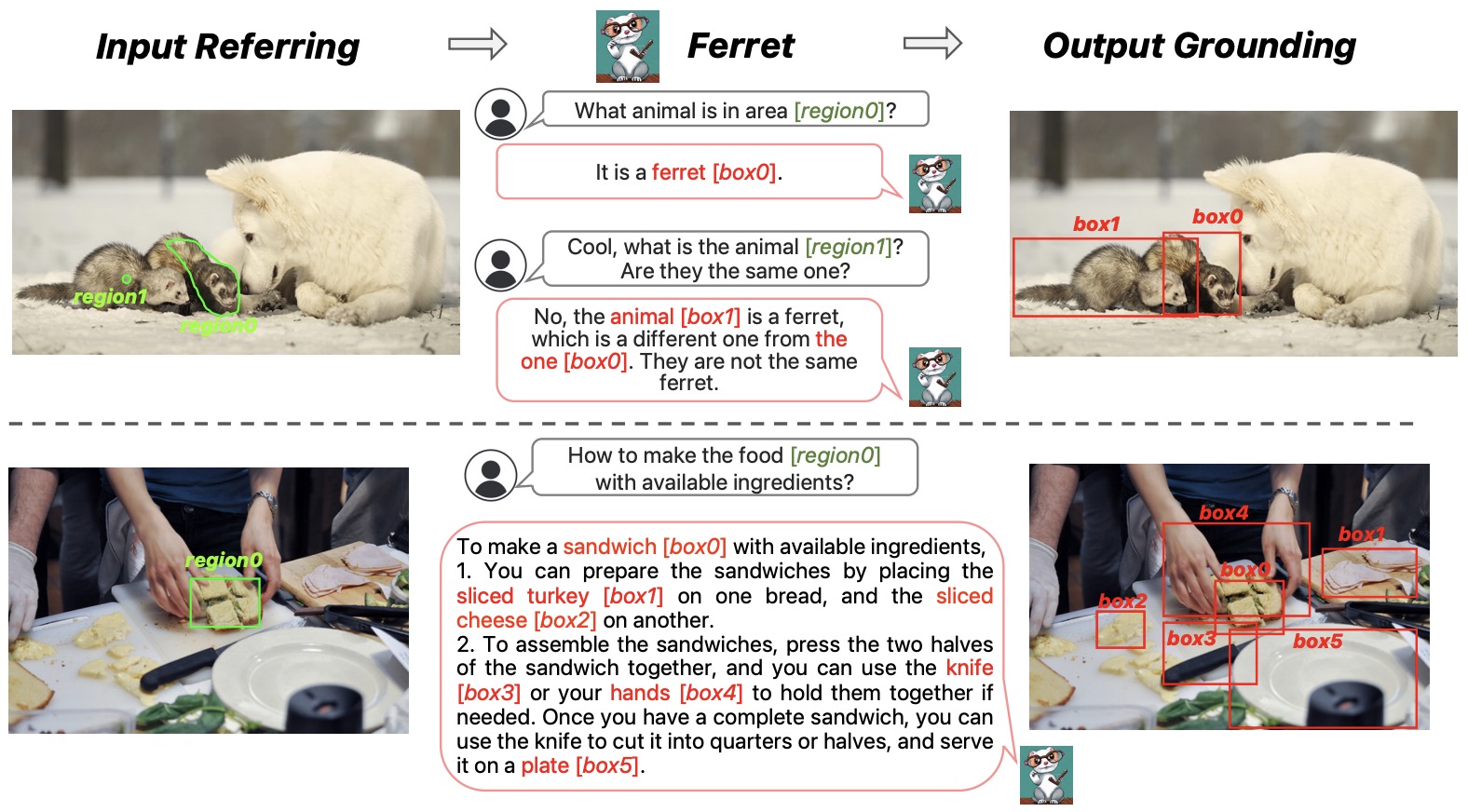

- Proposed in FERRET: Refer and Ground Anything Anywhere at Any Granularity by You et al. from Columbia and Apple, Ferret is a novel Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) capable of spatial referring and grounding in images at various shapes and granularities.

- Ferret stands out in its ability to understand and localize open-vocabulary descriptions within images.

- Key Contributions:

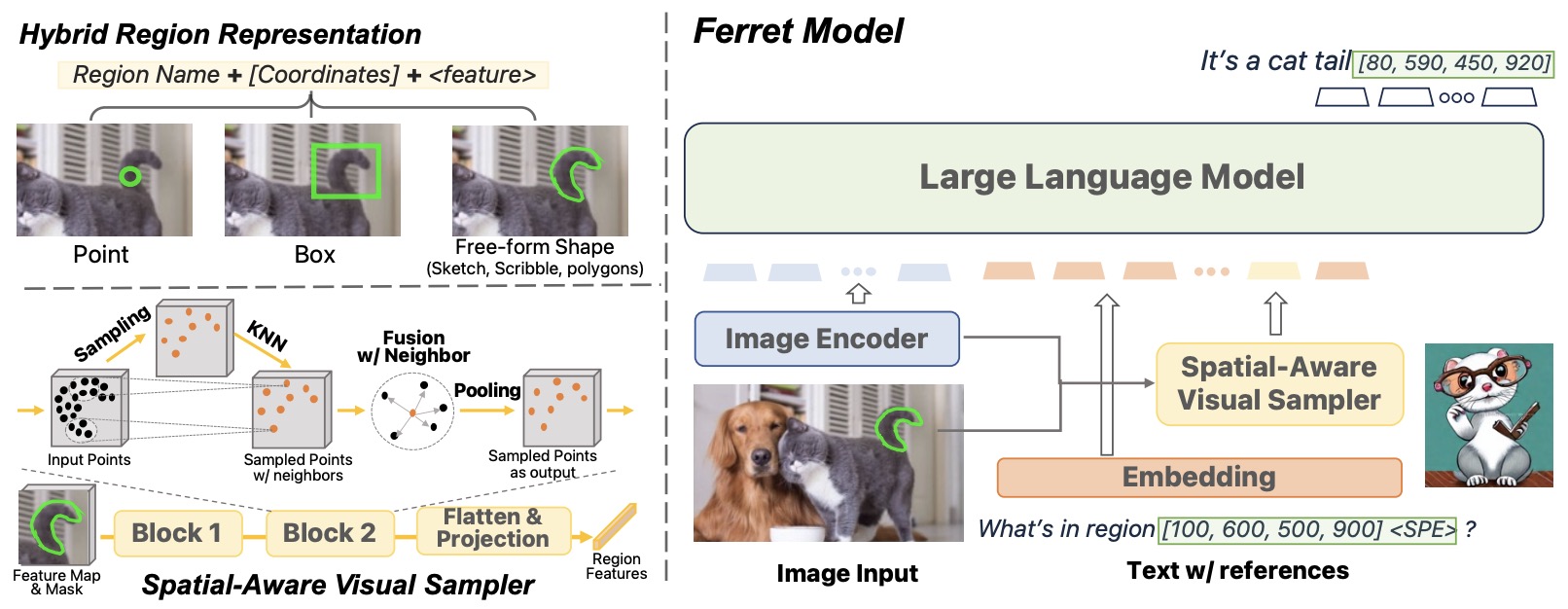

- Hybrid Region Representation: Ferret employs a unique representation combining discrete coordinates and continuous visual features. This approach enables the processing of diverse region inputs like points, bounding boxes, and free-form shapes.

- Spatial-Aware Visual Sampler: To capture continuous features of various region shapes, Ferret uses a specialized sampler adept at handling different sparsity levels in shapes. This allows Ferret to deal with complex and irregular region inputs.

- GRIT Dataset: The Ground-and-Refer Instruction-Tuning (GRIT) dataset was curated for model training. It includes 1.1 million samples covering hierarchical spatial knowledge and contains 95k hard negative samples to enhance robustness.

- Ferret-Bench: A benchmark for evaluating MLLMs on tasks that require both referring and grounding abilities. Ferret excels in these tasks, demonstrating improved spatial understanding and commonsense reasoning capabilities.

- The figure below from the paper shows that Ferret enables referring and grounding capabilities for MLLMs. In terms of referring, a user can refer to a region or an object in point, box, or any free-form shape. The regionN (green) in the input will be replaced by the proposed hybrid representation before being fed into the LLM. In terms of grounding, Ferret is able to accurately ground any open-vocabulary descriptions. The boxN (red) in the output denotes the predicted bounding box coordinates.

- Implementation Details:

- Model Architecture: Ferret’s architecture consists of an image encoder, a spatial-aware visual sampler, and an LLM to model image, text, and region features.

- Input Processing: The model uses a pre-trained visual encoder (CLIP-ViT-L/14) and LLM’s tokenizer for image and text embeddings. Referred regions are denoted using coordinates and a special token for continuous features.

- Output Grounding: Ferret generates box coordinates corresponding to the referred regions/nouns in its output.

- Language Model: Ferret utilizes Vicuna, a decoder-only LLM, instruction-tuned on LLaMA, for language modeling.

- Training: Ferret is trained on the GRIT dataset for three epochs. During training, the model randomly chooses between center points or bounding boxes to represent regions.

- The figure below from the paper shows an overview of the proposed Ferret model architecture. (Left) The proposed hybrid region representation and spatial-aware visual sampler. (Right) Overall model architecture. All parameters besides the image encoder are trainable.

- Evaluations and Findings:

- Performance on Standard Benchmarks: Ferret surpasses existing models in standard referring and grounding tasks.

- Capability in Multimodal Chatting: Ferret significantly improves performance in multimodal chatting tasks, integrating refer-and-ground capabilities.

- Ablation Studies: Studies indicate mutual benefits between grounding and referring data and demonstrate the effectiveness of the spatial-aware visual sampler.

- Reducing Object Hallucination: Notably, Ferret mitigates the issue of object hallucination, a common challenge in multimodal models.

- Ferret represents a significant advancement in MLLMs, offering robust and versatile spatial referring and grounding abilities. Its innovative approach and superior performance in various tasks mark it as a promising tool for practical applications in vision-language learning.

- Code

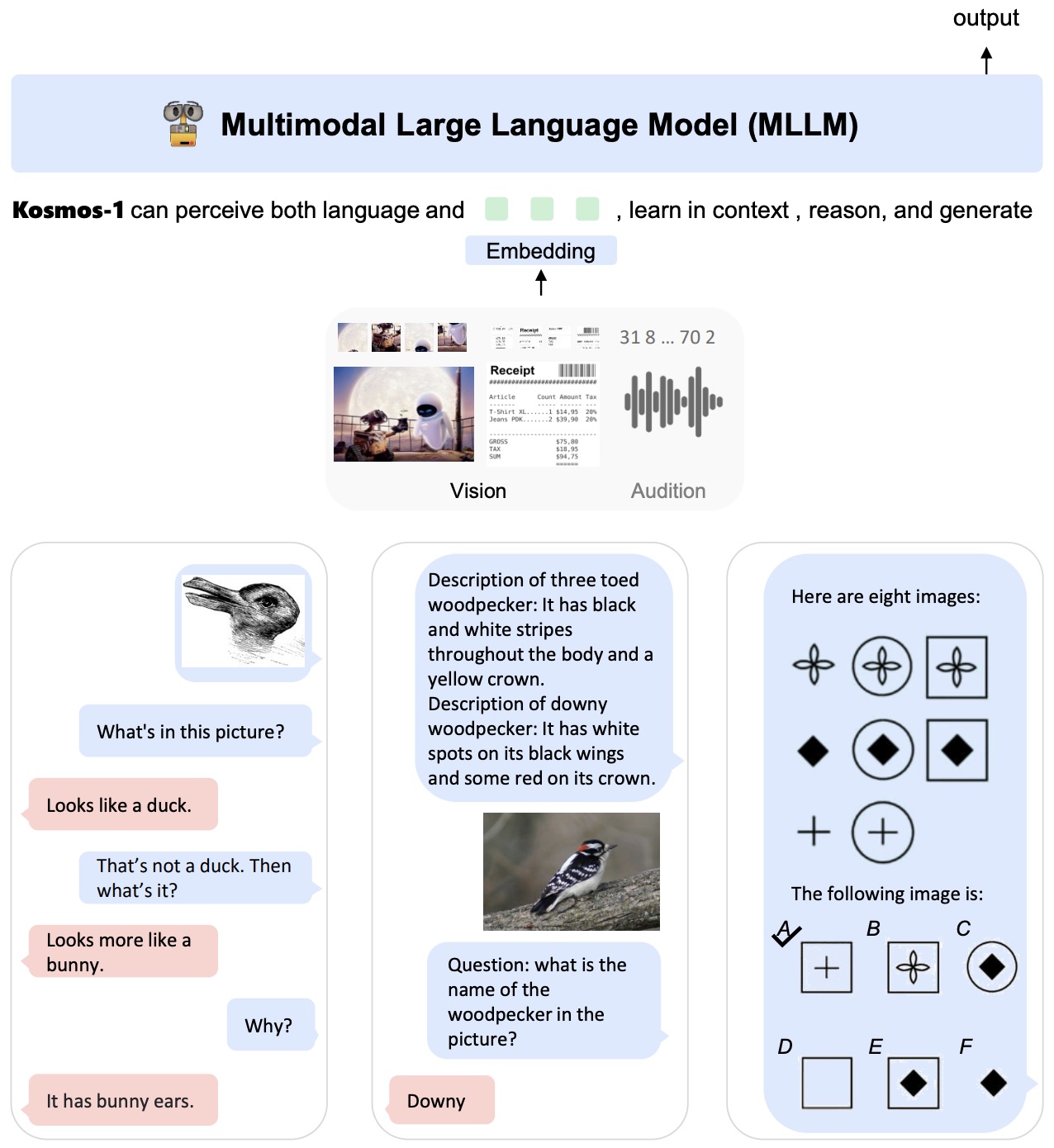

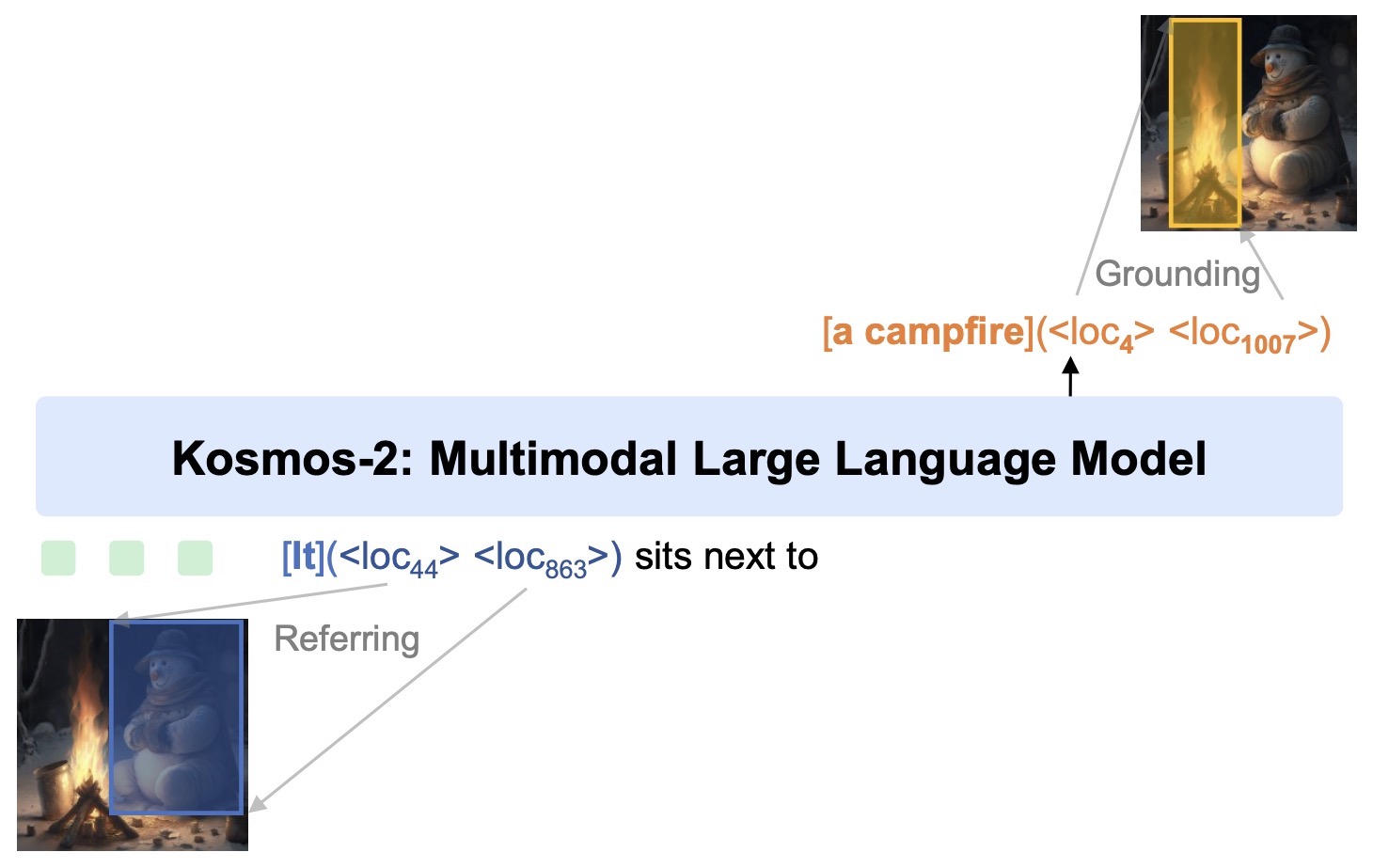

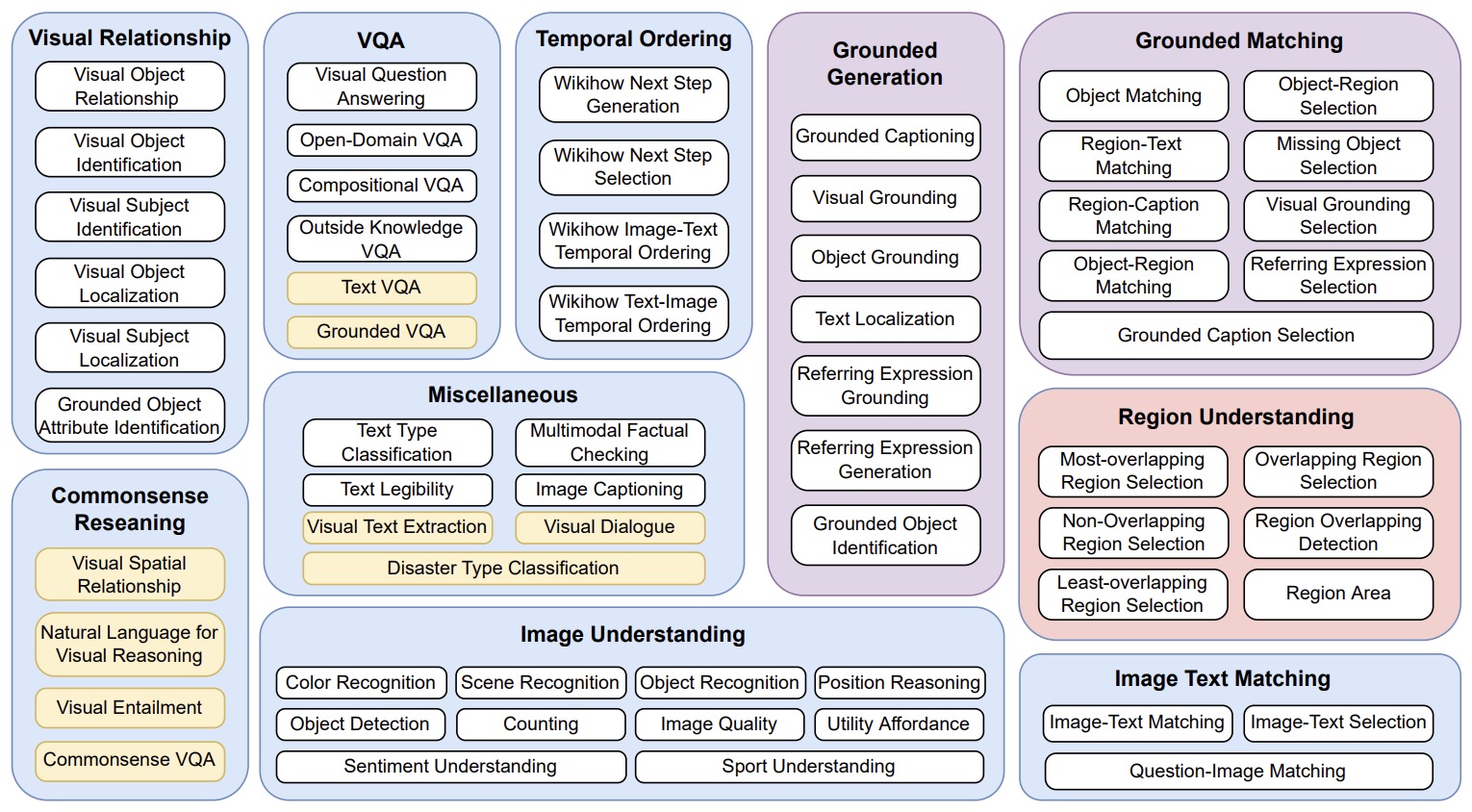

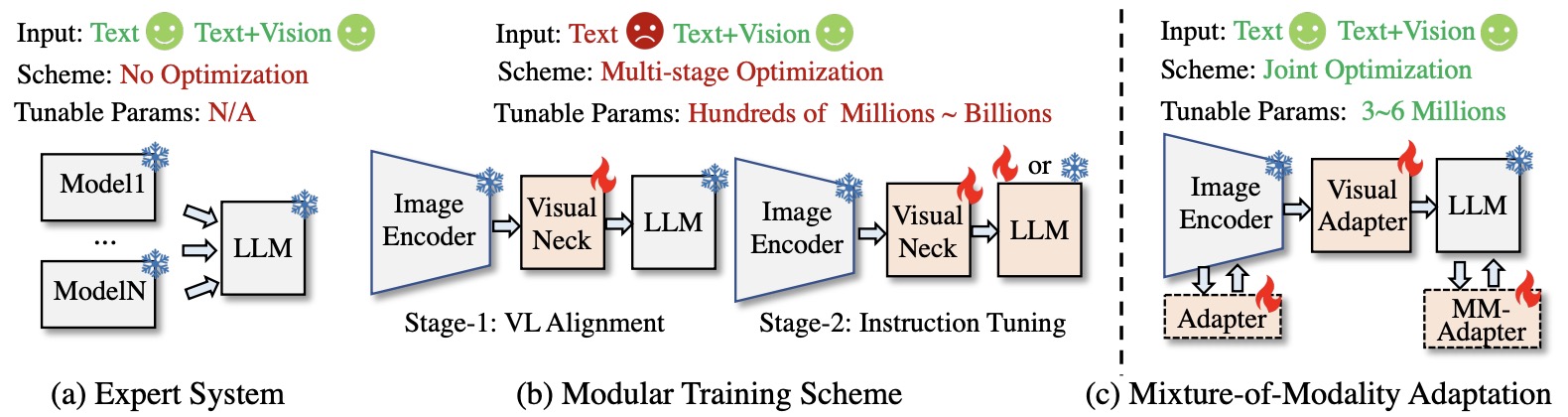

KOSMOS-1